Mohawk

| Mohawk | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Total population | ||||||

| 28,000 | ||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

| ||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| English, Mohawk | ||||||

| Religions | ||||||

| Christianity, Longhouse | ||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||

| other Iroquoian peoples |

The Mohawk were one of the five core tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy founded between 1450 and 1600. The Mohawk leader, Hiawatha, and Huron prophet, Deganawida, worked together to bring the original tribes together under a peaceful constitution called "The Great Binding Law". It is reported that this document informed the founding fathers of the United States when drafting the constitution for a new nation. The American Revolutionary War divided the Iroquois between Canada and the United States with an exodus led by the Mohawk leader, Joseph Brant, to Canada following the victory of the Americans. In 1763, "Council fires were extinguished for the first time in roughly 200 years." [1]

Introduction

The Mohawk (Kanienkeh, Kanienkehaka or Kanien’Kahake, meaning "People of the Flint") are an indigenous people of North America originally from the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York to southern Quebec and eastern Ontario. Their current settlements include areas around Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River in Canada. ("Canada" itself is a Mohawk word.) Their traditional homeland stretches from south of the Mohawk River, east to the Green Mountains of Vermont, west to its border with the Oneida Nation, and north to the St Lawrence River. As original members of the Iroquois League, or Haudenosaunee, the Mohawk were known as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door" who guarded the Iroquois Confederation against invasion from that direction. (It was from the east that European settlers first appeared, sailing up the Hudson River to found Albany, New York, in the early 1600s.)

Origins of name

The name of the Mohawk people in the Mohawk language is Kanien'kehá:ka, alternately attributed various spellings by early French-settler ethnographers including one such spelling as, Canyenkehaka. There are various theories as to why the Mohawk were called the "Mohawk" by Europeans. One theory holds that the name "Mohawk" was bestowed upon the tribe by German mercenaries and immigrants settled near Fort Orange in Mohawk Valley that were fighting with the British troops, who, mistaking by a personal pidgin in relation with others they had intertwined, derived the well known pronunciation for the Kanien'kehá:ka tribe as "Moackh." An English language corruption of pronunciation turned the original Mohawk Valley German-Dutch pidgin of the Kanien' kehá:ka name into the current pronunciation of "Mohawk." A widely-accepted theory is that the name is a combination of the Narraganset word for "man-eaters" (Mohowawog), the Unami term for "cannibal-monsters" (Mhuweyek), an Algonquin term for "ate living creatures" (Mohowaugs), and the Ojibwe term for "bears" (Mawkwas) .

The Dutch referred to the Mohawk as Maquasen, or Maquas. To the French they were Agniers, Maquis, or simply Iroquois.

People of the Flint

To the Mohawk themselves, they are Kanien'kehá:ka and "People of the Flint." The use of People of the Flint is associated with their origins in the Mohawk Valley , and their original homeland in the United States, New York. There, flint deposits were traditionally used in Mohawk bow arrows, and as flint (tools).

History

Before European Contact

History has remembered the name of the Mohawk leader, Hiawatha, for his work bringing peace to the Iroquois Nation and for a poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow centuries after his death.

Hiawatha (also known as Ayenwatha or Ha-yo-went'-ha; Onondaga Hayę́hwàtha)[2] who lived (depending on the version of the story) in the 1100s, 1400s, or 1500s, was variously a leader of the Onondaga and Mohawk nations of Native Americans.

Hiawatha was a follower of The Great Peacemaker, a prophet and spiritual leader who was credited as the founder of the Iroquois confederacy, (referred to as Haudenosaunee by the people). If The Great Peacemaker was the man of ideas, Hiawatha was the politician who actually put the plan into practice. Hiawatha was a skilled and charismatic orator, and was instrumental in persuading the Iroquois peoples, the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Cayugas, and Mohawks, a group of Native North Americans who shared similar languages, to accept The Great Peacemaker's vision and band together to become the Five Nations of the Iroquois confederacy. (Later, in 1721, the Tuscarora nation joined the Iroquois confederacy, and they became the Six Nations).

After European Contact

A 1634 Dutch expedition from Fort Orange (present-day Albany, New York) to the Mohawk settlements to the west was led by a surgeon named Harmen van den Bogaert. At the time of the expedition there were only eight villages (from east to west): Onekahoncka, Canowarode, Schatsyerosy, Canagere, Schanidisse, Osquage, Cawaoge, and Tenotoge. All villages were on the south side of the river, between present-day Fonda and Fort Plain. The first (Onekahoncka) being situated on the south side of the Mohawk River where it meets the Cayadutta Creek, and the last being on the south side of the Mohawk River where it meets the Caroga Creek.

