Difference between revisions of "Bat" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

{{Taxobox | {{Taxobox | ||

| color = pink | | color = pink | ||

| name = Bats | | name = Bats | ||

| fossil_range = Late [[Paleocene]] - Recent | | fossil_range = Late [[Paleocene]] - Recent | ||

| − | | image = | + | | image = Big-eared-townsend-fledermaus.jpg |

| image_width = 240px | | image_width = 240px | ||

| − | | image_caption = | + | | image_caption = Townsend's Big-eared Bat, ''Corynorhinus townsendii'' |

| regnum = [[Animalia]] | | regnum = [[Animalia]] | ||

| phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] | | phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

| subdivision_ranks = Suborders | | subdivision_ranks = Suborders | ||

| subdivision = | | subdivision = | ||

| − | + | Megachiroptera<br/> | |

| − | + | Microchiroptera<br/> | |

See text for families. | See text for families. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | A '''bat''' is a [[mammal]] in the [[order (biology)|order]] '''Chiroptera'''. | + | A '''bat''' is a [[mammal]] in the [[order (biology)|order]] '''Chiroptera'''. Their most distinguishing feature is that their forelimbs are developed as [[wing]]s, making them the only mammals in the world naturally capable of [[flight]]. (Other mammals, such as [[Squirrel|flying squirrel]]s, [[lemur]]s, and flying opossums, can [[gliding|glide]] for limited distances). There are estimated to be about 1,100 [[species]] of bats worldwide, accounting for about 20 percent of all mammal species (Trudge 2000). |

| − | + | Though sometimes called "flying [[rodent]]s," "flying [[mice]]," or even mistaken for [[insect]]s and [[bird]]s, bats are not, in fact, rodents. | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [[ | + | While in [[China]] bats are considered a sign of good fortune, in the West they often are viewed negatively, such as associated with witches or vampires. Some bat-human interactions indeed are unfavorable for humans, such as those [[fruit]]-eating bats that compete for crops and the blood consuming vampire bats that can spread [[rabies]] to humans and domestic animals. But bats as a group provide important benefits to the [[ecosystem]] and to humans. Some of the smaller bat species are important [[pollination|pollinator]]s of some tropical [[flower]]s. Indeed, many tropical plants are now found to be totally dependent on them, not just for pollination, but for spreading their [[seed]]s by eating the resulting fruits. Insect-eating bats also play an important role in controlling insect populations, including night-flying [[mosquito]]s that might be carriers of [[malaria]] and other serious diseases. Some of the larger bats are a food source, and bat droppings, or guano, are harvested for use as fertilizer. |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [[ | + | Given the ability of fruit-eating bats to spread seeds, there are environmental concerns when a bat is [[introduced species|introduced]] in a new setting. [[Tenerife]] provides a recent example with the introduction of the [[Egyptian fruit bat]]. |

| − | Bats are divided into two distinct groups (or | + | |

| + | The word ''Chiroptera'' can be translated from the [[Greek language|Greek]] words for "hand wing," as the structure of the open wing is very similar to an outspread human hand with a [[skin|membrane]] (patagium) between the fingers that also stretches between hand and body. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Megabats versus microbats== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bats are divided into two distinct groups (or suborders): | ||

* '''Megachiroptera''' (megabats) | * '''Megachiroptera''' (megabats) | ||

* '''Microchiroptera''' (microbats/echolocating bats) | * '''Microchiroptera''' (microbats/echolocating bats) | ||

| − | Despite the name, not all megabats are larger than all microbats. | + | Despite the name, not all megabats are larger than microbats. The major distinction between the two suborders is based on other factors: |

| + | * Microbats use [[Animal echolocation|echolocation]], whereas megabats do not (except for ''[[Rousettus]]'' and relatives, which do). | ||

| + | * Microbats lack the [[claw]] at the second [[toe]] of the [[forelimb]]. | ||

| + | * The [[ear]]s of microbats do not form a closed ring, but the edges are separated from each other at the base of the ear. | ||

| + | * Microbats lack [[underfur]]; they have only [[guard hair]]s or are naked. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Megabats are found in [[Africa]] and [[Asia]]. They eat [[fruit]], [[nectar]] or [[pollen]], with some supplementing their diets with a few insects. Some megabat species are known as '''flying foxes.''' There are about 170 species of megabats. Microbats are found on all continents except [[Antarctica]]. Most of them eat [[insect]]s, while a few eat fruit, nectar, or small animals, or drink the [[blood]] of large animals. There are about 800 species of microbats (Richardson 2002). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Size== | ||

