Confederate States of America

| |||||

| Motto: Deo Vindice (Latin: With God As Our Vindicator) | |||||

| Anthem: God Save the South (unofficial) Dixie (popular) The Bonnie Blue Flag (popular) | |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Montgomery, Alabama (February 4, 1861–May 29, 1861) Richmond, Virginia (May 29, 1861–April 9, 1865) Danville, Virginia April 3–April 10, 1865) | ||||

| Largest city | New Orleans (February 4, 1861–May 1, 1862) (captured) Richmond April 3, 1865–surrender | ||||

| Official language | English de facto nationwide French and Native American languages regionally | ||||

| Government President Vice President |

Federal republic Jefferson Davis (D) Alexander Stephens (D) | ||||

| Area - Total - % water |

(excl. MO & KY) 1,995,392 km² 5.7% | ||||

| Population - 1860 Census - Density |

(excl. MO & KY) 9,103,332 (including 3,521,110 slaves) | ||||

Independence - Declared - Recognized - Recognition - Dissolution |

see Civil War February 4, 1861 by Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha on July 30, 1861 June 23, 1865 | ||||

| Currency | CSA dollar (only notes issued) | ||||

The Confederate States of America (a.k.a. the Confederacy, the Confederate States, or CSA) were the eleven southern states of the United States of America that seceded between 1861 and 1865. Seven states declared their independence from the United States before Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president; four more did so after the American Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter, when the CSA attacked the U.S. The United States ("The Union") held secession illegal and refused recognition of the Confederacy. Although no European powers officially recognized the CSA, British commercial interests sold it warships and operated blockade runners to help supply it.

When Robert E. Lee and the other generals surrendered their armies in the spring of 1865, the CSA collapsed, and there was no guerrilla warfare afterwards. A difficult, decade-long process of Reconstruction temporarily gave civil rights and the right to vote to the freedmen, and expelled ex-Confederate leaders from office, and permanently re-admitted the states to representation in Congress.

History

Secession process December 1860-May 1861

Seven states seceded by March 1861:

- South Carolina (December 20, 1860)

- Mississippi (January 9, 1861)

- Florida (January 10, 1861)

- Alabama (January 11, 1861)

- Georgia (January 19, 1861)

- Louisiana (January 26, 1861)

- Texas (February 1, 1861)

After Lincoln called for troops four more states seceded:

- Virginia (April 17, 1861)

- Arkansas (May 6, 1861)

- Tennessee (May 7, 1861)

- North Carolina (May 20, 1861)

Following Abraham Lincoln's election as President of the United States in 1860 on a platform that opposed the extension of slavery, seven slave-supporting southern states chose to secede from the United States and declared that the Confederate States of America was formed on February 4, 1861; Jefferson Davis was selected as its first President the next day.

Texas joined the Confederate States of America on March 2, and then replaced its governor, Sam Houston, when he refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederate States of America. These seven states seceded from the United States and took control of military/naval installations, ports, and custom houses within their boundaries, triggering the American Civil War.

A month after the Confederate States of America was formed, on March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President of the United States. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a "more perfect union" than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, that it was a binding contract, and called the secession "legally void." The legal issue of whether or not the Constitution was a binding contract has rarely been addressed by academics, and to this day is a hotly debated concept. He stated he had no intent to invade Southern states, but would use force to maintain possession of federal property and collection of various federal taxes, duties, and imposts. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union.

On April 12, South Carolina troops fired upon the federal troops stationed at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, until the troops surrendered. Following the Battle of Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for all remaining states in the Union to send troops to recapture Sumter and other forts, defend the capital (Washington, D.C.), and preserve the Union. Most Northerners believed that a quick victory for the Union would crush the rebellion, and so Lincoln only called for volunteers for 90 days of duty. Lincoln's call for troops resulted in four more states voting to secede. Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina joined the Confederacy for a total of eleven. Once Virginia joined the Confederate States, the Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, Virginia.

Kentucky was a border state during the American Civil War and, for a time, had two state governments, one supporting the Confederacy and one supporting the Union. The original government of Kentucky remained in the Union after a short-lived attempt at neutrality, but a rival faction from that state was accepted as a member of the Confederate States of America. A more complex situation surrounds the Missouri Secession, but, in any event, Missouri was also considered a member of the Confederate States of America. With Kentucky and Missouri, the number of Confederate states is thus sometimes considered to be thirteen.

The five tribal governments of the Indian Territory—which became Oklahoma in 1907—also mainly supported the Confederacy.

