Difference between revisions of "Church and State" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Contemporary) |

(replaced link) |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

==The principle of separation== | ==The principle of separation== | ||

| + | {{Main|Separation of Church and State in the United States}} | ||

"Separation of Church and State" is often discussed as political and legal principle derived from the [[First Amendment]] of the [[United States Constitution]], which reads, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..." | "Separation of Church and State" is often discussed as political and legal principle derived from the [[First Amendment]] of the [[United States Constitution]], which reads, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..." | ||

Revision as of 15:17, 10 August 2007

The relationship between church and state is a crucial one in the history of religious and political freedom. The term is not necessarily limited to the relations between Christian churches and governments, but can also refer to religions generally. The history of "church-state" relations may thus be said to date back to ancient times long before the advent of Christianity. However these relations are a particularly important theme in the history of Christian civilization, especially in Europe and the Americas.

Many modern democracies separate church and state in order that government and religious institutions should function independently of one another. The term "separation of church and state" often refers to the combination of two principles: a secular government and freedom of religious exercise. However, while separation of church and state generally correlates with high degrees of religious freedom, it should be noted that some governments that maintain state churches have a good record of religious freedom, while some strongly secular governments do not.

The term separation of church and state is often traced to a letter written by Thomas Jefferson in 1802 to the Danbury Baptists, in which he referred to the First Amendment of the United States Constitution as creating a "wall of separation" between church and state. The phrase was later quoted by the United States Supreme Court, first in 1878, and then in a series of cases beginning in 1947.

Internationally, the separation of church and state is closely related to other important social and political ideas, including secularism, disestablishment, religious liberty, religious pluralism and laicite. While most western democracies generally adhere to the separation of church and state, the specific practice of this principle varies widely in specific applications.

History

Ancient

In many ancient cultures, the political ruler was also the highest religious leader and sometimes considered divine. One of the earliest recorded episodes challenging a state religion of this type the story of Moses and Aaron confronting the king of Egypt in order, ostensibly, to win the right to hold a three-day festival honoring the Hebrew god Yahweh. According to the Book of Exodus, the Hebrews' petition was granted only after a series of miraculous plagues were visited upon the Egyptians. Moses then led the Israelites out of Egypt, never to return.

The first government declaration officially granting toleration to non-state religions was issued in the ancient Persian Empire by its founder, Cyrus the Great in the fifth century B.C.E. Cyrus reversed the policy of his Babylonian predecessors and allowed captured religious icons to be returned to their places of origin. He also funded the restoration of important native shrines, including the Temple of Jerusalem.

Ancient Jewish tradition, on the other hand, affirmed a strict state monotheism and attempted to suppress non-Israelite religions by destroying unauthorized altars and sometimes slaughtering the priests of rival faiths. Although many of the kings of Judah and Israel in fact tolerated other religious traditions, they were condemned for this policy by the prophets and other biblical writers.

In the Orient, the right to worship freely was promoted by most ancient Indian dynasties until around 1200 C.E., King Ashoka, (304-232 B.C.E.), an early practitioner of this principle, wrote that he "honors all sects" and stated: "One must not exalt one’s creed discrediting all others, nor must one degrade these others without legitimate reasons. One must, on the contrary, render to other creeds the honor befitting them."

In the West, Alexander the Great and subsequent Greek and Roman rulers generally followed a policy of religious toleration toward local religions. However, they also insisted that indigenous peoples pay homage to the state religion as well, a policy which put monotheistic faiths such as Judaism and Christianity in a position of either compromising their own principles or rebelling against the state's authority. Some emperors tolerated Jewish and Christian non-compliance with the requirement to honor the gods of the state, while others persecuted them as rebels and traitors. The Christian attitude toward the state, meanwhile, was generally based on the attitude that one should “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and to God the things that are God's” (Mark 12:17).

Later Roman Empire

Under Constantine the Great, however, Christianity was officially favored over other faiths, and the formerly Christian Church became the official state religion under Theodosius I in the early fifth century CE. It is from this point that issues of church and state began to take on major political significance.

