Nag Hammadi (Library)

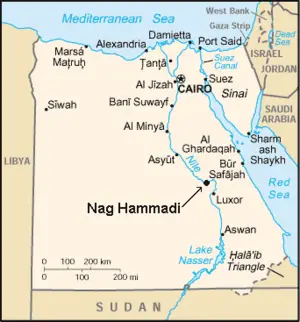

The Nag Hammadi library is a collection of early Christian Gnostic texts discovered near the Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945. Contained in thirteen leather-bound papyrus books, or "codices," buried in a sealed jar, the find is considered the most important archaeological discovery in the modern period relating to the history of early Christianity.

The Nag Hammadi writings comprise fifty-two mostly Gnostic gospels, apocalypses, and esoteric treatises. They also include three monastic works belonging to the Corpus Hermeticum and a partial translation of Plato's Republic. The codices are believed to be a "library," or collection, hidden by monks from the nearby monastery of St. Pachomius after the possession of such banned writings became a serious offense. The zeal of the powerful fourth century bishop Athanasius of Alexandria in suppressing heretical writings and the Theodosian decrees of the 390s strenthening the legal position of orthodoxy may have motivated the hiding of such dangerous literature. Because of the success of the orthodox church in destroying heretical works, many of the books discovered at Nag Hammadi had previously been known only by reference.

The most well-known of these works is the Gospel of Thomas, of which the Nag Hammadi codices contain the only complete text. It is considered by many scholars to be quite early and was apparently widely read in certain Christian communities. Two Nag Hammadi books — the Gospel of Philip and the Gospel of Mary Magdalene — figured prominently in the popular novel and movie The Davinci Code by Dan Brown.

The contents of the codices were written in Coptic, though the works were probably all translations from Greek. A first or second century date of composition for most of the lost Greek originals has been proposed, though this is disputed. The manuscripts themselves date from the third and fourth centuries. The Nag Hammadi codices are housed in the Coptic Museum in Cairo.

Content and Significance

The signifance of the Nag Hammadi discovery for students of early Christianity and mysticism can hardly be exaggerated. Prior to this discovery, the importance of many of these texts was known mainly because they were denounced as heretical by orthodox writers whose works have survived. Only a few Gnostic works had survived, mostly in fragmentary form. Nag Hammadi produced a treasure trove of Gnostic volumes in close to their original form. Their translation into and current widespread availability had brougth an entire corpus of previously suppressed spiritual literature to the reading public.

While many of the Nag Hammadi books are highly esoteric in nature, some are very accessible to the everyday reader. The Gospel of Thomas, for example, is a simple collections of sayings of Jesus. Many of these sayings are duplicated in the orthodox gospels, but some have a notably Gnostic character. Thomas himself, who is denigrated in the orthodox Gospels for doubting Jesus' physical resurrection, is exalted as the one disciple who truly understand the secret knowledge imparted by Jesus. Scholars such as Elaine Pagels and others have concluded that the reason for Thomas' denigration in the orthodox gospels is that he had become a central figure for those Christians who stressed the teachings of Jesus rather than sacraments and the doctrine of the Resurrection. (The resurrection is not mentioned in Thomas' gospel.)

Other Nag Hammadi writings give additional insights into the nature of second century Gnostic Christianity, its beliefs and traditions, as well as its struggle with the orthodox church.

The Gospel of Truth describes a Gnostic accountof creation and the origin of evil throughthe fall of Sophia (wisdoem) Norea. It presents Jesus as having been sent down by God to remove the ignorance.

The Gospel of Philip presents Mary Magdalene as the disciple most beloved of Jesus, fueling speculation that she may have been his wife.

The Apocryphon of John describes Jesus reappearing and giving secret knowledge to the apostles Peter and John after having ascended to heaven.

Several of the books are "Sethian" in character, presenting revelations spiritual teachings in the name of the third son of Adam, Seth. Others are ostensibly the works of known Gnostic teachers such as Valeninus, Silvanus, and others.

The writings have been classified [1] as follows:

Sayings and Acts of Jesus: The Dialogue of the Saviour; The Book of Thomas the Contender; The Apocryphon of James; The Gospel of Philip; The Gospel of Thomas.

Writings dealing with the Divine Feminine: The Thunder, Perfect Mind; The Thought of Norea; The Sophia of Jesus Christ; The Exegesis on the Soul.