The southern part of New Mexico Territory (including parts of the Gadsden Purchase) joined with the Confederacy as Arizona Territory. Settlers there petitioned the Confederate government for annexation of their lands, prompting an expedition in which territory south of the 34th parallel (which roughly divides the current state in half) was governed by the Confederacy.

Preceding his New Mexico Campaign, General Sibley proclaimed to the people of New Mexico his intent to take possession of the territory in the name of the Confederate States of America. Confederate States troops briefly occupied the territorial capital of Santa Fe between March 13 and April 8, 1862. Arizona troops were also officially recognized within the armies of the Confederacy.

Not all jurisdictions where slavery was still legal joined the Confederate States of America. In 1861, martial law was declared in Maryland (the state which borders the U.S. capital, Washington, D.C., on three sides) to block attempts at secession. Delaware, also a slave state, never considered secession, nor did the capital of the U.S., Washington, D.C. In 1861, during the war, a unionist rump legislature in Wheeling, Virginia seceded from Virginia, claiming 48 counties, and joined the United States in 1863 as the state of West Virginia, with a constitution that would have gradually abolished slavery. Similar attempts to secede from the Confederate States of America in parts of other states (notably in eastern Tennessee) were held in check by Confederate declarations of martial law.

The surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia by General Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, is generally taken as the end of the Confederate States. President Davis was captured at Irwinville, Georgia on May 10, and the remaining Confederate armies surrendered by June 1865. The last Confederate flag was hauled down, on CSS Shenandoah, on November 6, 1865.

Government and politics

Constitution

The Confederate States Constitution provides much insight into the motivations for secession from the Union. Based to a certain extent on both the Articles of Confederation and on the United States Constitution, it reflected a stronger philosophy of states' rights, curtailing the power of the central authority, and also contained explicit protection of the institution of slavery, though international slave trading was prohibited. It differed from the U.S. Constitution chiefly by addressing the grievances of the secessionist states against the federal government of the United States. For example, the Confederate government was prohibited from instituting protective tariffs, making southern ports more attractive to international traders. Most southerners regarded protective tariffs as a measure that enriched the northern states at the expense of the South. The Confederate government was also prohibited from using revenues collected in one state for funding internal improvements in another state. One of the most notable differences in the Confederate Constitution is its reference to God. While the original United States Constitution acknowledged the people of the United States as the government's source of power, the Confederacy invoked the name of "Almighty God" as their source of legitimacy. At the same time, however, much of the Confederate constitution was a word-for-word duplicate of the U.S. one.

At the drafting of the Constitution of the Confederate States of America, a few radical proposals such as allowing only slave states to join and the reinstatement of the Atlantic slave trade were turned down. The Constitution specifically did not include a provision allowing states to secede, since the southerners considered this to be a right intrinsic to a sovereign state which the United States Constitution had not required them to renounce, and thus including it as such would have weakened their original argument for secession.

The President of the Confederate States of America was to be elected to a six-year term and could not be reelected. The only president was Jefferson Davis; the Confederate States of America was defeated by the federal government before he completed his term. One unique power granted to the Confederate president was the ability to subject a bill to a line item veto, a power held by some state governors. The Confederate Congress could overturn either the general or the line item vetoes with the same two thirds majorities that are required in the Congress of the United States.

Printed currency in the forms of bills and stamps was authorized and put into circulation, although by the individual states in the Confederacy's name. The government considered issuing Confederate coinage. Plans, dies, and four "proofs" were created, but a lack of bullion prevented any public coinage.

Although the preamble refers to "each State acting in its sovereign and independent character," it also refers to the formation of a "permanent federal government." Also, although slavery was protected in the constitution, it also prohibited the importation of new slaves from outside the Confederate States of America (except from slave holding states or territories of the United States).

Civil liberties

The Confederacy actively used the military to arrest people suspected of loyalty to the United States. They arrested at about the same rate as the Union. Neely found 2,700 names of men arrested and estimated the full list was much longer. Neely concludes, "The Confederate citizen was not any freer than the Union citizen—and perhaps no less likely to be arrested by military authorities. In fact, the Confederate citizen may have been in some ways less free than his Northern counterpart. For example, freedom to travel within the Confederate states was severely limited by a domestic passport system" (Neely 11, 16).

Capital

The capital of the Confederate States of America was Montgomery, Alabama from February 4, 1861 until May 29, 1861. Richmond, Virginia was named the new capital on May 6, 1861. Shortly before the end of the war, the Confederate government evacuated Richmond, planning to relocate further south. Little came of these plans before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House. Danville, Virginia served as the last capital of the Confederate States of America, from April 3 to April 10, 1865.