The later Roman Empire under Christianity repressed non-Christian religions and Christian heresies alike. Jews, too, suffered under the influence of Christian bishops such as Ambrose of Milan, who prevailed in his opinion that a Christian emperor must not compel a local bishop to pay for the rebuilding of a synagogue he had led his parishioners to destroy. This precedent was also an important one for asserting the independence of the Western church from the state.

Under the influence of Saint Augustine of Hippo, the Western church adopted a somewhat pessimistic attitude toward the state as a "secular" power whose role was to uphold Christian law and order and to punish those who do evil.[1]The Eastern church took a more optimistic view, seeing a positive role for the state as God's agent in society. A third course would be adopted in lands affected by the rise of Islam.

In the eastern Byzantine Empire, the emperors, although sometimes deferring to powerful bishops and monks on matters of theology, considered themselves to be the "supreme pontiff" of the Church, as well as head of state. Justinian the Great promulgated the doctrine of harmonia, which asserted that the Christian state and the Church should work together for God's will on earth under the emperor's leadership. A strong supporter of Orthodoxy and opponent of heresy, Justinian secured from the bishops in attendance at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 an affirmation that nothing could be done in the Church contrary to the emperor's will. This doctrine remained in effect until the Ottomans conquered Constantinople (now Istanbul) in the fifteenth century.[2]

In the West, the Bishop of Rome emerged as the central figure of the Roman Catholic Church and often asserted his spiritual authority over various kings, on both theological and political matters. Pope Gelasius I promulgated the "Two Swords" doctrine in 494 C.E. insisting the the emperor must defer to the pope on spiritual matters and also declaring that the pope's power is generally "more weighty" that the emperor's. He wrote:

There are two powers, august Emperor, by which this world is chiefly ruled, namely, the sacred authority of the priests and the royal power. Of these that of the priests is the more weighty, since they have to render an account for even the kings of men in the divine judgment. You are also aware, dear son, that while you are permitted honorably to rule over humankind, yet in things divine you bow your head humbly before the leaders of the clergy and await from their hands the means of your salvation.

In the meantime, the advent of Islam created still another attitude toward the relationship between religion and the state. Islamic lands generally recognized no distinction between religious and secular government until the period of the Ottoman Empire beginning with Osman I in the early fourteenth century. Islamic lands were ruled by the Islamic codes, or shari'a, usually under a caliph as the supreme political leader. Although forcible conversions of non-Muslims were allowed in some circumstances, Islamic law guaranteed the rights of both Christians and Jews to worship according to their own traditions. Thus, Christians were usually granted greater religious freedom in Muslim lands than Muslims were granted in Christian countries; and Jews generally fared better under Muslim rulers than Christian ones.

Nationalism and the Renaissance

In Europe, the supremacy of the pope faced challenges from kings and western emperors on a number of matters, leading to power struggles and crises of leadership, notably in the Investiture Controversy of the eleventh century over the question of who had the authority to appoint local bishops. A see-saw battle ensured during the succeeding centuries as kings sought to assert their independence from Rome while the papacy engaged in various programs of reform on the one hand and the exercise of considerable power against rebellious kings on the other, through such methods as excommunication and interdicts.

During the Renaissance, nationalist theorists began to affirm that kings had absolute authority within their realms to rule on spiritual matters as well as secular ones. Kings began increasingly to challenge papal authority on matters ranging from their own divorces to questions of international relations and the right to try clergy in secular courts. This climate was a crucial factor in the success of the Protestant Reformation, not only in England, where Henry VIII successfully established himself as head of the Church of England after the pope refused to grant him a divorce, but also in Europe, where the Lutheran Church received crucial support from various princes determined to assert their independence from Rome for political as well as spiritual reasons.

