Difference between revisions of "Mahabalipuram" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{images OK}}{{started}}{{claimed}} | {{images OK}}{{started}}{{claimed}} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | {{Infobox World Heritage Site | |

| − | + | |Name = Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram | |

| − | + | |Image = [[Image:Rathas-Mahabalipuram.jpg|250px|The ''Rathas'' in Mahabalipuram]] | |

| − | + | |State_Party = {{IND}} | |

| − | + | |Type = Cultural | |

| − | + | |Criteria = i, ii, iii, iv | |

| − | + | |ID = 249 | |

| − | + | |Link = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/249/ | |

| − | + | |Region = [[List of World Heritage Sites in Asia and Australasia|Asia-Pacific]] | |

| − | + | |Year = 1984 | |

| − | + | |Session = 8th | |

| − | + | |Extension = | |

| − | + | |Danger = | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | Mahabalipuram | + | '''Mahabalipuram''' ([[Tamil language|Tamil]]:மகாபலிபுரம்) (also known as '''Mamallapuram''') refers to a [[town]] in [[Kancheepuram district]] in the [[India]]n [[States and territories of India|state]] of [[Tamil Nadu]]. It has an average elevation of 12 [[metre]]s (39 [[foot (unit of length)|feet]]). |

| + | |||

| + | Mahabalipuram had been a [[7th century|7<sup>th</sup> century]] port city of the [[South India]]n dynasty of the [[Pallava]]s around 60 km south from the city of [[Chennai]] in Tamil Nadu. Historians speculate that the town had been named after the Pallava king [[Narasimhavarman I|Mamalla]]. It had numerous historic monuments built between the 7<sup>th</sup> and the [[9th century|9<sup>th</sup> century]]. [[UNESCO]] designated '''Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram''' a [[World Heritage Site]]. | ||

== Landmarks == | == Landmarks == | ||

| − | The monuments | + | The monuments, mostly rock-cut and monolithic, constitute the early stages of [[Dravidian architecture]] wherein [[Buddhist]] elements of design display prominently. Cave temples, monolithic ''rathas'' (chariots), sculpted reliefs and structural temples constitute the majority of the monuments. The pillars have been sculpted in the Dravidian tradition; the sculptures provide excellent examples of Pallava art. |

| − | + | Some historians believe that the area served as a school for young sculptors. The different sculptures, some half finished, may have been examples of different styles of architecture, probably demonstrated by instructors and practiced on by young students. That can be seen in the ''Pancha Rathas'' where each ''Ratha'' has been sculpted in a different style. | |

Some important structures include: | Some important structures include: | ||

| Line 37: | Line 30: | ||

=== Thirukadalmallai === | === Thirukadalmallai === | ||

| − | + | The temple [[Thirukadalmallai]] had been dedicated to Lord [[Vishnu]]. [[Pallava]] King built the temple to safeguard the sculptures from corrosion and destruction by the ocean. Records state that, after building the temple, the remaining temple grounds remained preserved from harm by the sea. | |

{| class="infobox bordered" style="width: 25em; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;" | {| class="infobox bordered" style="width: 25em; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;" | ||

| Line 321: | Line 314: | ||

| − | + | == Underwater city== | |

| − | {{Infobox | + | <!-- See [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Indian cities]] for details —>{{Infobox Indian Jurisdiction | |

