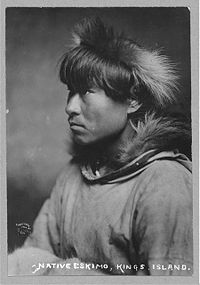

Eskimo

Eskimos or Esquimaux is a term referring to aboriginal people who inhabit the circumpolar region, excluding Scandinavia and most of Russia, but including the easternmost portions of Siberia. There are two main groups of Eskimos: the Inuit of northern Alaska, Canada and Greenland, and the Yupik, comprising speakers of four distinct Yupik languages and originating in western Alaska, in southcentral Alaska along the Gulf of Alaska coast, and in the Russian Far East.

Terminology

The term Eskimo is broadly inclusive of the two major groups, the Inuit—including the Kalaallit (Greenlanders) of Greenland, Inuit and Inuinnait of Canada, and Inupiat of northern Alaska—and the Yupik peoples—the Naukan of Siberia, the Siberian Yupik of Siberia in Russia and St. Lawrence Island in Alaska, the Central Alaskan Yup'ik of Alaska, and the Alutiiq (Sug'piak or Pacific Eskimo) of southcentral Alaska.

However, in Canada and Greenland, Eskimo is widely considered pejorative and offensive, and has been replaced overall by Inuit. The preferred term in Canada's Central Arctic is Inuinnait, and in the eastern Canadian Arctic Inuit. The language is often called Inuktitut, though other local designations are also used. The Inuit of Greenland refer to themselves as Greenlanders or, in their own language, Kalaallit, and to their language as Greenlandic or Kalaallisut.[1]

Because of the linguistic, ethnic, and cultural differences between Yupik and Inuit languages and peoples, there is still uncertainty as to what term encompassing all Yupik and Inuit people will be acceptable to all. There has been some movement to use Inuit as a term encompassing all peoples formerly described as Eskimo, Inuit and Yupik alike. The Inuit Circumpolar Conference, representing a circumpolar population of 150,000 Inuit and Yupik people of Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia, defines Inuit in its charter as including "the Inupiat, Yupik (Alaska), Inuit, Inuvialuit (Canada), Kalaallit (Greenland) and Yupik (Russia)."[2] Strictly speaking, however, Inuit refers only to the Inupiat of northern Alaska, the Inuit of Canada, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, but not to the Yupik peoples or languages of Alaska and Siberia. This is because the Yupik languages are linguistically distinct from the Inupiaq and other Inuit languages, and the peoples are ethnically and culturally distinct as well. The word Inuit does not occur in the Yupik languages of Alaska and Siberia.[1]

Thus, in Alaska, Eskimo continues to be acceptable, and is the preferred term when speaking collectively of all Inupiaq and Yupik people, or of all Inuit and Yupik people of the world.[1] Alaskans also use the term Alaska Native, though this term is also inclusive of Aleut and Indians people of Alaska, and is of course exclusive of Inuit or Yupik people originating outside the state. The term has important legal usage in Alaska and the rest of the United States as a result of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971.

The term "Eskimo" is also used in some linguistic or ethnographic works to denote the larger branch of Eskimo-Aleut languages, the smaller branch being Aleut. In this usage, Inuit (together with Yupik, and possibly also Sireniki), are sub-branches of the Eskimo language family. See details in articles Eskimo and Eskimo-Aleut languages.

Origin of the term Eskimo

Some Algonquian languages call Eskimos by names that mean "eaters of raw meat" or something that sounds similar. The Plains Ojibwe, for example, use the word êškipot ("one who eats raw," from ašk-, "raw," and -po-, "to eat") to refer to Eskimos. It is entirely possible that the Ojibwe have adopted words resembling "Eskimo" by borrowing them from French, and the French word merely sounds like Ojibwe words that can be interpreted as "eaters of raw meat."

But in the period of the earliest attested French use of the word, the Plains Ojibwe were not in contact with Europeans, nor did they have very much direct contact with the Inuit in pre-colonial times.

