Difference between revisions of "Jewelry" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Image:amber.pendants.800pix.050203.jpg|thumb|right|[[Amber]] jewelry in the form of pendants]] | [[Image:amber.pendants.800pix.050203.jpg|thumb|right|[[Amber]] jewelry in the form of pendants]] | ||

| − | '''Jewelry''' | + | '''Jewelry''' is a personal [[ornament]], such as a necklace, ring, or bracelet, made from [[gemstone|gemstones]], [[precious metal]]s or other substances. The word jewellery is derived from the word jewel, which was anglicised from the Old French "jouel" around the 13th century and traces back to the Latin word "jocale", meaning plaything..<ref>[http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/jewel jewel. (n.d.).] Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved August 7, 2007, from Dictionary.com website.</ref> Whether as currency, protection, or fashion, jewelry is one of the oldest forms of body adornment, the most ancient example found being 82,000 years old.<ref name="bbcnewsdiscovery">[[22 June]] [[2006]]. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5099104.stm Study reveals 'oldest jewellery']. BBC News.</ref> Either way, jewelry as been appreciated for its rarity, beauty, and artistic quality. |

| − | |||

==Form and function== | ==Form and function== | ||

Revision as of 18:59, 20 December 2007

Jewelry is a personal ornament, such as a necklace, ring, or bracelet, made from gemstones, precious metals or other substances. The word jewellery is derived from the word jewel, which was anglicised from the Old French "jouel" around the 13th century and traces back to the Latin word "jocale", meaning plaything..[1] Whether as currency, protection, or fashion, jewelry is one of the oldest forms of body adornment, the most ancient example found being 82,000 years old.[2] Either way, jewelry as been appreciated for its rarity, beauty, and artistic quality.

Form and function

Jewelry has been used for a number of reasons:

- Currency, wealth display and storage,

- Functional use (such as clasps, pins, and buckles)

- Symbolism (to show membership or status)

- Protection (in the form of amulets and magical wards),[3]

- Artistic display

Although during earlier times jewelry was created for practical uses such as wealth storage and pinning clothes together, in recent times it has been used almost exclusively for decoration. The first pieces of jewelry were made from natural materials, such as bone, animal teeth, shell, wood, and carved stone. Jewelry was often made for people of high importance to show their status and, in many cases, they were buried with it.

Most cultures have at some point had a practice of keeping large amounts of wealth stored in the form of jewelry. Numerous cultures move wedding dowries in the form of jewelry, or create jewelry as a means to store or display coins. Alternatively, jewelry has been used as a currency or trade good; an example being the use of slave beads.[citation needed]

Many items of jewelry, such as brooches and buckles originated as purely functional items, but evolved into decorative items as their functional requirement diminished.[4]

Jewelry can also be symbolic of group membership, as in the case of the Christian crucifix or Jewish Star of David, or of status, as in the case of chains of office, or the Western practice of married people wearing a wedding ring.

Wearing of amulets and devotional medals to provide protection or ward off evil is common in some cultures; these may take the form of symbols (such as the ankh), stones, plants, animals, body parts (such as the Khamsa), or glyphs (such as stylized versions of the Throne Verse in Islamic art).[5]

Although artistic display has clearly been a function of jewelry from the very beginning, the other roles described above tended to take primacy.[citation needed] It was only in the late 19th century, with the work of such masters as Peter Carl Fabergé and René Lalique, that art began to take primacy over function and wealth.[citation needed] This trend has continued into modern times, expanded upon by artists such as Robert Lee Morris and Ed Levin.

Materials and methods

In creating jewelry, gemstones, coins, or other precious items are often used, and they are typically set into precious metals. Alloys of nearly every metal known have been encountered in jewellery—bronze, for example, was common in Roman times. Modern fine jewelry usually includes gold, white gold, platinum, palladium, or silver. Most American and European gold jewelry is made of an alloy of gold, the purity of which is stated in karats, indicated by a number followed by the letter K. American gold jewelry must be of at least 10K purity (41.7% pure gold), (though in England the number is 9K (37.5% pure gold) and is typically found up to 18K (75% pure gold). Higher purity levels are less common with alloys at 22 K (91.6% pure gold), and 24 K (99.9% pure gold) being considered too soft for jewelry use in America and Europe. These high purity alloys, however, are widely used across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.[citation needed] Platinum alloys range from 900 (90% pure) to 950 (95.0% pure). The silver used in jewelry is usually sterling silver, or 92.5% fine silver. In costume jewelry, stainless steel findings are sometimes used.