During the seventeenth century, the Mohawks were allied with the Dutch at Fort Orange, New Netherland. Their Dutch trade partners equipped the Mohawks to fight against other nations allied with the French, including the Ojibwes, Huron-Wendats, and Algonquins. After the fall of New Netherland to the English, the Mohawks became allies of the English Crown. From the 1690s, they underwent a period of Christianization, during which many were baptized with English first names.

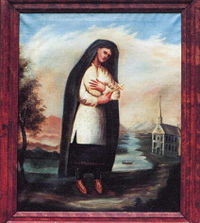

One large group of Mohawks settled in the vicinity of Montreal. From this group descend the Mohawks of Kahnawake, Akwesasne and Kanesatake. One of the most famous Catholic Mohawks was Kateri Tekakwitha, who was later beatified. Tekakwitha (1656 – April 17, 1680) was the daughter of a Mohawk warrior and a Christian Algonquin woman. At the age of four, smallpox swept through Ossernenon, and Tekakwitha was left with unsightly scars and poor eyesight. The outbreak took the lives of her brother and both her parents. She was then adopted by her uncle, who was the chief of the Turtle-clan. As the adopted daughter of the chief, she was courted by many of the warriors looking for her hand in marriage. However, during this time she began taking interest in Christianity. Tekakwitha was converted and baptized in 1676 by Father Jacques de Lamberville, a Jesuit. At her baptism, she took the name "Kateri," a Mohawk pronunciation of "Catherine." Unable to understand her zeal, members of the tribe often chastised her, which she took as a testament to her faith.

She is called "The Lily of the Mohawks," the "Mohawk Maiden," the "Pure and Tender Lily," and the "Fairest Flower among True Men."[3]

The Mohawk Nation, as part of the Iroquois Confederacy, were recognized for some time by the British government, and the Confederacy was a participant in the Congress of Vienna, having been allied with the British during the War of 1812 which was viewed by the British as part of the Napoleonic Wars. However, in 1842 their legal existence was overlooked in Lord Durham's report on the reform and organization of the Canadas.

Chief John Smoke Johnson (December 2 or 14, 1792 - August 26, 1886) or Sakayengwaraton (also known as Smoke Johnson), was a Mohawk leader who participated in the War of 1812. His granddaughter, Emily Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (March 10, 1861 - March 7, 1913), was a Canadian writer and performer. She is often remembered for her poems that celebrate her heritage. One such poem is the frequently anthologized “The Song my Paddle Sings.”

The Four Mohawk Kings or Four Kings of the New World were the three three Mohawk and one Mahican Chiefs of the Iroquoian Confederacy. The three Mohawk were: Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow of the Bear Clan, called King of Maguas, with the Christian name Peter Brant, grandfather of Joseph Brant; Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row of the Wolf Clan, called King of Canojaharie, or John of Canojaharie ("Great Boiling Pot"); and Tee Yee Ho Ga Row, meaning "Double Life," of the Wolf Clan, called King Hendrick, with the Christian name Hendrick Peters. The one Mahican was Etow Oh Koam of the Turtle Clan, labeled in his portrait as Emperor of the Six Nations. It was these four First Nations leaders who visited Queen Anne in 1710 as part of a diplomatic visit organized by Pieter Schuyler. Five set out on the journey, but one died in mid-Atlantic. They were received in London as diplomats, being transported through the streets of the city in Royal carriages, and received by Queen Anne at the Court of St. James Palace. They also visited the Tower of London and St. Paul's Cathedral. To commemorate this visit Jan Verelst was commissioned to paint the portraits of the Four Kings.

During the era of the French and Indian War, Anglo-Mohawk relations were maintained by men such as Sir William Johnson (for the British Crown), Conrad Weiser (on behalf of the colony of Pennsylvania), and King Hendrick (for the Mohawks). The Albany Congress of 1754 was called in part to repair the damaged diplomatic relationship between the British and Mohawks.

Because of unsettled conflicts with Anglo-American settlers infiltrating into the Mohawk Valley and outstanding treaty obligations to the Crown, the Mohawks generally fought against the United States during the American Revolutionary War, the Northwest Indian War, and the War of 1812. After the American victory in the revolutionary war, one prominent Mohawk leader, Joseph Brant, led a large group of Iroquois out of New York to a new homeland at Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario. On November 11, 1794, representatives of the Mohawks (along with the other Iroquois nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States.

