Difference between revisions of "Hathor" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove date links) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Image:Egypt.Hathor.jpg|thumb|right|160px|Statue of Hathor (Luxor Museum)]] | [[Image:Egypt.Hathor.jpg|thumb|right|160px|Statue of Hathor (Luxor Museum)]] | ||

| + | In [[Egyptian mythology]], '''Hathor''' ([[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] for ''house of [[Horus]]'') was originally a personification of the [[Milky Way]], which was seen as the milk that flowed from the [[udder]]s of a heavenly [[cow]]. Hathor was an ancient goddess, and was worshipped as a cow-deity from at least [[2700 B.C.E.]],[http://www.hethert.org/ladyofthewest.html] during the [[Second dynasty of Egypt|second dynasty]]. Her worship the Egyptians goes back earlier however, possibly, even by the [[King Scorpion|Scorpion King]] who ruled during the [[Protodynastic Period of Egypt|Protodynastic Period]] before the dynasties began. His name, Serqet, may refer to the goddess [[Serket]]. | ||

| − | + | The name ''Hathor'' refers to the encirclement by her, in the form of the [[Milky Way]], of the night sky and consequently of the god of the sky, [[Horus]] who was said to be her son. Later she was described as the wife of [[Ra]], the creator whose own cosmic birth was formalised in the [[Ogdoad]] [[cosmogeny]] after his worship arose and displaced that of Horus. At that time images of Ra bear the [[eye of Ra|eye]] motif. | |

| − | An alternate name for | + | An alternate name for Hathor, which persisted for 3,000 years, was '''Mehturt''' (also spelt '''Mehurt''', '''Mehet-Weret''', and '''Mehet-uret'''), meaning ''great flood'', a direct reference to her being the milky way.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

| − | + | The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and the king, leading the ancient [[Egyptians]] to describe it as ''The Nile in the Sky''. Due to this, and the name ''mehturt'', she was identified as responsible for the yearly inundation of the [[Nile]]. | |

| − | + | Another consequence of this name is that she was seen as a herald of imminent birth, as when the [[amniotic sac]] breaks and floods its waters, it is a medical indicator that the child is due to be born extremely soon. | |

| − | == | + | Another interpretation of the Milky Way was that it was the primal snake, [[Wadjet]], the protector of Egypt who was closely associated with Hathor and other early deities among the various aspects of the great mother goddess, including [[Mut]] and [[Naunet]]. |

| + | |||

| + | Hathor also was favoured as a protector in desert regions (see [[Serabit el-Khadim]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Hathor in an Egyptian Context== | ||

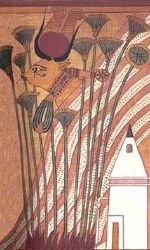

| + | [[Image:Hathor with sacred eye in papyrus.JPG|thumb|150px|right|Hathor as a cow, wearing her necklace and showing her sacred eye - [[Papyrus of Ani]]]] | ||

| + | As an Egyptian deity, Hathor belonged to a religious, mythological and cosmological belief system that developed in the [[Nile]] river basin from earliest prehistory to around 525 B.C.E.<ref>This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.</ref> Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.<ref>The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).</ref> The cults were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.<ref>These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).</ref> Yet, the Egyptian gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “If we compare two of [the Egyptian gods] … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”<ref>Frankfort, 25-26.</ref> One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanent—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.<ref>Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.</ref> Thus, those Egyptian gods who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Furthermore, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of [[Amun-Re]], which unified the domains of [[Amun]] and [[Re]]), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.<ref>Frankfort, 20-21.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely defined by the geographical and calendrical realities of its believers' lives. The Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.<ref>Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).</ref> The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.<ref>Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.</ref> Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Milky Way personified == | ||

| + | [[Image:Deathvalleysky nps big.jpg|thumb|center|700px|The Milky Way seen in a wide angle photograph from a remote, unlit area.]] | ||

| + | Few contemporary human cultures live without illumination at night that blocks the nighttime sky, some could not describe the Milky Way and the stars that dominated the nights of these people and their imaginations. It is a hazy band of white light that is seen in the night sky, arching across the entire celestial sphere. Anthropologists presume that legends built around the aspects of the sky and other natural phenomenon became the traditions upon which the myths were described while viewing the sky. Associations with the deities exists in all cultures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Egypt the primordial waters were associated with the Nile River which often flooded the land, both feared and bountiful. The Milky Way often was described as the river in the sky in Egyptian texts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Associations, images, and symbols == | ||