Other commonly used materials include glass, such as fused-glass or enamel; wood, often carved or turned; shells and other natural animal substances such as bone and ivory; natural clay; polymer clay; and even plastics. However, any inclusion of lead or lead solder will cause an English Assay office (the building which gives English jewelry its stamp of approval, the Hallmark) to destroy the piece. [citation needed]

Beads are frequently used in jewelry. These may be made of glass, gemstones, metal, wood, shells, clay and polymer clay. Beaded jewelry commonly encompasses necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and belts. Beads may be large or small, the smallest type of beads used are known as seed beads, these are the beads used for the "woven" style of beaded jewelry. Another use of seed beads is an embroidery technique where seed beads are sewn onto fabric backings to create broad collar neck pieces and beaded bracelets. Bead embroidery, a popular type of handwork during the Victorian era is enjoying a renaissance in modern jewelry making.

Advanced glass and glass beadmaking techniques by Murano and Venetian glassmasters developed crystalline glass, enameled glass (smalto), glass with threads of gold (goldstone), multicoloured glass (millefiori), milk-glass (lattimo) and imitation gemstones made of glass.[citation needed] As early as the 13th century, Murano glass and Murano beads were popular.[citation needed]

Silversmiths, goldsmiths, and lapidaries methods include forging, casting, soldering or welding, cutting, carving, and "cold-joining" (using adhesives, staples, and rivets to assemble parts).[6]

History

The history of jewelry is a long one, with many different uses among different cultures. It has endured for thousands of years and has provided various insights into how ancient cultures worked.

The first signs of jewelry came from the Cro-Magnons, ancestors of Homo sapiens, around 40,000 years ago. The Cro-Magnons originally migrated from the Middle East to settle in Europe and replace the Neanderthals as the dominant species. The jewelry pieces they made were crude necklaces and bracelets of bone, teeth and stone hung on pieces of string or animal sinew, or pieces of carved bone used to secure clothing together. In some cases, jewelry had shell or mother-of-pearl pieces. In southern Russia, carved bracelets made of mammoth tusk have been found. Most commonly, these have been found as grave-goods. Around 7,000 years ago, the first sign of copper jewelry was seen.[4]

Rome

Although jewelry work was abundantly diverse in earlier times, especially among the barbarian tribes such as the Celts, when the Romans conquered most of Europe, jewelry was changed as smaller factions developed the Roman designs. The most common artifact of early Rome was the brooch, which was used to secure clothing together. The Romans used a diverse range of materials for their jewelry from their extensive resources across the continent. Although they used gold, they sometimes used bronze or bone and in earlier times, glass beads & pearl. As early as 2,000 years ago, they imported Sri Lankan sapphires and Indian diamonds and used emeralds and amber in their jewelry. In Roman-ruled England, fossilized wood called jet from Northern England was often carved into pieces of jewelry. The early Italians worked in crude gold and created clasps, necklaces, earrings and bracelets. They also produced larger pendants which could be filled with perfume.

Like the Greeks, often the purpose of Roman jewelry was to ward off the “Evil Eye” given by other people. Although woman wore a vast array of jewelry, men often only wore a finger ring. Although they were expected to wear at least one ring, some Roman men wore a ring on every finger, while others wore none. Roman men and women wore rings with a carved stone on it that was used with wax to seal documents, an act that continued into medieval times when kings and noblemen used the same method. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the jewelry designs were absorbed by neighboring countries and tribes.[7]

Middle Ages

Post-Roman Europe continued to develop jewelry making skills; the Celts and Merovingians in particular are noted for their jewelry, which in terms of quality matched or exceeded that of Byzantium. Clothing fasteners, amulets, and to a lesser extent signet rings are the most common artefacts known to us; a particularly striking celtic example is the Tara Brooch. The Torc was common throughout Europe as a symbol of status and power. By the 8th century, jewelled weaponry was common for men, while other jewelry (with the exception of signet rings) seems to become the domain of women. Grave goods found in a 6th-7th century burial near Chalon-sur-Saône are illustrative; the young girl was buried with: 2 silver fibulae, a necklace (with coins), bracelet, gold earrings, a pair of hair-pins, comb, and buckle.[8] The Celts specialized in continuous patterns and designs; while Merovingian designs are best known for stylized animal figures.[9] They were not the only groups known for high quality work; note the Visigoth work shown here, and the numerous decorative objects found at the Anglo-Saxon Ship burial at Sutton Hoo Suffolk, England, are a particularly well-known example.[7] On the continent, cloisonné and garnet were perhaps the quintessential method and gemstone of the period.

