Paiute

Paiute (sometimes written Piute) refers to two related groups of Native Americans — the Northern Paiute of California, Nevada and Oregon, and the Southern Paiute of Arizona, southeastern California, and Nevada, and Utah. The Northern and Southern Paiute both spoke languages belonging to the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan family of Native American languages.

Identity

The origin of the word Paiute is unclear. Some anthropologists have interpreted it as "Water Ute" or "True Ute." The Northern Paiute call themselves Numa (sometimes written Numu) ; the Southern Paiute call themselves Nuwuvi. Both terms mean "the people." The Northern Paiute are sometimes referred to as Paviotso. Early Spanish explorers called the Southern Paiute "Payuchi" (they did not make contact with the Northern Paiute). Early Euro-American settlers often called both groups of Paiute "Diggers" (presumably due to their practice of digging for roots), although that term is now considered derogatory.

The use of the name "Paiute" for these peoples is somewhat misleading. The Northern Paiute are more closely related to the Shoshone than to the Southern Paiute, while the Southern Paiute are more closely related to the Ute than to the Northern Paiute. Usage of the terms Paiute, Northern Paiute and Southern Paiute is most correct when referring to groups of people with similar language and culture, and should not be taken to imply a political connection or even an especially close genetic relationship. The Northern Paiute speak the Northern Paiute language, while the Southern Paiute speak the Ute-Southern Paiute language. These languages are not as closely related to each other as they are to other Numic languages.

The Bannock, Mono, Panamint and Kawaiisu people, who also speak Numic languages and live in adjacent areas, are sometimes referred to as Paiute.

History

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber thought that the 1770 population of the Northern Paiute within California was 500.

Northern Paiute

The Northern Paiute traditionally lived in the Great Basin in eastern California, western Nevada, and southeast Oregon. The Northern Paiute's pre-contact lifestyle was well adapted to the harsh desert environment in which they lived. Each tribe or band occupied a specific territory, generally centered on a lake or wetland that supplied fish and water-fowl. Rabbits and pronghorn were taken from surrounding areas in communal drives, which often involved neighboring bands. Individuals and families appear to have moved freely between bands. Pinyon nuts gathered in the mountains in the fall provided critical winter food. Grass seeds and roots were also important parts of their diet. The name of each band came from a characteristic food source. For example, the people at Pyramid Lake were known as the Cui Ui Ticutta (meaning "Cui-ui eaters"), the people of the Lovelock area were known as the Koop Ticutta (meaning "ground-squirrel eaters") and the people of the Carson Sink were known as the Toi Ticutta (meaning "tule eaters."

Relations among the Northern Paiute bands and their Shoshone neighbors were generally peaceful. In fact, there is no sharp distinction between the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone. Relations with the Washoe people, who were culturally and linguistically very different, were not so peaceful.

Sustained contact between the Northern Paiute and Euro-Americans came in the early 1840s, although the first contact may have occurred as early as the 1820s. Although they had already started using horses, their culture was otherwise largely unaffected by European influences at that point. The Pah Ute War, also known as the Paiute War, was a minor series of raids and ambushes initiated by the Paiute, which also had an adverse effect on the development of the Pony Express. It took place from May through June of 1860, though sporadic violence continued for a period afterwards.

Catherine S. Fowler and Sven Liljeblad put the total Northern Paiute population in 1859 at about 6,000As Euro-American settlement of the area progressed, several violent incidents occurred, including the Pyramid Lake War of 1860 and the Bannock War of 1878. These incidents took the general pattern of a settler steals from, rapes or murders a Paiute, a group of Paiutes retaliate, and a group of settlers or the US Army counter-retaliates. Many more Paiutes died from introduced diseases such as small pox. Sarah Winnemucca's book "Life Among the Piutes" gives a first-hand account of this period, although it is not considered to be wholly reliable.