[[Image:Egypt.Dendera.Hathor.01.jpg|thumbnail|left|[[Dendera Temple complex|Dendera Temple]], showing Hathor on the capitals of a column]] | [[Image:Egypt.Dendera.Hathor.01.jpg|thumbnail|left|[[Dendera Temple complex|Dendera Temple]], showing Hathor on the capitals of a column]] | ||

| + | Eventually, Hathor's identity as a [[cow]], meant that she became identified with another ancient cow-goddess of fertility, [[Bat (goddess)|Bat]]. It still remains an unanswered question amongst [[egyptology|Egyptologists]] as to why Bat survived as an independent goddess for so long. Bat was, in some respects, connected to the [[Egyptian soul|Ba]], an aspect of the soul, and so Hathor gained an association with the [[Duat|afterlife]]. It was said that, with her motherly character, she greeted the souls of the dead in Duat, and proffered them with refreshments of food and drink. She also was described sometimes as ''mistress of the [[acropolis]]''. | ||

| − | + | The assimilation of Bat, who was associated with the [[sistrum]], a musical instrument, brought with it an association with music. In this form, Hathor's cult became centred in [[Dendera]] and was led by priests who also were [[dance]]rs, [[song|singers]], and other entertainers. | |

| − | + | [[Image:GD-EG-Caire-Musée091.JPG|300px|thumb|Sculpture of Hathor as a cow, with all of her symbols, the sun disk, the cobra, as well as her necklace and crown]] | |

| + | Hathor also became associated with the [[menat]], the [[turquoise]] ''musical [[necklace]]'' often worn by women. A hymn to Hathor says: | ||

:''Thou art the Mistress of Jubilation, the Queen of the Dance, the Mistress of Music, the Queen of the Harp Playing, the Lady of the Choral Dance, the Queen of Wreath Weaving, the Mistress of Inebriety Without End''. | :''Thou art the Mistress of Jubilation, the Queen of the Dance, the Mistress of Music, the Queen of the Harp Playing, the Lady of the Choral Dance, the Queen of Wreath Weaving, the Mistress of Inebriety Without End''. | ||

| − | Essentially, Hathor had become a goddess of Joy, and so she was deeply loved by the general population, and truly revered by women, who aspired to embody her multifaceted role as wife, mother, and lover. In this capacity, she gained the titles of ''Lady of the House of Jubilation'', and ''The One Who Fills the Sanctuary with Joy''. The worship of Hathor was so popular that more festivals were dedicated to her honour than any other Egyptian deity, and more children were named after this goddess than any other. Even Hathor's priesthood was unusual, in that both men and women became her priests. | + | Essentially, Hathor had become a goddess of Joy, and so she was deeply loved by the general population, and truly revered by women, who aspired to embody her multifaceted role as wife, mother, and lover. In this capacity, she gained the titles of ''Lady of the House of Jubilation'', and ''The One Who Fills the Sanctuary with Joy''. |

| + | |||

| + | The worship of Hathor was so popular that more festivals were dedicated to her honour than any other Egyptian deity, and more children were named after this goddess than any other. Even Hathor's priesthood was unusual, in that both men and women became her priests. | ||

== Bloodthirsty warrior ==<!-- This section is linked from [[Sechat-Hor]] —> | == Bloodthirsty warrior ==<!-- This section is linked from [[Sechat-Hor]] —> | ||

| + | [[Image:Egypt.KV43.01.jpg|thumb|left|Hathor among the deities greeting the newly dead pharaoh, Thutmose IV, from his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Luxor, Egypt]] | ||

| + | The [[Middle Kingdom of Egypt|Middle Kingdom]] was founded when [[Upper Egypt]]'s pharaoh, [[Mentuhotep II]], took control over [[Lower Egypt]], which had become independent during the [[First Intermediate Period]] by force. This unification had been achieved by a brutal war that was to last some twenty-eight years with many casualties, but when it ceased, calm returned, and the reign of the next pharaoh, [[Mentuhotep III]], was peaceful, and Egypt once again became prosperous. A tale, from the perspective of Lower Egypt, developed around this experience of protracted war. | ||

