Difference between revisions of "Celts" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) (copied from wikipedia) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The term '''Celt''', normally pronounced /{{IPA|kɛlt}}/ (see [[Pronunciation of Celtic|article on pronunciation]]), now refers primarily to a member of any of a number of peoples in [[Europe]] using the [[Celtic languages]], which form a branch of the [[Indo-European languages]]. It can refer in a wider sense to a user of [[celtic culture]]. However, in ancient times the term 'celt' was used either to refer generally to [[barbarian]]s in north-western Europe or to specific groups of tribes in the [[Iberian Peninsula]] and [[Gaul]]. The focus of this article is the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe, for the Celts of the present day see [[Modern Celts]]. | |

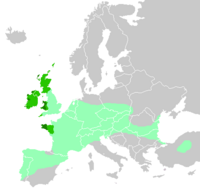

| − | + | Although today restricted to the [[Atlantic Ocean|Atlantic]] coast of Western Europe, the so-called "Celtic fringe," Celtic languages were once predominant over much of Europe, from [[Ireland]] and the [[Iberian Peninsula]] in the west to northern [[Italy]] and [[Serbia]] in the east. Archaeological and historical sources show that at their maximum extent in the third century B.C.E., Celtic peoples were also present in areas of [[Eastern Europe]] and [[Asia Minor]]. | |

| − | + | ==Overview== | |

| + | The term '''Celt''' has been adopted as a label of self-identity for a variety of peoples at different times. However, it does not seem to have been used to refer to Celtic language speakers as a whole before the 18th century. In ancient times it was primarily used by Greeks and Romans as a label for groups of people who were distinguished from others by cultural characteristics. | ||

| − | In the last two decades of the twentieth century multidisciplinary studies were brought to bear on the history of the Celts. Disciplines such as ancient history, palaeolinguistics, archaeology, history of art, anthropology, population genetics, history of religion, ethnology, mythology and folklore studies all had an influence on celtic studies. | + | '''Celticity''' refers to the concept which links these peoples. Historically, theories were developed that similar language, material artifacts, social organisation and mythological factors were indicative of a common racial origin, but later theories of culture spreading to differing [[indigenous peoples]] have discredited these theories.{{Fact|date=June 2007}} The current concept of a common cultural heritage has recently been supported by some genetic studies which show that populations consist of people with many origins.{{Fact|date=June 2007}} The Celtic culture seems to have had numerous diverse characteristics, thus the only commonality between these diverse peoples was the use of one of the [[Celtic languages]]. |