The first reservation established for the Northern Paiute was the Malheur Reservation in Oregon. The federal government's intention was to concentrate the Northern Paiute there, but its strategy didn't work. Due to the distance of that reservation from the traditional areas of most of the bands, and due to the poor conditions on that reservation, many Northern Paiute refused to go there and those that did soon left. Instead they clung to the traditional lifestyle as long as possible, and when environmental degradation made that impossible, they sought jobs on white farms, ranches or cities and established small Indian colonies, where they were joined by many Shoshone and, in the Reno area, Washoe people. Later, large reservations were created at Pyramid Lake and Duck Valley, but by that time the pattern of small de facto reservations near cities or farm districts often with mixed Northern Paiute and Shoshone populations had been established. Starting in the early 1900s the federal government began granting land to these colonies, and under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 these colonies gained recognition as independent tribes. Kroeber estimated the population of the Northern Paiute in California in 1910 as 300.

Southern Paiute

The Southern Paiute traditionally lived in the Colorado River basin and Mojave Desert in northern Arizona, southeastern California, southern Nevada, and southern Utah.

First European contact with the Southern Paiutes occurred in 1776 when Fathers Silvestre Vélez de Escalante and Francisco Atanasio Domínguez chanced upon them during their failed attempt to find an overland route to the missions of California. Even before this date, the Southern Paiute suffered from slave raids by the Navajo and the Utes, but the introduction of Spanish and later Euroamerican explorers into their territory exacerbated the practice. In 1851, Mormon settlers strategically occupied Paiute water sources, which created a dependency relationship. However, the Mormon presence soon ended the slave raids, and relations between the Paiutes and the Mormons were basically peaceful. This was in large part due to the diplomacy efforts of Mormon missionary Jacob Hamblin. But there is no doubt that the introduction of European settlers and agricultural practices (most especially large herds of cattle) made it difficult for the Southern Paiutes to continue their traditional lifestyle.

The Utah Paiutes were terminated in 1954 from the list of Indian tribes formally recognized by the American government, but the Paiute people regained federal recognition in 1980. A band of Southern Paiutes at Willow Springs and Navajo Mountain, south of the Grand Canyon, reside inside the Navajo Indian Reservation. These "San Juan" Paiutes were recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1980.

Culture

The Paiute, like other tribes of the Great Basin area, lived in domed, round shelters known as Wickiups or Kahn by the Kaibab Paiute. The curved surfaces made them ideal shelters for all kinds of conditions; an escape from the sun during summer, and when lined with bark they were as safe and warm as the best houses of early colonists in winter. The structures were formed with a frame of arched poles, most often wooden, which are covered with some sort of roofing material. Details of construction varied with the local availability of materials, but generally included grass, brush, bark, rushes, mats, reeds, hides, or cloth. They built these dwellings in different locations as they moved throughout their territory. Since all their daily activities took place outside, including making fires for cooking or warmth, the shelters were primarily used for sleeping.

Ghost Dance

The Northern Paiutes living in Mason Valley, Nevada thrived on a subsistence pattern of foraging for cyperus bulbs for part of the year and augmenting their diets with fish, pine nuts, and occasionally wild game killed by clubbing it. Their social system had little hierarchy and relied instead on shamans who as self-proclaimed spiritually-blessed individuals organized events for the group as a whole. Usually, community events centered on the observance of a ritual at prescribed times of year, such as harvests or hunting parties.

A devastating typhoid epidemic struck in 1867. This, and other European diseases, killed approximately one-tenth of the total population, resulting in widespread psychological and emotional trauma, which brought grave disorder to the economic system preventing many families from continuing their nomadic lifestyle.

An extraordinary instance occurred in 1869 when the shaman Wodziwob organized a series of community dances to announce his vision. He spoke of a journey to the land of the dead and of promises made to him by the souls of the recently deceased. They promised to return to their loved ones within a period of three to four years. Wodziwob’s peers accepted this vision, probably due to his already-reputable status as a healer, as he urged his people to dance the common circle dance as was customary during a time of festival. He continued preaching this message for three years with the help of a local "weather doctor" named Tavibo, the father of Wovoka.

Wovoka was believed to have experienced a vision during a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. Wovoka had received training from an experienced shaman under his parents' guidance after they realized that he was having difficulty interpreting his previous visions. He was also in training to be a "weather doctor," following in his father’s footsteps, and was known in Mason Valley as a gifted young leader. He often presided over circle dances, while preaching a message of universal love. In addition, he had reportedly been influenced by the Christian teaching of Presbyterians for whom he had worked as a ranch hand, by local Mormons, and by the Indian Shaker Church. He also adopted the Anglo name, Jack Wilson.

