Animal rights

- This article is about animal rights, the movement/philosophy. For the album, see Animal Rights (album).

Animal rights, animal liberation, or animal personhood, [1] is the movement to protect animals from being used or regarded as property by human beings. It is a radical social movement [2] [3] insofar as it aims not only to attain more humane treatment for animals, [4] but also to include species other than human beings within the moral community [5] by giving their basic interests — for example, the interest in avoiding suffering — the same consideration as those of human beings. [6] The claim is that animals should no longer be regarded legally or morally as property, or treated as resources for human purposes, but should instead be regarded as persons. [7] The movement seeks an end to all forms of what it sees as animal exploitation, including the use of animals in experiments, as sources of entertainment, as clothing, and as food. [4]

Animal rights or animal legal courses are now taught in 39 out of 180 United States law schools; and 47 of them have student animal legal defense groups. State, regional, and local bar associations are forming animal law committees to advocate for new animal rights and protections, [1] and the idea of extending personhood to animals has the support of some senior legal scholars, including Alan Dershowitz and Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School. [7] Two countries have passed legislation awarding recognition to the rights of animals. In 1992, Switzerland recognized animals as beings, not things, [8] and in 2002, a clause acknowledging the rights of animals was added to the German constitution. [8] The Seattle-based Great Ape Project, founded by philosophers Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer, is campaigning for the United Nations to adopt a Declaration on Great Apes, which would see gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees and bonobos included in a "community of equals" with human beings, extending to them the protection of three basic interests: the right to life, the protection of individual liberty, and the prohibition of torture. [9] This is seen by an increasing number of animal rights lawyers as a first step toward granting rights to other animals. [1] Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Critics of the concept of animal rights argue that, because animals do not have the capacity to enter into a social contract or make moral choices, [10] and cannot respect the rights of others or understand the concept of rights, they cannot be regarded as possessors of moral rights. The philosopher Roger Scruton argues that only human beings have duties and that "[t]he corollary is inescapable: we alone have rights." [11] Critics holding this position argue that there is nothing inherently wrong with using animals for food, as entertainment, and in research, though human beings may nevertheless have an obligation to ensure they do not suffer unnecessarily. [12] [13] This position is generally called the animal welfare position, and it is held by some of the oldest of the animal-protection agencies: for example, by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in the UK.

History of the concept

The 20th century animal rights movement grew out of the animal welfare movement, which can be traced back to the earliest philosophers. [6]

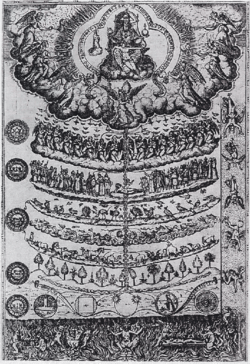

In the 6th century B.C.E., Pythagoras, the Greek philosopher and mathematician, urged respect for animals because he believed in the transmigration of souls between human and animals, although Aristotle, writing in the 4th century B.C.E., argued that animals ranked far below humans in the Great Chain of Being, or scala naturae, because of their alleged irrationality, and that as a result animals had no interests of their own, and existed only for human benefit. [6]

In the 17th century, the French philosopher René Descartes argued that animals had no souls, did not think, and could therefore be treated as if they were things, not beings. Against this, Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued, in the preface of his Discourse on Inequality (1754), that man starts as an animal, though not one "devoid of intellect and freedom." [14] However, as animals are sensitive beings, "they too ought to participate in natural right, and that man is subject to some sort of duties toward them," specifically "one [has] the right not to be uselessly mistreated by the other." [14]

Contemporaneous with Rousseau was the Scottish writer John Oswald, who died in 1793. In The Cry of Nature or an Appeal to Mercy and Justice on Behalf of the Persecuted Animals, Oswald argued that man is naturally equipped with feelings of mercy and compassion. [citation needed] If each man had to witness the death of the animals he ate, he argued, a vegetarian diet would be far more common. The division of labor, however, allows modern man to eat flesh without experiencing what Oswald called the prompting of man's natural sensitivities, while the brutalization of modern man made him inured to these sensitivities.

