Difference between revisions of "Halakha" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Halakha today) |

|||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

==Gentiles and Jewish law== | ==Gentiles and Jewish law== | ||

| − | Judaism holds that [[Gentile]]s are obliged only to follow the seven [[Noahide Laws]], given to [[Noah]] after the flood. | + | Halakhic Judaism holds that [[Gentile]]s are obliged only to follow the seven [[Noahide Laws]], given to [[Noah]] after the flood. These laws are specified in the [[Talmud]] (Tractate Sanhedrin 57a), including six "negative" commandments and one "positive" one: |

#[[Murder]] is forbidden. | #[[Murder]] is forbidden. | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

#[[Blasphemy|Blaspheming]] God is forbidden. | #[[Blasphemy|Blaspheming]] God is forbidden. | ||

#Society must establish a fair system of legal [[justice]]. | #Society must establish a fair system of legal [[justice]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Early Christianity and halakha=== | ===Early Christianity and halakha=== | ||

| − | The history of earliest Christianity in some ways hinged on halakhic debates. Jesus himself may be seen as a promoter of | + | The history of earliest Christianity in some ways hinged on halakhic debates. Jesus himself may be seen as a promoter of liberal halakhic attitudes on some matters, conservative ones on others. For example, his reported lax attitude on such issues as hand-washing and commerce with Gentiles marked him as a halakhic liberal, while his strict attitude on the question of divorce showed a more conservative bent. The question of Jesus' attitude toward Halakha, however, is clouded by the fact that the Gospels were written after Christianity had already broken with Judaism for the most part, with only the [[Gospel of Matthew]] maintaining a basically Jewish character in which Jesus urges his disciples to "exceed the righteousness of the Pharisees." One thing all four Gospels agree upon, however, is that at least some of the [[Pharisee]]s considered Jesus too liberal in his attitude toward Halakha. |

| − | A generation later, the Christian movement itself would be divided over certain basic question of halakah. The Apostle Paul would argue, for example, that Gentile believers did not need to | + | A generation later, the Christian movement itself would be divided over certain basic question of halakah. The [[Apostle Paul]] would argue, for example, that Gentile believers did not need to follow the Jewish law, while others—known in later times as [[Judaizers]]—insisted that new believers convert to Judaism and accept the full burden of Halakha before being considered as members of the church. According to Acts 15:29, a compromise was worked out in which Gentiles did not have to be circumcised to join the church, but they must follow the Noahide commandments such as refraining from idolatry, fornication, and certain dietary restrictions. |

| − | This, solution, however did not solve the problem of Jewish Christians interacting with Gentile Christians in worship and table fellowship, resulting in a heated disagreement between Paul and Peter at Antioch (Galatians 2) in which Paul accused Peter of hypocrisy for separating himself from the Gentile Christians in order to please certain "men from James." Ultimately Christianity would reject even some of the Noahide comments specified in Acts 15 | + | This, solution, however, did not solve the problem of Jewish Christians interacting with Gentile Christians in worship and table fellowship, resulting in a heated disagreement between Paul and Peter at Antioch (Galatians 2) in which Paul accused Peter of hypocrisy for separating himself from the Gentile Christians in order to please certain "men from James." Ultimately Christianity would reject even some of the Noahide comments specified in Acts 15, while retaining the [[Ten Commandments]] and other aspects of early Halakha. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 14:01, 1 July 2008

Halakha (Hebrew: הלכה, also spelled Halacha) is the collective corpus of Jewish religious law, including biblical law (the 613 biblical commandments) and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions. Halakha guides not only religious practices and beliefs, but numerous aspects of day-to-day life. Often translated as "Jewish Law," a more literal rendering of the term is "the path" or "the way of walking."

Orthodox Jews still adhere fairly strictly to traditional halakhic rules. Conservative Judaism also hold Halakha to be binding, but believes in a progressive philosophy by which Halakha can be adjusted to changing social norms. Reform and Reconstructionist Jews believe that Jews are no longer required by God to adhere to Halakha. Reflecting the cultural diversity of Jewish communities, slightly different approaches to Halakha are also found among Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, Sephardi, and Yemenite Jews.

Historically, Halakha served many Jewish communities as enforceable civil, criminal, and religious law, but in the modern era Jews are generally bound to Halakhah only by their voluntary consent. Religious sanctions such as excommuncation may be imposed by religious authorities, however, and in the state of Israel certain areas of family and personal status law are governed by rabbinic interpretations of Halakha.

