Phineas T. Barnum

Phineas Taylor Barnum (July 5, 1810 – April 7, 1891) was an American showman who is best remembered for his entertaining hoaxes and for founding the circus that eventually became Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus.

Early Life

Barnum was born in Bethel, Connecticut, the son of inn-keeper and store-keeper Philo Barnum and third great grandson of Thomas Barnum, the immigrant ancestor of the Barnum family in North America. Barnum first started as a store-keeper, and was also involved with the lottery mania then prevailing in the United States. After failing in business, he started a weekly paper in 1829, The Herald of Freedom, in Danbury, Connecticut. After several libel suits and a prosecution which resulted in imprisonment, he moved to New York City in 1834. In 1835 began his career as a showman with his purchase and exhibition of a blind and almost completely paralyzed African-American slave woman, Joice Heth, claimed by Barnum to have been the nurse of George Washington, and to be over 160 years old.

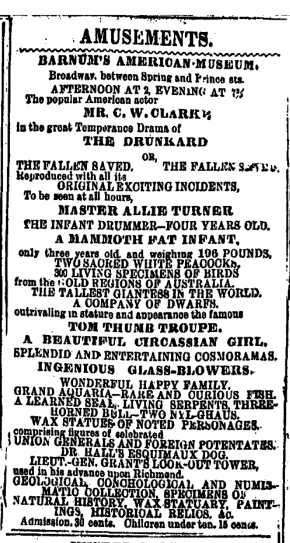

With this woman and a small company he made well-advertised and successful tours in America until 1839, though Joice Heth died in 1836, when her age was proved to be not more than eighty. After a period of failure he purchased Scudder's American Museum, at Broadway and Ann Street, New York City, in 1841. Renamed "Barnum's American Museum" with a considerable addition of exhibits, it became one of the most popular showplaces in the United States. He made a special hit in 1842 with the exhibition of Charles Stratton, the celebrated dwarf "General Tom Thumb," as well as the Feejee Mermaid which he exhibited in collaboration with his Boston counterpart Moses Kimball. His collection also included the original Siamese twins, Chang and Eng Bunker. In 1843 Barnum hired the traditional Native American dancer Do-Hum-Me. During 1844-45 Barnum toured with Charles Stratton in Europe and met with Queen Victoria. A remarkable instance of his enterprise was the engagement of Jenny Lind to sing in America at $1,000 USD a night for 150 nights, all expenses being paid by the entrepreneur. The tour began in 1850, and was a great success for both Lind and Barnum.

Barnum retired from the show business in 1855, but had to settle with his creditors in 1857, and began his old career again as showman and museum proprietor. In 1862 he discovered the giantess Anna Swan but on July 13, 1865, Barnum's American Museum burned to the ground. Barnum quickly reestablished the Museum at another location in New York City, but this too was destroyed by fire in March 1868. In Brooklyn, New York in 1871 with William Cameron Coup, he established "P. T. Barnum's Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome," a traveling amalgamation of circus, menagerie and museum of "freaks," which by 1872 was billing itself as "The Greatest Show on Earth." It went through a number of variants on these names: "P.T. Barnum's Travelling World's Fair, Great Roman Hippodrome and Greatest Show On Earth," and after an 1881 merger with James Bailey and James L. Hutchinson, "P.T. Barnum's Greatest Show On Earth, And The Great London Circus, Sanger's Royal British Menagerie and The Grand International Allied Shows United," soon shortened to "Barnum & London Circus." He and Bailey split up again in 1885, but came back together in 1888 with the "Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show On Earth," later "Barnum & Bailey Circus," which toured around the world. The show's primary attraction was Jumbo, an African elephant he purchased in 1882 from the London Zoo.

Barnum built four mansions in Bridgeport, Connecticut during his life: Iranistan, Lindencroft, Waldemere and Marina. Iranistan was the most notable: a fanciful and opulent Moorish Revival splendor designed by Leopold Eidlitz with domes, spires and lacy fretwork, inspired by the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, England. This mansion was built 1848 but burned down in 1857.[1]

Barnum died in his sleep at his Bridgeport home on April 7, 1891 and was buried in Mountain Grove Cemetery, Bridgeport, Connecticut. A statue in his honor was erected in 1893 at Seaside Park, by the water in Bridgeport. Barnum had donated the land for this park in 1865. His circus was eventually sold to Ringling Brothers on July 8, 1907 for a price of $400,000 USD. [2]

Author and debunker

Mass publication of his autobiography was one of Barnum's more successful methods of self-promotion. The autobiography was so popular that some people made a point of acquiring and reading each edition. Some collectors were known to boast they had a copy of every edition in their library. Barnum eventually gave up his claim of copyright to allow other printers to publish and sell inexpensive editions. At the end of the 19th century the number of copies printed of the autobiography was second only to the number of copies of the New Testament printed in North America.