Later in the 18th century, one of the founders of modern utilitarianism, the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, argued that animal pain is as real and as morally relevant as human pain, and that "[t]he day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been witholden from them but by the hand of tyranny." [15] Bentham argued that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, must be the benchmark of how we treat other beings. If the ability to reason were the criterion, many human beings, including babies and disabled people, would also have to be treated as though they were things, famously writing that:

It may one day come to be recognized that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate.

What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month old. But suppose they were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being? The time will come when humanity will extend its mantle over everything which breathes ... [15]

Also in the 18th century, Arthur Schopenhauer argued that animals have the same essence as humans, despite lacking the faculty of reason. Although he considered vegetarianism to be only supererogatory, he argued for consideration to be given to animals in morality, and he opposed vivisection. His critique of Kantian ethics contains a lengthy and often furious polemic against the exclusion of animals in his moral system, which contained the famous line: "Cursed be any morality that does not see the essential unity in all eyes that see the sun." [citation needed]

The world's first animal welfare organization, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was founded in Britain in 1824, and similar groups soon sprang up elsewhere in Europe and then in North America. The first such group in the United States, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was chartered in the state of New York in 1866.

The concept of animal rights became the subject of an influential book in 1892, Animals' Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress, by English social reformer Henry Salt, who had formed the Humanitarian League a year earlier, with the objective of banning hunting as a sport.

By the late 20th century, animal welfare societies and laws against cruelty to animals existed in almost every country in the world. Specialized animal advocacy groups also proliferated, including those dedicated to the preservation of endangered species and others, like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), that protested against painful or brutal methods of hunting animals, the mistreatment of animals raised for human food in factory farms, and the use of animals in experiments and entertainment.

History of the modern movement

The modern animal rights movement can be traced to the early 1970s, and is one of the few examples of social movements that were created by philosophers, [3] and in which they remain in the forefront. In the early 1970s, a group of Oxford philosophers began to question whether the moral status of non-human animals was necessarily inferior to that of human beings. [3] This group included the psychologist Richard D. Ryder, who coined the phrase "speciesism" in 1970, first using it in a privately printed pamphlet [16] to describe the assignment of value to the interests of beings on the basis of their membership of a particular species.

Ryder became a contributor to the influential book Animals, Men and Morals: An Inquiry into the Maltreatment of Non-humans, edited by Roslind and Stanley Godlovitch and John Harris, and published in 1972. It was in a review of this book for the New York Review of Books that Peter Singer, now Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton, put forward the basic arguments, based on utilitarianism, that in 1975 became Animal Liberation, the book often referred to as the "bible" of the animal rights movement.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the movement was joined by a wide variety of academic and professional groups, including theologians, lawyers, physicians, psychologists, psychiatrists, veterinarians, [6] pathologists, and former vivisectionists.

Other books regarded as ground-breaking include Tom Regan's, The Case for Animal Rights (1983); James Rachels's, Created from Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism (1990); and Steven M. Wise's, Rattling the Cage: Toward Legal Rights for Animals (2000). [6]

Philosophy of the modern movement

Template:Alib Animal rights is the concept that all or some animals are entitled to possess their own lives; that they are deserving of, or already possess, certain moral rights; and that some basic rights for animals ought to be enshrined in law. The animal-rights view rejects the concept that animals are merely capital goods or property intended for the benefit of humans. The concept is often confused with animal welfare, which is the philosophy that takes cruelty towards animals and animal suffering into account, but that does not necessarily assign specific moral rights to them.