| + | [[Image:Golden crowned fruit bat.jpg|thumb|left|Giant golden-crowned flying fox, ''Acerodon jubatus,'' the largest bat]] | ||

| + | Most bats are very small for mammals. The smallest bat (also the smallest mammal) is the bumblebee bat, or Kitti's hog-nosed bat, of [[Thailand]] ''(Craseonycteris thonglongyai),'' which weighs only two grams (0.07 oz). The largest bat is the giant golden-crowned flying fox of the Philippines ''(Acerodon jubatus),'' which weighs 1500 grams (3.3 lbs) and has a wingspan of about 1.7 meters (5.5 feet). The largest bat in [[Canada]] is the hoary bat ''(Lasiurus cinereus),'' which weighs about 30 grams (0.9 oz). It could be sent through the mail with one first class Canadian postage stamp (Fenton 1998, Voelker 1986). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Flight== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bats fly with a swimming-like motion in which they grab pockets of air with their hand membranes. The fastest bat is the Mexican free-tailed bat ''(Tadarida brasiliensis),'' which can reach speeds of 40 mph in level flight and 80 mph in dives (65 and 130 kph). It has also been known to fly as high as 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) to take advantage of high-altitude winds. Many bats can hover, like [[hummingbird]]s, in order to pick insects off surfaces or to feed from flowers (Voelker 1986). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because their [[wing]]s are much thinner than those of birds, bats can maneuver more quickly and more precisely than [[bird]]s. The surface of their wings are also equipped with touch-sensitive receptors on small bumps called [[Merkel cell]]s, found in most mammals, including humans. But these sensitive areas are different in bats as each bump has a tiny hair in the center, making it even more sensitive, and allowing the bat to detect and collect information about the air flowing over its wings. An additional kind of receptor cell is found in the wing membrane of species that use their wings to catch prey. This receptor cell is sensitive to the stretching of the membrane. The cells are concentrated in areas of the membrane where insects hit the wings when the bats capture them (Calhoun 2005). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bat flight requires a great deal of energy. To power its flight muscles a typical bat's heart rate increases from 300 to 1000 beats per minute when it flies. In order to keep active bats need a good supply of high-energy food at least every few days. In places where this is not possible, many bats are [[Dormancy|dormant]] in winter to save energy (Richardson 2002). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Diet== | ||

| + | Most microbats depend on a diet of [[insect]]s. These are most often caught in the air while flying, although some bats capture insects on the ground or from plants. Some of the larger microbats eat larger animals such as [[fish]], [[frog]]s, [[mice]], small [[bird]]s, or even other bats. In the New World where megabats are absent, some microbats have taken to diets of fruit or nectar. The vampire bat of South America ''(Desmodus rotundus)'' drinks the blood of living animals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most megabats have diet of [[fruit]], while some drink the nectar of flowers. Megabats play an important role in both pollinating plants and in dispersing their seeds. Only the juice of the fruit is eaten while the seeds pass quickly through the digestive system, or are not eaten in the first place but only dropped to the ground. The very survival of some jungle trees depends on the megabats. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Insect-eating bats also play an important role in controlling insect populations (Richardson 2002). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Echolocation== | ||

| + | While true flight is unique to bats among mammals, echolocation is not. For example, some [[cetacean]]s, [[bird]]s, and [[shrew]]s are known to echolocate. Furthermore, not all bats echolocate, although it is quite common among the microbats (and ''Rousettus'' and relatives among the megabats.) | ||

| − | + | By emitting high-pitched sounds and listening to the [[echo (phenomenon)|echoes]], also known as sonar, microbats locate prey and other nearby objects. This is the process of echolocation. While some macrobats also use echolocation, the sounds are produced by tongue clicks and are used to find their way in caves and other dark places not to find food. | |