The Innu-aimun (Montagnais) language, a dialect of Cree which was known to French traders at the time of the earliest attestation of esquimaux, does not have vocabulary fitting this etymological analysis. Furthermore, since Cree people also traditionally consumed raw meat, a pejorative significance based on this etymology seems unlikely. A variety of competing etymologies have been proposed over the years, but the most likely source is the Montagnais word meaning "snowshoe-netter." Since Montagnais speakers refer to the neighbouring Mi'kmaq people using words that sound very much like eskimo, many researchers have concluded that this is the more likely origin of the word.[3][4][5]

The anthropologist Thomas Huxley in On the Methods and Results of Ethnology (1865) defined the "Esquimaux race" to be the indigenous peoples in the Arctic region of northern Canada and Alaska. He described them to "certainly present a new stock" (different from the other indigenous peoples of North America). He described them to have straight black hair, dull skin complexion, short and squat, with high cheek bones and long skulls.

Main Ethnic Groups

Inuit

The Inuit inhabit the Arctic and Bering Sea coasts of Siberia and Alaska and Arctic coasts of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Quebec, Labrador, and Greenland. Until fairly recent times, there has been a remarkable homogeneity in the culture throughout this area, which traditionally relied on fish, sea mammals, and land animals for food, heat, light, clothing, tools, and shelter.

Canada's Inuit

Canadian Inuit live primarily in Nunavut (a territory of Canada), Nunavik (the northern part of Quebec) and in Nunatsiavut (the Inuit settlement region in Labrador).

Inupiat

The Inupiat or Inupiaq people are the Inuit people of Alaska's Northwest Arctic and North Slope boroughs and the Bering Straits region, including the Seward Peninsula. Barrow, the northernmost city in the United States, is in the Inupiaq region. Their language is known as Inupiaq.

Inuvialuit

The Inuvialuit live in the western Canadian Arctic region. They are descendants of the Thule people, of which other descendants inhabit Russia and parts of Scandinavia. Their homeland - the Inuvialuit Settlement Region - covers the Arctic Ocean coastline area from the Alaskan border east to Amundsen Gulf and includes the western Canadian Arctic Islands. The land was demarked in 1984 by the Inuvialuit Final Agreement.

Kalaallit

The Kalaallit live in Greenland, which is called Kalaallit Nunaat in Kalaallisut.

Yupik

The Yupik are indigenous or aboriginal peoples who live along the coast of western Alaska, especially on the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta and along the Kuskokwim River (Central Alaskan Yup'ik), in southern Alaska (the Alutiiq) and in the Russian Far East and St. Lawrence Island in western Alaska (the Siberian Yupik).

Alutiiq

The Alutiiq also called Pacific Yupik or Sugpiaq, are a southern, coastal branch of Yupik. They are not to be confused with the Aleuts, who live further to the southwest, including along the Aleutian Islands. They traditionally lived a coastal lifestyle, subsisting primarily on ocean resources such as salmon, halibut, and whale, as well as rich land resources such as berries and land mammals. Alutiiq people today live in coastal fishing communities, where they work in all aspects of the modern economy, while also maintaining the cultural value of subsistence. The Alutiiq language is relatively close to that spoken by the Yupik in the Bethel, Alaska area, but is considered a distinct language with two major dialects: the Koniag dialect, spoken on the Alaska Peninsula and on Kodiak Island, and the Chugach dialect, is spoken on the southern Kenai Peninsula and in Prince William Sound. Residents of Nanwalek, located on southern part of the Kenai Peninsula near Seldovia, speak what they call Sugpiaq and are able to understand those who speak Yupik in Bethel. With a population of approximately 3,000, and the number of speakers in the mere hundreds, Alutiiq communities are currently in the process of revitalizing their language.