The animal-rights philosophy does not necessarily maintain that human and non-human animals are equal. For example, animal-rights advocates do not call for voting rights for chickens. Some activists also make a distinction between sentient or self-aware animals and other life forms, with the belief that only sentient animals, or perhaps only animals who have a significant degree of self-awareness, should be afforded the right to possess their own lives and bodies, without regard to how they are valued by humans. [citation needed] Others would extend this right to all animals, even those without developed nervous systems or self-consciousness. They maintain that any human being or institution that commodifies animals for food, entertainment, cosmetics, clothing, animal testing, or for any other reason, infringes upon their right to possess themselves and to pursue their own ends. [citation needed]

Few people would deny that non-human great apes are intelligent and aware of their own condition and goals, and may become frustrated when their freedoms are curtailed. In contrast, animals like jellyfish have simple nervous systems, and may be little more than automata, capable of basic reflexes but incapable of formulating any ends to their actions or plans to pursue them, and equally unable to notice whether they are in captivity. There is as yet no consensus with regard to which qualities make a living organism an animal in need of rights. The animal-rights debate, much like the abortion debate, is therefore marred by the difficulty that its proponents search for simple, clear-cut distinctions on which to base moral and political judgements, even though the biological realities of the problem present no hard and fast boundaries on which such distinctions could be based. From a neurobiological perspective, jellyfish, farmed chicken, laboratory mice, or pet cats would fall along different points on a complex spectrum from the "nearly vegetable" to the "highly sentient".

Currently, the two most prominent proponents of animal rights are the Australian philosopher Peter Singer and the American philosopher Thomas Regan.

In response to such challenges, opponents of animal rights have attempted to identify the “morally relevant” differences between humans and animals that supposedly justify the attribution of rights and interests to the former but not to the latter. Various such distinguishing features of humans have been proposed, including the possession of a soul, the ability to use language, self-consciousness, a high level of intelligence, and the ability to recognize the rights and interests of others. However, with the exception of the first feature (which cannot be established philosophically), such criteria face the difficulty that they do not seem to apply to all and only humans: each applies either to some but not to all humans or to all humans but also to some animals.

Different approaches

Peter Singer and Tom Regan are the best-known proponents of animal liberation, though they differ in their philosophical approaches. Another influential thinker is Gary L. Francione, who presents an abolitionist view that non-human animals should have the basic right not to be treated as the property of humans.

Utilitarian approach

Although Singer is the ideological founder of today's animal-rights movement, his approach to an animal's moral status is not based on the concept of rights, but on the utilitarian principle of equal consideration of interests. His 1975 book Animal Liberation argues that humans grant moral consideration to other humans not on the basis of intelligence (in the instance of children, or the mentally disabled), on the ability to moralize (criminals and the insane), or on any other attribute that is inherently human, but rather on their ability to experience suffering. [17] As animals also experience suffering, he argues, excluding animals from such consideration is a form of discrimination known as "speciesism."

Singer argues that the way in which humans use animals is not justified, because the benefits to humans are negligible compared to the amount of animal suffering they necessarily entail, and because the same benefits can be obtained in ways that do not involve the same degree of suffering.

Rights-based approach

Tom Regan (The Case for Animal Rights and Empty Cages) argues that non-human animals, as "subjects-of-a-life," are bearers of rights like humans. He argues that, because the moral rights of humans are based on their possession of certain cognitive abilities, and because these abilities are also possessed by at least some non-human animals, such animals must have the same moral rights as humans.

Animals in this class have "inherent value" as individuals, and cannot be regarded as means to an end. This is also called the "direct duty" view. According to Regan, we should abolish the breeding of animals for food, animal experimentation, and commercial hunting. Regan's theory does not extend to all sentient animals but only to those that can be regarded as "subjects-of-a-life." He argues that all normal mammals of at least one year of age would qualify in this regard.

While Singer is primarily concerned with improving the treatment of animals and accepts that, at least in some hypothetical scenarios, animals could be legitimately used for further (human or non-human) ends, Regan believes we ought to treat animals as we would persons, and he applies the strict Kantian idea that they ought never to be sacrificed as mere means to ends, and must be treated as ends unto themselves. Notably, Kant himself did not believe animals were subject to what he called the moral law; he believed we ought to show compassion, but primarily because not to do so brutalizes human beings, and not for the sake of animals themselves.