| − | | | + | native_name = Mahabalipuram | |

| − | | | + | type = town | |

| − | | | + | latd = 12.63 | longd = 80.17| |

| − | | | + | locator_position = right | |

| − | + | state_name = Tamil Nadu | | |

| − | | | + | district = [[Kancheepuram district|Kancheepuram]] | |

| − | + | leader_title = | | |

| − | | | + | leader_name = | |

| − | | | + | altitude = 12| |

| − | | | + | population_as_of = 2001 | |

| − | | | + | population_total = 12,049| |

| − | | | + | population_density = | |

| + | area_magnitude= sq. km | | ||

| + | area_total = | | ||

| + | area_telephone = 91-44| | ||

| + | postal_code = 603104| | ||

| + | vehicle_code_range = TN-21| | ||

| + | sex_ratio = | | ||

| + | unlocode = | | ||

| + | website = | | ||

| + | footnotes = | | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

According to descriptions by early travel writers from [[Great Britain|Britain]], the area near Mahabalipuram had seven [[pagoda]]s by the sea. Accounts of Mahabalipuram were first written down by British traveller [[John Goldingham]] who was told of the "[[Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram|Seven Pagodas]]" when he visited in 1798. | According to descriptions by early travel writers from [[Great Britain|Britain]], the area near Mahabalipuram had seven [[pagoda]]s by the sea. Accounts of Mahabalipuram were first written down by British traveller [[John Goldingham]] who was told of the "[[Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram|Seven Pagodas]]" when he visited in 1798. | ||

Revision as of 00:38, 2 December 2007

| Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 249 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1984 (8th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Mahabalipuram (Tamil:மகாபலிபுரம்) (also known as Mamallapuram) refers to a town in Kancheepuram district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It has an average elevation of 12 metres (39 feet).

Mahabalipuram had been a 7th century port city of the South Indian dynasty of the Pallavas around 60 km south from the city of Chennai in Tamil Nadu. Historians speculate that the town had been named after the Pallava king Mamalla. It had numerous historic monuments built between the 7th and the 9th century. UNESCO designated Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram a World Heritage Site.

Landmarks

The monuments, mostly rock-cut and monolithic, constitute the early stages of Dravidian architecture wherein Buddhist elements of design display prominently. Cave temples, monolithic rathas (chariots), sculpted reliefs and structural temples constitute the majority of the monuments. The pillars have been sculpted in the Dravidian tradition; the sculptures provide excellent examples of Pallava art.

Some historians believe that the area served as a school for young sculptors. The different sculptures, some half finished, may have been examples of different styles of architecture, probably demonstrated by instructors and practiced on by young students. That can be seen in the Pancha Rathas where each Ratha has been sculpted in a different style.

Some important structures include:

Thirukadalmallai

The temple Thirukadalmallai had been dedicated to Lord Vishnu. Pallava King built the temple to safeguard the sculptures from corrosion and destruction by the ocean. Records state that, after building the temple, the remaining temple grounds remained preserved from harm by the sea.

| Sri Sthalasayana Perumal | |

Sthalasayana Perumal | |

| Temple Name: | ThiruKadalMallai |

|---|---|

| Alias Name: | Sthalasayana Perumal Kovil |

| God Name: | Sri Sthalasayana Perumal |

| Goddess Name: | Nilamangai Thayaar |

| Pushkarni: | Pundarika Pushkarni |

| Vimanam: | GaganaKriti Vimanam |

| Location: | Mahabalipuram |

| State and Country: | TamilNadu, India |

The Sthalasayana Perumal Temple is at Mahabalipuram. The Temple resides as the first and foremost of Mahabalipuram sculputres. It is one of the 108 Divya desam.

The temple

The temple stands on the shore and it was built along with the other sculptures. It is a small temple with two major Shrines for Lord Sthalasayana Perumal and Nilamangai Thayaar. This is the avatrasthalam(Birthplace) of Bhoothathazhwar, the 2nd Azhwar. There is also a separate shrine for Lord Narasimha. The architecture depicts the pallava style. This shrine was built by Pallava kings. Bhoothathazhwar was found in a tank that is opposite to the temple.

Legend

Sage Pundareeka was worshipping Lord Vishnu with Lotus flowers. Once the Sage Pundareeka started piling water from the ocean in order to get the divine vision of Lord Vishnu. Seeing his devotion, Lord Vishnu came in guise as an old man and asked for food. The Sage went to get food for the old man. When he returned he found Lord Vishnu in a Ananthasayana posture and wearing the lotus flowers which was offered by the sage. He then realised that it is Lord himself had come in disguise to bless the devotee.