| − | *'''ORDER CHIROPTERA''' (Ky-rop`ter-a) (Gr. ''cheir'' | + | Echolocating microbats produce short bursts of sound, up to 200 per second. The sounds typically are too high pitched for humans to hear but are extremely loud, up to 110 decibels. (Many species utilize sounds within the range of human [[hearing (sense)|hearing]].) By using echolocation, microbats can detect flying insects and avoid obstacles to their flight, even in total darkness. The external ears of most microbats are very large for their size and are often shaped and folded in complex ways to enhance their reception of echolocation signals. Some bats also have a "noseleaf," a structure on the nose that is involved in echolocation (Fenton 1998, Voelker 1986). |

| + | |||

| + | Two groups of [[moth]]s exploit the bats' senses. Tiger moths produce ultrasonic signals to warn the bats that the moths are chemically-protected (aposematism) (this was once thought to be a form of "radar jamming," but this theory has been disproved). The moths Noctuidae have a hearing organ called a tympanum that responds to an incoming bat signal by causing the moth's flight muscles to twitch erratically, sending the moth into random evasive maneuvers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Roosting== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Almost all bats are active at night and rest during the day. Most bats hang head down from their hind feet while resting. It is vital for them to have roosting places where they are hidden from predators and that have proper temperature and humidity. Bats can quickly become dehydrated because of water loss through their wing membranes. (This might also be one reason that they fly at night.) Many bats roost in caves where they can find constant conditions and where predators can not reach them. One of the largest groups of bats was found in a cave in Arizona and contained 25 to 50 million Mexican free-tailed bats. Many megabats roost hanging from [[tree]] branches. Other bats roost in hollow trees or clinging to the sides of trees. Some rest in rolled up leaves or inside the stems of [[bamboo]] (Voelker 1986; Schober 1984). | ||

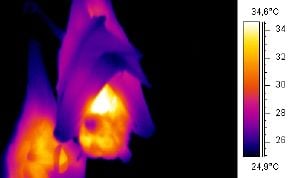

| + | [[Image:wiki bat.jpg|thumb|left|Thermographic image of a bat using trapped air as insulation.]] | ||

| + | Human activity has sometimes taken away bat roosting sites, for instance when old dead trees are cut down. Human visits to caves can also disturb bats. This can be especially harmful when it awakens them from hibernation and they have to spend precious energy finding new roosting places. On the other hand, bats have taken advantage of buildings for roosting sites. As people have become more interested in bat conservation measures have been taken to protect their roosting places. This can include excluding humans from roosting caves and providing bat boxes and even bat towers for alternative roosting sites (Schober 1984; Richardson 2002). A bat house constructed in 1991 at the University of Florida campus next to Lake Alice in Gainesville has a population of over 100,000 free-tailed bats (Nordlie 2001). | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Reproduction == | ||

| + | [[Image:Myotis myotis, nursery roost.jpg|thumb|Nursery roost of mouse-eared bats, ''Myotis myotis'']] | ||

| + | Mother bats usually have only one offspring per year. A baby bat is referred to as a [[pup]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pups are usually left in the roost when they are not [[breastfeeding|nursing]]. However, a newborn bat can cling to the [[fur]] of the mother and be transported, although they soon grow too large for this. It would be difficult for an adult bat to carry more than one young, but normally only one young is born. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bats often form nursery roosts, with many females giving birth in the same area, be it a [[cave]], a tree hole, or a cavity in a building. Mother bats are able to find their young in huge colonies of millions of other pups. Pups have even been seen to feed on other mothers' milk if their mother is dry. Only the mother cares for the young, and there is no continuous partnership with male bats. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ability to fly is congenital, but at birth the wings are too small to fly. Young microbats become independent at the age of six to eight weeks, megabats not until they are four months old. At the age of two years, most bats are sexually mature. A single bat can live over 20 years, but the bat population growth is limited by the slow [[birth rate]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Classification== | ||

| + | [[Image:Vespertilio murinus.jpg|thumb|Parti-colored bat, ''Vespertilio murinus'']] | ||

| + | [[Image:Pipistrellus pipistrellus01.jpg|thumb|Common pipistrelle, ''Pipistrellus pipistrellus'']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''ORDER CHIROPTERA''' (Ky-rop`ter-a) (Gr. ''cheir,'' hand, + ''pteron,'' wing) | ||