International diplomacy

Once the war with the United States began, the best hope for the survival of the Confederacy was military intervention by Britain and France. The U.S. realized that also and made it clear that recognition of the Confederacy meant war with the United States—and the cutoff of food shipments into Britain. The Confederates, who had believed that "cotton is king"—that is, Britain had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton—were proven wrong. Britain, in fact, had ample stores of cotton in 1861 and depended much more on grain from the Union states.

During its existence, the Confederate government sent repeated delegations to Europe. James M. Mason was sent to London as Confederate minister to Queen Victoria, and John Slidell was sent to Paris as minister to Napoleon III. Both were able to obtain private meetings with high British and French officials, but they failed to secure official recognition for the Confederacy. Britain and the United States were at sword's point during the Trent Affair in late 1861. Mason and Slidell had been illegally seized from a British ship by an American warship. Queen Victoria's husband, Prince Albert, helped calm the situation, and Lincoln released Mason and Slidell, so the episode was no help to the Confederacy.

Throughout the early years of the war, both British foreign secretary Lord Russell and Napoleon III, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, were interested in the idea of recognition of the Confederacy, or at least of offering a mediation. Recognition meant certain war with the United States, loss of American grain, loss of exports to the United States, loss of huge investments in American securities, possible war in Canada and other North American colonies, much higher taxes, many lives lost, and a severe threat to the entire British merchant marine, in exchange for the possibility of some cotton. Many party leaders and the general public wanted no war with such high costs and meager benefits. Recognition was considered following the Second Battle of Manassas when the British government was preparing to mediate in the conflict, but the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam and Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, combined with internal opposition, caused the government to back away.

In November 1863, Confederate diplomat A. Dudley Mann met Pope Pius IX and received a letter addressed "to the Illustrious and Honorable Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America." Mann, in his dispatch to Richmond, interpreted the letter as "a positive recognition of our Government," and some have mistakenly viewed it as a de facto recognition of the C.S.A. Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, however, interpreted it as "a mere inferential recognition, unconnected with political action or the regular establishment of diplomatic relations" and thus did not assign it the weight of formal recognition. For the remainder of the war, Confederate commissioners continued meeting with Cardinal Antonelli, the Vatican Secretary of State. In 1864, Catholic Bishop Patrick N. Lynch of Charleston traveled to the Vatican with an authorization from Jefferson Davis to represent the Confederacy before the Holy See.

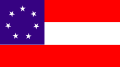

Confederate flags

The official flag of the Confederate States of America, and the one actually called the "Stars and Bars," has seven stars, for the seven states that initially formed the Confederacy. This flag was sometimes hard to distinguish from the Union flag under battle conditions, so the Confederate battle flag, the "Southern Cross," became the one more commonly used in military operations. The Southern Cross has 13 stars, adding the four states that joined the Confederacy after Fort Sumter, and the two divided states of Kentucky and Missouri.

As a result of its depiction in twentieth century popular media, the "Southern Cross" is a flag commonly associated with the Confederacy today. The actual "Southern Cross" is a square-shaped flag, but the more commonly seen rectangular flag is actually the flag of the First Tennessee Army, also known as the Naval Jack because it was first used by the Confederate Navy.

The Confederate battle flag is a controversial symbol in contemporary American politics. Many Americans, particularly African Americans, consider it a racist symbol akin to the Nazi swastika because of its link to the slavery in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, Southern opponents of the Civil Rights Movement, the Klu Klux Klan, American neo-Nazis, and other white supremacists have used the flag as a symbol for their causes. Many southerners, however, see the flag as a symbol of Southern pride and culture. As a result, there have been numerous political fights over the use of the Confederate battle flag in Southern state flags, at sporting events at Southern universities, and on public buildings.