| − | + | In the tale following the war, Ra (representing the pharaoh of Upper Egypt) was no longer respected by the people (of Lower Egypt) and they ceased to obey his authority, which made him so angry that he sent out [[Sekhmet]] (war goddess of Upper Egypt) to destroy them. Sekhmet became bloodthirsty and the slaughter was great because she could not be stopped. As the slaughter continued, fear that all of humanity would be destroyed arose among the deities and Ra was charged with stopping her. Ra poured huge quantities of blood-coloured beer on the ground to trick Sekhmet. She drank so much of it—thinking it to be blood—that she became too drunk to continue the slaughter and humanity was saved. Afterward Sekhmet became loving and kind. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The form that Sekhmet had become by the end of the tale was identical in character to Hathor, and so a cult arose, at the start of the Middle Kingdom, which dualistically identified Sekhmet with Hathor, making them one goddess, ''Sekhmet-Hathor'', with two sides. Consequently, Hathor, as Sekhmet-Hathor, was sometimes depicted as a | + | The gentle form that Sekhmet had become by the end of the tale was identical in character to Hathor, and so a new cult arose, at the start of the Middle Kingdom, which dualistically identified Sekhmet with Hathor, making them one goddess, ''Sekhmet-Hathor'', with two sides. Consequently, Hathor, as [[Sekhmet-Hathor]], was sometimes depicted as a [[lion]]ess. Sometimes this joint name [[sound change|was corrupted]] to '''Sekhathor''' (also spelt '''Sechat-Hor''', '''Sekhat-Heru'''), meaning ''(one who) remembers Horus'' (the uncorrupted form would mean ''(the) powerful house of Horus'' but Ra had displaced Horus, thus the change). The two goddesses were so different, indeed almost diametrically opposed, however, that the new identification did not last. |

==Wife of Thoth== | ==Wife of Thoth== | ||

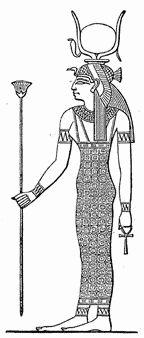

| − | When Horus | + | [[Image:Hathor-Meyers.png|thumb|right|Drawing of Hathor bearing all of her symbols and showing details of her traditional gown]] |

| + | When [[Horus]] became identified as Ra in the changing [[Egyptian pantheon]], under the name ''Ra-Herakhty'', Hathor's position became unclear, since in later myths she had been the wife of Ra, but in earlier myths she was the mother of Horus. Many attempts to solve this gave Ra-Herakhty a new wife, [[Ausaas]], to solve this issue around who was Ra-Herakhty's wife and Hathor became identified only as the mother of the new sun god. However, this left open the unsolved question of how Hathor could be his mother, since this would imply that Ra-Herakhty was a child of Hathor, rather than a creator. Such inconsistencies developed as the Egyptian pantheon changed over the thousands of years becoming very complex, and some were never resolved. | ||

| − | In areas where the cult of [[Thoth]] | + | In areas where the cult of [[Thoth]] became strong, Thoth was identified as the creator, leading to it being said that Thoth was the father of Ra-Herakhty, thus in this version Hathor, as the mother of Ra-Herakhty, was referred to as Thoth's wife. In this version of what is called the [[Ogdoad]] [[cosmogeny]], Ra-Herakhty was depicted as a young child, often referred to as ''Neferhor''. When considered the wife of Thoth, Hathor often was depicted as a woman nursing her child. |

| − | Since | + | Since [[Seshat]]had earlier been considered to be Thoth's wife, Hathor began to be attributed with many of Seshat's features. Since Seshat was associated with records and with acting as witness at the judgment of souls in [[Duat]], these aspects became attributed to Hathor, which, together with her position as goddess of all that was good, lead to her being described as the ''(one who) expels evil'', which in [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] is '''Nechmetawaj''' also spelt '''Nehmet-awai''', and '''Nehmetawy'''). ''Nechmetawaj'' can also be understood to mean ''(one who) recovers stolen goods'', and so, in this form, she became goddess of stolen goods. |

