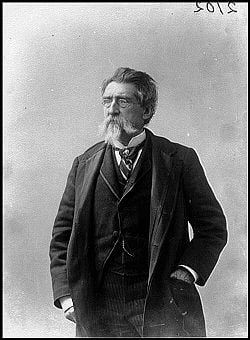

Mathew Brady

Mathew B. Brady (ca. 1823 - January 15, 1896), was a celebrated American photographer whose rise to prominence occurred largely in the years preceding and during the American Civil War. He is most known for having photographed that war. Following the conflict, a war weary public lost interest in seeing photos of the war, and Brady’s popularity and practice declined drastically, so much so that he went bankrupt and died in poverty in a charity ward.

War and combat photographs and photographers constitute one of the most important parts of all of photography, and Mathew Brady is remembered and praised for his pioneering role in creating this photographic tradition and niche.

Life and Early Work

Brady was born in Warren County, New York, to Irish immigrant parents, Andrew and Julia Brady. He moved to New York City at the age of 16 or 17. He first took a job as a department store clerk. Shortly after that he started his own small business manufacturing jewelry cases and in his spare time he studied photography. He had a number of photography teachers, including Samuel F. B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph and the person who had recently introduced photography to America. Brady quickly discovered a natural gift for photography and by 1844 he had his own photography studio in New York. By 1845 he began to exhibit his portraits of famous Americans. He opened a studio in Washington, D.C. in 1849, where he met Juliette Handy, whom he married in 1851.

Brady's early images were daguerreotypes, and he won many awards for his work. In the 1850s ambrotype photography became popular, which gave way to the albumen print, a paper photograph produced from large glass negatives. The albumen print process was the photographic process most commonly used in the American Civil War photography. In 1859, Parisian photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri popularized the carte de visite and these small pictures (the size of a visiting card) rapidly became a popular novelty as thousands of these images were created and sold in the United States and Europe. Brady's studio used all these techniques at varying times.

Photographing the American Civil War

The American Civil War was not the first to be photographed—that accolade is usually given to the Crimean War, which was photographed by Roger Fenton and others. Fenton spent three-and-a-half months in the Crimea, March 8 to June 26, 1855, and produced 360 photographs under extremely difficult conditions. Fenton's work gives a documentation of the participants and the landscape of the war, but Fenton's photographs contain no actual combat scenes and no scenes of the devastating effects of war.

Mathew Brady's efforts just over half a decade later to document the American Civil War earned Brady his place in history. He attempted to do this on a grand scale by bringing his photographic studio right onto the battlefields. Despite the obvious dangers, financial risk, and discouragement of his friends, he is later quoted as saying "I had to go. A spirit in my feet said 'Go,' and I went." Brady's photographs did show the horrors and devastation of war, and were probably the first to present war and its results in that full way. His first popular photographs of the conflict were at the First Battle of Bull Run, in which he got so close to the action that he only just avoided being captured.

In 1862, Brady presented an exhibition of photographs from the Battle of Antietam in his New York gallery entitled, "The Dead of Antietam." Many of the images in this presentation were graphic photographs of corpses, something that was then totally new to America. This was the first time that most people had seen the realities of war firsthand (albeit in photographs), as distinct from previous "artists' impressions" of war, impressions that were somewhat stylized and that lacked the immediacy and grittiness of photographs. The New York Times wrote that Brady's pictures had brought "home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war."

Brady did little of the actual photographing of the war himself. He employed numerous photographers: Alexander Gardner, James Gardner, Timothy H. O'Sullivan, William Pywell, George N. Barnard, Thomas C. Roche, and 17 other men. Each of them was given a traveling darkroom, to go out and photograph scenes from the Civil War. Brady rarely visited battlefields personally, generally staying in Washington, D.C. and organizing his assistants. This may have been due, at least in part, to the fact that his eyesight began to deteriorate in the 1850s.

During the war Brady spent over $100,000 to create 10,000 prints. He expected the U.S. government to buy the photographs when the war ended, but when the government refused to do so he was forced to sell his New York City studio and go into bankruptcy. Congress granted Brady $25,000 in 1875, but he remained deeply in debt. Depressed by his financial situation, and devastated by the death of his wife in 1887, Brady became an alcoholic and died penniless in the charity ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York City from complications following a streetcar accident. His funeral was financed by veterans of the 7th New York Infantry. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Levin Corbin Handy, Brady's nephew by marriage, took over his uncle's photography business after his death.

Mathew Brady's Legacy

Despite ultimate financial failure, Mathew Brady's effect on photography was great and lasting. His work demonstrated that photographs and photography can be more than posed portraits, and his Civil War pictures are the first example of comprehensive photo-documentation of a war. He was the forerunner of all the great war and combat photographers who came after him, especially those such as Robert Capa, Joe Rosenthal, Eddie Adams, David Douglas Duncan, W. Eugene Smith, Larry Burrows, and many others who—some at the cost of their lives—took the famous and stunning pictures of the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars, and the many other wars that have occurred since the American Civil War.

People Brady Photographed

Brady photographed portraits of many senior Union officers in the war, such as Ulysses S. Grant, Nathaniel Banks, Don Carlos Buell, Ambrose Burnside, Benjamin Butler, Joshua Chamberlain, George Custer, David Farragut, John Gibbon, Winfield Scott Hancock, Samuel P. Heintzelman, Joseph Hooker, Oliver Howard, David Hunter, John A. Logan, Irvin McDowell, George McClellan, James McPherson, George Meade, David Dixon Porter, William Rosecrans, John Schofield, William Sherman, Daniel Sickles, Henry Warner Slocum, George Stoneman, Edwin V. Sumner, George Thomas, Emory Upton, James Wadsworth, and Lew Wallace. On the Confederate side, Brady managed to photograph P.G.T. Beauregard, Stonewall Jackson, James Longstreet, Lord Lyons, James Henry Hammond, and Robert E. Lee. (Lee's first session with Brady was in 1845 as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, his final after the war in Richmond, Virginia.) Brady also photographed Abraham Lincoln on many occasions.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hobart, George. Mathew Brady. Masters of Photography, London: MacDonald, 1984. ISBN 0356105016

- Horan, James David, and Picture Collation by Gertrude Horan. Mathew Brady, Historian With a Camera. New York: Bonanza Books, 1955.

- Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve, and Philip B. Kunhardt, Jr., and the editors of Time-Life Books. Mathew Brady and His World: Produced by Time-Life Books From Pictures in the Meserve Collection. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books; Morristown, N.J.: School and Library Distribution by Silver Burdett Co., 1977.

- Meredith, Roy. Mathew Brady's Portrait of an Era. New York: Norton, 1982. ISBN 0393013952

- Panzer, Mary. Mathew Brady and the Image of History. Washington DC: Smithsonian Books, 1997. ISBN 1588341437

- Sullivan, George. Mathew Brady: His Life and Photographs. New York: Cobblehill Books, 1994. ISBN 0525651861

External links

All links retrieved November 7, 2022.

- Mathew Brady

- Mathew Brady in the Civil War

- Civil War Photographs by Mathew Brady and his collaborators Library of Congress

- Find-A-Grave profile for Matthew Brady

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.