Central Alaskan Yup'ik

Yup'ik, with an apostrophe, denotes the speakers of the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, who live in western Alaska and southwestern Alaska from southern Norton Sound to the north side of Bristol Bay, on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, and on Nelson Island The use of the apostrophe in the name Yup'ik denotes a longer pronunciation of the p sound than found in Siberian Yupik. Of all the Alaska Native languages, Central Alaskan Yup'ik has the most speakers, with about 10,000 of a total Yup'ik population of 21,000 still speaking the language. There are five dialects of Central Alaskan Yup'ik, including General Central Yup'ik and the Egegik, Norton Sound, Hooper Bay-Chevak, Nunivak, dialects. In the latter two dialects, both the language and the people are called Cup'ik.[6]

Siberian Yupik (Yuit)

Siberian Yupik reside along the Bering Sea coast of the Chukchi Peninsula in Siberia in the Russian Far East[7] and in the villages of Gambell and Savoonga on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska.[8] The Central Siberian Yupik spoken on the Chukchi Peninsula and on St. Lawrence Island is nearly identical. About 1,050 of a total Alaska population of 1,100 Siberian Yupik people in Alaska still speak the language, and it is still the first language of the home for most St. Lawrence Island children. In Siberia, about 300 of a total of 900 Siberian Yupik people still learn the language, though it is no longer learned as a first language by children.[8]

Naukan

About 70 of 400 Naukan people still speak the Naukanski. The Naukan originate on the the Chukot Peninsula in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in Siberia.[7]

Culture

Eskimo groups comprise a huge area stretching from Eastern Siberia through Alaska and Northern Canada (including Labrador Peninsula) to Greenland. Important examples of shamanistic practice and beliefs have been recorded at several parts of this vast area crosscutting continental borders.[9][10][11]

Do the belief systems of various Eskimo groups have such common features that justifies speaking about “Eskimo” belief systems? There is a certain unity in the cultures of the Eskimo groups.[12][13] Although a large distance separated the Asiatic Eskimos and Greenland Eskimos, their shamanistic seances showed many similarities.[14] Similar remarks apply for comparisons of Asiatic with North American Eskimo shamanisms.[15] Also the usage of a specific shaman's language is documented among several Eskimo groups,[10][9] including Asian ones.[16]

Similar remarks apply for aspects of the belief system not directly linked to shamanism:

- tattooing[17]

- accepting the killed game as a dear guest visiting the hunter[18]

- usage of amulets[19]

- lack of totem animals[20][21]

Languages

The term Eskimo has fallen out of favour in Canada and Greenland, where it is considered pejorative and the term Inuit has become more common. However, the term Eskimo is still considered acceptable among Alaska Natives of Yupik and Inupiaq (Inuit) heritage, and is preferred over Inuit as a collective reference. To date, no replacement term for Eskimo inclusive of all Inuit and Yupik people has achieved acceptance across the geographical area inhabited by the Inuit and Yupik peoples.

The Inuit and Yupik peoples are related to the Aleuts from the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. The Eskimo languages, together with the Aleut language, comprise the Eskimo-Aleut language group.

The Sireniki language is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family, but other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.[7]

Inuit languages comprise a dialect continuum, or dialect chain, that stretches from Unalaska and Norton Sound in Alaska, across northern Alaska and Canada, and east all the way to Greenland. Changes from western (Inupiaq) to eastern dialects are marked by the dropping of vestigial Yupik-related features, increasing consonant assimilation (e.g., kumlu, meaning "thumb," changes to kuvlu, changes to kullu), and increased consonant lengthening, and lexical change. Thus, speakers of two adjacent Inuit dialects would usually be able to understand one another, but speakers from dialects distant from each other on the dialect continuum would have difficulty understanding one another.[7]

The four Yupik languages, including Alutiiq (Sugpiaq), Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Naukan (Naukanski), and Siberian Yupik are distinct languages with phonological, morphological, and lexical differences, and demonstrating limited mutual intelligibility. Additionally, both Alutiiq Central Yup'ik have considerable dialect diversity. The northernmost Yupik languages—Siberian Yupik and Naukanski Yupik—are linguistically only slightly closer to Inuit than is Alutiiq, which is the southernmost of the Yupik languages. Although the grammatical structures of Yupik and Inuit languages are similar, they have pronounced differences phonologically, and differences of vocabulary between Inuit and any of one of the Yupik languages is greater than between any two Yupik languages.[7]

The Sireniki language is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family, but other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.[7]

An overview of the Eskimo-Aleut languages family is given below:

- Aleut

- Aleut language

- Western-Central dialects: Atkan, Attuan, Unangan, Bering (60-80 speakers)

