Nez Perce

| Nez Perce |

|---|

| Total population |

| 3,499[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Languages |

| English, Nez Perce |

| Religions |

| Seven Drum (Walasat), Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Sahaptin peoples |

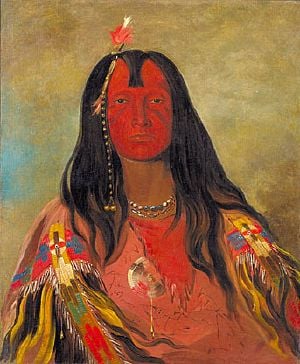

The Nez Perce (autonym: Niimíipu) are Native American people who live in the Pacific Northwest region (Columbia River Plateau) of the United States. An anthropological interpretation says they descended from the Old Cordilleran Culture, which moved south from the Rocky Mountains and west in Nez Perce lands.[2] The Nez Perce Nation currently governs and inhabits within the exterior boundaries of the reservation in Idaho.[3] The Nez Perce's name for themselves is Nimíipuu, meaning, "The People."[4]

They speak the Nez Perce language or Niimiipuutímt, a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin. The Sahaptian sub-family is one of the branches of the Plateau Penutian family (which in turn may be related to a larger Penutian grouping).

Name

Nez Percé is an exonym given by French Canadian fur traders who visited the area regularly in the late 18th century, meaning literally "pierced nose." The most common self-designation used today by the Nez Perce is Niimíipu.[4] "Nez Perce" is also used by the tribe itself, the United States Government, and contemporary historians. Older historical ethnological works use the French spelling "Nez Percé," with the diacritic. The original French pronunciation is Template:IPAc-fr, with three syllables.

In the journals of William Clark, the people are referred to as Chopunnish {{#invoke:IPAc-en|main}}{{#invoke:IPAc-en|main}}{{#invoke:IPAc-en|main}}/pənɪʃ/. This term is an adaptation of the term cú·pʼnitpeľu (the Nez Perce people) which is formed from cú·pʼnit (piercing with a pointed object) and peľu (people).[5] When analyzed through the Nez Perce Language Dictionary, the term cúpnitpelu contains no reference to "Piercing with a pointed object" as described by D.E. Walker. The prefix cú- means "in single file." This prefix, combined with the verb -piní, "to come out (e.g. of forest, bushes, ice)." Finally, with the suffix of -pelú, meaning "people or inhabitants of." Put all three parts of the Nez Perce word together now to get cú- + -piní + pelú = cúpnitpelu, or the People Walking Single File Out of the Forest.[6] Nez Perce oral tradition indicates the name "Cuupn'itpel'uu" meant "we walked out of the woods or walked out of the mountains" and referred to the time before the Nez Perce had horses.[7] Nez Perce is a misnomer given by the interpreter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition at the time they first encountered the Nez Perce in 1805. It is from the French, "pierced nose." This is an inaccurate description of the tribe. They did not practice nose piercing or wearing ornaments. The actual "pierced nose" tribe lived on and around the lower Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest and are commonly called the Chinook tribe by historians and anthropologists. The Chinook relied heavily upon salmon as did the Nez Perce and shared fishing and trading sites but were much more hierarchical in their social arrangements.

Traditional lands and culture

The Nez Perce area at the time of Lewis and Clark was approximately 17,000,000 acres (69,000 km²). It covered parts of Washington, Oregon, Montana, and Idaho, in an area surrounding the Snake, Salmon and the Clearwater rivers. The tribal area extended from the Bitterroots in the east to the Blue Mountains in the west between latitudes 45°N and 47°N.[8]

In 1800, there were more than 70 permanent villages ranging from 30 to 200 individuals, depending on the season and social grouping. About 300 total sites have been identified, including both camps and villages. In 1805 the Nez Perce were the largest tribe on the Columbia River Plateau, with a population of about 6,000. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Nez Perce had declined to about 1,800 because of epidemics, conflicts with non-Indians, and other factors.[9]

The Nez Perce, as many western Native American tribes, were migratory and would travel in seasonal rounds, according to where the abundant food was to be found at a given time of year. This migration followed a predictable pattern from permanent winter villages through several temporary camps, nearly always returning to the same locations year after year. They were known to go as far east as the Great Plains of Montana to hunt buffalo, and as far west as the west coast. In their travels Celilo Falls was a respected and favored location to fish for salmon on the Columbia River. They relied heavily on q'emes or camas gathered in the region between the Salmon and Clearwater River drainages as a food source.