Political leaders of the Confederacy

Executive

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Jefferson Davis | 25 February 1861–(10 May)1865 |

| Vice President | Alexander Stephens | 25 February 1861–(11 May)1865 |

| Secretary of State | Robert Toombs | 25 February 1861–25 July 1861 |

| Robert M. T. Hunter | 25 July 1861–22 February 1862 | |

| William M. Browne (acting) | 7 March 1862–18 March 1862 | |

| Judah P. Benjamin | 18 March 1862–May 1865 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Christopher Memminger | 25 February 1861–15 June 1864 |

| George Trenholm | 18 July 1864–27 April 1865 | |

| John H. Reagan | 27 April 1865–(10 May)1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Leroy Pope Walker | 25 February 1861–16 September 1861 |

| Judah P. Benjamin | 17 September 1861–24 March 1862 | |

| George W. Randolph | 24 March 1862–15 November 1862 | |

| Gustavus Smith (acting) | 17 November 1862–20 November 1862 | |

| James Seddon | 21 November 1862– 5 February 1865 | |

| John C. Breckinridge | 6 February 1865–May 1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Stephen Mallory | 4 March 1861–(20 May)1865 |

| Postmaster General | John H. Reagan | 6 March 1861–(10 May)1865 |

| Attorney General | Judah P. Benjamin | 25 February 1861–17 September 1861 |

| Wade Keyes (acting) | 17 September 1861–21 November 1861 | |

| Thomas Bragg | 21 November 1861–18 March 1862 | |

| Thomas H. Watts | 18 March 1862– 1 October 1863 | |

| Wade Keyes (acting 2nd time) | 1 October 1863–4 January 1864 | |

| George Davis | 4 January 1864–24 April 1865 | |

Legislative

The legislative branch of the Confederate States of America was the Confederate Congress. Like the United States Congress, the Confederate Congress consisted of two houses: The Confederate Senate, whose membership included two senators from each state (and chosen by the state legislature), and the Confederate House of Representatives, with members popularly elected by residents of the individual states. Speakers of the Provisional Congress

- Robert Woodward Barnwell of South Carolina—February 4, 1861

- Howell Cobb, Sr. of Georgia—February 4, 1861-February 17, 1862

- Thomas Stanhope Bocock of Virginia—February 18, 1862-March 18, 1865

Presidents pro tempore

- Howell Cobb, Sr. of Georgia

- Robert Woodward Barnwell of South Carolina

- Josiah Abigail Patterson Campbell of Mississippi

- Thomas Stanhope Bocock of Virginia

Tribal Representatives to Confederate Congress

- Elias Cornelius Boudinot 1862-65—Cherokee

- Burton Allen Holder 1864-1865—Chickasaw

- Robert McDonald Jones 1863-65—Choctaw

Sessions of the Confederate Congress

- Provisional Confederate Congress

- First Confederate Congress

- Second Confederate Congress

Judicial

A Judicial branch of the government was outlined in the C.S. Constitution but the would-be "Supreme Court of the Confederate States" was never created or seated because of the ongoing war. Some Confederate district courts were, however, established within some of the individual states of the Confederate States of America; namely, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia (and possibly others). At the end of the war, U.S. district courts resumed jurisdiction.

The state and local courts generally continued to operate as they had been, simply recognizing the CSA, rather than the USA, as the national government. Supreme Court—not established

District Court

- Asa Biggs 1861-1865

- John White Brockenbrough 1861

- Alexander Mosby Clayton 1861

- Jesse J. Finley 1861-1862

Geography

The Confederate States of America had a total of 2,919 miles (4,698 kilometers) of coastline. A large portion of its territory lay on the sea coast, and with level and sandy ground. The interior portions were hilly and mountainous and the far western territories were deserts. The lower reaches of the Mississippi River bisected the country, with the western half often referred to as the Trans-Mississippi. The highest point (excluding Arizona and New Mexico) was Guadalupe Peak in Texas at 8,750 feet (2,667 meters).

Subtropical climate

Most of the area of the Confederate States of America had a humid subtropical climate with mild winters and long, hot, humid summers. The climate varied to semiarid steppe and arid desert west of longitude 96 degrees west. The subtropical climate made winters mild, but allowed infectious diseases to flourish. They killed more soldiers than combat did.

River system

In peacetime the vast system of navigable rivers was a major advantage, allowing for cheap and easy transportation of farm products. The railroad system was built as a supplement, tying plantation areas to the nearest river or seaport. The vast geography made for difficult Union logistics and large numbers of soldiers to garrison captured areas and protect rail lines. But the Union navy seized most of the navigable rivers by 1862, making its logistics easy and Confederate movements very difficult. After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, it became impossible for units to cross the Mississippi as Union gunboats constantly patrolled. The South thus lost use of its western regions.