| + | |||

| + | The term '''Celtic''' as a noun means the family of languages but as an adjective it has the meaning "of the Celts" or "in the style of the Celts." The article on [[Celtic (disambiguation)|Celtic]] links to a number of applications of this term. It has also been used to refer to several archaeological cultures, defined by unique sets of artifacts. The link between language and artifacts is nothing more than assumption unless inscriptions are present. Thus the term '''Celtic''' is reserved by linguists for the language family but is commonly used to denote both linguistic and cultural groups. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Celts themselves had an intricate, indigenous [[Celtic polytheism|polytheistic religion]] and distinctive material and social culture. In the Iron Age they were spread from the Iberian Peninsula to Turkey and ancient Iberia at Caucasus, but their [[urheimat]] is a matter of controversy. Traditionally, scholars have placed the Celtic homeland in what is now southern Germany and Austria, associating the earliest Celtic peoples with the [[Hallstatt culture]]. However, modern linguistic studies seem to point to a north Balkan origin. The expansion of the [[Roman Empire]] from the south and the [[Germanic tribes]] from the north and east spelt the end of Celtic culture on the European mainland where [[Brittany]] alone maintained its Celtic language and identity, probably due to later immigrants from Great Britain. Julius Caesar described the term "Celt" as the word used by the people of central France (only) to refer to themselves, the Roman name being Gauls.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} The known names of Celtic peoples are given in the list of [[Celtic tribes]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The eventual development of [[Celtic Christianity]] in [[Ireland]] and [[Britain]] brought an early [[medieval]] renaissance of [[Celtic art]] between 400 and 1200, only ended by the [[Norman Conquest]] of Ireland in the late [[12th century]]. Notable works produced during this period include the [[Book of Kells]] and the [[Ardagh Chalice]]. [[Antiquarian]] interest from the [[17th century]] led to the term '''Celt''' being extended, and rising [[nationalism]] brought Celtic revivals from the [[19th century]] in areas where the use of Celtic languages had continued. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Today, the term '''Celtic''' is often used to describe the languages and respective cultures of [[Ireland]], [[Scotland]], [[Wales]], [[Cornwall]], the [[Isle of Man]] and [[Brittany]], regions where four [[Celtic languages]] are still spoken by minorities today as mother tongues, [[Irish language|Irish Gaelic]], [[Scottish Gaelic language|Scottish Gaelic]], [[Welsh people|Welsh]], and [[Breton language|Breton]] plus two recent revivals, [[Cornish language|Cornish]] (one of the [[Brythonic language]]s) and [[Manx language|Manx]] (one of the [[Goidelic languages]]). It is also used for other regions from the [[Continental Europe]] of Celtic heritage, but where no [[Celtic language]] has survived, which include the northern [[Iberian Peninsula]] (northern [[Portugal]], and the [[Autonomous communities of Spain|Spanish historical regions]] of [[Galicia]], [[Asturias]] and [[Cantabria]]), and in a lesser degree, [[France]]. ''(see the [[Modern Celts]] article)'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The term '''Continental Celt''' refers to the celtic speaking people of mainland Europe, excluding Brittany which is a special case. The term '''insular celt''' refers to the people of Britain and Ireland. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The term '''Atlantic Celt''' had been introduced to refer to people in Iberia, France, Ireland and Britain with a celtic heritage. However, it has been asserted that since the assumption that there is a genetic link between Atlantic and Continental Celts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the last two decades of the twentieth century, multidisciplinary studies were brought to bear on the history of the Celts. Disciplines such as [[ancient history]], palaeolinguistics, [[historical linguistics]], archaeology, [[history of art]], anthropology, population genetics, history of religion, ethnology, mythology and folklore studies all had an influence on [[Celtic Studies|celtic studies]]. | ||

==Development of the term "Celt"== | ==Development of the term "Celt"== | ||

| − | The first literary reference to the Celtic people, as '' | + | ===Ancient uses=== |

| + | The first literary reference to the Celtic people, as Κελτοί (''Κeltoi'') is by the [[Greece|Greek]] [[historian]] [[Hecataeus]] in 517 B.C.E.; he locates the ''Keltoi'' tribe in Rhenania (West/Southwest Germany). The next Greek reference to the ''Keltoi'' is by [[Herodotus]] in the mid 5th century. He says that "the river Ister [Danube] begins from the ''Keltoi'' and the city of Pyrene and so runs that it divides Europe in the midst (now the ''Keltoi'' are outside the Pillars of Heracles and border upon the Kynesians, who dwell furthest towards the sunset of all those who have their dwelling in Europe)." This confused passage was generally later interpreted as implying that the homeland of the Celts was at the source of the Danube not in Spain/France. However, this was mainly because of the association of the Hallstatt and La Tene cultures with the Celts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to [[Greek mythology]], Κελτός (''[[Celtus]]'') was the son of [[Heracles]] and Κελτίνη (''[[Keltine]]''), the daughter of Βρεττανός (''[[Bretannus]]'').<ref>Patrhenius, ''Love Stories 2, 30'' [http://www.theoi.com/Text/Parthenius2.html#30]</ref> Celtus became the [[eponymous]] ancestor of Celts.<ref>"<cite>Celtine, daughter of Bretannus, fell in love with Heracles 1 and hid away his kine (the cattle of Geryon) refusing to give them back to him unless he would first content her. From Celtus 1 the Celtic race derived their name.</cite>" {{cite web | title= (Ref.: Parth. 30.1-2)|url=http://homepage.mac.com/cparada/GML/Heracles1.html|accessdate=December 5|accessyear=2005 }}</ref> In Latin ''Celta'' came in turn from [[Herodotus]]' word for the [[Gauls]], ''Keltoi''. The Romans used ''Celtae'' to refer to continental Gauls, but apparently not to [[Insular Celtic languages|Insular Celts]]. The latter were long divided linguistically into [[Goidelic|Goidhels]] and [[Brythons]] (see Insular Celtic languages), although other research provides a more complex picture (see below under "Classification"). | ||