The Eastern successor of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, continued many of the methods of the Romans, though religious themes came to predominate. Unlike the Romans, the Franks, and the Celts, however; Byzantium used light-weight gold leaf rather than solid gold, and more emphasis was placed on stones and gems. As in the West, Byzantine jewelry was worn by wealthier females, with male jewelry apparently restricted to signet rings.

Like other contemporary cultures, jewelry was commonly buried with its owner.[10]

Renaissance

The Renaissance and exploration both had significant impacts on the development of jewelry in Europe. By the 17th century, increasing exploration and trade lead to increased availability of a wide variety of gemstones as well as exposure to the art of other cultures. Whereas prior to this the working of gold and precious metal had been at the forefront of jewelry, this period saw increasing dominance of gemstones and their settings. A fascinating example of this is the Cheapside Hoard, the stock of a jeweller hidden in London England during the Commonwealth period and not found again until 1912. It contained Colombian emerald, topaz, amazonite from Brazil, spinel, iolite, and chrysoberyl from Sri Lanka, ruby from India, Afghani lapis lazuli, Persian turquoise, Red Sea peridot, as well as Bohemian and Hungarian opal, garnet, and amethyst. Large stones were frequently set in box-bezels on enamelled rings.[11] Notable among merchants of the period was Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who in the 1660s brought the precursor stone of the Hope Diamond to France.

When Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned as Emperor of the French in 1804, he revived the style and grandeur of jewelry and fashion in France. Under Napoleon’s rule, jewelers introduced parures, suites of matching jewelry, such as a diamond tiara, diamond earrings, diamond rings, a diamond brooch and a diamond necklace. Both of Napoleon’s wives had beautiful sets such as these and wore them regularly. Another fashion trend resurrected by Napoleon was the cameo. Soon after his cameo decorated crown was seen, cameos were highly sought after. The period also saw the early stages of costume jewelry, with fish scale covered glass beads in place of pearls or conch shell cameos instead of stone cameos. New terms were coined to differentiate the arts: jewelers who worked in cheaper materials were called bijoutiers, while jewelers who worked with expensive materials were called joailliers; a practice which continues to this day.

Romanticism

Starting in the late 18th century, Romanticism had a profound impact on the development of western jewelry. Perhaps the most significant influences were the public’s fascination with the treasures being discovered through the birth of modern archaeology, and the fascination with Medieval and Renaissance art. Changing social conditions and the onset of the industrial revolution also lead to growth of a middle class that wanted and could afford jewelry. As a result, the use of industrial processes, cheaper alloys, and stone substitutes, lead to the development of paste or costume jewelry. Distinguished goldsmiths continued to flourish, however, as wealthier patrons sought to ensure that what they wore still stood apart from the jewelry of the masses, not only through use of precious metals and stones but also though superior artistic and technical work; one such artist was the French goldsmith Françoise Désire Fromment Meurice. A category unique to this period and quite appropriate to the philosophy of romanticism was mourning jewelry. It originated in England, where Queen Victoria was often seen wearing jet jewelry after the death of Prince Albert; and allowed the wearer to continue wearing jewelry while expressing a state of mourning at the death of a loved one.[12]

In the United states, this period saw the founding in 1837 of Tiffany & Co. by Charles Lewis Tiffany. Tiffany's put the United States on the world map in terms of jewelry, and gained fame creating dazzling commissions for people such as the wife of Abraham Lincoln; later it would gain popular notoriety as the setting of the film Breakfast at Tiffany's. In France, Pierre Cartier founded Cartier SA in 1847, while 1884 saw the founding of Bulgari in Italy. The modern production studio had been born; a step away from the former dominance of individual craftsmen and patronage.

This period also saw the first major collaboration between East and West; collaboration in Pforzheim between German and Japanese artists lead to Shakudo plaques set into Filigree frames being created by the Stoeffler firm in 1885).[13] Perhaps the grand finalé – and an appropriate transition to the following period – were the masterful creations of the Russian artist Peter Carl Fabergé, working for the Imperial Russian court, whose Fabergé eggs and jewelry pieces are still considered as the epitome of the goldsmith’s art.