Despite these theoretical differences, both Singer and Regan agree about what to do in practise. For example, they agree that the adoption of a vegan diet and the abolition of nearly all forms of animal experimentation are ethically mandatory.

Abolitionist view

Gary Francione's work (Introduction to Animal Rights, et.al.) is based on the premise that if non-human animals are considered to be property then any rights that they may be granted would be directly undermined by that property status. He points out that a call to equally consider the 'interests' of your property against your own interests is absurd. Without the basic right not to be treated as the property of humans, non-human animals have no rights whatsoever, he says. Francione posits that sentience is the only valid determinant for moral standing, unlike Regan who sees qualitative degrees in the subjective experiences of his "subjects-of-a-life" based upon a loose determination of who falls within that category. Francione claims that there is no actual animal-rights movement in the United States, but only an animal-welfarist movement. In line with his philosophical position and his work in animal-rights law for the Animal Rights Law Project [3] at Rutgers University, he points out that any effort that does not advocate the abolition of the property status of animals is misguided, in that it inevitably results in the institutionalization of animal exploitation. It is logically inconsistent and doomed never to achieve its stated goal of improving the condition of animals, he argues. Francione holds that a society which regards dogs and cats as family members yet kills cows, chickens, and pigs for food exhibits what he calls "moral schizophrenia".

Animal rights in law

Animals are protected under the law, but in general their individual rights have no protection. There are criminal laws against cruelty to animals, laws that regulate the keeping of animals in cities and on farms, the transit of animals internationally, as well as quarantine and inspection provisions. These laws are designed to protect animals from unnecessary physical harm and to regulate the use of animals as food. In the common law, it is possible to create a charitable trust and have the trust empowered to see to the care of a particular animal after the death of the benefactor of the trust. Some individuals create such trusts in their will. Trusts of this kind can be upheld by the courts if properly drafted and if the testator is of sound mind. There are several movements in the UK campaigning to require the British parliament to award greater protection to animals. The legislation, if passed, will introduce a duty of care, whereby a keeper of an animal would commit an offence if he or she fails to take reasonable steps to ensure an animal’s welfare. This concept of giving the animal keeper a duty towards the animal is equivalent to granting the animal a right to proper welfare. The draft bill is supported by an RSPCA campaign.

Laws prohibiting cruelity against animals were not uncommon in ancient India. For example, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka issued laws to protect several animals, prohibited gratituous killing of all animals, condemned violent acts against animals, and provided facilities for their welfare. The first anti-cruelty law in the West was included in the legal code of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641. [6] In 1822, the British parliament adopted the Martin Act, which forbade the "cruel and improper Treatment" of large domestic animals. [6] The Tierschutzgesetz was passed in Germany in 1933 by the National Socialist government. Switzerland passed legislation in 1992 to recognize animals as beings, rather than things, and the protection of animals was enshrined in the German constitution in 2002, when its upper house of parliament voted to add the words "and animals" to the clause in the constitution obliging the state to protect the "natural foundations of life ... in the interests of future generations." [8] [4]

The State of Israel has banned dissections of animals in elementary and secondary schools; performances by trained animals in circuses; and has banned production of foie gras. [5] Over a dozen countries, as well as California and Chicago in the United States, have passed laws banning either foie gras production, sale, or both. [6]

Animal rights activism

- Further information: Animal liberation movement

In practice, those who advocate animal rights usually boycott a number of industries that use animals. Foremost among these is factory farming, [7] which produces the majority of meat, dairy products, and eggs in Western industrialized nations. The transportation of farm animals for slaughter, which often involves their live export, has in recent years been a major issue of campaigning for animal-rights groups, particularly in the UK.