| − | Outside the Thoth cult, it was considered important to retain the position of Ra-Herakhty (i.e. Ra) as self-created (via only the primal forces of the Ogdoad). Consequently, Hathor could not be identified as Ra-Herakhty's mother. Hathor's role in the process of death, that of welcoming the newly dead with food and drink, lead, in such circumstances, to her being identified as a jolly wife for [[Nehebkau]], the guardian of the entrance to the underworld | + | Outside the Thoth cult during these times, it was considered important to retain the position of Ra-Herakhty (i.e. Ra) as self-created (via only the primal forces of the Ogdoad). Consequently, Hathor could not be identified as Ra-Herakhty's mother. Hathor's role in the process of death, that of welcoming the newly dead with food and drink, lead, in such circumstances, to her being identified as a jolly wife for [[Nehebkau]], the guardian of the entrance to the underworld and binder of the [[Egyptian soul|Ka]]. Nethertheless, in this form, she retained the name of ''Nechmetawaj'', since her aspect as a returner of stolen goods was so important to society that it was retained as one of her roles. |

== Hathor outside the Nile river in Egypt == | == Hathor outside the Nile river in Egypt == | ||

| − | |||

| − | Hathor was worshipped in [[Canaan]] in the [[11th century B.C.E.]], which at that time was ruled by Egypt, at her holy city of [[Hazor]], which the [[Old Testament]] claims was destroyed by [[Joshua]] ([[Book of Joshua|Joshua]] 11:13, 21). The Sinai Tablets show that the Hebrew workers in the mines of [[Sinai Peninsula|Sinai]] about 1500 B.C.E. worshipped Hathor, whom they identified with | + | Hathor was worshipped in [[Canaan]] in the [[11th century B.C.E.|eleventh century B.C.E.]], which at that time was ruled by Egypt, at her holy city of [[Hazor]], or [[Tel Hazor]] which the [[Old Testament]] claims was destroyed by [[Joshua]] ([[Book of Joshua|Joshua]] 11:13, 21). |

| + | |||

| + | The Sinai Tablets show that the Hebrew workers in the mines of [[Sinai Peninsula|Sinai]] about [[1500 B.C.E.]] worshipped Hathor, whom they identified with their goddess [[Astarte]]. Some theories state that the [[golden calf]] mentioned in the Bible was meant to refer to a statue of the goddess Hathor ([[Exodus]] 32:4-32:6.). A major temple to Hathor was constructed by [[Seti II]] at the copper mines at [[Timna]] in [[Edom]]ite [[Seir]]. Serabit el-Khadim (Arabic: سرابت الخادم) (Arabic, also transliterated Serabit al-Khadim, Serabit el-Khadem) is a locality in the south-west Sinai Peninsula where [[turquoise]] was mined extensively in antiquity, mainly by the ancient Egyptians. Archaeological excavation, initially by Sir Flinders Petrie, revealed the ancient mining camps and a long-lived Temple of Hathor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Greeks]], who became rulers of Egypt for three hundred years before the Roman domination in 31 B.C.E., also loved Hathor and equated her with their own goddess of love and beauty, [[Aphrodite]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references /> | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | * Assmann, Jan. ''In search for God in ancient Egypt''. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293. | ||

| + | * Breasted, James Henry. ''Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454. | ||

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Egyptian Book of the Dead''. 1895. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ebod/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Egyptian Heaven and Hell''. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis. ''The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology''. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969. | ||

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts''. 1912. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/leg/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Rosetta Stone''. 1893, 1905. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/trs/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Dennis, James Teackle (translator). ''The Burden of Isis''. 1910. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/boi/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. ''Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.''. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X. | ||

| + | * Erman, Adolf. ''A handbook of Egyptian religion''. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907. | ||

| + | * Frankfort, Henri. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion''. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772. | ||

| + | * Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). ''The Leyden Papyrus''. 1904. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/dmp/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Klotz, David. ''Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple''. New Haven, 2006. ISBN 0974002526. | ||

| + | * Larson, Martin A. ''The Story of Christian Origins''. 1977. ISBN 0883310902. | ||

| + | * Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. ''Daily life of the Egyptian gods''. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158. | ||

| + | * Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). ''The Pyramid Texts''. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Najovits, Simson. ''Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, Vol. 1: The Contexts''. Algora Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0875862225. | ||