**'''Suborder Megachiroptera (megabats)''' | **'''Suborder Megachiroptera (megabats)''' | ||

*** Pteropodidae | *** Pteropodidae | ||

| Line 65: | Line 122: | ||

*** Superfamily Vespertilionoidea | *** Superfamily Vespertilionoidea | ||

**** Vespertilionidae (Vesper bats or Evening bats) | **** Vespertilionidae (Vesper bats or Evening bats) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Bats and humans== | |

| + | There is little direct interaction between bats and humans, although humans greatly benefit from the bats' role in controlling [[insect]] pests, especially night-flying [[mosquito]]s, which can be carriers of [[malaria]] and other serious diseases. No bat species has ever been domesticated, or even kept as a pet. Because of their small size, bats are not generally considered a food resource for humans, although in some places the larger megabats are caught and eaten. Bat droppings, or guano, are harvested from caves where bats roost for use as fertilizer (Schober 1984). | ||

| − | + | Major negative impacts of bats on human interests are confined to the vampire bat, which causes serious problems by spreading [[rabies]] to humans and domestic animals, and to some of the megabats, which prey on fruit crops. Other bats can also carry rabies but do not often spread the disease by biting humans. Rabies also can be contracted by contact with bat urine. Care must be taken in visiting bat roosting sites and in handling live bats (Fenton 1998). | |

| − | + | [[Image:Dsg UF Bat House 20050507.jpg|thumb|right|University of Florida bat house]] | |

| − | + | Some bat species are now endangered because of destruction of their habitats, while others have benefited by human activities such as clearing of forests, damming of streams, and construction, which can give them more hunting and roosting space. In Austin, Texas, the Congress Avenue bridge is the summer home to [[North America]]'s largest urban bat colony, an estimated 1,500,000 Mexican free-tailed bats, who eat an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 pounds of insects each night and attract 100,000 tourists each year. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Bats have figured in human culture and imagination. In the West, they have often been associated with evil, such as witches, vampires, or the devil. In China, however, they are considered a sign of good fortune and the word ''"fu"'' means both "bat" and "happiness" (Schober 1984). | ||

| + | With humankind's increasing concern over the natural world, bats have become more appreciated and efforts are being made for their preservation, including laws protecting them in many countries. In the [[United Kingdom]], all bats are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Acts, and even disturbing a bat or its roost can be punished with a heavy fine. In Sarawak, [[Malaysia]], bats are protected species under the Wildlife Protection Ordinance 1998. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Fenton, M. 1998. ''The Bat: Wings in the Night Sky'' | + | *Calhoun, M. 2005. [http://news.research.ohiou.edu/news/index.php?item=257 "Bats use touch receptors on wings to fly, catch prey, study finds"]. Ohio University. Retrieved September 3, 2007. |

| − | *Richardson, P. 2002. ''Bats'' | + | *Fenton, M. 1998. ''The Bat: Wings in the Night Sky.'' Buffalo, NY: Firefly Press. ISBN 1552092534 |

| − | *Schober, W. 1984. ''The Lives of Bats'' | + | *Nordlie, T. 2001. "Backyard bat houses promote pest control, says UF expert." ''UF News'' October 29, 2001. University of Florida. |

| − | *Voelker, W. 1986. ''The Natural History of Living Mammals'' | + | *Richardson, P. 2002. ''Bats.'' Washington, DC: Smithsonian Intitution Press. ISBN 1588340201 |

| − | + | *Schober, W. 1984. ''The Lives of Bats.'' New York: Arco Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0668059931 | |

| − | + | *Voelker, W. 1986. ''The Natural History of Living Mammals.'' Medford, NJ: Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0937548081 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Mammals}} | {{Mammals}} | ||

{{credit|Bat|151517605}} | {{credit|Bat|151517605}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Life sciences]][[Category:Animals]][[Category:Mammals]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:45, 28 July 2019

| Bats

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Townsend's Big-eared Bat, Corynorhinus townsendii

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Megachiroptera |

A bat is a mammal in the order Chiroptera. Their most distinguishing feature is that their forelimbs are developed as wings, making them the only mammals in the world naturally capable of flight. (Other mammals, such as flying squirrels, lemurs, and flying opossums, can glide for limited distances). There are estimated to be about 1,100 species of bats worldwide, accounting for about 20 percent of all mammal species (Trudge 2000).

Though sometimes called "flying rodents," "flying mice," or even mistaken for insects and birds, bats are not, in fact, rodents.