===The term in English=== | ===The term in English=== | ||

| − | The English word is modern, attested from | + | The English word is modern, attested from 1707 in the writings of [[Edward Lhuyd]] whose work, along with that of other late 17th century scholars, brought academic attention to the languages and history of these early inhabitants of Great Britain.<ref>(Lhuyd, p. 290) Lhuyd, E. ''"Archaeologia Britannica; An account of the languages, histories, and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain."'' (reprint ed.) Irish University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-7165-0031-0</ref> |

| − | In the [[18th century]] the interest in "[[primitivism]]" which led to the idea of the "[[noble savage]]" brought a wave of enthusiasm for all things "Celtic" | + | In the [[18th century]] the interest in "[[primitivism]]" which led to the idea of the "[[noble savage]]" brought a wave of enthusiasm for all things "Celtic." The antiquarian [[William Stukeley]] pictured a race of "Ancient Britons" putting up the "Temples of the Ancient Celts" such as [[Stonehenge]] before he decided in 1733 to recast the Celts in his book as [[Druid]]s. The [[Ossian]] fables written by [[James Macpherson]] and portrayed as ancient Scottish Gaelic language poems added to this romantic enthusiasm. The "Irish revival" came after the [[Catholic Emancipation]] Act of 1829 as a conscious attempt to demonstrate an Irish national identity, and with its counterpart in other countries subsequently became the "Celtic revival".<ref>*Lloyd and Jenifer Laing. ''Art of the Celts'', Thames and Hudson, London 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7</ref> |

| − | Nowadays "Celt" and "Celtic" are usually pronounced {{IPA|/kɛlt/}} and {{IPA|/kɛltɪk/}}, derived from a Greek root ''keltoi'', when referring to the ethnic group and its languages. | + | Nowadays "Celt" and "Celtic" are usually pronounced {{IPA|/kɛlt/}} and {{IPA|/kɛltɪk/}}, derived from a Greek root ''keltoi'', when referring to the [[ethnic group]] and its languages. The pronunciation {{IPA|/'sɛltɪk/}}, derived from the French ''celtique'', is mainly used for the names of sports teams (for example the [[National Basketball Association|NBA]] team, [[Boston Celtics]] and the [[Scottish Premier League|SPL]] side, [[Celtic F.C.]] in [[Glasgow]].<ref>"<cite>Although many dictionaries, including the OED, prefer the soft ''c'' pronunciation, most students of Celtic culture prefer the hard ''c''.</cite>" MacKillop, J. ''"Dictionary of Celtic Mythology."'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-869157-2</ref> |

===Modern uses=== | ===Modern uses=== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 56: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | In a modern context, the term "Celt" or "Celtic" can be used to denote areas where Celtic languages are spoken—this is the criterion employed by the [[Celtic League]] and the [[Celtic Congress]]. | + | In a modern context, the term "Celt" or "Celtic" can be used to denote areas where Celtic languages are spoken—this is the criterion employed by the [[Celtic League]] and the [[Celtic Congress]]. In this sense, there are six modern nations that can be defined as Celtic: Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales. Only four, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and Brittany have [[First language|native speakers]] of Celtic languages and in none of them is it the language of the majority. However, all six have significant traces of a Celtic language in personal and place names, and in culture and traditions. |