| + | * Pinch, Geraldine. ''Handbook of Egyptian mythology''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428. | ||

| + | * Shafer, Byron E. (editor). ''Temples of ancient Egypt''. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991. | ||

| + | * Wilkinson, Richard H. ''The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt''. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.thekeep.org/~kunoichi/kunoichi/themestream/hathor.html Hathor Article by Caroline Seawright] | *[http://www.thekeep.org/~kunoichi/kunoichi/themestream/hathor.html Hathor Article by Caroline Seawright] | ||

| − | *[http://www.hethert.org | + | *[http://www.hethert.org Het-Hert site, another name for Hathor] |

| + | |||

| − | + | [[Category:Egyptian goddesses]] | |

| + | [[Category:Fertility goddesses]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Stellar goddesses]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Arts goddesses]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Animal goddesses]] | ||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

[[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

| − | {{credit| | + | {{Ancient Egypt}} |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{credit|158396340}} | ||

Revision as of 04:55, 24 September 2007

In Egyptian mythology, Hathor (Egyptian for house of Horus) was originally a personification of the Milky Way, which was seen as the milk that flowed from the udders of a heavenly cow. Hathor was an ancient goddess, and was worshipped as a cow-deity from at least 2700 B.C.E.,[1] during the second dynasty. Her worship the Egyptians goes back earlier however, possibly, even by the Scorpion King who ruled during the Protodynastic Period before the dynasties began. His name, Serqet, may refer to the goddess Serket.

The name Hathor refers to the encirclement by her, in the form of the Milky Way, of the night sky and consequently of the god of the sky, Horus who was said to be her son. Later she was described as the wife of Ra, the creator whose own cosmic birth was formalised in the Ogdoad cosmogeny after his worship arose and displaced that of Horus. At that time images of Ra bear the eye motif.

An alternate name for Hathor, which persisted for 3,000 years, was Mehturt (also spelt Mehurt, Mehet-Weret, and Mehet-uret), meaning great flood, a direct reference to her being the milky way.[citation needed]

The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and the king, leading the ancient Egyptians to describe it as The Nile in the Sky. Due to this, and the name mehturt, she was identified as responsible for the yearly inundation of the Nile.

Another consequence of this name is that she was seen as a herald of imminent birth, as when the amniotic sac breaks and floods its waters, it is a medical indicator that the child is due to be born extremely soon.

Another interpretation of the Milky Way was that it was the primal snake, Wadjet, the protector of Egypt who was closely associated with Hathor and other early deities among the various aspects of the great mother goddess, including Mut and Naunet.

Hathor also was favoured as a protector in desert regions (see Serabit el-Khadim).

Hathor in an Egyptian Context

As an Egyptian deity, Hathor belonged to a religious, mythological and cosmological belief system that developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to around 525 B.C.E.[1] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[2] The cults were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[3] Yet, the Egyptian gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “If we compare two of [the Egyptian gods] … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[4] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanent—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[5] Thus, those Egyptian gods who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Furthermore, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[6]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely defined by the geographical and calendrical realities of its believers' lives. The Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[7] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[8] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

Milky Way personified

Few contemporary human cultures live without illumination at night that blocks the nighttime sky, some could not describe the Milky Way and the stars that dominated the nights of these people and their imaginations. It is a hazy band of white light that is seen in the night sky, arching across the entire celestial sphere. Anthropologists presume that legends built around the aspects of the sky and other natural phenomenon became the traditions upon which the myths were described while viewing the sky. Associations with the deities exists in all cultures.

In Egypt the primordial waters were associated with the Nile River which often flooded the land, both feared and bountiful. The Milky Way often was described as the river in the sky in Egyptian texts.

Associations, images, and symbols

Eventually, Hathor's identity as a cow, meant that she became identified with another ancient cow-goddess of fertility, Bat. It still remains an unanswered question amongst Egyptologists as to why Bat survived as an independent goddess for so long. Bat was, in some respects, connected to the Ba, an aspect of the soul, and so Hathor gained an association with the afterlife. It was said that, with her motherly character, she greeted the souls of the dead in Duat, and proffered them with refreshments of food and drink. She also was described sometimes as mistress of the acropolis.