Sri Sthalasayana Perumal Mahatyam

Lord Sthalasayana Perumal had come personally to fulfill his devotees wishes.

Prasadam

Puliyodharai (Tamarind Rice), Dhadhyonam (Curd Rice), Pongal, Chakkarai Pongal, Vada, Adhirasam, Murukku are offered to Lord as Prasadam.

Darshan, Sevas and Festivals Maasi Makham is an important festival.

Composers

Thirumangai Alvar, Bhoothathalvar have composed beautiful Paasurams on Lord Sthalasayana Perumal and his consort Nilamangai Thayaar. It is one of the compositions in Naalayira Divya Prabandha.

Travel and Stay

There are many lodges at Mahabalipuram and Chennai. Lot of bus facility available from Chennai. It is considered to be a great tourist destination from all over the world.

Descent of the Ganges

- Descent of the Ganges - a giant open-air bas relief

Descent of the Ganges at Mahabalipuram, in the Tamil Nadu state India, is one of a group of monuments that were designated as a World Heritage Site since 1984.[1] It is a giant open-air relief carved of the a monolithic rock. The monuments and sanctuaries were built by the Pallava kings in the 7th and 8th centuries. The legend depicted in the relief is the story of the descent of the sacred river Ganga to earth from the heavens led by Bhagirata. The waters of Ganges are believed to possess supernatural powers.The descent of the Ganges and Arjuna's Penance are portrayed in stone at the Pallava heritage site[2]

Arjuna's Penance

- Arjuna's Penance - relief sculpture on a massive scale extolling an episode from the Hindu epic, The Mahabharata.

Arjuna's Penance is the name of a massive open air bas-relief monolith dating from the 7th century CE located in the town of Mahabalipuram in Southern India. Measuring 96 feet long by 43 feet high, the bas-relief is also known as The Descent of Ganga. The bas-relief has two names, because there is not full agreement regarding which stories the mural depicts.

Two Interpretations

In one interpretation, a figure in the bas-relief who is standing on one leg is said to be Arjuna performing an austerity Tapas to receive a boon from Shiva as an aid in fighting the Mahabharata war. (The boon which Arjuna is said to have received was called Pasupata, Shiva's most powerful weapon).

The bas relief is situated on a rock with a cleft. Above the cleft was a collecting pool, and at one time, water may have flowed along the cleft. Figures within the cleft are said to represent Ganga or the River Ganges and Shiva. This provides the basis for an alternative interpretation of the mural. Rather than Arjuna, the figure performing austerities is said to be Bhagiratha. Bhagiratha is said to have performed austerities so that Ganga might descend to earth and wash over the ashes of his relatives, releasing them from their sins. To break Ganga's fall from heaven to earth, she falls onto Shiva's hair, and is divided into many streams by his tresses.

Figures

One of the notable, and perhaps ironic figures in the bas-relief is the figure of a cat standing on one leg (apparently as an austerity). This may be related to the Panchatantra story of the cat who poses as an ascetic in order to lure a hare and a bird to come near. (When near, he devours them.)

External links

Varaha Cave Temple

- Varaha Cave Temple, a small rock-cut temple dating back to the 7th century.