The Nez Perce believed in spirits called weyekins (Wie-a-kins) which would, they thought, offer "a link to the invisible world of spiritual power".[10] The weyekin would protect one from harm and become a personal guardian spirit. To receive a weyekin, a young girl or boy age 12 to 15 would go to the mountains on a vision quest. The person on quest would carry no weapons, eat no food, and drink very little water. There, he or she would receive a vision of a spirit that would take the form of a mammal or bird. This vision could appear physically or in a dream or trance. The weyekin was to bestow the animal's powers on its bearer—for example; a deer might give its bearer swiftness. A person's weyekin was very personal. It was rarely shared with anyone and was contemplated in private. The weyekin stayed with the person until death.

The Nez Perce National Historical Park includes a research center which has the park's historical archives and library collection. It is available for on-site use in the study and interpretation of Nez Perce history and culture.[11]

History

First contact

William Clark was the first American to meet any of the tribe. While he, Meriwether Lewis and their men were crossing the Bitterroot Mountains they ran low of food, and Clark took six hunters and hurried ahead to hunt. On September 20, 1805, near the western end of the Lolo Trail, he found a small camp at the edge of the camas-digging ground that is now called Weippe Prairie. The explorers were favorably impressed by those whom they met; and, as they made the remainder of their journey to the Pacific in boats, they entrusted the keeping of their horses to "2 brothers and one son of one of the Chiefs." One of these Indians was Walammottinin (Hair Bunched and tied, but more commonly known as Twisted Hair), who became the father of Timothy, a prominent member of the "Treaty" faction in 1877. The Indians were, generally, faithful to the trust; and the party recovered their horses without serious difficulty when they returned.[12]

Flight of the Nez Perce

The Nez Perce split into two groups in the mid-19th century, with one side accepting coerced relocation to a reservation and the other refusing to give up their fertile land in Washington and Oregon. The flight of the non-treaty Nez Perce began on June 15, 1877, with Chief Joseph, Looking Glass, White Bird, Ollokot, Lean Elk (Poker Joe) and Toohoolhoolzote leading 800 men, women and children in an attempt to reach a peaceful sanctuary. They originally intended to seek shelter with their allies the Crow but upon the Crow's refusal to offer help they attempted to reach the camp of Lakota Chief Sitting Bull, who had fled to Canada.

The Nez Perce were pursued by over 2,000 soldiers of the U.S. Army on an epic flight to freedom of over 1,170 miles (1,880 km) across four states and multiple mountain ranges. Two hundred Nez Perce warriors defeated or held off the pursuing troops in 18 battles, skirmishes, and engagements in which more than 100 soldiers and 100 Nez Perce (including women and children) were killed.[13]

A majority of the surviving Nez Perce were finally forced to surrender on October 5, 1877, after the Battle of the Bear Paw Mountains in Montana, only 40 miles (64 km) from the Canadian border. Chief Joseph surrendered to General Oliver O. Howard of the U.S. Cavalry.[14] During the surrender negotiations, Chief Joseph sent a message, usually described as a speech, to the soldiers which is often considered one of the greatest American speeches: "...Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."[15]

The route of the Nez Perce flight is preserved by the Nez Perce National Historic Trail.[16] The annual Cypress Hills ride in June commemorates the Nez Perce people's crossing into Canada.[17]

Nez Perce horse breeding program

The Nez Perce tribe began a breeding program in 1994 based on crossbreeding the Appaloosa and a Central Asian breed called Akhal-Teke to produce the Nez Perce Horse.[18] This is a program to re-establish the horse culture of the Nez Perce, a proud tradition of selective breeding and horsemanship that was destroyed in the 19th century. The breeding program was financed by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, the Nez Perce tribe and a nonprofit group called the First Nations Development Institute (based in Washington D.C.), which promotes such businesses in Indian country. These horses that the Nez Perce had developed were known for their speed.

Fishing

Fishing is an important ceremonial, subsistence, and commercial activity for the Nez Perce tribe. Nez Perce fishers participate in tribal fisheries in the mainstream Columbia River between Bonneville Dam and McNary Dam. The Nez Perce also fish for spring and summer Chinook salmon and steelhead in the Snake River and its tributaries. The Nez Perce tribe runs the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery on the Clearwater River as well as several satellite hatchery programs.

Nez Perce Indian Reservation

The current tribal lands consist of a reservation in north central Idaho at , primarily in the Camas Prairie region south of the Clearwater River, in parts of four counties. In descending order of surface area, the counties are Nez Perce, Lewis, Idaho, and Clearwater. The total land area is about 1,195 square miles (3,100 km²), and the reservation's population at the 2000 census was 17,959.[19] Its largest community is the city of Orofino, near its northeast corner. Lapwai, the seat of tribal government, has the highest percentage of Nez Perce people, at about 81.4 percent.