- Eastern dialect: Unalaskan, Pribilof (400 speakers)

- Aleut language

- Eskimo (Yup'ik, Yuit, and Inuit)

- Central Alaskan Yup'ik (10,000 speakers)

- Alutiiq or Pacific Gulf Yup'ik (400 speakers)

- Central Siberian Yupik or Yuit (Chaplinon and St Lawrence Island, 1400 speakers)

- Naukan (70 speakers)

- Inuit or Inupik (75,000 speakers)

- Iñupiaq (northern Alaska, 3,500 speakers)

- Inuvialuktun or Inuktun (western Canada; 765 speakers)

- Inuktitut (eastern Canada; together with Inuktun and Inuinnaqtun, 30,000 speakers)

- Kalaallisut (Greenland, 47,000 speakers)

- Sirenik (extinct)

Religion

Shamanism among Eskimo peoples refers to those aspects of the various Eskimo cultures that are related to the shamans’ role as a mediator between people and spirits, souls, and mythological beings. Such beliefs and practices were once widespread among Eskimo groups, but today are rarely practiced,[23] and it was already in the decline among many groups even in the times when the first major ethnological researches were done,[24] just an example: among Polar Eskimos, in the end of 19the century, Sagloq died, the last shaman who was believed to be able to travel to the sky and under the sea—and many other former shamanic capabiblities went lost even in that time as well (ventriloquism, sleight-of-hand).[25]

The term “shamanism” has been used for various distinct cultures. Classically, some indigenous cultures of Siberia were described as having shamans, but the term is now commonly used for other cultures as well. In general, the shamanistic belief systems accept that certain people (shamans) can act as mediators with the spirit world,[26] contacting the various entities (spirits, souls, and mythological beings) that populate the universe in those systems.

Shamans use various means, including music, recitation of epic, dance, and ritual objects[27] to interact with the spirit world - either for the benefit of the community or for doing harm. They may have spirits that assist them and may also travel to other worlds (or other aspects of this world). Most Eskimo groups had such a mediator function,[28] and the person fulfilling the role was believed to be able to command helping spirits, ask mythological beings (e.g. Nuliayuk among the Netsilik Inuit and Takanaluk-arnaluk in Aua's narration) to “release” the souls of animals, enable the success of the hunt, or heal sick people by bringing back their “stolen” souls. Shaman is used in an Eskimo context in a number of English-language publications, both academic[9][10] and popular,[15] generally in reference to the angakkuq among the Inuit. The /aˈliɣnalʁi/ of the Siberian Yupiks is also translated as “shaman” in both Russian and English literature.[29][30]

Shamanism among the Eskimo peoples exhibits some characteristic features not universal in shamanism, such as a dualistic concept of the soul in certain groups, and specific links between the living, the souls of hunted animals and dead people.[31] The death of either a person or a game animal requires that certain activities, such as cutting and sewing, be avoided to prevent harming their souls. In Greenland, the transgression of this death taboo could turn the soul of the dead into a tupilak, a restless ghost which scared game away. Animals were thought to flee hunters who violated taboos.[32]

Shamanic intiation

Unlike many Siberian traditions, in which spirits force individuals to become shamans, most Eskimo shamans choose this path.[33] Even when someone receives a “calling,” that individual may refuse it.[34] The process of becoming an Eskimo shaman usually involves difficult learning and initiation rites, sometimes including a vision quest. Like the shamans of other cultures, some Eskimo shamans are believed to have special qualifications: they may have been an animal during a previous period, and thus be able to use their valuable experience for the benefit of the community.[35][15][36]

The initiation process varies from culture to culture. It may include:

- a specific kind of vision quest, such as among the Chugach.