The vast majority of animal-rights advocates adopt vegetarian or vegan diets; they may also avoid clothes made of animal skins, such as leather shoes, and will not use products such as cosmetics, pharmaceutical products, or certain inks or dyes known to contain animal byproducts. Goods containing ingredients that have been tested on animals are also avoided where possible. Company-wide boycotts are common. The Procter & Gamble corporation, for example, tests many of its products on animals, leading many animal-rights supporters to boycott all of their products, including food like peanut butter.

Many animal-rights advocates dedicate themselves to educating and persuading the public. Some organizations, like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, strive to do this by garnering media attention for animal-rights issues, often using outrageous stunts or advertisements to obtain media coverage for a more serious message.

There is a growing trend in the American animal-rights movement towards devoting all resources to vegetarian outreach. The 9.8 billion animals killed there for food use every year far exceeds the number of animals being exploited in other ways. Groups such as Vegan Outreach and Compassion Over Killing devote their time to exposing factory-farming practices by publishing information for consumers and by organizing undercover investigations.

A growing number of animal-rights activists engage in direct action. This typically involves the removal of animals from infiltrated facilities that use them or the damage of property at such facilities in order to cause financial loss. A number of incidents have involved violence or the threat of violence toward animal experimenters or associates involved in the use of animals. More extreme activists have attempted blackmail and other illegal activities to help aid their cause, such as the indimidation campaign to close Darley Oaks farm, which involved hate mail, malicious phonecalls, hoax bombs, arson attacks and property destruction, climaxing with the theft of Gladys Hammond's body (the owners' mother-in-law) from a Staffordshire grave. Most animal welfare groups condemned the attacks.

There are also a growing number of "open rescues," in which animal-rights advocates enter businesses to steal animals without trying to hide their identities. Open rescues tend to be carried out by committed individuals who are willing to go to jail if prosecuted, but so far no factory-farm owner has been willing to press charges, perhaps because of the negative publicity that would ensue. However some countries like Britain have proposed stricter laws to curb animal extremists. [8]

Criticism of animal rights

Rights require obligations

Critics such as Carl Cohen, professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan and the University of Michigan Medical School, oppose the granting of personhood to animals. Cohen wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine in October 1986: that "[t]he holders of rights must have the capacity to comprehend rules of duty governing all, including themselves. In applying such rules, the holders of rights must recognize possible conflicts between what is in their own interest and what is just. Only in a community of beings capable of self-restricting moral judgments can the concept of a right be correctly invoked."

Cohen rejects Peter Singer's argument that since a brain-damaged human could not exhibit the ability to make moral judgments, that moral judgments cannot be used as the distinguishing characteristic for determining who is awarded rights. Cohen states that the test for moral judgment "is not a test to be administered to humans one by one."

The British philosopher Roger Scruton has argued that rights can only be assigned to beings who are able to understand them and to reciprocate by observing their own obligations to other beings. Scruton also argues against animal rights on practical grounds. For example, in Animal Rights and Wrongs (2000), he supports foxhunting because it encourages humans to protect the habitat in which foxes live. However, he condemns factory farming because, he says, the animals are not provided with even a minimally acceptable life.

The Foundation for Animal Use and Education states that "[o]ur recognition of the rights of others stems from our unique human character as moral agents — that is, beings capable of making moral judgments and comprehending moral duty. Only human beings are capable of exercising moral judgment and recognizing the rights of one another. Animals do not exercise responsibility as moral agents. They do not recognize the rights of other animals. They kill and eat one another instinctively, as a matter of survival. They act from a combination of conditioning, fear, instinct and intelligence, but they do not exercise moral judgment in the process."

In The Animals Issue: Moral Theory in Practice (1992), the British philosopher Peter Carruthers argues that humans have obligations only to other beings who can take part in a hypothetical social contract.