The assimilation of Bat, who was associated with the sistrum, a musical instrument, brought with it an association with music. In this form, Hathor's cult became centred in Dendera and was led by priests who also were dancers, singers, and other entertainers.

Hathor also became associated with the menat, the turquoise musical necklace often worn by women. A hymn to Hathor says:

- Thou art the Mistress of Jubilation, the Queen of the Dance, the Mistress of Music, the Queen of the Harp Playing, the Lady of the Choral Dance, the Queen of Wreath Weaving, the Mistress of Inebriety Without End.

Essentially, Hathor had become a goddess of Joy, and so she was deeply loved by the general population, and truly revered by women, who aspired to embody her multifaceted role as wife, mother, and lover. In this capacity, she gained the titles of Lady of the House of Jubilation, and The One Who Fills the Sanctuary with Joy.

The worship of Hathor was so popular that more festivals were dedicated to her honour than any other Egyptian deity, and more children were named after this goddess than any other. Even Hathor's priesthood was unusual, in that both men and women became her priests.

Bloodthirsty warrior

The Middle Kingdom was founded when Upper Egypt's pharaoh, Mentuhotep II, took control over Lower Egypt, which had become independent during the First Intermediate Period by force. This unification had been achieved by a brutal war that was to last some twenty-eight years with many casualties, but when it ceased, calm returned, and the reign of the next pharaoh, Mentuhotep III, was peaceful, and Egypt once again became prosperous. A tale, from the perspective of Lower Egypt, developed around this experience of protracted war.

In the tale following the war, Ra (representing the pharaoh of Upper Egypt) was no longer respected by the people (of Lower Egypt) and they ceased to obey his authority, which made him so angry that he sent out Sekhmet (war goddess of Upper Egypt) to destroy them. Sekhmet became bloodthirsty and the slaughter was great because she could not be stopped. As the slaughter continued, fear that all of humanity would be destroyed arose among the deities and Ra was charged with stopping her. Ra poured huge quantities of blood-coloured beer on the ground to trick Sekhmet. She drank so much of it—thinking it to be blood—that she became too drunk to continue the slaughter and humanity was saved. Afterward Sekhmet became loving and kind.

The gentle form that Sekhmet had become by the end of the tale was identical in character to Hathor, and so a new cult arose, at the start of the Middle Kingdom, which dualistically identified Sekhmet with Hathor, making them one goddess, Sekhmet-Hathor, with two sides. Consequently, Hathor, as Sekhmet-Hathor, was sometimes depicted as a lioness. Sometimes this joint name was corrupted to Sekhathor (also spelt Sechat-Hor, Sekhat-Heru), meaning (one who) remembers Horus (the uncorrupted form would mean (the) powerful house of Horus but Ra had displaced Horus, thus the change). The two goddesses were so different, indeed almost diametrically opposed, however, that the new identification did not last.

Wife of Thoth

When Horus became identified as Ra in the changing Egyptian pantheon, under the name Ra-Herakhty, Hathor's position became unclear, since in later myths she had been the wife of Ra, but in earlier myths she was the mother of Horus. Many attempts to solve this gave Ra-Herakhty a new wife, Ausaas, to solve this issue around who was Ra-Herakhty's wife and Hathor became identified only as the mother of the new sun god. However, this left open the unsolved question of how Hathor could be his mother, since this would imply that Ra-Herakhty was a child of Hathor, rather than a creator. Such inconsistencies developed as the Egyptian pantheon changed over the thousands of years becoming very complex, and some were never resolved.

In areas where the cult of Thoth became strong, Thoth was identified as the creator, leading to it being said that Thoth was the father of Ra-Herakhty, thus in this version Hathor, as the mother of Ra-Herakhty, was referred to as Thoth's wife. In this version of what is called the Ogdoad cosmogeny, Ra-Herakhty was depicted as a young child, often referred to as Neferhor. When considered the wife of Thoth, Hathor often was depicted as a woman nursing her child.