- various kinds of out-of-body experiences such seeing oneself as skeleton, exemplified in Aua's (Iglulik) narration and a Baker Lake artwork[37][38]

Shamanic Language

In several groups, shamans utilized a distinctly archaic version of the normal language interlaced with special metaphors and speech styles. Expert shamans could speak whole sentences differing from vernacular speech.[39] In some groups such variants were used when speaking with spirits invoked by the shaman, and with unsocialised babies who grew into the human society through a special ritual performed by the mother. Some writers have treated both phenomena as a language for communication with “alien” beings (mothers sometimes used similar language in a socialization ritual, in which the newborn is regarded as a little “alien” - just like spirits or animal souls).[40] The motif of a distinction between spirit and “real” human is also present in a tale of Ungazigmit (subgroup of Siberian Yupik)[41]

| “ | The oldest man asked the girl: “What, are you not a spirit?” The girl answered: “I am not a spirit. Probably, are you spirits?” The oldest man said: “We are not spirits, [but] real human” | ” |

Soul dualism

The Eskimo shaman may fulfill multiple functions, including healing, curing infertile women, and securing the success of hunts. These seemingly unrelated functions can be grasped better by understanding the concept of soul dualism which, with some variation, underlies them.

- Healing

- It is held that the cause of sickness is soul theft, in which someone (perhaps an enemy shaman or a spirit) has stolen the soul of the sick person. The person remains alive because people have multiple souls, so stealing the appropriate soul causes illness or a moribund state rather than immediate death. It takes a shaman to retrieve the stolen soul.[42] According to another variant among Ammassalik Eskimos in East Greenland, the joints of the body have their own small souls, the loss of which causes pain.[11]

- Fertility

- The shaman provides assistance to the soul of an unborn child to allow its future mother to become pregnant.[43]

- Success of hunts

- When game is scarce the shaman can visit a mythological being who protects all sea creatures (usually the Sea Woman Sedna). Sedna keeps the souls of sea animals in her house or in a pot. If the shaman pleases her, she releases the animal souls thus ending the scarcity of game.[9]

It is the shaman's free soul that undertakes these spirit journeys (to places such as the land of dead, the home of the Sea Woman, or the moon) whilst his body remains alive.[43] When a new shaman is first initiated, the initiator extracts the shaman's free soul and introduces it to the helping spirits so that they will listen when the new shaman invokes them[44]; or according to an another explanation (that of the Iglulik shaman Aua) the souls of the vital organs of the apprentice must move into the helping spirits: the new shaman should not feel fear of the sight of his new helping spirits.[45]

Animals may have souls that are shared across their species.[10] A human child's developing soul is usually “supported” by a name-soul: a baby can be named after a deceased relative, invoking the departed name-soul which will then accompany and guide the child until adolescence. This concept of inheriting name-souls amounts to a sort of reincarnation among some groups, such as the Caribou Eskimos.[9]

Social position

The boundary between shaman and lay person was not always clearly demarcated. Non-shamans could also experience hallucinations,[46][47] almost every Eskimo may report memories about ghosts, animals in human form, little people living in remoted places.[48] Experiences such as hearing voices from ice or stones were discussed as readliy as everyday hunting adventures.[49] The ability to have and command helping spirits was characteristic of shamans, but non-shamans could also profit from spirit powers through the use of amulets. In one extreme instance a Netsilingmiut child had eighty amulets for protection.[50][51]

Secrecy and Publicity

It was believed in several contexts that secrecy or privacy may be needed for an act or an object (either beneficial or harmful, intended or incidental) to be effective, and that publicity may neutralize its effects.

- Magic formulae usually required secrecy and could lose their power if they became known by other people than their owners.

- Deliberately harmful magical acts (ilisiinneq) had to be done in secrecy.

- If the victim of another detrimental magical act (tupilak-making) had enough magical power (for example through amulets) to notice the act and “rebound” it back to the perpetrator, the endangered person could escape retribution only by public confession of his planned (and failed) sorcery.

- a rite of passage celebrating the first major hunting success of a boy often contained a “partaking” element: the whole community cut the dead animal or took part in its consumption. The function of this rite was to establish a positive relationship between the young man and the game animal; because the killed animal could bring danger to the hunter, this ritual lessened the danger by sharing the responsibility.