Iroquois Confederacy

The original five Iroquois tribes were united between 1450 and 1600 by a Mohawk statesman, Hiawatha, and religious leader, Deganawida.[4] Hiawatha went from tribe to tribe speaking for Deganawida who had a speech impediment.[5] Scholars write that a "Clan Mother," Jigonsaseh, was also a co-founder of the Confederacy.[6] The tribes that united were Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca. The purpose for the uniting was to end the inter-tribal wars and bring peace and well-being to all of the tribes. A sixth tribe, the Tuscarora, joined later after the confederacy was formed.

The Mohawk, as well as other Iroquois tribes, met white explorers in the sixteenth century. In 1656, Jesuit missionaries Joseph Chaumanot and René Menard came to the area from Onondaga territory, said to be invited by the Cayuga chief Saonchiogwa. They were followed later by Étienne de Carheil and Pierre Raffeix. The Jesuits built the first Christian church west of Onondaga territory in Goiogouen, which they called St. Joseph.

At the first visit of the Jesuits, Goiogouen was described as "a village [of] long houses with ridge-pole roofs covered with elm bark... in the midst of fields of corn which extended to the edge of the forest." In 1671, Raffeix described the country surrounding Goiogouen as follows:

Goiogouen is the fairest country I have seen in America. It is a tract between two lakes and not exceeding four leagues in width, consisting of almost uninterrupted plains, the woods bordering it are extremely beautiful. Around Goiogouen there are killed more than a thousand deer annually. Fish, salmon, as well as eels and other fish are plentiful. Four leagues from here I saw by the side of a river (Seneca) ten extremely fine salt springs.

At the time of the American Revolution, Goiogouen consisted of "fifteen very large square log houses" (longhouses), deemed to be very well built by the scouting parties of the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign; and "in the vicinity...were one hundred and ten acres of corn; besides apples, peaches, potatoes, turnips, onions, pumpkins, squashes and other vegetables in abundance." The village was destroyed by these American troops on September 23, 1779.

On November 11, 1794, the (New York) Mohawk Nation (along with the other Haudenosaunee nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States. The treaty established peace and friendship between the United States of America and the Six Nations of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee), and affirmed Haudenosaunee land rights in New York State.

Culture

Religion

According to tradition, a supreme creator, Orenda, was recognized in the festivals held for harvest, maple sap, strawberries, and corn. An eight-day event in midwinter was held to forgive past wrongs. Other animate and inanimate objects were considered to have a spiritual value. Celebration of the maple sap and strawberries as well as corn planting were considered spiritual in nature. Also, in the winter, there was an important eight-day festival to give thanks and to forget past wrongs.

In the early nineteenth century the teachings of Handsome Lake became popular. Handsome Lake was a Seneca who taught about Jesus and also blended the traditional celebrations with Christian-style confessions of sin and urged Native Americans to stay away from alcohol. His teachings eventually were incorporated into the Longhouse religion, which continues to have followers today. This period was known as the Second Great Awakening. "Beginning in 1979, the Seneca Handsome Lake spoke of Jesus and called upon Iroquois to give up alcohol and other negative behaviors such as witchcraft and promiscuity. He also exhorted them to maintain their traditional religious celebrations. [7]

Government

There were 50 chiefs (Sachems) of the Iroquois League. All the chiefs were men. The Mohawk sent nine sachems to the great council each fall. The shield was the symbol of their gathering. There was a chief or headman in each village. The decision at all levels was based on consensus which included women, who could act as regents. Women nominated and recalled clan chiefs.

"The creators of the U.S. government used the Iroquois League as a model of democracy." [8] The Constitution of the Iroquois Nation was titled, The Great Binding Law, Gayanashagowa. It opens with this line:

I am Dekanawidah and with the Five Nations Confederate Lords I plant the Tree of Great Peace. I plant it in your territory, Adodarhoh, and the Onondaga Nation, in the territory of you who are Firekeepers.[9]

Customs

The Mohawk recognized a dual division, each composed of three matrilineal, animal-named clans (Wolfe, Bear, and Turtle). Women were highly regarded and were equated with the "three sisters" corn, beans, and squash. Intra-village activities included gambling and lacrosse games. Food was shared so that all were equal.

Shamans used plant medicines for healing.

Suicide was committed on occasion due to dishonor or abandonment. Murder was avenged or paid for with gifts. The dead were buried in sitting position with food and tools for use in the spirit world. A ceremony was held after ten days.[10]

The Summer Initiation Festival is held at the beginning of May each year. Mohawks gather to celebrate the coming of summer and the life it brings. This has been a very respected and honored festival of the Mohawk people for several thousands of years. For five days, the Mohawks perform various rituals, such as planting new seeds that will flourish into plants over the summer, that honor and celebrate Mother Earth for the life she is giving to the Earth. The Mohawks believe that winter is a time of death in which Mother Earth goes into a long slumber, in which many plants die, but when spring arrives and nature begins to flourish, she has woken up and given life once again.