In the Christian tradition, some of the arguments between Jesus and his Jewish opponents may be seen as an internal debate among fellow Jews over halakhic issues such as hand-washing, Sabbath observance, and association with Gentiles and sinners. In both the Christian and Muslim worlds, some aspects of civil and criminal law may be seen as deriving from early halakhic tradition, such as the Ten Commandments.

Terminology

The term Halakha may refer to a single law, to the literary corpus of rabbinic legal texts, or to the overall system of interpreting religious law. The Halakha is often contrasted with the Aggadah, the diverse corpus of rabbinic non-legal literature. At the same time, since writers of Halakha may draw upon the aggadic literature, there is a dynamic interchange between the two genres.

Controversies over halakhic issues lend rabbinic literature much of its creative and intellectual appeal. With few exceptions, these debates are not settled through authoritative structures. Instead, Jews interested in observing Halakha may choose to follow specific rabbis, affiliate with a community following a specific halakhic tradition, or interpret the Halakha based on their own conscientious study.

Torah and Halakha

Halakha constitutes the practical application of the 613 mitzvot ("commandments," singular: mitzvah) in the Torah, (the five books of Moses) as developed through discussion and debate in the classical rabbinic literature. Its laws, guidelines, and opinions cover a vast range of situations and principles. It is also the subject of intense study in yeshivas.

According to the Talmud (Tractate Makot), the commandments include 248 positive mitzvot and 365 negative mitzvot given in the Torah, plus seven mitzvot legislated by the rabbis of antiquity. However, the exact numbers of distinct commandments is also a subject of debate. Positive commandments require an action to be performed, and thus bring one closer to God. Negative commandments forbid a specific action, and violating them creates a distance from God. One of the positive commandments is to "be holy" as God is holy (Leviticus 19:2 and elsewhere). This is achieved as one attempts, so far as possible, to live in accordance with God's wishes for humanity, striving to live in accordance with each of the commandments with every moment of one's life.[1]

Classical rabbinic Judaism has two basic categories of laws:

- Laws believed revealed by God to the Jewish people at Mount Sinai (including both the written Pentateuch and its elucidation by the prophets and rabbinical sages);

- Laws believed to be of human origin, including specific rabbinical decrees, interpretations, customs, etc.

Laws of the first category are not optional, with exceptions made only for life-saving and similar emergency circumstances.[2] Halakhic authorities may disagree on which laws fall into which categories or the circumstances (if any) under which prior rabbinic rulings can be changed by contemporary rabbis, but all halakhic Jews hold that both categories exist.

The sources and process of Halakha

The boundaries of Jewish law are determined through the halakhic process, a religious-ethical system of legal reasoning and debate. Rabbis generally base their opinions on the primary sources of Halakha as well as on precedent set by previous rabbinic opinions. The major sources consulted include:

- The commandments specified in the Hebrew Bible, including both the Torah and other writings, especially the works of the prophets

- The foundational Talmudic literature, especially the Mishna and the Babylonian Talmud, with associated commentaries

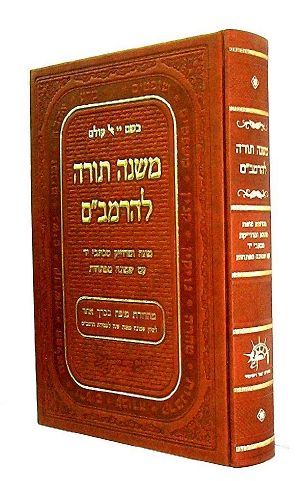

- Post-Talmudic compilations of Halakha such as Maimonides' twelfth-century Mishneh Torah and the sixteenth-century Shulchan Aruch collected by Rabbi Yosef Karo

- Regulations promulgated by various rabbis and communal bodies, such as the Gezeirah (rules intended to prevent violations of the commandments) and the Takkanah (legislation not directly justified by the commandments)

- Minhagim: customs, community practices, and traditions

- Responsa, known as the she'eloth u-teshuvoth (literally "questions and answers") including both Talmudic and post-Talmudic literature

- Laws of the land (Dina d'malchuta dina): non-Jewish laws recognized as binding on Jewish citizens, provided that they are not contrary to the laws of Judaism.

In antiquity, the ruling council known as the Sanhedrin functioned as both the supreme court and legislative body of Judaism. That court ceased to function in its full mode in 40 C.E.

Today, no single body is generally regarded as having the authority to determine universally recognized halakhic precedents. The authoritative application of Jewish law is generally left to the local chief rabbi or rabbinical courts, where these exist. When a rabbinic posek ("decisor") proposes a new interpretation of a law, that interpretation may be considered binding for the rabbi's questioner or immediate community. Depending on the stature of the posek and the quality of the decision, this ruling may be gradually accepted by other rabbis and members of similar Jewish communities elsewhere.