Lives and experiences of the apostles: The Apocalypse of Peter; The Letter of Peter to Philip; The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles; The (First) Apocalypse of James; The (Second) Apocalypse of James, The Apocalypse of Paul.

Creation and Redemption: The Apocryphon of John; The Hypostasis of the Archons; On the Origin of the World; The Apocalypse of Adam; The Paraphrase of Shem.

Commentaries on the nature of reality, the soul, etc: The Gospel of Truth; The Treatise on the Resurrection; The Tripartite Tractate; Eugnostos the Blessed; The Second Treatise of the Great Seth; The Teachings of Silvanus; The Testimony of Truth.

Liturgical and initiatory texts: The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth; The Prayer of Thanksgiving; A Valentinian Exposition; The Three Steles of Seth; The Prayer of the Apostle Paul. (Also The Gospel of Philip.)

Discovery

The story of the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 has been described as 'exciting as the contents of the find itself' (Markschies, Gnosis: An Introduction, 48). In December of that year, two Egyptian brothers found several papyri in a large earthernware vessel while digging for fertilizer around limestone caves near present-day Habra Dom in Upper Egypt. The find was not initially reported by either of the brothers, who sought to make money from the manuscripts by selling them individually at intervals. It is also reported that the brothers' mother burned several of the manuscripts, worried, apparently, that the papers might have 'dangerous effects' (Markschies, Gnosis, 48). As a result, what came to be known as the Nag Hammadi library (owing to the proximity of the find to Nag Hammadi, the nearest major settlement) appeared only gradually, and its significance went unacknowledged until some time after its initial uncovering.

In 1946, the brothers became involved in a feud, and left the manuscripts with a Coptic priest, whose brother-in-law in October that year sold a codex to the Coptic Museum in Old Cairo (this tract is today numbered Codex III in the collection). The resident Coptologist and religious historian Jean Dorese, realising the significance of the artifact, published the first reference to it in 1948. Over the years, most of the tracts were passed by the priest to a Cypriot antiques dealer in Cairo, thereafter being retained by the Department of Antiquities, for fear that they would be sold out of the country. After the revolution in 1956, these texts were handed to the Coptic Museum in Cairo, and declared national property.

Meanwhile, a single codex had been sold in Cairo to a Belgian antique dealer. After an attempt was made to sell the codex in both New York and Paris, it was acquired by the Carl Gustav Jung Institute in Zurich in 1951, through the mediation of Gilles Quispel. There it was intended as a birthday present to the famous psychologist; for this reason, this codex is typically known as the Jung Codex, being Codex I in the collection.

Jung's death in 1961 caused a quarrel over the ownership of the Jung Codex, with the result that the pages were not given to the Coptic Museum in Cairo until 1975, after a first edition of the text had been published. Thus the papyri were finally brought together in Cairo: of the 1945 find, eleven complete books and fragments of two others, 'amounting to well over 1000 written pages' (Markschies, Gnosis: An Introduction, 49) are preserved there.

Translation

The first edition of a text found at Nag Hammadi was from the Jung Codex, a partial translation of which appeared in Cairo in 1956, and a single extensive facsimile edition was planned. Due to the difficult political circumstances in Egypt, individual tracts followed from the Cairo and Zurich collections only slowly.

This state of affairs changed only in 1966, with the holding of the Messina Congress in Italy. At this conference, intended to allow scholars to arrive at a group consensus concerning the definition of gnosticism, James M. Robinson, an expert on religion, assembled a group of editors and translators whose express task was to publish a bilingual edition of the Nag Hammadi codices in English, in collaboration with the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity in Claremont, California. Robinson had been elected secretary of the International Committee for the Nag Hammadi Codices, which had been formed in 1970 by UNESCO and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture; it was in this capacity that he oversaw the project. In the meantime, a facsimile edition in twelve volumes did appear between 1972 and 1977, with subsequent additions in 1979 and 1984 from publisher E.J. Brill in Leiden, called The Facsimile Edition of the Nag Hammadi Codices, making the whole find available for all interested parties to study in some form.

At the same time, in the former German Democratic Republic a group of scholars - including Alexander Bohlig, Martin Krause and New Testament scholars Gesine Schenke, Hans-Martin Schenke and Hans-Gebhard Bethge - were preparing the first German translation of the find. The last three scholars prepared a complete scholarly translation under the auspices of the Berlin Humboldt University, which was published in 2001.