Animal rights and human rights

Robert Bidinotto, a writer on environmental issues, said in a 1992 speech to the Northeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: "Strict observance of animal rights forbids even direct protection of people and their values against nature's many predators. Losses to people are acceptable ... losses to animals are not. Logically then, beavers may change the flow of streams, but Man must not. Locusts may denude hundreds of miles of plant life ... but Man must not. Cougars may eat sheep and chickens, but Man must not."

Chris DeRose, Director of Last Chance for Animals, stated: "If the death of one rat cured all disease, it wouldn't make any difference to me." When given the choice between rescuing a human baby or a dog after a lifeboat capsized, Susan Rich, PeTA Outreach Coordinator, answered, "I wouldn't know for sure ... I might choose the human baby or I might choose the dog." Tom Regan, animal rights philosopher, answered "If it were a retarded baby and a bright dog, I'd save the dog." Critics opposed to animal rights generally support animal welfare.

See also

- Altruism in animals

- Animal Liberation Front

- Animal liberation movement

- British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection

- Animal testing

- Animal welfare

- Ahimsa

- Barry Horne

- Blood sport

- Cinci Freedom

- Great ape personhood

- Imitation meat, In vitro meat

- Kashrut and animal welfare

- List of animal rights groups

- List of animal welfare and animal rights groups

- Open rescue

- Painism

- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals

- Painted fish

- Speciesism

- Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty

- United Animal Nations

- Veganism, Vegetarianism

- Vivisection

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Michael, Steven. "Animal personhood: A Threat to Research", The Physiologist, Volume 47, No. 6, December 2004.

- ↑ Guither, Harold D. Animal Rights: History and Scope of a Radical Social Movement. Southern Illinois University Press; reissue edition 1997. ISBN 0809321998

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Ethics," Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved June 17, 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Environmentalism," Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved June 17, 2006.

- ↑ Taylor, Angus. Animals and Ethics: An Overview of the Philosophical Debate, Broadview Press, May 2003. ISBN 1551115697

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 "Animal rights," Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved June 16, 2006.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "'Personhood' Redefined: Animal Rights Strategy Gets at the Essence of Being Human", Association of American Medical Colleges, retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Germany guarantees animal rights", CNN, June 21, 2002

- ↑ "Declaration on Great Apes", Great Ape Project, retrieved April 20, 2006.

- ↑ . Regan, Tom. "The Case for Animal Rights", retrieved April 20, 2006.

- ↑ Scruton, Roger. "Animal rights", City Journal, volume 10, issue 3, pages 100-107, summer 2000. ISSN 10608540.

- ↑ Frey, R.G. Interests and Rights: The Case against Animals. Clarendon Press, 1980 ISBN 0198244215

- ↑ Scruton, Roger. Animal Rights and Wrongs, Metro, 2000.ISBN 1900512815.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Discourse on Inequality, 1754, preface.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789. Latest edition: Adamant Media Corporation, 2005.

- ↑ Ryder, Richard D. "All beings that feel pain deserve human rights", The Guardian, August 6, 2005

- ↑ Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation, 1975; second edition, New York: Avon Books, 1990, ISBN 0940322005

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "Animal rights," Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved June 16, 2006.

- "Ethics," Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved June 17, 2006.

- "Environmentalism," Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved June 17, 2006.

- The Great Ape Project

- Meet Your Meat a PETA-produced slaughterhouse tour narrated by Alec Baldwin

- "'Personhood' Redefined: Animal Rights Strategy Gets at the Essence of Being Human", Association of American Medical Colleges, retrieved July 12, 2006.

- Bentham, Jeremy. Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1781; this edition edited by Burns, J.H. & Hart, H.L.A. Athlone Press 1970, ISBN 0485132117

- Frey, R.G. Interests and Rights: The Case Against Animals, 1980, Clarendon Press, ISBN 0198244215

- George. Kathryn Paxton. Animal, Vegetable, or Woman?, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0791446875

- Guither, Harold D. Animal Rights: History and Scope of a Radical Social Movement. Southern Illinois University Press; reissue edition 1997. ISBN 0809321998

- LaFollette, Hugh & Shanks, Niall. "The origin of speciesism" (pdf), Philosophy, January 1996, vol 71, issue 275.