Art Nouveau

In the 1890s, jewelers began to explore the potentials of the growing Art Nouveau style. Very closely related were the German Jugendstil, British (and to some extent American) Arts and Crafts movement. René Lalique, working for the Paris shop of Samuel Bing, was recognized by contemporaries as a leading figure in this trend. The Darmstadt Artists' Colony and Wiener Werkstaette provided perhaps the most significant German input to the trend, while in Denmark Georg Jensen, though best known for his Silverware, also contributed significant pieces. In England, Liberty & Co and the British arts & crafts movement of Charles Robert Ashbee contributed slightly more linear but still characteristic designs. The new style moved the focus of the jeweller's art from the setting of stones to the artistic design of the piece itself; Lalique's famous dragonfly design is one of the best examples of this. Enamels played a large role in technique, while sinuous organic lines are the most recognizable design feature. The end of World War One once again changed public attitudes; and a more sober style was set to take centre-stage.[14]

Art Deco

Growing political tensions, the after-effects of the war, and a general reaction against the perceived decadence of the turn of the century led to simpler forms, combined with more effective manufacturing for mass production of high-quality jewelry. Covering the period of the 1920s and 1930s, the style has become popularly known as Art Deco. Walter Gropius and the German Bauhaus movement, with their philosophy of "no barriers between artists and craftsmen" lead to some interesting and stylistically simplified forms. Modern materials were also introduced: plastics and aluminum were first used in jewelry, and of note are the chromed pendants of Russian born Bauhaus master Naum Slutzky. Technical mastery became as valued as the material itself; in the west, this period saw the reinvention of granulation by the German Elizabeth Treskow (although development of the re-invention has continued into the 1990s)..

Modern

Modern jewelry has never been as diverse as it is in the present day. The modern jewelry movement began in the late 1940s at the end of World War II with a renewed interest in artistic and leisurely pursuits. The movement is most noted with works by Georg Jensen and other jewelry designers who advanced the concept of wearable art. The advent of new materials, such as plastics, Precious Metal Clay (PMC) and different colouring techniques, has led to increased variety in styles. Other advances, such as the development of improved pearl harvesting by people such as Kokichi Mikimoto and the development of improved quality artificial gemstones such as moissanite (a diamond simulant), has placed jewelry within the economic grasp of a much larger segment of the population. The "jewelry as art" movement, spearheaded by artisans such as Robert Lee Morris and continued by designers such as Anoush Waddington in the UK, has kept jewelry on the leading edge of artistic design. Influence from other cultural forms is also evident; one example of this is bling-bling style jewelry, popularized by hip-hop and rap artists in the early 21st century. With the world's designs more accessible to jewelers, designs have blended in aspects from many different cultures from many different periods in time.

The late 20th century saw the blending of European design with oriental techniques such as Mokume-gane. The following are noted as the primary innovations in the decades stadling the year 2000: "Mokume-gane, hydraulic die forming, anti-clastic raising, fold-forming, reactive metal anodizing, shell forms, PMC, photoetching, and [use of] CAD/CAM."[15]

Artisan jewelry continues to grow as both a hobby and a profession. With more than 17 U.S. periodicals about beading alone, resources, accessibility and a low initial cost of entry continues to expand production of hand-made adornments. Popular because of its uniqueness, artisan jewelry can be found in just about any price range. Some fine examples of artisan jewelry can be seen at The Metropolitan Museum.[16]

Body modification

It can be difficult to determine where jewelry leaves off and body modification takes over, because they are different sub-categories of body art. For the most part, jewelry used in body modification is plain; the use of simple silver studs, rings and earrings predominates. In fact, common jewelry pieces such as earrings, are themselves a form of body modification, as they are accommodated by creating a small hole in the human ear.

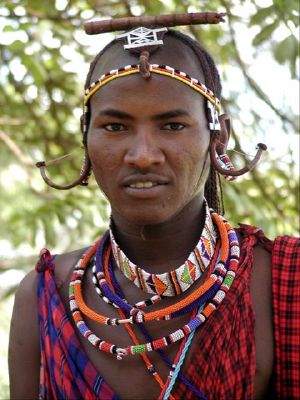

Padaung women in Myanmar place large golden rings around their necks. From as early as 5 years old, girls are introduced to their first neck ring. Over the years, more rings are added. In addition to the twenty-plus pounds of rings on her neck, a woman will also wear just as many rings on her calves too. At their extent, some necks modified like this can reach 10-15 inches long; the practice has obvious health impacts, however, and has in recent years declined from cultural norm to tourist curiosity.[17] Tribes related to the Paduang, as well as other cultures throughout the world, use jewelry to stretch their earlobes, or enlarge ear piercings. In the Americas, labrets have been worn since before first contact by innu and first nations peoples of the northwest coast.[18] Lip plates are worn by the African Mursi and Sara people, as well as some South American peoples.