The James M. Robinson translation was first published in 1977, with the name The Nag Hammadi Library in English, in collaboration between E.J. Brill and Harper & Row. The single-volume publication, according to Robinson, 'marked the end of one stage of Nag Hammadi scholarship and the beginning of another' (from the Preface to the third revised edition). Paperback editions followed in 1981 and 1984, from E.J. Brill and Harper respectively. This marks the final stage in the gradual dispersal of gnostic texts into the wider public arena - the full compliment of codices was finally available in unadulterated form to people around the world, in a variety of languages.

A further English edition was published in 1987, by Harvard scholar Bentley Layton, called The Gnostic Scriptures: A New Translation with Annotations (Garden City: Doubleday & Co., 1987). The volume unified new translations from the Nag Hammadi Library with extracts from the heresiological writers, and other gnostic material. It remains, along with The Nag Hammadi Library in English one of the more accessible volumes translating the Nag Hammadi find, with extensive historical introductions to individual gnostic groups, notes on translation, annotations to the text and the organisation of tracts into clearly defined movements.

Complete list of codices found in Nag Hammadi

Note: Translated texts and introductory material are available at The Nag Hammadi Library

- Codex I (also known as The Jung Foundation Codex):

- The Prayer of the Apostle Paul

- The Apocryphon of James (also known as the Secret Book of James)

- The Gospel of Truth

- The Treatise on the Resurrection

- The Tripartite Tractate

- Codex II:

- The Apocryphon of John

- The Gospel of Thomas a sayings gospel

- The Gospel of Philip a sayings gospel

- The Hypostasis of the Archons

- On the Origin of the World

- The Exegesis on the Soul

- The Book of Thomas the Contender

- Codex III:

- The Apocryphon of John

- The Gospel of the Egyptians

- Eugnostos the Blessed

- The Sophia of Jesus Christ

- The Dialogue of the Saviour

- Codex IV:

- The Apocryphon of John

- The Gospel of the Egyptians

- Codex V:

- Eugnostos the Blessed

- The Apocalypse of Paul

- The First Apocalypse of James

- The Second Apocalypse of James

- The Apocalypse of Adam

- Codex VI:

- The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles

- The Thunder, Perfect Mind

- Authoritative Teaching

- The Concept of Our Great Power

- Republic by Plato - The original is not gnostic, but the Nag Hammadi library version is heavily modified with current gnostic concepts.

- The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth - a Hermetic treatise

- The Prayer of Thanksgiving (with a hand-written note) - a Hermetic prayer

- Asclepius 21-29 - another Hermetic treatise

- Codex VII:

- The Paraphrase of Shem

- The Second Treatise of the Great Seth

- Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter

- The Teachings of Silvanus

- The Three Steles of Seth

- Codex VIII:

- Zostrianos

- The Letter of Peter to Philip

- Codex IX:

- Melchizedek

- The Thought of Norea

- The Testimony of truth

- Codex X:

- Marsanes

- Codex XI:

- The Interpretation of Knowledge

- A Valentinian Exposition, On the Anointing, On Baptism (A and B) and On the Eucharist (A and B)

- Allogenes

- Hypsiphrone

- Codex XII

- The Sentences of Sextus

- The Gospel of Truth

- Fragments

- Codex XIII:

- Trimorphic Protennoia

- On the Origin of the World

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Layton, Bentley (1987). The Gnostic Scriptures. SCM Press. ISBN 0-334-02022-0.

- Markschies, Christoph (trans. John Bowden), (2000). Gnosis: An Introduction. T & T Clark. ISBN 0-567-08945-2.

- Pagels, Elaine (1979). The Gnostic Gospels. ISBN 0679724532.

- Robinson, James (1978). The Nag Hammadi Library in English. ISBN 0-06-066934-9.

- Robinson, James M., 1979 "The discovery of the Nag Hammadi codices," in Biblical Archaeology vol. 42, pp206–224.

External links

- The Nag Hammadi Library Complete collection of the Nag Hammadi texts, with additional introductory material.

- The Gnostic Society Library Huge collection of authentic Gnostic texts, including the Nag Hammadi scriptures. Part of the Gnosis Archive site.

- Russian translation of The Nag Hammadi library

- Gnosticweb Gnosticweb spiritual group version of Nag Hammadi

- The Religious Texts Index: Nag Hammadi Library

- The Gospel of Thomas

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.