The halakhic tradition embodies a wide range of principles that permit judicial discretion and deviation. Generally speaking, a rabbi in any one period will not overrule specific laws from an earlier era, unless supported by a relevant earlier precedent. There are important exceptions to this principle, however, which empower the posek or beth din (court) to create innovative solutions.

Within certain Jewish communities, formal organized halakhic bodies do exist. Modern Orthodox rabbis, for example, generally agree with the views set by the leaders of the Rabbinical Council of America. Within Conservative Judaism, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards sets the denomination's halakhic policy. Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism do not consider Halakha binding on modern Jews.

Legislation

Technically, one may discern two powerful legal tools within the halakhic system:

- Gezeirah: "preventative legislation" of the Rabbis, intended to prevent violations of the commandments

- Takkanah: "positive legislation," practices instituted by the Rabbis not based (directly) on the commandments

In common parlance the general term takkanah (pl. takkanot) may refer to either of the above. Takkanot, in general, do not affect or restrict observance of Torah mitzvot. However, the Talmud states that in some cases, the sages had the authority to "uproot matters from the Torah." For example, after the Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed and no central place of worship existed for all Jews, blowing the shofar was restricted, in order to prevent players from carrying the instrument on the Sabbath. In rare cases, the sages allowed the temporary violation a Torah prohibition in order to maintain the Jewish system as a whole. This was part of the basis, for example, for Esther's marriage to the Gentile king Ahasuerus, which ordinarily would be considered a serious violation.

Sin

Judaism regards the violation of any of the commandments to be a sin. Unlike in most forms of Christianity, sins do not always involve a willful moral lapse, however. Three categories of sin are:

- Pesha—an intentional sin, committed in deliberate defiance of God

- Avon—a sin of lust or uncontrollable passion committed knowingly, and thus a moral evil, but not not necessarily in defiance of God

- Chet—an "unintentional sin" committed unknowingly or by accident, such as unknowingly eating non-kosher food

Judaism holds that no human being is perfect, and all people have sinned many times. However a state of sin does not condemn a person to damnation; there is always a road of teshuva (repentance, literally: "return").

Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics is the study of rules for the exact determination of the meaning of a text. It played a notable role in early rabbinic Jewish discussion. Compilations of such hermeneutic rules include:

- the seven Rules of Hillel

- the 13 Rules of Rabbi Ishmael

- the 32 Rules of Rabbi Eliezer ben Jose ha-Gelili.

Neither Hillel, Ishmael, nor Eliezer sought to give a complete enumeration of the rules of interpretation current in his day. They restricted themselves to a compilation of the principal methods of logical deduction, which they called middot (measures).

The antiquity of the rules can be determined only by the dates of the authorities who quote them. In general, they can not safely be declared older than the tanna (sage) to whom they are first ascribed. It is generally agreed, however, that the seven middot of Hillel and the 13 of Ishmael are earlier than the time of these tannaim, who were the first to transmit them.

The Talmud itself gives no information concerning the origin of the middot, although the Geonim (sages of the Middle Ages) regarded them as Sinaitic, a view firmly rejected by modern Jewish historians.

The middot seem to have been first laid down as abstract rules by the teachers of Hillel, although they were not immediately recognized by all as valid and binding. Different schools modified, restricted, or expanded them in various ways. Rabbis Akiba and Ishmael especially contributed to the development or establishment of these rules. Akiba devoted his attention to the grammatical and exegetical rules, while Ishmael developed the logical ones. The rules laid down by one school were frequently rejected by another because the principles that guided them in their respective formulations were essentially different. Such dialectics form an essential part of the Halakha, and thus Jewish tradition is noted for its attitude that Jews may conscientiously degree about many halakhic issues.

Halakhic eras

The following are the traditional historical divisions forming the halakhic eras from the time of the tannaim to the present day.

- The Tannaim (literally the "repeaters"): the sages of the Mishnah (70–200 C.E.)

- The Amoraim (literally the "sayers"): the sages of the Gemara (200–500)

- The Savoraim (literally the "reasoners"): the classical Persian rabbis (500–600)

- The Geonim (literally the "prides" or "geniuses"): the great rabbis of Babylonia (650–1250)

- The Rishonim (literally the "firsts"): the major rabbis of the early medieval period (1250–1550) preceding the Shulchan Aruch

- The Acharonim (literally the "lasts") are the great rabbis from about 1550 to the present.