Traditional Mohawk hair

The Mohawks, like many indigenous tribes in the Great Lakes region, sometimes wore a hair style in which all their hair would be cut off except for a narrow strip down the middle of the scalp from the forehead to the nape, that was approximately three finger widths across. This style was only used by warriors going off to war. The Mohawks saw their hair as a connection to the creator, and therefore grew it long. But when they went to war, they cut all or some of it off, leaving that narrow strip. The women wore their hair long often with traditional bear grease or tied back into a single braid. Today the hairstyle of the Mohawk is still called a "Mohawk" (or, in Britain, a "Mohican," because this enemy-tribe used it as a disguise during war).

Traditional Mohawk dress

Traditional dress of the Kanien'kehá:ka consisted of women going topless with a skirt of deerskin or a full woodland deerskin dress, long fashioned hair or a braid and Bear Grease otherwise nothing on their head, several ear piercings adorned by shell earrings, shell necklaces, and puckered seam moccasins. The men wore a breech cloth of deerskin in summer, deerskin leggings and a full piece deerskin shirt in winter, several shell strand earrings, shell necklaces, long fashioned hair or a three finger width forehead to nape hair row which stood approximately three inches from the head, and puckered seamed moccasins. During summer children wore nothing and went naked even until about age 14. Later dress after European contact combined some cloth pieces such as the male's ribbon shirt in addition to the place of the deerskin clothing.

Haiwatha

Hiawatha (also known as Ayenwatha or Ha-yo-went'-ha; Onondaga Hayę́hwàtha)[11] who lived (depending on the version of the story) in the 1100s, 1400s, or 1500s, was variously a leader of the Onondaga and Mohawk nations of Native Americans.

Hiawatha was a follower of The Great Peacemaker, a prophet and spiritual leader who was credited as the founder of the Iroquois confederacy, (referred to as Haudenosaunee by the people). If The Great Peacemaker was the man of ideas, Hiawatha was the politician who actually put the plan into practice. Hiawatha was a skilled and charismatic orator, and was instrumental in persuading the Iroquois peoples, the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Cayugas, and Mohawks, a group of Native North Americans who shared similar languages, to accept The Great Peacemaker's vision and band together to become the Five Nations of the Iroquois confederacy. Later, in 1721, the Tuscarora nation joined the Iroquois confederacy, and they became the Six Nations).

Hiawatha is also the name of the legendary hero of the Ojibwa as described in Longfellow's famous epic poem, The Song of Hiawatha. Longfellow said that he based his poem on Schoolcraft's Algic Researches and History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Schoolcraft in turn seems to have based his "Hiawatha" primarily on the Algonquian trickster-figure Nanabozho. There is little or no resemblance between Longfellow's hero and the life-stories of Hiawatha and The Great Peacemaker.

Intentionally epic in scope, Longfellow himself described it as "this Indian Edda," and wrote it in the same meter as the Finnish folk-epic, The Kalevala. The connections between the poem and the Kalevala were never acknowledged by Longfellow, and were the subject of scholarly debate until well into the 1960s. Longfellow took the name from works by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, whom he acknowledged as his main sources. In 1856 Schoolcraft published The Hiawatha Legends, based on this material.

In his notes on the poem, Longfellow cites Schoolcraft as a source for "a tradition prevalent among the North American Indians, of a personage of miraculous birth, who was sent among them to clear their rivers, forests, and fishing-grounds, and to teach them the arts of peace. He was known among different tribes by the several names of Michabou, Chiabo, Manabozo, Tarenyawagon, and Hiawatha." Longfellow's notes make no reference to the Iroquois or the Iroquois League or to any historical personage.

According to ethnologist Horatio Hale (1817-1896), there was a longstanding confusion between the Iroquois leader Hiawatha and the Iroquois deity Aronhiawagon due to "an accidental similarity in the Onondaga dialect between [their names]." The deity, he says, was variously known as Aronhiawagon, Tearonhiaonagon, Taonhiawagi, or Tahiawagi; the historical Iroquois leader, as Hiawatha, Tayonwatha or Thannawege. Schoolcraft "made confusion worse ... by transferring the hero to a distant region and identifying him with Manabozho, a fantastic divinity of the Ojibways. [Schoolcraft's book] has not in it a single fact or fiction relating either to Hiawatha himself or to the Iroquois deity Aronhiawagon."