In the late 20th century, the influence of modern primitivism led to many of these practices being incorporated into western subcultures. Many of these practices rely on a combination of body modification and decorative objects; thus keeping the distinction between these two types of decoration blurred. As with other forms of jewelry, the crossing of cultural boundaries is one of the more significant features of the artform in the early 21st century.

In many cultures, jewelry is used as a temporary body modifier, with in some cases, hooks or even objects as large as bike bars being placed into the recipient's skin. Although this procedure is often carried out by tribal or semi-tribal groups, often acting under a trance during religious ceremonies, this practice has seeped into western culture. Many extreme-jewelry shops now cater to people wanting large hooks or spikes set into their skin. Most often, these hooks are used in conjunction with pulleys to hoist the recipient into the air. This practice is said to give an erotic feeling to the person and some couples have even performed their marriage ceremony whist being suspended by hooks.[17]

See also

| Gemology and Jewelry Portal |

Notes

- ↑ jewel. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved August 7, 2007, from Dictionary.com website.

- ↑ 22 June 2006. Study reveals 'oldest jewellery'. BBC News.

- ↑ Kunz, PhD, DSc, George Frederick (1917). Magic of Jewels and Charms. John Lippincott Co.. URL: Magic Of jewels: Chapter VII Amulets George Frederick Kunz was gemmologist for Tiffany's built the collections of banker J.P. Morgan and the American Natural History Museum in NY City. This chapter deals entirely with using jewels and gemstones in jewelry for talismanic purposes in Western Cultures. The next chapter deals with other, indigenous cultures. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Holland, J. 1999. The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia. Kingfisher books. Retrieved December 18, 2007. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "kingfisherhistory" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Morris, Desmond. Body Guards: Protective Amulets and Charms. Element, 1999 ISBN 1-86204-572-0. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ McCreight, Tim. Jewelry: Fundamentals of Metalsmithing. Design Books International, 1997 ISBN 1-880140-29-2. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Reader's Digest Association. 1986. The last 2 million years. Reader's Digest. ISBN 0-86438-007-0. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Duby Georges and Philippe Ariès, eds. A History of Private Life Vol 1 - From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Harvard, 1987. p 506. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Duby, throughout. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Sherrard, P. 1972. Great Ages of Man: Byzantium. Time-Life International. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Scarisbrick, Diana. Rings: Symbols of Wealth, Power, and Affection. New York: Abrams, 1993. ISBN 0-8109-3775-1 p77. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Farndon, J. 2001. 1,000 Facts on Modern History. Miles Kelly Publishing. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Ilse-Neuman, Ursula. Book review “Schmuck/Jewelry 1840-1940: Highlights from the Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim.’’ ‘’Metalsmith’’. Fall2006, Vol. 26 Issue 3, p12-13, 2p. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Constantino, Maria. Art Nouveau. Knickerbocker Press; 1999 ISBN 1-57715-074-0 as well as Ilse-Neuman 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ McCrieght, Tim. "What's New?" Metalsmith Spring 2006, Vol. 26 Issue 1, p42-45, 4p. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ajew/hd_ajew.htm. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Packard, M. 2002. Ripley's Believe it or not: Special Edition. Scholastic Inc. 22. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Moss, Madonna L. "George Catlin among the Nayas: Understanding the practice of labret wearing on the Northwest Coast." Ethnohistory Winter99, Vol. 46 Issue 1, p31, 35p. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Borel, F. 1994. The Splendor of Ethnic Jewelry: from the Colette and Jean-Pierre Ghysels Collection. New York: H.N. Abrams. (ISBN 0-8109-2993-7).

- Evans, J. 1989. A History of Jewelry 1100-1870. (ISBN 0-486-26122-0).

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea 1998. Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. (ISBN 0-313-29497-6).

- Tait, H. 1986. Seven Thousand Years of Jewelry. London: British Museum Publications. (ISBN 0-7141-2034-0).

External links

- History of Jewelry. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- Glossary of Jewelry terms. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- Ancient Jewelry from Central Asia (IV BC-IV AD). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.