While in China bats are considered a sign of good fortune, in the West they often are viewed negatively, such as associated with witches or vampires. Some bat-human interactions indeed are unfavorable for humans, such as those fruit-eating bats that compete for crops and the blood consuming vampire bats that can spread rabies to humans and domestic animals. But bats as a group provide important benefits to the ecosystem and to humans. Some of the smaller bat species are important pollinators of some tropical flowers. Indeed, many tropical plants are now found to be totally dependent on them, not just for pollination, but for spreading their seeds by eating the resulting fruits. Insect-eating bats also play an important role in controlling insect populations, including night-flying mosquitos that might be carriers of malaria and other serious diseases. Some of the larger bats are a food source, and bat droppings, or guano, are harvested for use as fertilizer.

Given the ability of fruit-eating bats to spread seeds, there are environmental concerns when a bat is introduced in a new setting. Tenerife provides a recent example with the introduction of the Egyptian fruit bat.

The word Chiroptera can be translated from the Greek words for "hand wing," as the structure of the open wing is very similar to an outspread human hand with a membrane (patagium) between the fingers that also stretches between hand and body.

Megabats versus microbats

Bats are divided into two distinct groups (or suborders):

- Megachiroptera (megabats)

- Microchiroptera (microbats/echolocating bats)

Despite the name, not all megabats are larger than microbats. The major distinction between the two suborders is based on other factors:

- Microbats use echolocation, whereas megabats do not (except for Rousettus and relatives, which do).

- Microbats lack the claw at the second toe of the forelimb.

- The ears of microbats do not form a closed ring, but the edges are separated from each other at the base of the ear.

- Microbats lack underfur; they have only guard hairs or are naked.

Megabats are found in Africa and Asia. They eat fruit, nectar or pollen, with some supplementing their diets with a few insects. Some megabat species are known as flying foxes. There are about 170 species of megabats. Microbats are found on all continents except Antarctica. Most of them eat insects, while a few eat fruit, nectar, or small animals, or drink the blood of large animals. There are about 800 species of microbats (Richardson 2002).

Size

Most bats are very small for mammals. The smallest bat (also the smallest mammal) is the bumblebee bat, or Kitti's hog-nosed bat, of Thailand (Craseonycteris thonglongyai), which weighs only two grams (0.07 oz). The largest bat is the giant golden-crowned flying fox of the Philippines (Acerodon jubatus), which weighs 1500 grams (3.3 lbs) and has a wingspan of about 1.7 meters (5.5 feet). The largest bat in Canada is the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus), which weighs about 30 grams (0.9 oz). It could be sent through the mail with one first class Canadian postage stamp (Fenton 1998, Voelker 1986).

Flight

Bats fly with a swimming-like motion in which they grab pockets of air with their hand membranes. The fastest bat is the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), which can reach speeds of 40 mph in level flight and 80 mph in dives (65 and 130 kph). It has also been known to fly as high as 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) to take advantage of high-altitude winds. Many bats can hover, like hummingbirds, in order to pick insects off surfaces or to feed from flowers (Voelker 1986).

Because their wings are much thinner than those of birds, bats can maneuver more quickly and more precisely than birds. The surface of their wings are also equipped with touch-sensitive receptors on small bumps called Merkel cells, found in most mammals, including humans. But these sensitive areas are different in bats as each bump has a tiny hair in the center, making it even more sensitive, and allowing the bat to detect and collect information about the air flowing over its wings. An additional kind of receptor cell is found in the wing membrane of species that use their wings to catch prey. This receptor cell is sensitive to the stretching of the membrane. The cells are concentrated in areas of the membrane where insects hit the wings when the bats capture them (Calhoun 2005).

Bat flight requires a great deal of energy. To power its flight muscles a typical bat's heart rate increases from 300 to 1000 beats per minute when it flies. In order to keep active bats need a good supply of high-energy food at least every few days. In places where this is not possible, many bats are dormant in winter to save energy (Richardson 2002).

Diet

Most microbats depend on a diet of insects. These are most often caught in the air while flying, although some bats capture insects on the ground or from plants. Some of the larger microbats eat larger animals such as fish, frogs, mice, small birds, or even other bats. In the New World where megabats are absent, some microbats have taken to diets of fruit or nectar. The vampire bat of South America (Desmodus rotundus) drinks the blood of living animals.

Most megabats have diet of fruit, while some drink the nectar of flowers. Megabats play an important role in both pollinating plants and in dispersing their seeds. Only the juice of the fruit is eaten while the seeds pass quickly through the digestive system, or are not eaten in the first place but only dropped to the ground. The very survival of some jungle trees depends on the megabats.