Contemporary Mohawk

Members of the Mohawk tribe now live in settlements spread throughout New York State and southeastern Canada. Among these are Ganienkeh and Kanatsiohareke in northeast New York, Akwesasne (St. Regis) along the Ontario-New York State border, Kanesatake (Oka) and Kahnawake in southern Quebec, and Tyendinaga and Wahta (Gibson) in southern Ontario. Mohawks also form the majority on the mixed Iroquois reserve, Six Nations of the Grand River, in Ontario. There are also Mohawk Orange Lodges in Canada.

Many Mohawk communities have two sets of chiefs that exist in parallel and are in some sense rivals. One group are the hereditary chiefs nominated by clan matriarchs in the traditional fashion; the other are elected chiefs with whom the Canadian and US governments usually deal exclusively. Since the 1980s, Mohawk politics have been driven by factional disputes over gambling. Both the elected chiefs and the controversial Warrior Society have encouraged gaming as a means of ensuring tribal self-sufficiency on the various reserves/reservations, while traditional chiefs have opposed gaming on moral grounds and out of fear of corruption and organized crime. Such disputes have also been associated with religious divisions: the traditional chiefs are often associated with the Longhouse tradition, practicing consensus-democratic values, while Warrior Society has attacked that religion in favor of their rebellious nature. Meanwhile, the elected chiefs have tended to be associated (though in a much looser and general way) with democratic values. The Government of Canada when ruling the Indians imposed English schooling and separated families to place children in English boarding schools. Like other tribes, Mohawks have mostly lost their native language and many have left the reserve to meld with the English Canadian culture.

The "Oka Crisis" was a land dispute between the Mohawk nation and the town of Oka, Quebec which began on July 11, 1990, and lasted until September 26, 1990. It resulted in three deaths, and would be the first of a number of well-publicized violent conflicts between Indigenous people and the Canadian government in the late twentieth century.

The crisis developed from a dispute between the town of Oka and the Mohawk community of Kanesatake. The Mohawk nation had been pursuing a land claim which included a burial ground and a sacred grove of pine trees near Kanesatake. This brought them into conflict with the town of Oka, which was developing plans to expand a golf course onto the land.

In 1961, a nine-hole golf course, le Club de golf d'Oka, was built on land. The Mohawk launched a legal protest against construction. By the time the case was heard, much of the land had already been cleared and construction had begun on a parking lot and golf greens adjacent to the Mohawk cemetery.

In 1977, the band filed an official land claim with the federal Office of Native Claims regarding the land. The claim was accepted for filing, and funds were provided for additional research of the claim. Nine years later, the claim was finally rejected for failing to meet key criteria.[12]

On October 15, 1993, New York State Governor Mario Cuomo entered into the "Tribal-State Compact Between the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe and the State of New York." The compact purported to allow the Tribe to conduct gambling, including games such as baccarat, blackjack, craps, and roulette, on the Akwesasne Reservation in Franklin County under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA). This decision met with controversy but was finally ratified. The tribe has continued to seek approval to own and operate additional casinos in New York State.

Notes

- ↑ Pritzker,2000. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford Press, p. 436. ISBN 019513897x

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 080613576X pg. 166

- ↑ Bunson, Margaret and Stephen, "Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, Lily of the Mohawks," Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions brochure, pg.1

- ↑ Priztker, H. 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples, NY:Oxford Press, p 412

- ↑ Krech, S., 2005. "Shades of Hiawatha: Staging Indians 1880 - 1930," Journal of Social History, 39.2, p 550. Retrieved from Questia.com on August 26, 2007.

- ↑ Mann, B., 1997. The Lynx in time Haudenosaunee Women's Tradition and History. American Indian Quarterly, 21. Retrieved from Questia.com on August 26, 20007.

- ↑ Pritzker, B., 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia; History, Culture, and Peoples, Oxford Press. p. 437.

- ↑ Pritzner, 2000, p 413

- ↑ Constitution of the Iroquois Nations: The Great Binding Law, Gayanashagowa Retrieved on July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Pritzker, B., 2000. p. 438

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 080613576X pg. 166

- ↑ The Summer of 1990 Retrieved October 2, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cooper, James (1982). The Last of the Mohicans. Bantam Classics, ISBN 10-0553213296.

- Greer, Allan. 2006. Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195309348

- Pritzker, B., 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples, Oxford Press. ISBN 019513897x.

- Snow, D., 1996. The Iroquois. Blackwell Publishers, New York. ISBN 1-55786-938-3

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

- Mohawk Creation Story. Retrieved on September 22, 2007.

| Iroquois Confederacy | |

|---|---|

| Nations | Cayuga · Mohawk · Oneida · Onondaga · Seneca · Tuscarora |

| Topics | Economy · Languages · Mythology · Great Law of Peace · The Great Peacemaker |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.