Modern period

Despite the Reformation's success, the principle of separation of church and state was still far from being established. Indeed, the Protestant churches were just as willing as the Catholic Church to use the authority of the state to repress their religious opponents, and Protestant princes often used state churches for their own political ends. Years of religious wars eventually led to various affirmations of religious toleration in Europe, notably the Peace of Westphalia, signed in 1648. In England, after years of bloodshed and persecution on all sides, John Locke penned his Essays of Civil Government and Letter Concerning Toleration. These seminal documents in the history of church and state played a significant role in both the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and later in the American Revolution. Locke wrote: "The care of souls cannot belong to the civil magistrate, because his power consists only in outward force; but true and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God."

Locke’s ideas were to be further enshrined in the American Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson in 1776. Another of Jefferson's works, the 1779 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, proclaimed:

[N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief...

The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) likewise guaranteed that: "No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law."

The U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights, passed in 1791, specifically banned the American government from creating a state religion, declaring: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

In practice, the French Revolution took a somewhat different attitude from its American counterpart regarding the question of religious liberty. In the French case, not only would the state reject the establishment of any particular religion, it would take a vigilant stance against religions involving themselves in the political arena. The American tradition, on the other hand, welcomed religious arguments in public debate and allowed clergymen of various faiths to serve in public office as long as they adhered to the Constitution. The French leadership, having suffered from centuries of religious wars, was also deeply suspicious of religious passion and tended to repress its public expression, while the Americans adopted a positive attitude toward newer and smaller faiths which fostered a lively religious pluralism. These two approaches would set the tone for future debates about the nature and proper degree of separation between church and state in the coming centuries.

Religion and state in Isalm

Contemporary

Many variations on separation of church and state can be seen today. Some countries with high degrees of religious freedom and tolerance have still maintained state churches or financial ties with certain religious organizations into the twentieth century. In England, for example, there is a constitutionally established state religion but the British tradition is very inclusive of other faiths as well. [3] In Norway, similarly, the King is also the leader of the state church, and the 12th article of the Constitution of Norway requires more than half of the members of the Norwegian Council of State to be members of the state church. Yet, the country is generally recognized to have a high degree of religious freedom. In countries like these, the head of government or head of state or other high-ranking official figures may be legally required to be a member of a given faith. Powers to appoint high-ranking members of the state churches are also often still vested in the worldly governments.

Several European countries such as Germany, Austria, and several Eastern European nations officially support certain religions such as the Catholic Church, Lutheran (Evangelical) Church, or the Russian Orthodox Church, while officially recognizing other churches as legitimate, and refusing to register newer, smaller, or more controversial religions. Some go so far as to prohibit unregistered groups from owning property or distributing religious literature.

Other countries maintain a more militant brand of separation church and state. Two prominent examples are France and Turkey.[4] The French version of separation is called laïcité. This model of a secularist state protects the religious institutions from some types of state interference, but public expression by religious institutions and the clergy on political matters is limited. Religious minorities are also less free to express themselves publicly by wearing distinctive clothing in the workplace or in public schools.

A more liberal secularist philosophy is expressed in the American model, which allows a broad array of religious expression on public issues and goes out of its way to facilitate religious minorities in the workplace, public schools, and even prisons.[5]

The opposite end of the spectrum from separation of church and state is a theocracy, in which the state is founded upon the institution of religion, and the rule of law is based on the dictates of a religious court. Examples include Saudi Arabia, the Vatican, and Iran. In such countries, state affairs are managed by religious authority, or at least by its consent. In theocracies, the degree to which those who are not members of the official religion are to be protected is usually decided by experts of the official religion.

A special case may be seen in the Marxist-Leninist countries, in which the state takes a militantly atheistic standpoint and attempts to varying degrees to suppress or even destroy religion, which Marx saw as the "opiate of the people" and a tool of capitalist oppression. Some have argued that in Marxist states, the ideology of Marxism-Leninism constitutes a kind of atheist religion, and that such states in fact do not separate "church and state" but replace a theistic state religion with an atheistic one. While Marxist-Leninist states today are rare, North Korea still officially holds to this ideology and China still adopts a hostile attitude toward various religious groups based in part on the Marxist attitude of its leaders.