Insect-eating bats also play an important role in controlling insect populations (Richardson 2002).

Echolocation

While true flight is unique to bats among mammals, echolocation is not. For example, some cetaceans, birds, and shrews are known to echolocate. Furthermore, not all bats echolocate, although it is quite common among the microbats (and Rousettus and relatives among the megabats.)

By emitting high-pitched sounds and listening to the echoes, also known as sonar, microbats locate prey and other nearby objects. This is the process of echolocation. While some macrobats also use echolocation, the sounds are produced by tongue clicks and are used to find their way in caves and other dark places not to find food.

Echolocating microbats produce short bursts of sound, up to 200 per second. The sounds typically are too high pitched for humans to hear but are extremely loud, up to 110 decibels. (Many species utilize sounds within the range of human hearing.) By using echolocation, microbats can detect flying insects and avoid obstacles to their flight, even in total darkness. The external ears of most microbats are very large for their size and are often shaped and folded in complex ways to enhance their reception of echolocation signals. Some bats also have a "noseleaf," a structure on the nose that is involved in echolocation (Fenton 1998, Voelker 1986).

Two groups of moths exploit the bats' senses. Tiger moths produce ultrasonic signals to warn the bats that the moths are chemically-protected (aposematism) (this was once thought to be a form of "radar jamming," but this theory has been disproved). The moths Noctuidae have a hearing organ called a tympanum that responds to an incoming bat signal by causing the moth's flight muscles to twitch erratically, sending the moth into random evasive maneuvers.

Roosting

Almost all bats are active at night and rest during the day. Most bats hang head down from their hind feet while resting. It is vital for them to have roosting places where they are hidden from predators and that have proper temperature and humidity. Bats can quickly become dehydrated because of water loss through their wing membranes. (This might also be one reason that they fly at night.) Many bats roost in caves where they can find constant conditions and where predators can not reach them. One of the largest groups of bats was found in a cave in Arizona and contained 25 to 50 million Mexican free-tailed bats. Many megabats roost hanging from tree branches. Other bats roost in hollow trees or clinging to the sides of trees. Some rest in rolled up leaves or inside the stems of bamboo (Voelker 1986; Schober 1984).

Human activity has sometimes taken away bat roosting sites, for instance when old dead trees are cut down. Human visits to caves can also disturb bats. This can be especially harmful when it awakens them from hibernation and they have to spend precious energy finding new roosting places. On the other hand, bats have taken advantage of buildings for roosting sites. As people have become more interested in bat conservation measures have been taken to protect their roosting places. This can include excluding humans from roosting caves and providing bat boxes and even bat towers for alternative roosting sites (Schober 1984; Richardson 2002). A bat house constructed in 1991 at the University of Florida campus next to Lake Alice in Gainesville has a population of over 100,000 free-tailed bats (Nordlie 2001).

Reproduction

Mother bats usually have only one offspring per year. A baby bat is referred to as a pup.

Pups are usually left in the roost when they are not nursing. However, a newborn bat can cling to the fur of the mother and be transported, although they soon grow too large for this. It would be difficult for an adult bat to carry more than one young, but normally only one young is born.

Bats often form nursery roosts, with many females giving birth in the same area, be it a cave, a tree hole, or a cavity in a building. Mother bats are able to find their young in huge colonies of millions of other pups. Pups have even been seen to feed on other mothers' milk if their mother is dry. Only the mother cares for the young, and there is no continuous partnership with male bats.

The ability to fly is congenital, but at birth the wings are too small to fly. Young microbats become independent at the age of six to eight weeks, megabats not until they are four months old. At the age of two years, most bats are sexually mature. A single bat can live over 20 years, but the bat population growth is limited by the slow birth rate.