Halakha today

Three basic divisions may be recognized among Jewish believers today regarding the question of Halakah:

Orthodox Judaism holds that Jewish law was dictated by God to Moses essentially as it exists today. However, there is significant disagreement within Orthodox Judaism, particularly between Haredi Judaism and Modern Orthodox Judaism, about the circumstances under which post-Sinaitic additions can be changed, the Haredi being the more conservative.

Conservative Judaism holds that Halakha is normative and binding on Jews, being developed as a partnership between God and His people based on Torah. However Conservative Judaism rejects Orthodox "fundamentalism" and welcomes modern critical study of the Hebrew Bible and Talmud. Conservatives emphasize that Halakha is an evolving process subject to interpretation by rabbis in every time period, including the present.

Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism both hold that the legal regulations of the Talmud and other halakhic literature are no longer binding on Jews. Some members of these movements see the Halakha as a personal starting-point, but leave the interpretation of the commandments and their applicability up to the individual conscience.

Gentiles and Jewish law

Halakhic Judaism holds that Gentiles are obliged only to follow the seven Noahide Laws, given to Noah after the flood. These laws are specified in the Talmud (Tractate Sanhedrin 57a), including six "negative" commandments and one "positive" one:

- Murder is forbidden.

- Theft is forbidden.

- Sexual immorality is forbidden.

- Eating flesh cut from a still-living animal is forbidden.

- Belief in and worship or prayer to "idols" is forbidden.

- Blaspheming God is forbidden.

- Society must establish a fair system of legal justice.

Early Christianity and halakha

The history of earliest Christianity in some ways hinged on halakhic debates. Jesus himself may be seen as a promoter of liberal halakhic attitudes on some matters, conservative ones on others. For example, his reported lax attitude on such issues as hand-washing and commerce with Gentiles marked him as a halakhic liberal, while his strict attitude on the question of divorce showed a more conservative bent. The question of Jesus' attitude toward Halakha, however, is clouded by the fact that the Gospels were written after Christianity had already broken with Judaism for the most part, with only the Gospel of Matthew maintaining a basically Jewish character in which Jesus urges his disciples to "exceed the righteousness of the Pharisees." One thing all four Gospels agree upon, however, is that at least some of the Pharisees considered Jesus too liberal in his attitude toward Halakha.

A generation later, the Christian movement itself would be divided over certain basic question of halakah. The Apostle Paul would argue, for example, that Gentile believers did not need to follow the Jewish law, while others—known in later times as Judaizers—insisted that new believers convert to Judaism and accept the full burden of Halakha before being considered as members of the church. According to Acts 15:29, a compromise was worked out in which Gentiles did not have to be circumcised to join the church, but they must follow the Noahide commandments such as refraining from idolatry, fornication, and certain dietary restrictions.

This, solution, however, did not solve the problem of Jewish Christians interacting with Gentile Christians in worship and table fellowship, resulting in a heated disagreement between Paul and Peter at Antioch (Galatians 2) in which Paul accused Peter of hypocrisy for separating himself from the Gentile Christians in order to please certain "men from James." Ultimately Christianity would reject even some of the Noahide comments specified in Acts 15, while retaining the Ten Commandments and other aspects of early Halakha.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bleich, J. David. Contemporary Halakhic Problems. New York: Ktav. ISBN 0870684507

- Katz, Jacob. Divine Law in Human Hands—Case Studies in Halakhic Flexibility. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. ISBN 9652239801

- Lewittes, Mendell. Jewish Law: An Introduction. Northvale, N.J: Jason Aronson. ISBN 1568213026

- Roth, Joel. Halakhic Process: A Systemic Analysis. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary. ISBN 0873340353

- Spero, Shubert. Morality, Halakha, and the Jewish Tradition. The Library of Jewish law and ethics, v. 9. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1983.

- Tomson, Peter J. Paul and the Jewish Law: Halakha in the Letters of the Apostle to the Gentiles. Compendia rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum, v. 1. Assen [Netherlands]: Van Gorcum, 1990. ISBN 9780800624675

External links

- Judaism 101 Laws and Customs - Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- The Rules of Halacha. www.chabad.org. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- Talmudic Law. www.jewishencyclopedia.com.Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- Law, Codification of. www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- Entry on Halakhah. hsf.bgu.ac.il. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- Religious Praxis: The Meaning of Halakhah. tpeople.co.il. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- Orthodox Responses to Sociological and Technological Change. www.daat.ac.il. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ The Christian version of this commandment is found in Jesus' saying "Be perfect as your Heavenly Father is perfect." (Mt. 5:44)

- ↑ Some sects, such as the Qumran community which produced the Damascus Document, did not permit exceptions to the rule against working on the Sabbath even to throw a rope or lower a ladder to a person who might otherwise drown.