The principle of separation

"Separation of Church and State" is often discussed as political and legal principle derived from the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which reads, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

However, there are inevitable entanglements between the institutions of religion and the state, inasmuch as religious organizations and their adherents are a part of civil society.[6] Moreover, private religious practices can sometimes come into conflict with broad legislation not intending to target any particular religious minority. Examples include laws against polygamy, animal sacrifice, hallucinogenic drugs; and laws requiring the swearing of oaths, military service, public school attendance, etc. Each of these complicate the idea of absolute separation.

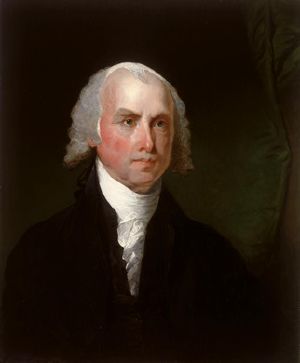

The phrase "separation of church and state" is derived from a letter written by Thomas Jefferson to a group of Danbury Baptists. In that letter, referencing the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, Jefferson writes: "I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church & State." Another early user of the term was James Madison, the principal drafter of the United States Bill of Rights, who wrote of the "total separation of the church from the state." [7]

The United States Supreme Court has referenced the separation of church and state more than 25 times, first in 1878. The term was used and defended heavily by the Court until the early 1970s. Since that time, the Court has distanced itself from the term somewhat, often suggesting the metaphor of a "wall of separation" conveys hostility to religion in contrast to Jefferson's original meaning "...in behalf of the rights of [religious] conscience."

Specific issues

Separation of church and state can thus occur in various ways and to various degrees. In practice the principle has not been a simple one. Nor should separation of church and state be considered as synonymous with "separation of religion and politics." Both on the large issues and the details, a wide variety of policies can be found on church-state questions, both in the western democracies and nations committed to other political models such as Islamic government and Marxism.

A list of the issues in the separation between church and state in various parts of the world could include the following:

- Whether the state should officially establish a religion. State religions exist in relative free contries such as the England, as well as relatively unfree countries such as Saudi Arabia, as well as countries with a mixed record on religious and political freedom, such as Israel.

- Whether the state should act in a way that tends to favor certain religions over others, or which favors a religious attitude over a non-religious one. For example, is it better to encourage prayers in public schools, or to protect the rights of those students who might feel unconfortable with certain types of prayers.

- Whether the state should officially fund religious activities or schools associated with religious bodies. For example, should taxes go to pay the salaries of mainstream ministers, as they do in Germany and some other European countries today, or to aid non-religious education in Catholic schools.

- Whether the state should indirectly fund religious activities such as voluntary prayer meetings and Bible studies at public schools or religious displays on public properties.

- Whether the state should fund non-religious activities sponsored by religious organizations. For example, should the government support "faith-based" charitable programs to feed the hungry.

- Whether the state should not prescribe, proscribe, or amend religious beliefs. For example, can the state require students to say the words "under God" when pledging allegiance to their country; and can it prohibit preachers from giving sermons that denigrate homosexual acts as sinful?

- Whether the state should endorse, criticize, or ban any religious belief or practice. For example should the state prohibit the wearing of distinctive religious clothing, the practice of animal sacrifice, or the refusal by parents to accept medical treatment for their children? Should it ban the preaching of violent jihad against non-Islamic regimes?

- Whether the state should interfere in religious hierarchies or intervene in issues related to membership. This becomes a question for example when members of a religious congregation sue a religious institution for control of assets or for damages resulting from the behavior of religious officials, such as sexual abuse by priests.

- Whether a state may prohibit or restrict religious practices. Examples include polygamy, circmcision, female genital mutilation, animal sacrifices, holding prayer meetings in private homes, fundraising in public facilities, and evangelizing door to door.

- Whether the state may express religious beliefs. Is it appropriate for the state to print "In God We Trust" on its currency, to refer to God in its national anthem, or to cause its leaders to swear public oaths to God before assuming office?

- Whether political leaders may express religious preferences and doctrines in the course of their duties.

- Whether religious organizations may attempt to prescribe, proscribe, or amend civil or common law through political processes open to other institutions. Some nations forbid religions from supporting legislation, others limit it to a percentage of the religion's financial activity, and others place no restrictions on such activities.