Classification

- ORDER CHIROPTERA (Ky-rop`ter-a) (Gr. cheir, hand, + pteron, wing)

- Suborder Megachiroptera (megabats)

- Pteropodidae

- Suborder Microchiroptera (microbats)

- Superfamily Emballonuroidea

- Emballonuridae (Sac-winged or Sheath-tailed bats)

- Superfamily Molossoidea

- Antrozoidae (Pallid bats)

- Molossidae (Free-tailed bats)

- Superfamily Nataloidea

- Furipteridae (Smoky bats)

- Myzopodidae (Sucker-footed bats)

- Natalidae (Funnel-eared bats)

- Thyropteridae (Disk-winged bats)

- Superfamily Noctilionoidea

- Mormoopidae (Ghost-faced or Moustached bats)

- Mystacinidae (New Zealand short-tailed bats)

- Noctilionidae (Bulldog bats or Fisherman bats)

- Phyllostomidae (Leaf-nosed bats)

- Superfamily Rhinolophoidea

- Megadermatidae (False vampires)

- Nycteridae (Hollow-faced or Slit-faced bats)

- Rhinolophidae (Horseshoe bats)

- Superfamily Rhinopomatoidea

- Craseonycteridae (Bumblebee Bat or Kitti's Hog-nosed Bat)

- Rhinopomatidae (Mouse-tailed bats)

- Superfamily Vespertilionoidea

- Vespertilionidae (Vesper bats or Evening bats)

- Superfamily Emballonuroidea

- Suborder Megachiroptera (megabats)

Bats and humans

There is little direct interaction between bats and humans, although humans greatly benefit from the bats' role in controlling insect pests, especially night-flying mosquitos, which can be carriers of malaria and other serious diseases. No bat species has ever been domesticated, or even kept as a pet. Because of their small size, bats are not generally considered a food resource for humans, although in some places the larger megabats are caught and eaten. Bat droppings, or guano, are harvested from caves where bats roost for use as fertilizer (Schober 1984).

Major negative impacts of bats on human interests are confined to the vampire bat, which causes serious problems by spreading rabies to humans and domestic animals, and to some of the megabats, which prey on fruit crops. Other bats can also carry rabies but do not often spread the disease by biting humans. Rabies also can be contracted by contact with bat urine. Care must be taken in visiting bat roosting sites and in handling live bats (Fenton 1998).

Some bat species are now endangered because of destruction of their habitats, while others have benefited by human activities such as clearing of forests, damming of streams, and construction, which can give them more hunting and roosting space. In Austin, Texas, the Congress Avenue bridge is the summer home to North America's largest urban bat colony, an estimated 1,500,000 Mexican free-tailed bats, who eat an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 pounds of insects each night and attract 100,000 tourists each year.

Bats have figured in human culture and imagination. In the West, they have often been associated with evil, such as witches, vampires, or the devil. In China, however, they are considered a sign of good fortune and the word "fu" means both "bat" and "happiness" (Schober 1984).

With humankind's increasing concern over the natural world, bats have become more appreciated and efforts are being made for their preservation, including laws protecting them in many countries. In the United Kingdom, all bats are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Acts, and even disturbing a bat or its roost can be punished with a heavy fine. In Sarawak, Malaysia, bats are protected species under the Wildlife Protection Ordinance 1998.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Calhoun, M. 2005. "Bats use touch receptors on wings to fly, catch prey, study finds". Ohio University. Retrieved September 3, 2007.

- Fenton, M. 1998. The Bat: Wings in the Night Sky. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Press. ISBN 1552092534

- Nordlie, T. 2001. "Backyard bat houses promote pest control, says UF expert." UF News October 29, 2001. University of Florida.

- Richardson, P. 2002. Bats. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Intitution Press. ISBN 1588340201

- Schober, W. 1984. The Lives of Bats. New York: Arco Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0668059931

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, NJ: Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0937548081

| Mammals |

|---|

| Monotremata (platypus, echidnas) |

|

Marsupialia: | Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) | Didelphimorphia (opossums) | Microbiotheria | Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) | Dasyuromorphia (quolls and dunnarts) | Peramelemorphia (bilbies, bandicoots) | Diprotodontia (kangaroos and relatives) |

|

Placentalia: Cingulata (armadillos) | Pilosa (anteaters, sloths) | Afrosoricida (tenrecs, golden moles) | Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | Tubulidentata (aardvark) | Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | Proboscidea (elephants) | Sirenia (dugongs, manatees) | Soricomorpha (shrews, moles) | Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs and relatives) Chiroptera (bats) | Pholidota (pangolins)| Carnivora | Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) | Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) | Cetacea (whales, dolphins) | Rodentia (rodents) | Lagomorpha (rabbits and relatives) | Scandentia (treeshrews) | Dermoptera (colugos) | Primates | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.