Some of the shaman's functions can be understood in the light of this notion of secrecy versus publicity. The cause of illness was usually believed to be soul theft or a breach of some taboo (such as miscarriage). Public confession (lead by the shaman during a public seance) could bring relief to the patient. Similar public rituals were used in the cases of taboo breaches that endangered the whole community (bringing the wrath of mythical beings causing calamities).[9]

Contemporary Eskimo

Eskimos throughout the U.S. and Canada live in largely settled communities, working for corporations and unions, and have come to embrace other cultures and contemporary conveniences in their lifestyle. Although still self-sufficient through their time-honored traditions of fishing and hunting, the Eskimos are no longer completely dependent on their own arctic resources. Many have adopted the use of modern technology in the way of snowmobiles instead of dog sleds, and modern houses instead of igloos. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 granted Alaska natives some 44 million acres of land and established native village and regional corporations to encourage economic growth. In 1990 the Eskimo population of the United States was approximately 57,000, with most living in Alaska. There are over 33,000 Inuit in Canada (the majority living in Nunavut), the Northwest Territories, N Quebec, and Labrador. Nunavut was created out of the Northwest Territories in 1999 as a predominately Inuit territory, with political seperation. A settlement with the Inuit of Labrador established (2005) Nunatsiavut, which is a self-governing area in N and central E Labrador. There are also Eskimo populations in Greenland and Siberia.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kaplan, Lawrence. (2002). "Inuit or Eskimo: Which names to use?". Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Retrieved on 2007-04-06.

- ↑ Inuit Circumpolar Conference. (2006). "Charter." Inuit Circumpolar Conference (Canada). Retrieved on 2007-04-06.

- ↑ Mailhot, J. (1978). "L'étymologie de «Esquimau» revue et corrigée." Etudes Inuit/Inuit Studies 2-2:59-70.

- ↑ Goddard, Ives (1984). "Synonymy." In Arctic, ed. David Damas. Vol. 5 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant, pp. 5-7. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Cited in Campbell 1997

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America, pg. 394. New York: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Alaska Native Language Center. (2001-12-07). "Central Alaskan Yup'ik." Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Anchorage. Retrieved on 2007-04-06.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Kaplan, Lawrence. (2001-12-10). "Comparative Yupik and Inuit". Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Retrieved on 2007-04-06.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Alaska Native Language Center. (2001-12-07). "Siberian Yupik." Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Anchorage. Retrieved on 2007-04-06.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Kleivan 1985 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "KleiSon-Esk" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Merkur 1985

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gabus 1970:18,122 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Gabus" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Rasmussen 1926

- ↑ Mauss 1979

- ↑ Menovščikov 1996 [1968]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Vitebsky 2001 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Vit-Sam" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Vit-Sam" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Rubcova 1954, pg. 128

- ↑ Tattoos of the early hunter-gatherers of the Arctic written by Lars Krutak

- ↑ Rubcova 1954, pg. 218

- ↑ Rubcova 1954, pg. 380

- ↑ (Russian) A radio interview with Russian scientists about Asian Eskimos

- ↑ Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1952) The Sociological Theory of Totemism. In Structure and Function in Primitive Society. Glencoe: The Free Press.

- ↑ Fienup-Riordan, Ann. (1994). Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 206.) Nushagak, located on Nushagak Bay of the Bering Sea in southwest Alaska, is part of the territory of the Yup'ik, speakers of the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language.

- ↑ Merkur 1985:4

- ↑ Merkur 1985:132

- ↑ Merkur 1985:134

- ↑ Hoppál 2005:45–50

- ↑ Hoppál 2005:14

- ↑ Menovščikov 1968:442

- ↑ Rubcova 1954, pp. 203–19

- ↑ Menovščikov 1968, p. 442

- ↑ Vitebsky 1996:14

- ↑ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:12–13, 18–21, 23

- ↑ Diószegi 1962

- ↑ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:24

- ↑ Barüske, Heinz. 1969. “Die Seele, die alle Tiere durchwanderte,” in Eskimo Märchen, 19–23 (tale 7). Düsseldorf: Eugen Diederichs.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Knud, ed. and coll. 1921 “The Soul that Lived in the Bodies of All Beasts,” in Eskimo Folk-Tales, ed. and trans. W. Worster, with illustrations by native Eskimo artists, 100. London: Gyldendal.