- Whether religions may intervene in civil political processes between the state and other nations. Specifically does a church have the right to be a party in official international forums, as other non-gvoernmental organizations do.

- Whether religious institutions may actively endorse a political figure, or instead limit themselves to moral, ethical, and religious teaching. Some countries ban churches from political activity altogether; others impose penalties such as the loss of tax exemption for such actions; and state religions often actively endorse or oppose political candidates.

Conclusion

Issues of church and state often boil down to a question of minority rights versus the good of the whole as defined by the majority. State-recognized religions, even in relatively free political democracies such as Germany, easily use their privileged status to protect their own posistions while making it difficult for smaller and younger faiths to compete in the marketplace of ideas. On the other hand, overly-secular states may unwittingly trample on the sensitivities of religious people by, in effect, banning God from public life and discourse. The balance between the power of the state and the power of religious institutions remains a delicate one, intimately related to the question of religious and political freedom.

Because minority rights of all types can easily be trampled by the "tyranny of the majority," as strong and independent judiciary under a constitution which guarantees religious freedom for all is the best insurance that neither church nor state will come to dominate the rights of a nation's people.

Notes

- ↑ Augustine's teaching is the origin of the term "secular," by which he refered to the period prior to Christ's second advent.

- ↑ Ottoman ruler, Sultan Mehmed II, continued to practice the right of the Roman Emperor to appoint the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church. The subservient Orthodox attitude toward the state later influenced some Russian Orthodox leaders to adopt a cooperative attitude toward even the militantly atheistic Soviet government.

- ↑ Status of religious freedom by country, United Kingdom. en.wikipedia.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Turkey's policy has changed somewhat in recent years with the advent of a less-secularist government.

- ↑ American churches are forbidden, however, to support candidates for public office without jeopardizing their tax exemptions; and they are limited in the amount of money they can spend to affect pending legislation.

- ↑ Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306, 312 (1952). ("Otherwise the State and religion would be aliens to each other — hostile, suspicious, and even unfriendly. Churches could not be required to pay even property taxes. Municipalities would not be permitted to render police or fire protection to religious groups. Policemen who helped parishioners into their places of worship would violate the Constitution.")

- ↑ 1819 letter to Robert Walsh

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beneke, Chris. Beyond Toleration: The Religious Origins of American Pluralism. Oxford University Press, USA, 2006. ISBN 0-19-530555-8

- Cochran, Clark, and Davies, Derek. Church, State and Public Justice: Five Views. IVP Academic, 2007. ISBN 978-0830827961

- Church, Forrest. The Separation of Church and State: Writings on a Fundamental Freedom by America's Founders. Beacon Press; 1 edition, 2004. ISBN 978-0807077221

- Feldman, Noah. Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem—and What We Should Do About It. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Reprint edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0374530389

- Grasso, Kenneth. Catholicism and Religious Freedom: Contemporary Reflections on Vatican II's Declaration on Religious Liberty. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006. ISBN 978-0742551930

- Hamilton, Marci. God vs. the Gavel : Religion and the Rule of Law, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-85304-4

- Wampler, Dee. The Myth of Separation Between Church & State. Winepress Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-1579216238

External links

- American Center for Law and Justice. www.aclj.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- American Civil Liberties Union. www.aclu.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- American Jewish Committee. www.ajc.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Americans United for Separation of Church and State. www.au.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Anti-Defamation League(Jewish). www.adl.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs. www.bjcpa.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Freedom from Religion Foundation. www.ffrf.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Institute for the Secularisation of Islamic Society (ISIS). www.secularislam.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- North American Religious Liberty Association

- People for the American Way. www.religiousliberty.info. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Seventh-day Adventist Church State Council. www.churchstate.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty. www.becketfund.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- The Institute on Religion and Public Life. www.firstthings.com. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- The Rutherford Institute. www.rutherford.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- International Coalition Against Political Islam. www.icapi.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- No to Political Islam. www.ntpi.org. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.