Similar to the opening of lands in Oklahoma, the U.S. government opened the reservation for white settlement on November 18, 1895. The proclamation had been signed less than two weeks earlier by President Cleveland.[20][21][22][23]

Communities

|

|

|

In addition, the Colville Indian Reservation in eastern Washington contains the Joseph band of Nez Perce.

Notable Nez Perce

- Old Chief Joseph was leader of the Wallowa Band and one of the first Nez Percé converts to Christianity and vigorous advocate of the tribe's early peace with whites, father of Chief Joseph (also known as Young Joseph).

- Chief Joseph the best-known leader of the Nez Perce, who led his people in their struggle to retain their identity, with about 60 warriors, he commanded the greatest following of the non-treaty chiefs.

- Ollokot, younger brother of Chief Joseph, war chief of the Wallowa band, was killed while fighting at the final battle on Snake Creek, near the Bear Paw Mountains on October 4, 1877.

- Looking Glass, (Allalimya Takanin) leader of the non-treaty Alpowai band and war leader, who was killed during the tribe's final battle with the US Army, his following was third and did not exceed 40 men.

- Eagle from the Light,[24] (Tipiyelehne Ka Awpo) chief of the non-treaty Lam'tama band, that traveled east over the Bitterroot Mountains along with Looking Glass' band to hunt buffalo, was present at the Walla Walla Council in 1855 and supported the non-treaty faction at the Lapwai Council, refused to sign the Treaty of 1855 and 1866, left his territory on Salmon River (two miles south of Corvallis) in 1875 with part of his band, and did settle down in Weiser County (Montana), joined with Shoshone Chief's Eagle's Eye. The leadership of the other Lam'tama that rested on the Salmon River was took by old chief White Bird. Eagle From the Light didn't participate in the War of 1877 because he was too far away.

- Peo Peo Tholekt (piyopyóot’alikt - "Bird Alighting”), a Nez Perce warrior who fought with distinction in every battle of the Nez Perce War, wounded in the Battle of Camas Creek.

- White Bird (Peo-peo-hix-hiix, piyóopiyo x̣ayx̣áyx̣ or more correctly Peopeo Kiskiok Hihih - "White Goose”), also referred to as White Pelican was war leader and tooat (Medicine man (or Shaman) or Prophet) of the non-treaty Lamátta or Lamtáama band, belonging to Lahmatta ("area with little snow”), by which White Bird Canyon was known to the Nez Perce, his following was second in size to Joseph's, and did not exceed 50 men

- Toohoolhoolzote, was leader and tooat (medicine man (or shaman) or prophet) of the non-treaty Pikunan band; fought in the Nez Perce War after first advocating peace; died at the Battle of Bear Paw

- Yellow Wolf (He–Mene Mox Mox, himíin maqsmáqs, wished to be called Heinmot Hihhih or In-mat-hia-hia - "White Lightning,” c. 1855, died August 1935) was a Nez Perce warrior of the non-treaty Wallowa band who fought in the Nez Perce War of 1877, gunshot wound, left arm near wrist; under left eye in the Battle of the Clearwater

- Yellow Bull (Chuslum Moxmox, Cúuɫim maqsmáqs), war leader of a non-treaty band

- Wrapped in the Wind (’elelímyeté'qenin’/ háatyata'qanin')

- Rainbow (Wahchumyus), war leader of a non-treaty band, killed in the Battle of the Big Hole

- Five Wounds (Pahkatos Owyeen), wounded in right hand at the Battle of the Clearwater and killed in the Battle of the Big Hole

- Red Owl (Koolkool Snehee), war leader of a non-treaty band

- Poker Joe, warrior and subchief; chosen trail boss and guide of the Nez Percé people following the Battle of the Big Hole, killed in the Battle of Bear Paw; half French Canadian and Nez Perce descent

- Hallalhotsoot (Halalhot'suut, c.1796 - Jan. 3, 1876), known to whites as "Lawyer," son of a Salish-speaking Flathead woman and Twisted Hair, the Nez Perce who welcomed and befriended Lewis and Clark in the fall of 1805. His father's positive experiences with the whites greatly influenced him, leader of the treaty faction of the Nez Percé, signed the Walla Walla Treaty of 1855

- Timothy (Tamootsin, 1808–1891), leader of the treaty faction of the Alpowai (or Alpowa) band of the Nez Percé, was the first Christian convert among the Nez Percé, was married to Tamer, a sister of Old Chief Joseph, who was baptized on the same day as Timothy.[25]

- Archie Phinney (1904–1949), scholar and administrator who studied under Franz Boas at Columbia University and produced Nez Perce Texts, a published collection of Nez Perce myths and legends from the oral tradition[26]

- Elaine Miles, actress best known from her role in television's Northern Exposure

- Jack and Al Hoxie, silent film actors; mother was Nez Perce

- Jackson Sundown, war veteran and rodeo champion

- Claudia Kauffman, a former state senator in Washington state

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 2010 Figures for total Nez Perce community. Retrieved 2010.10.05

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Boston: Mariner Books, 1997. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-395-85011-4.