Varaha Cave Temple, an example of Indian rock-cut architecture dating from the late 7th century, is a rock-cut cave temple located at Mamallapuram, a tiny village south of Chennai in the state of Tamil Nadu, India. The village was a busy port during the 7th and 8th century reign of the Pallava dynasty. The site is famous for the rock-cut caves and the sculptured rock that line a granite hill, including one depicting Arjuna's Penance.[3] It has been classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[4]

Arjuna's Penance

Temple

The temple is a small monolithic rock-cut temple with a mandapam dating from the 7th century. Inside the side walls have large sculptured panels depicting Vishnu as Varaha, the boar, holding up Bhudevi, the earth goddess, good examples of naturalistic Pallava art. The Pallava doorkeepers are four pillars that have lion carved into the bases. Inside, on rear wall, is the shrine with guardian figures on either side.[3]

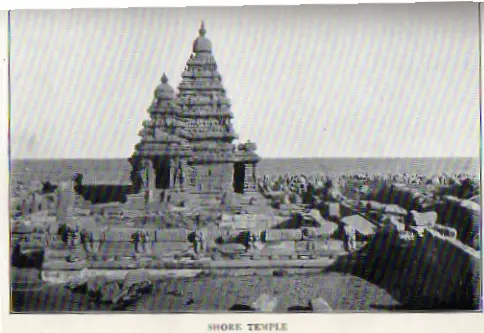

Shore Temple

- The Shore Temple - a structural temple along the Bay of Bengal with the entrance from the western side away from the sea. Recent excavations have revealed new structures here. The temple was reconstructed stone by stone from the sea after being washed away in a cyclone.

The Shore Temple is a structural temple, built with blocks of granites, dating from the 8th century AD build on a promontory sticking out into the Bay of Bengal at Mamallapuram, a tiny village south of Chennai in the state of Tamil Nadu, India. The village was a busy port during the 7th and 8th century reign of the Pallava dynasty. The site is famous for the rock-cut caves and the sculptured rock that line a granite hill, including one depicting Arjuna's Penance as well as for other temples in the area. It has been classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[5]

Architecture

The Shore Temple is a five-storeyed rock cut structural Hindu temple rather than monolithical as are the other monuments at the site. It is the earliest important structural temple in Southern India. Its pyramidal structure is 60 ft high and sits on a 50 ft square platform. There is a small temple in front which was the original porch. [6][7] It is made out of finely cut local granite. [8]

The temple has a garbhagriha in which the deity, Sivalinga, is enshrined, and a small mandapa surrounded by a heavy outer wall with little space between for circumambulation. At the rear are two shrines facing opposite directions. The inner shrine dedicated to Ksatriyasimnesvara is reached through a passage while the other, dedicated to Vishnu, faces the outside. The outer wall of the shrine to Vishnu and the inner side of the boundary wall are extensively sculptured and topped by large sculptures of Nandi.[6]The temple's outer walls are divided by plasters into bays, the lower part being carved into a series of rearing lions.[9] Recent excavations have revealed new structures here under the sand.[10][7]

The Durga is seated on her lion vahana. A small shrine may have been in the cavity in the lion's chest.[7]

Pancha Rathas

- Pancha Rathas (Five Chariots) - five monolithic pyramidal structures named after the Pandavas (Arjuna, Bhima, Yudhishtra, Nakula and Sahadeva) and Draupadi. An interesting aspect of the rathas is that, despite their sizes they are not assembled—each of these is carved from one single large piece of stone.

Underwater city

| Mahabalipuram Tamil Nadu • India | |

| Coordinates: | |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Area • Elevation |

• 12 m (39 ft) |

| District(s) | Kancheepuram |

| Population | 12,049 (2001) |

| Codes • Pincode • Telephone • Vehicle |

• 603104 • +91-44 • TN-21 |

Coordinates:

According to descriptions by early travel writers from Britain, the area near Mahabalipuram had seven pagodas by the sea. Accounts of Mahabalipuram were first written down by British traveller John Goldingham who was told of the "Seven Pagodas" when he visited in 1798.

An ancient port city and parts of a temple built in the 7th century may have been uncovered by the tsunami that resulted from the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. As the waves gradually receded, the force of the water removed sand deposits that had covered various rocky structures and revealed carvings of animals, which included an elaborately carved head of an elephant and a horse in flight. A small square-shaped niche with a carved statue of a deity could be seen above the head of the elephant. In another structure, there was a sculpture of a reclining lion. The use of these animal sculptures as decorations is consistent with other decorated walls and temples from the Pallava period in the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Archaeological Survey of India sent divers to begin underwater excavations of the area on February 17, 2005.

Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram

The Myths

The name “Seven Pagodas” has served as a nickname for the south Indian city of Mahabalipuram, also called Mamallapuram, since the first European explorers reached the city. The phrase “Seven Pagodas” refers to a myth that has circulated in India, Europe, and other parts of the world for over eleven centuries. Mahabalipuram’s Shore Temple, built in the eighth century C.E., stands at the shore of the Bay of Bengal. Legend has it that six other temples once stood with it.

An ancient Brahman legend explains the pagodas’ origins in mythical terms. Prince Hiranyakasipu refused to worship the god Vishnu. The prince’s son, Prahlada, loved Vishnu greatly, and criticized his father’s lack of faith. Hiranyakasipu banished Prahlada, but then relented and allowed him to come home. Father and son quickly began to argue about Vishu’s nature. When Prahlada stated that Vishnu was present everywhere, including in the walls of their home, his father kicked a pillar. Vishnu emerged from the pillar in the form of a man with a lion’s head, and killed Hiranyakasipu. Prahlada eventually became king, and had a son named Bali. Bali founded Mahabalipuram on this site. (Adapted from Coombes, 23-4.)

Unclear ancient evidence

The temples’ origins have been obscured by time, lack of complete written records, and storytelling. Englishman D. R. Fyson, a long-time resident of Madras (now Chennai), wrote a concise book on the city of Mahabalipuram titled Mahabalipuram or Seven Pagodas, which he intended as a souvenir volume for Western visitors to the city. In it, he states that the Pallava King Narasimharavarman I either began or greatly enlarged upon Mahabalipuram, circa 630 C.E. (Fyson 1). Archaeological evidence has not yet clearly proven whether Narasimharavarman I’s city was the earliest to inhabit this location.

About 30 years prior to the founding of Narasimharavarman I’s city, Pallava King Mahendravarman I had begun a series of “cave temples,” which were carved into rocky hillsides (Fyson 2). Contrary to what the name suggests, they often did not begin as natural caves. Mahendravarman I and Narasimharavarman I also ordered construction of free-standing temples, called rathas in the region’s language, Tamil. Nine rathas currently stand at the site (Ramaswami, 209). Construction of both types of temples in Mahabalipuram appears to have ended around 640 C.E. (Fyson 3). Fyson states that archaeological evidence supports the claim that a monastery, or vihara in Tamil, existed in ancient Mahabalipuram. The idea of the monastery would have been adopted from practices of the region’s past Buddhist inhabitants. Fyson suggests that the monks’ quarters may have been divided between a number of the city’s rathas, based on their division into small rooms. Buddhist influence is also apparent in the traditional pagoda shape of the Shore Temple and other remaining architecture (Fyson 5).

Fyson devoted only the next to the last page of his slim book to the actual myth of the Seven Pagodas (Fyson 28). He recounts a local myth regarding the pagodas, that the god Indra became jealous of this earthly city, and sank it during a great storm, leaving only the Shore Temple above water. He also recounts the assertion of local Tamil people that at least some of the other temples can be seen “glittering beneath the waves” from fishing boats (Fyson 28). Whether the six missing pagodas exist does not seem to matter much to Fyson; the Seven Pagodas gave his beloved city its nickname and fame, and that seems to be the important part for him. However the six missing temples have continued to fascinate locals, archaeologists, and lovers of myth alike, and have recently returned to the archaeological spotlight.

European explorers

N. S. Ramaswami names Marco Polo as one of the earliest European visitors to Mahabalipuram. Polo left few details of his visit, but did mark it on his Catalan Map of 1275 (Ramaswami, 210).