Since Seshathad earlier been considered to be Thoth's wife, Hathor began to be attributed with many of Seshat's features. Since Seshat was associated with records and with acting as witness at the judgment of souls in Duat, these aspects became attributed to Hathor, which, together with her position as goddess of all that was good, lead to her being described as the (one who) expels evil, which in Egyptian is Nechmetawaj also spelt Nehmet-awai, and Nehmetawy). Nechmetawaj can also be understood to mean (one who) recovers stolen goods, and so, in this form, she became goddess of stolen goods.

Outside the Thoth cult during these times, it was considered important to retain the position of Ra-Herakhty (i.e. Ra) as self-created (via only the primal forces of the Ogdoad). Consequently, Hathor could not be identified as Ra-Herakhty's mother. Hathor's role in the process of death, that of welcoming the newly dead with food and drink, lead, in such circumstances, to her being identified as a jolly wife for Nehebkau, the guardian of the entrance to the underworld and binder of the Ka. Nethertheless, in this form, she retained the name of Nechmetawaj, since her aspect as a returner of stolen goods was so important to society that it was retained as one of her roles.

Hathor outside the Nile river in Egypt

Hathor was worshipped in Canaan in the eleventh century B.C.E., which at that time was ruled by Egypt, at her holy city of Hazor, or Tel Hazor which the Old Testament claims was destroyed by Joshua (Joshua 11:13, 21).

The Sinai Tablets show that the Hebrew workers in the mines of Sinai about 1500 B.C.E. worshipped Hathor, whom they identified with their goddess Astarte. Some theories state that the golden calf mentioned in the Bible was meant to refer to a statue of the goddess Hathor (Exodus 32:4-32:6.). A major temple to Hathor was constructed by Seti II at the copper mines at Timna in Edomite Seir. Serabit el-Khadim (Arabic: سرابت الخادم) (Arabic, also transliterated Serabit al-Khadim, Serabit el-Khadem) is a locality in the south-west Sinai Peninsula where turquoise was mined extensively in antiquity, mainly by the ancient Egyptians. Archaeological excavation, initially by Sir Flinders Petrie, revealed the ancient mining camps and a long-lived Temple of Hathor.

The Greeks, who became rulers of Egypt for three hundred years before the Roman domination in 31 B.C.E., also loved Hathor and equated her with their own goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite.

Notes

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dennis, James Teackle (translator). The Burden of Isis. 1910. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Klotz, David. Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple. New Haven, 2006. ISBN 0974002526.

- Larson, Martin A. The Story of Christian Origins. 1977. ISBN 0883310902.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Najovits, Simson. Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, Vol. 1: The Contexts. Algora Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0875862225.

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

External links

| Topics about Ancient Egypt edit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Places: Nile river | Niwt/Waset/Thebes | Alexandria | Annu/Iunu/Heliopolis | Luxor | Abdju/Abydos | Giza | Ineb Hedj/Memphis | Djanet/Tanis | Rosetta | Akhetaten/Amarna | Atef-Pehu/Fayyum | Abu/Yebu/Elephantine | Saqqara | Dahshur | |||

| Gods associated with the Ogdoad: Amun | Amunet | Huh/Hauhet | Kuk/Kauket | Nu/Naunet | Ra | Hor/Horus | Hathor | Anupu/Anubis | Mut | |||

| Gods of the Ennead: Atum | Shu | Tefnut | Geb | Nuit | Ausare/Osiris | Aset/Isis | Set | Nebet Het/Nephthys | |||

| War gods: Bast | Anhur | Maahes | Sekhmet | Pakhet | |||

| Deified concepts: Chons | Maàt | Hu | Saa | Shai | Renenutet| Min | Hapy | |||

| Other gods: Djehuty/Thoth | Ptah | Sobek | Chnum | Taweret | Bes | Seker | |||

| Death: Mummy | Four sons of Horus | Canopic jars | Ankh | Book of the Dead | KV | Mortuary temple | Ushabti | |||

| Buildings: Pyramids | Karnak Temple | Sphinx | Great Lighthouse | Great Library | Deir el-Bahri | Colossi of Memnon | Ramesseum | Abu Simbel | |||

| Writing: Egyptian hieroglyphs | Egyptian numerals | Transliteration of ancient Egyptian | Demotic | Hieratic | |||

| Chronology: Ancient Egypt | Greek and Roman Egypt | Early Arab Egypt | Ottoman Egypt | Muhammad Ali and his successors | Modern Egypt | |||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.