- ↑ R. David Edmunds "The Nez Perce Flight for Justice," American Heritage, Fall 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Aoki, Haruo. Nez Perce Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-520-09763-6.

- ↑ Walker, Deward (1998). Plateau, Handbook of North American Indians v. 12. Smithsonian Institution, 437–438 l. ISBN 0-16-049514-8.

- ↑ Aoki, Haruo (1994). Nez Perce Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press, 52, 542, 527. ISBN 978-0-520-09763-6.

- ↑ Since Time Immemorial. Lewis & Clark Rediscovery Project. Nez Perce Tribe. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Spinden, Herbert Joseph (1908). Nez Percé Indians, Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, v.2 pt.3. American Anthropological Association. OCLC 4760170.

- ↑ Walker, Jr., Deward E. (1964). The Nez Perce. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- ↑ (2007) Lewis & Clark and the Indian Country: the Native American Perspective. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 66–67. ISBN 0252074858. OCLC 132681406.

- ↑ Research Center. Nez Perce National Historic Park. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin. "The Nez Perce Indians and the opening of the Northwest." Yale University Press, 1971.

- ↑ Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. The Nez Perce and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965, pp. 632–633.

- ↑ Letters and Quotations of the Nez Perce Flight. US Forest Service. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Chief Joseph Surrenders. Great Speeches. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Maps of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail. US Forest Service. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Nez Perce Ride to Freedom. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

- ↑ Nez Perce horse culture resurrected through new breed. Idaho Natives. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Nez Perce Reservation Census of Population. United States Census Bureau (2000). Archived from the original on October 8, 2011.

- ↑ Hamilton, Ladd, "Heads were popping up all over the place", June 25, 1961, p. 14.

- ↑ Brammer, Rhonda, "Unruly mobs dashed to grab land when reservation opened", July 24, 1977, p. 6E.

- ↑ "3,000 took part in "sneak" when Nez Perce Reservation was opened", November 19, 1931, p. 3.

- ↑ "Nez Perce Reservation", December 11, 1921, p. 5.

- ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specifiedMcCoy, Robert R. (March 2004). . Routledge Chapman & Hall.

- ↑ The Treaty Trail: U.S.-Indian Treaty Councils in the Northwest. Washington State Historical Society. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Rigby, Barry, "Archie Phinney was a champion of Indian rights", July 3, 1990, p. 4-Centennial.

Further reading

- Beal, Merrill D. "I Will Fight No More Forever"; Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1963.

- Bial, Raymond. The Nez Perce. New York: Benchmark Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7614-1210-7.

- Boas, Franz (1917). Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin tribes, Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection, Published for the American Folk-Lore Society by G.E. Stechert & Co.. OCLC 2322072.

- Will Henry: From where the Sun now stands, New York: Bantam Books, 1976. ISBN 0-553-02581-3.

- Humphrey, Seth K. (1906). Indian dispossessed (DJVU), Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection, Revised, Boston: Little, Brown and Co.. OCLC 4450366.

- Josephy, Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Yale Western Americana series, 10. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

- Judson, Katharine Berry (1912). Myths and legends of the Pacific Northwest, especially of Washington and Oregon, Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection, 2nd, Chicago: A.C. McClurg. OCLC 10363767. Oral traditions from the Chinook, Nez Perce, Klickitat and other tribes of the Pacific Northwest.

- Lavender, David Sievert. Let Me Be Free: The Nez Perce Tragedy. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 0-06-016707-6.

- Nerburn, Kent. Chief Joseph & the Flight of the Nez Perce: The Untold Story of an American Tragedy. New York: HarperSanFrancicso, 2005. ISBN 0-06-051301-2.

- Pearson, Diane. The Nez Perces in the Indian Territory: Nimiipuu Survival. 2008 Indian Studies professor traces the history of the Nez Perces and their maltreatment by the U.S. government. ISBN 978-0-8061-3901-2.

- Stout, Mary. Nez Perce. Native American peoples. Milwaukee, WI: Gareth Stevens Pub, 2003. ISBN 0-8368-3666-9.

- Warren, Robert Penn. Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Who Called Themselves the Nimipu, "the Real People": A Poem. New York: Random House, 1983. ISBN 0-394-53019-5.

External links

- Official tribal site.

- Friends of the Bear Paw, Big Hole & Canyon Creek Battlefields.

- Nez Perce Horse Registry.

- Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission – member tribes include the Nez Perce.

- Nez Perce National Historic Park.

- Nez Perce National Historic Trail.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.