Many Europeans later spoke of the Seven Pagodas following travelers to their colonies in India. The first to write of them was John Goldingham, an English astronomer living in Madras in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He wrote an account of his visit and the legend in 1798, which was later collected by Mark William Carr in his 1869 book Descriptive and Historical Papers Relating to the Seven Pagodas on the Coromandel Coast. Goldingham mainly described art, statues, and inscriptions found throughout the archaeological site at Mahabalipuram. He copied many of the inscriptions by hand, and included them in his essay. Goldingham interprets most of the signs as picture-symbols, and discusses what meaning their shapes may have (Goldingham, 30-43). Interestingly, Benjamin Guy Babington, author of another essay in the same volume, identified several of the figures in Goldingham’s copied inscriptions as Telugu letters (Goldingham, 43). Babington’s note on the text is included as a footnote to Goldingham’s work.

In 1914, British writer J.W. Coombes related the common European belief on the origin of the pagoda legend. According to him, the pagodas once stood on the edge of the shore, and their copper domes reflected sunlight and served as a nautical landmark. He claims that modern people do not know for sure how many pagodas once existed. He believes that the number was close to seven (Coombes, 27).

Indian historian N. S. Ramaswami places much of the responsibility for the myth’s European propagation on the poet Robert Southey, who mentioned it in his poem “The Curse of Kehama,” published in 1810 (Ramaswami, 205). He refers to the city by another of its popular names, Bali. In his poem, Southey clearly states that more than one of the Seven Pagodas is visible (See stanza 4). Southey told romantic tales of many cultures around the world, including India, Rome, Portugal, Paraguay, and Native American tribes, all of which were based on accounts of others’ travels, and his own imagination. “The Curse of Kehama” certainly played a role in rising Orientalism.

Ramaswami’s words for European explorers are not entirely negative. He notes that, before Europeans began to visit South India toward the beginning of the Raj, many of the smaller monuments at Mahabalipuram were partially or entirely covered with sand. The colonizers and their families played an important role in uncovering the archaeological site in their free time. Once early English archaeologists realized the extent and beauty of the site, toward the end of the eighteenth century, they appointed experienced antiquarians such as Colin Mackenzie to preside over the dig (Ramaswami, 210).

Missing evidence

Before the tsunami that occurred on December 26, 2004, evidence for the existence of the Seven Pagodas was largely anecdotal. The existence of the Shore Temple, smaller temples, and rathas supported the idea that the area had strong religious significance, but there was little contemporary evidence save one Pallava-era painting of the temple complex. Ramaswami wrote in his 1993 book Temples of South India that evidence of 2000 years of civilization, 40 currently visible monuments, including two “open air bas-reliefs,” and related legends spreading through both South Asia and Europe had caused people to build up Mahabalipuram’s mystery in their minds (Ramaswami, 204). He writes explicitly that “There is no sunk city in the waves off Mamallapuram. The European name, ‘The Seven Pagodas,’ is irrational and cannot be accounted for” (Ramaswami, 206).

Anecdotal evidence can be truthful though, and in 2002 scientists decided to explore the area off the shore of Mahabalipuram, where many modern Tamil fishermen claimed to have glimpsed ruins at the bottom of the sea. This project was a joint effort between the National Institute of Oceanography (India) and the Scientific Exploration Society, U.K (Vora). The two teams found the remains of walls beneath 5 to 8 meters of water and sediment, 500 to 700 meters off the coast. The layout suggested that they belonged to several temples. Archaeologists dated them to the Pallava era, roughly when Mahendravarman I and Narasimharavarman I ruled the region (Vora). NIO scientist K.H. Vora noted after the 2002 exploration that the underwater site probably contained additional structures and artifacts, and merited future exploration (Vora).