Rail network

The rail network was built for short hauls, not the long-distance movement of soldiers or goods, which was to be its role in the war. Some idea of the severe internal logistics problems the Confederacy faced can be seen by tracing Jefferson Davis's journey from Mississippi to neighboring Alabama when he was chosen president in early 1861. From his plantation on the river he took a steamboat down the Mississippi to Vicksburg, boarded a train to Jackson, where he took another train north to Grand Junction, Tennessee, then a third train east to Chattanooga, Tennessee, and a fourth train south to Atlanta, Georgia. Yet another train took Davis south to the Alabama border, where a final train took him west to Montgomery, his temporary national capital. As the war proceeded the Federals seized the Mississippi, burned trestles and railroad bridges, and tore up track; the frail Confederate railroad system faltered and virtually collapsed for want of repairs and replacement parts. In May 1861, the Confederate government abandoned Montgomery before the sickly season began, and relocated in Richmond, Virginia.

Rural nation

The Confederate States of America were not urbanized. The typical county seat had a population of less than a thousand, and cities were rare. Only New Orleans was in the list of top 10 U.S. cities in the 1860 census. Only 15 southern cities ranked among the top 100 U.S. cities in 1860, most of them were ports whose economic activities were shut down by the Union blockade. The population of Richmond swelled after it became the national capital, reaching an estimated 128,000 in 1864.

| # | City | 1860 Population | US Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | New Orleans, Louisiana | 168,675 | 6 |

| 2. | Charleston, South Carolina | 40,522 | 22 |

| 3. | Richmond, Virginia | 37,910 | 25 |

| 4. | Mobile, Alabama | 29,258 | 27 |

| 5. | Memphis, Tennessee | 22,623 | 38 |

| 6. | Savannah, Georgia | 22,292 | 41 |

| 7. | Petersburg, Virginia | 18,266 | 50 |

| 8. | Nashville, Tennessee | 16,988 | 54 |

| 9. | Norfolk, Virginia | 14,620 | 61 |

| 10. | Wheeling, Virginia | 14,083 | 63 |

| 11. | Alexandria, Virginia | 12,652 | 74 |

| 12. | Augusta, Georgia | 12,493 | 77 |

| 13. | Columbus, Georgia | 9,621 | 97 |

| 14. | Atlanta, Georgia | 9,554 | 99 |

| 15. | Wilmington, North Carolina | 9,553 | 100 |

Economy

The Confederacy had an agrarian-based economy that relied heavily on slave-run plantations with exports to a world market of cotton, and to a lesser extent tobacco and sugar cane. Local food production included grains, hogs, cattle, and gardens. The eleven states produced only $155 million in manufactured goods in 1860, chiefly from local grist mills, together with lumber, processed tobacco, cotton goods, and naval stores such as turpentine. The CSA adopted a low tariff of 10 percent, but imposed them on all imports from the United States. The tariff mattered little; the Confederacy's ports were shut to all commercial traffic by the Union blockade, and very few people paid taxes on goods smuggled from the U.S. The lack of adequate financial resources led the Confederacy to finance the war through printing money, which in turn led to high inflation.

Armed forces

The military armed forces of the Confederacy comprised the following three branches:

- Confederate States Army

- Confederate States Navy

- Confederate States Marine Corps

The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and U.S. Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and had been appointed to senior positions in the Confederate armed forces. Many had served in the Mexican War (such as Jefferson Davis), but others had little or no military experience (such as Leonidas Polk, who attended West Point but did not graduate). The Confederate officer corps was composed in part of young men from slave-owning families, but many came from non-owners. The Confederacy appointed junior and field grade officers by election from the enlisted ranks. Although no Army service academy was established for the Confederacy, many colleges of the south (such as the The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute) maintained cadet corps that were seen as a training ground for Confederate military leadership. A naval academy was established in 1863, but no midshipmen had graduated by the time the Confederacy collapsed.

The rank and file of the Confederate armed forces consisted of white males with an average age between 16 and 28. The Confederacy adopted conscription in 1862, but opposition was widespread. Depleted by casualties and desertions, the military suffered chronic manpower shortages. Towards the end of the Civil War, boys as young as 12 were fighting in combat roles and the Confederacy began an all-black regiment with measures underway to offer freedom to slaves who voluntarily served in the Confederate military.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Rable, George C. The Confederate Republic: A Revolution against Politics. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0807821442

- Roland, Charles Pierce. The improbable era: the South since World War II. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky 1975. ISBN 978-0813113357

- Thomas, Emory M. Confederate Nation: 1861-1865. New York: Harper & Row, 1979. ISBN 978-0060142520

- Wakelyn, Jon L. Biographical Dictionary of the Confederacy. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0837161242

- Warner, Ezra J., and W. Buck Yearns. Biographical register of the Confederate Congress. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press 1975. ISBN 978-0807100929

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.