According the report of Anthropologist James Mooney, who conducted an interview with Wilson in 1892, Wilson had stood before God in Heaven, and had seen many of his ancestors engaged in their favorite pastimes. God showed Wilson a beautiful land filled with wild game, and instructed him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God also stated that Wilson's people must work, not steal or lie, and that they must not engage in the old practices of war or the self-mutilation traditions connected with mourning the dead. God said that if his people kept by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in the other world.

According to Wilson, he was then given the formula for the proper conduct of the Ghost Dance and commanded to bring it back to his people. Wilson preached that if this five-day dance was performed in the proper intervals, the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. Wilson claimed to have left the presence of God convinced that if every Indian in the West danced the new dance to “hasten the event,” all evil in the world would be swept away leaving a renewed Earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethren, the new religion was termed “Dance In A Circle." Because the first Anglo contact with the practice came by way of the Sioux, their expression "Spirit Dance" was adopted as a descriptive title for all such practices. This was subsequently translated as "Ghost Dance."

Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As it spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself.

The Ghost Dance took on a more militant character among the Lakota Sioux who were suffering under the disastrous US government policy that had sub-divided their original reservation land and forced them to turn to agriculture. By performing the Ghost Dance, the Lakota believed they could take on a "Ghost Shirt" capable of repelling the white man's bullets. Another Lakota interpretation of Wovoka's religion is drawn from the idea of a "renewed Earth," in which "all evil is washed away." This Lakota interpretation included the removal of all Anglo Americans from their lands, unlike Wovoka's version of the Ghost Dance, which encouraged co-existence with Anglos. Seeing the Ghost Dance as a threat and seeking to suppress it, U.S. Government Indian agents initiated actions that tragically culminated with the death of Sitting Bull and the later Wounded Knee massacre.

After that tragedy, the Ghost Dance and its ideals as taught by Wokova soon began to lose energy and it faded from the scene, although some tribes still practiced into the twentieth century.

Contemporary

Southern Paiute communities are located at Las Vegas, Pahrump, and Moapa, in Nevada; Cedar City, Kanosh, Koosharem, Shivwits, and Indian Peaks, in Utah; at Kaibab and Willow Springs, in Arizona; Death Valley and at the Chemehuevi Indian Reservation and on the Colorado River Indian Reservation in California. Some would include the 29 Palms Reservation in Riverside County, California.

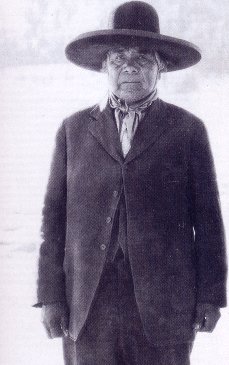

Famous Pauite

- Poito (Chief Winnemucca)

- Sarah Winnemucca

- Wovoka (Jack Wilson), founder of the Ghost Dance movement

- Chief Tenaya Leader of the Ahwahnees

- Numaga

- Ochio

- Truckee

- Captain John - Shibana or Poko Tucket

- Joaquin

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fowler, Catherine S. and Sven Liljeblad. 1978. "Northern Paiute." In Great Basin, edited by Warren L. d'Azevedo, pp. 435-465. Handbook of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant (ed.), vol. 11. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Grahame, John D. and Thomas D. Sisk, (eds.) 2002. Southern Paiute in Canyons, Cultures and Environmental Change: An Introduction to the Land-use History of the Colorado Plateau. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- Holt, Ronald L. Paiute Indians Utah History Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- Hopkins, Sarah Winnemucca. 1994. Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0874172522

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- Mooney, James. 1991. The Ghost-Dance Religion and Wounded Knee. Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486267593

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

- Burns Paiute Tribe

- Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe

- Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. Full text online.

- Paiute ~ Wovoka ~ Ghost Dancers Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- Pipe Spring National Monument Retrieved December 7, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.