- Michael, Steven. "Animal personhood: A Threat to Research", The Physiologist, Volume 47, No. 6, December 2004

- Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights, New York: Routledge, 1984, ISBN 0520049047

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Discourse on Inequality, 1754.

- Scruton, Roger. Animal Rights and Wrongs, 1997

- Scruton, Roger. "Animal rights", City Journal, Summer 2000

- Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation, 1975; second edition, New York: Avon Books, 1990, ISBN 0940322005

- Taylor, Angus. Animals and Ethics. Broadview Press, 2003

Further reading

Books about animal rights

- Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. New York: Continuum, 1996.

- ____________. The Pornography of Meat. New York: Continuum, 2004.

- ____________. & Donovan, Josephine. (eds). Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations. London: Duke University Press, 1995.

- ____________. The Social Construction of Edible Bodies

- Adams, Douglas. Meeting a Gorilla.

- Anstötz, Christopher. Profoundly Intellectually Disabled Humans

- Auxter, Thomas. The Right Not to Be Eaten

- Barnes, Donald J. A Matter of Change

- Barry, Brian. Why Not Noah's Ark?

- Bekoff, Marc. Common Sense, Cognitive Ethology and Evolution.

- Cantor, David. Items of Property.

- Cate, Dexter L. The Island of the Dragon

- Cavalieri, Paola. The Great Ape Project — and Beyond

- Carwardine, Mark. Meeting a Gorilla

- Clark, Stephen R.L. The Moral Status of Animals. (Clarendon Press 1977; pbk 1984).

- _______________. The Nature of the Beast. (Oxford University Press 1982; pbk 1984)

- _______________. Animals and their Moral Standing. (Routledge 1997)

- _______________. The Political Animal. (Routledge 1999)

- _______________. Biology and Christian Ethics. (Cambridge University Press 2000)

- Clark, Ward M. Misplaced Compassion: The Animal Rights Movement Exposed, Writer's Club Press, 2001

- Dawkins, Richard. Gaps in the mind.

- Dunayer, Joan. "Animal Equality, Language and Liberation" 2001

- Francione, Gary. Introduction to Animal Rights, Your child or the dog?, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000

- Kean, Hilda. Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800, London: Reaktion Books, 1998

- Nibert, David. Animal Rights, Human Rights: Entanglements of Oppression and Liberation, New York: Rowman and Litterfield, 2002

- Patterson, Charles. Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust. New York: Lantern, 2002. ISBN 1-930051-99-9

- Ryder, Richard. D. Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes towards Speciesism, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989

- Scruton, Roger. Animal Rights and Wrongs Claridge Press, 2000

- Singer, Peter, "Animal Liberation".

- Spiegal, Marjorie. The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery, New York: Mirror Books, 1996.

- Steeve, Peter H. (ed.) Animal Others: On Ethics, Ontology, and Animal Life. New York: SUNY Press, 1999.

- Taylor, Angus. Animals and Ethics. Broadview Press, 2003

- Weil, Zoe. The Power and Promise of Humane Education. British Columbia: New Society Publishers, 2004.

- Wolfe, Cary. Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory, Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 2003.

- Wolch, Jennifer, & Emel, Jody. Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands. New York: Verso, 1998.

Animal rights in philosophy and law

- The National Association for Biomedical Research Animal Law Section.

- The Tom Regan Animal Rights Archive.

- Utilitarian Philosophers: Peter Singer.

- Animal Law Project.

- animal-rights.de.

- Ethical foundations of animal rights

- The Animal Rights Library

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on The Moral Status of Animals

- The Center on Animal Liberation Affairs (CALA)

- Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF).