During the tsunami

Immediately before the 2004 tsunami struck the Indian Ocean, including the Bay of Bengal, the ocean water off Mahabalipuram’s coast pulled back approximately 500 meters. Tourists and residents who witnessed this event from the beach later recalled seeing a long, straight row of large rocks emerge from the water (Subramanian). As the tsunami rushed to shore, these stones were covered again by water. However, centuries’ worth of sediment that had covered them was gone. The tsunami also made some immediate, lasting changes to the coastline, which left a few previously covered statues and small structures uncovered on the shore (Maguire).

After the tsunami

Eyewitness accounts of tsunami relics stirred both popular and scientific interest in the site. Perhaps the most famous archaeological finding after the tsunami was a large stone lion, which the changing shoreline left sitting uncovered on Mahabalipuram’s beach. Archaeologists have dated it to the 7th century A.D (“India finds more…”). Locals and tourists have flocked to see this statue since shortly after the tsunami.

In April 2005, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and the Indian Navy began searching the waters off the coast of Mahabalipuram by boat, using sonar technology (Das). They discovered that the row of large stones people had seen immediately before the tsunami were part of a 6-foot-high (Biswas), 70-meter-long wall (Subramanian). ASI and the Navy also discovered remains of two other submerged temples and one cave temple within 500 meters of the shore (Das). Although these findings do not necessarily correspond to the seven pagodas of myth, they do indicate that a large complex of temples was located in Mahabalipuram. This draws the myth closer to reality—and there are likely many more discoveries waiting to be found.

ASI archaeologist Alok Tripathi told The Times of India that, as of his February 2005 interview, sonar exploration had mapped inner and outer walls of the two previously submerged temples. He explained that his team could not yet suggest the functions of these buildings (Das). A.K. Sharma of the Indian Navy could not provide further speculation as to function either, but told The Times of India that the layout of the submerged structures, in relation with the Shore Temple and other exposed structures, closely matched a Pallava-era painting of the Seven Pagodas complex (Das).

Archaeologist T. Satyamurthy of ASI also mentions the great significance of a large inscribed stone the waves uncovered. The inscription stated that King Krishna III had paid for the keeping of an eternal flame at a particular temple. Archaeologists began digging in the vicinity of the stone, and quickly found the structure of another Pallava temple. They also found many coins and items that would have been used in ancient Hindu religious ceremonies (Maguire). While excavating this Pallava-era temple, archaeologists also uncovered the foundations of a Tamil Sangam-period temple, dating back approximately 2000 years (Maguire). Most archaeologists working on the site believe that a tsunami struck sometime between the Tamil Sangam and Pallava periods, destroying the older temple. Wide-spread layers of seashells and other ocean debris support this theory (Maguire).

ASI also unexpectedly located a much older structure on the site. A small brick structure, formerly covered by sand, stood on the beach following the tsunami. Archaeologists examined the structure, and dated it to the Tamil Sangam period (Maguire). Although this structure does not necessarily fit in with the traditional legend, it adds intrigue and the possibility of yet-unexplored history to the site.

The current opinion among archaeologists is that yet another tsunami destroyed the Pallava temples in the 13th century. ASI scientist G. Thirumoorthy told the BBC that physical evidence of a 13th century tsunami can be found along nearly the entire length of India’s East Coast (Maguire).

Is the myth true?

Twenty-first century probes of the coast off Mahabalipuram have not yet conclusively proven the truth of the Seven Pagodas myth. They do bring archaeologists and historians closer to believing in the myth. As exploration continues, we will come closer to knowing the reality behind the pagodas.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Application of Geological and Geophysical Methods in Marine Archaeology and Underwater Explorations. Scientific Achievements: 5. Tamil Nadu. K H. Vora. National Institute of Oceanography, Goa, India. 16 Sep. 2006 <http://www.nio.org/projects/vora/project_vora_5.jsp>.

- Biswas, Soutik. "Tsunami Throws up India Relics." BBC News (Online) 11 Feb. 2005. Retrieval 16 Sep. 2006 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4257181.stm>.

- Coombes, J.W. (Josiah Waters). The Seven Pagodas. London, UK: Selley, Service & Co., Ltd., 1914.