Often referred to as the "Prince of Humbugs," Barnum saw nothing wrong in entertainers or vendors using hype (or "humbug," as he termed it) in their promotional material, just as long as the public was getting good value for its money. However, he was contemptuous of those who made money through fraudulent deceptions, especially the spiritualist mediums popular in his day. Prefiguring illusionists Harry Houdini and James Randi, Barnum publicly exposed "the tricks of the trade" used by mediums to deceive and cheat grieving survivors. In The Humbugs of the World, he offered a $500 reward to any medium who could prove their claimed power to communicate with the dead without trickery.

Politician and reformer

Barnum was significantly involved in the politics surrounding race, slavery, and sectionalism in the period leading up the American Civil War. As mentioned above, he had some of his first success as an impresario through his slave Joice Heth. Around 1850, he was involved in a hoax about a weed that would turn black people white.

Barnum was involved (both as performer and promoter) in blackface minstrelsy. According to Eric Lott, Barnum's minstrel shows were often more double-edged in their humor than most at this period. While still replete with racist stereotypes, Barnum's shows also satirized white racial attitudes, as in a stump speech in which a black phrenologist (like all performers in the show, actually a white man in blackface) made a dialect speech paralleling and parodying lectures given at the time to "prove" the superiority of the white race: "You see den, dat clebber man and dam rascal means de same in Dutch, when dey boph white; but when one white and de udder's black, dat's a grey hoss ob anoder color." [3]

Promotion of minstrel shows led indirectly to his sponsorship in 1853 of H.J. Conway's politically watered-down stage version of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin; the play, at Barnum's American Museum, gave the story a happy ending, with Tom and various other slaves freed. The success of this Uncle Tom led, in turn, to his promotion of a production of a play based on Stowe's Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. By 1860, Barnum had become a Republican.

While he claimed "politics were always distasteful to me," Barnum was elected to the Connecticut legislature in 1865 as the Republican representative for Fairfield and served two terms. In the debate over slavery and African-American suffrage with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Barnum spoke eloquently before the legislature and said, in part, "A human soul is not to be trifled with. It may inhabit the body of a Chinaman, a Turk, an Arab or a Hotentot - it is still an immortal spirit!" He ran for the United States Congress in 1867 and lost. In 1875, Barnum was elected mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut for a one year term and worked vigorously to improve the city water supply, bring gaslighting to the streets, and strictly enforce liquor and prostitution laws. Barnum was instrumental in starting Bridgeport Hospital, founded in 1878, and served as its first president. [4]

Works

- Art of Getting Money, or, Golden Rules for Making Money

- Struggles and Triumphs, or Forty Years' Recollections of P.T. Barnum

- The Colossal P.T. Barnum Reader: Nothing Else Like It in the Universe

- The Life of P.T. Barnum: Written By Himself

- The Wild Beasts, Birds and Reptiles of the World: The Story of their Capture

- The Humbugs of the World

Notes

- ↑ Barnum Museum Core Exhibits Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- ↑ Kunhardt, Philip B., Jr., Kunhardt, Philip B., III and Kunhardt, Peter W. P.T. Barnum: America's Greatest Showman. New York: Knopf, 1995. ISBN 9780679435747.

- ↑ Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0195078322.

- ↑ Kunhardt, Philip B., Jr.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Bluford. E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997. ISBN 9780816626311

- Barnum, Patrick Warren. Barnum genealogy 650 years of family history. Laredo, Tex: Ediciones InterGrafica 2005. ISBN 9780976872702

- Benton, Joel. The life of Phineas T. Barnum. [Ottawa]: eBooksLib 2004. ISBN 9781554493289

- Cook, James W. The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780674005914

- Harding, Les. Elephant Story: Jumbo and P. T. Barnum Under the Big Top. Jefferson, NC.: McFarland & Co., 2000. ISBN 0786406321

- Harris, Neil. Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973. ISBN 0226317528.

- Reiss, Benjamin. The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death, and Memory in Barnum's America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. ISBN 0674006364

- Saxon, Arthur H. P.T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995. ISBN 0231056877.

External links

- P.T. Barnum's genealogy Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- P.T. Barnum's gravesite Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- The Barnum Museum Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- P.T. Barnum at Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- Barnum's American Museum Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- The Lost Museum Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- The Life of Phineas T. Barnum Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- P.T. Barnum and Henry Bergh Retrieved October 16, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.