- ↑ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:38, plate XXIII

- ↑ Vitebsky 1996:18

- ↑ Merkur 1985:7

- ↑ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:6,14,33

- ↑ Rubcova 1954, p. 175 (34)–(38)

- ↑ Rasmussen 1965:177

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Merkur 1985, p. 4

- ↑ Merkur 1985:121

- ↑ Rasmussen 1965:170

- ↑ Merkur 1985:41–42

- ↑ Gabus 1970:18,122

- ↑ Merkur 1985:41

- ↑ Gabus 1970:203

- ↑ Kleivan & Sonne:43

- ↑ Rasmussen 1965: 262

References

- Diószegi, Vilmos (1962). Samanizmus, Élet és Tudomány Kiskönyvtár.

- Gabus, Jean (1970). A karibu eszkimók. Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó. Translation of the original: (1944) Vie et coutumes des Esquimaux Caribous. Libraire Payot Lausanne.

- Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3. (The title means “Shamans in Eurasia,” the book is written in Hungarian, but it is also published in German, Estonian and Finnish). Site of publisher with short description on the book (in Hungarian)

- Kleivan, I. and B. Sonne (1985). Eskimos: Greenland and Canada, Iconography of religions, section VIII, "Artic Peoples," fascicle 2. Leiden, The Netherlands: Institute of Religious Iconography • State University Groningen. E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-07160-1.

- Mauss, Marcel [c1950] (1979). Seasonal variations of the Eskimo: a study in social morphology, in collab. with Henri Beuchat; translated, with a foreword, by James J. Fox, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Menovščikov, G. A. (Г. А. Меновщиков). Popular Conceptions, Religious Beliefs and Rites of the Asiatic Eskimoes. Translated into English and published in: Diószegi, Vilmos and Mihály Hoppál [1968] (1996). Folk Beliefs and Shamanistic Traditions in Siberia. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Merkur, Daniel (1985). Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Rasmussen, Knud (1926). Thulefahrt. Frankfurt am Main: Frankurter Societăts-Druckerei.

- Rasmussen, Knud (1965). Thulei utazás, transl. Detre Zsuzsa, Világjárók (in Hungarian), Budapest: Gondolat. Hungarian translation of Rasmussen 1926.

- Rubcova, E. S. (1954). Materials on the Language and Folklore of the Eskimoes (Vol. I, Chaplino Dialect). Moscow • Leningrad: Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Original data: Рубцова, Е. С. (1954). Материалы по языку и фольклору эскимосов (чаплинский диалект). Москва • Ленинград: Академия Наук СССР.

- Vitebsky, Piers (2001). The Shaman: Voyages of the Soul - Trance, Ecstasy and Healing from Siberia to the Amazon. Duncan Baird. ISBN 1-903296-18-8.

- Vitebsky, Piers (1996). A sámán, Bölcsesség • hit • mítosz. Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub • Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963 208 361 X. Translation of the original: (1995) The Shaman (Living Wisdom). Duncan Baird.

- Voigt, Miklós (2000). Világnak kezdetétől fogva / Történeti folklorisztikai tanulmányok (in Hungarian). Budapest: Universitas Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963 9104 39 6. In it, on pp 41–45: Sámán—a szó és értelme (The etymology and meaning of word shaman).

External links

- The Asiatic (Siberian) Eskimos

- Eskimo Music

- Origin of the word "Eskimo"

- American Heritage Dictionary: Eskimo

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Frank H. Nowell Photographs Photographs documenting scenery, towns, businesses, mining activities, Native Americans, and Eskimos in the vicinity of Nome, Alaska from 1901-1909.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Alaska and Western Canada Collection Images documenting Alaska and Western Canada, primarily the provinces of Yukon Territory and British Columbia depicting scenes of the Gold Rush of 1898, city street scenes, Eskimo and Native Americans of the region, hunting and fishing, and transportation.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Arthur Churchill Warner Photographs Includes images of Eskimos from 1898-1900.

- Did Eskimos put their elderly on ice floes to die? article by Straight Dope Science Advisory Board

- Духовная культура (Spiritual culture), subsection of Support for Siberian Indigenous Peoples Rights (Поддержка прав коренных народов Сибири)—see the section on Eskimos

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.