- Das, Swati. "Tsunami Unveils 'Seven Pagodas'." The Times of India 25 Feb. 2005. Retrieval 12 Sep. 2006 <http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/1032004.cms>.

- Fyson, D. R. Mahabalipuram or Seven Pagodas. Madras, Tamil Nadu, India: Higginbothams, Publishers, 1931.

- Goldingham, J. “Some account of the Sculptures at Mahabalipuram; usually called the Seven Pagodas.” Descriptive and Historical Papers Relating to The Seven Pagodas on the Coromandel Coast. Ed. Mark William Carr. New Delhi, India: Asian Educational Services, 1984. Reprinted from the original 1869 edition.

- "India Finds More 'Tsunami Gifts'." From staff reports. BBC News (Online) 27 Feb. 2005: 1-5. . . Retrieval 16 Sep. 2006 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4302115.stm>.

- Maguire, Paddy. "Tsunami Reveals Ancient Temple Sites." BBC News (Online) 27 Oct. 2005. Retrieval 9 Sep. 2006 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4312024.stm>.

- Ramaswami, N. S. Temples of South India. Madras, Tamil Nadu, India: Maps and Agencies, 1993.

- Schulberg, Lucille and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Historic India. Series: Great Ages of Man, a History of the World's Cultures. New York, NY: Time-Life Books, 1968.

- Subramanian, T. S. "The Secret of the Seven Pagodas." Frontline 22.10 (May 2005). The Hindu Online. 16 Sep. 2006 <http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl2210/stories/20050520005812900.htm>.

Gallery

See also

- Undavalli caves

- Badami Cave Temples

- Kanheri Caves

- Indian rock-cut architecture

External links

- Photo of Varsha Cave Temple exterior

- Photo Varaha sculpture example

- Cave Biology (Biospeleology)Solutions for India's Cave related queries

- Photo of inside of shrine

- Varasha Caves

References

External links

- Mahabalipuram

- Travel guide to Mahabalipuram from Wikitravel

- Mahabalipuram in UNESCO List

- Arjuna's Penance

- `I show you Mahabalipuram'

- National Institute of Oceanography: Mahabalipuram and Poompuhar

- Archaeological Survey of India site on Mahabalipuram

- Sea level falls after tsunami

- The Shore Temple stands its ground T.S. Subramanian in The Hindu, 30 December 2004

- Newly-discovered Mahabalipuramtemple fascinates archaeologists T.S. Subramanian in The Hindu, 10 April 2005

- Mahabalipuram Temple Architecture

- Mahabalipuram Photos from india-picture.net

- The India Atlantis Expedition - March 2002

- Read Useful Details about Mahabalipuram Temple

- Tsunami's might opens way for science (The Globe and Mail; February 18, 2005)

- BBC News: India finds more 'tsunami gifts'

- Inscriptions of India—Complete listing of historical inscriptions from Indian temples and monuments

- Photographs of Mahabalipuram and other sites in Tamil Nadu

- A videograph of Mahabalipuram in HD

- About Thirukadalmallai

- About Sthalasayana Perumal Temple

- DivyaDesam

- Photos of the site

See also

- Arjuna's Penance

- Varaha Cave Temple

- Shore Temple

- Pancha Rathas

| |||||||

Notes

- ↑ Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ↑ The Descent of the Ganges - Story of Bhagirata. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 General view of the entrance to the Varaha Cave Temple, Mamallapuram. British Library. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram. World Heritage. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram. World Heritage. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Shore Temple. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Shore Temple. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions, p 51. ISBN 0794600115.

- ↑ Michael, George (1988). The Hindu Temple. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago, pp 134-135. ISBN 0226532305.

- ↑ The Shore Temple stands its ground. The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Mahabalipuram history

- Thirukadalmallai history

- Descent_of_the_Ganges_(Mahabalipuram) history

- 172855070 history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.