Animal rights resources

- An Animal-Friendly Life Animal Rights News, Commentary, Podcasting, Links & Other Resources

- Animal People Animal protection news and investigative reporting

- Animal Rights News & Resources (Northern California and beyond)

- Animal Rights Resources

- Animal Rights Concerns

- Anesthesia's Wonderland

- Animal Voices Radio Show A Canadian based radio program with full archieves of past shows on their website for free download. Show features interviews with prominent organizations, authors, and activists from across the globe. Show also covers topics relating to social justice (for example, feminism, anti-racism, and critiques of capitalism) as well as critical environmental theory and praxis as they relate to animal issues.

- Of Human and Non-Human Animals Animal issues debates, news, reflections, putting them into a wider political arena. Ethical and political foundations of an animal movement.

- Satya Magazine A Magazine of Vegetarianism, Animal Rights and Social Justice

- VegNews Magazine

- Vegan Voice Magazine

- [9] poems about animal rights

Animal rights organizations

- Action for Animals

- Animal Aid

- Animal Liberation Victoria (ALV)

- Animal Liberation (Maqi)

- Animal Protection Institute (API)

- Animal Rights Kollective (ARKII) - Canada

- Animal Rights International (ARI)

- BarryHorne.org

- Center on Animal Liberation Affairs (CALA)

- Jewish Vegetarians of North America

- Christian Vegetarian Association (CVA)

- Compassion Over Killing (COK)

- Compassionate Action for Animals

- The Fund for Animals

- Hunt Saboteurs Association

- Humane Society of the United States (HSUS)

- In Defense of Animals (IDA)

- Madison's Hidden Monkeys

- Mercy for Animals

- New England Anti-Vivisection Society (NEAVS)

- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA)

- Primate Freedom Project (PFP)

- Protecting Animals USA

- Rights for Animals

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)

- Society of Ethical & Religious Vegetarians (SERV)

- SPEAK

- Toronto Animal Rights Society - Canada

- United Poultry Concerns (UPC)

- Vegan Outreach

- French Animal Rights League

Animal rights online community

- VeggieBoards (message board and recipes)

- Peta2 (Question Reality Question Authority)

- International Animal Rights Community (ARCo)

- Vegan Porn: News and Information for Vegans Who Get It - A busy, Canadian-based message board which is not actually about pornography at all but rather a creative way to get into Google search listings

Animal rights directories

Animal rights critics

- PETA Kills Animals

- National Animal Interest Aliance

- Center for Consumer Freedom: Take a Bite out of PETA A petition to have PETA's Tax-exempt status revoked

- Animal Rights Hunting Page

Dealing with animal rights critics

- "The Center for Consumer Freedom" Exposed A website that aims to expose the owner of sites like “Peta kills animals”.

Humane-education organizations

- Bridges of Respect Building Bridges Between Humans, Animals and Environment

- Canadian Federation of Humane Societies Humane Education Program

- Circle of Compassion Exploring Peaceable Choices for the Planet and All those that Share

- The Empathy Project Inspiring Empathy for Humans, Animals, and the Planet

- Ethical Science & Education Coalition (ESEC)

- Healing Earth Education

- The Institute for Animal Associated Lifelong Learning Interrelating people, nonhuman animals, and the earth through education

- International Institute for Humane Education Formerly known as the Center for Compassionate Living

- Kind Planet

- National Association of Environmental and Humane Education

- New World Vision: Creating a Compassionate, Peaceful, Sustainable World Through Humane Education

- Seeds for Change Humane Education

- TeachKind

Ethical concerns

- Which animals feel pain?

- Anima-Ethic for Animal Rights

- Animals and other living things: their interests, mental capacities and moral entitlements

- Taking Animals Seriously: Mental Life and Moral Status by David DeGrazia - A Review Essay

- Animal slavery

- Eco-Eating: Eating as if the Earth Matters

- Cruelty to Animals @ the Catholic Encyclopedia

Animal welfare organizations

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.