| + | |||

| + | Some people in [[Galicia (Spain)|Galicia]], [[Asturias]] and [[Cantabria]], in north-western [[Spain]], and [[Entre Douro e Minho|Minho]], [[Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro]] in [[Norte, Portugal|northern]] [[Portugal]] wish to be considered Celtic because of the strong Celtic [[cultural identity]] and acknowledgement of their Celtic past. The Celtic element is seen as the key differentiator of the [[Galician-Portuguese]] identity from the [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]] [[Iberians|Iberian]], [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] or [[Moors|Moorish]] influences of southern and eastern Spain, and southern Portugal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Regions of [[England]] such as [[Cumbria]] and [[Devon]] likewise retain some Celtic influences, yet haven't retained a Celtic language (even Cornwall became fully English-speaking during the 18th century) and are therefore not categorised as Celtic regions or nations. [[Cornish language|Cornish]] aside, the last attested Celtic language native to England was [[Cumbric language|Cumbric]], spoken in Cumbria and southern Scotland and which may have survived until the [[13th century]], but was most likely dead by the [[11th century|eleventh]]. As in the case of Cornish, there have been recent attempts to recreate it, based on medieval [[Mystery play|miracle plays]] and other surviving sources.{{Fact|date=March 2007}} | ||

| − | + | Another area of Europe associated with the Celts is [[France]], which traces its roots to the Gauls. In Scotland, the Gaelic language traces at least some of its roots to [[migration]] and settlement by the Irish [[Dál Riata]]/[[Scotti]]. The settlement of Germanic immigrants in the lowlands—among other things—reduced the spread of the Gaelic language which was supplanting Brythonic in Scotland; this has meant that Scots-Gaelic-speaking communities survive chiefly in the country's northern and western fringes. | |

===Use of the term for pre-Roman peoples of Britain and Ireland=== | ===Use of the term for pre-Roman peoples of Britain and Ireland=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[Dr Simon James (archaeologist)|Simon James]], formerly of the [[British Museum]], in his book ''The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention?'' makes the point that the [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] never used the term "Celtic" (or, rather, a cognate in [[Latin language|Latin]]) in reference to the peoples of | + | After its introduction by Edward Lluyd in 1707, the use of the word "Celtic" as an [[umbrella term]] for the pre-Roman peoples of Britain gained considerable popularity in the nineteenth century, and remains in common usage. However its historical basis is now seen as dubious by many historians and archaeologists, and this usage has been called into question. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Dr Simon James (archaeologist)|Simon James]], formerly of the [[British Museum]], in his book ''The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention?'' makes the point that the [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] never used the term "Celtic" (or, rather, a cognate in [[Latin language|Latin]]) in reference to the peoples of Britain and Ireland, and points out that the modern term "Celt" was coined as a useful umbrella term in the early 18th century to distinguish the non-English inhabitants of the [[archipelago]] when England united with Scotland in 1707 to create the [[Kingdom of Great Britain]] and the later union of [[Great Britain]] and Ireland as the [[United Kingdom]] in 1800. [[Nationalists]] in Scotland, Ireland and Wales looked for a way to differentiate themselves from England and assert their right to independence. James then argues that, despite the obvious linguistic connections, [[archaeology]] does not suggest a united Celtic culture and that the term is misleading, no more (or less) meaningful than "Western." | ||

[[Miranda Green]], author of ''Celtic Goddesses'', describes archaeologists as finding "a certain homogeneity" in the traditions in the area of Celtic habitation including Britain and Ireland — she sees the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland as having become thoroughly Celticized by the time of the Roman arrival, mainly through spread of culture rather than a movement of people. | [[Miranda Green]], author of ''Celtic Goddesses'', describes archaeologists as finding "a certain homogeneity" in the traditions in the area of Celtic habitation including Britain and Ireland — she sees the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland as having become thoroughly Celticized by the time of the Roman arrival, mainly through spread of culture rather than a movement of people. | ||

| − | In his book ''Iron Age Britain'', [[Barry Cunliffe]] concludes that "...there is no evidence in the British Isles to suggest that a population group of any size migrated from the continent in the first millennium BC..." | + | In his book ''Iron Age Britain'', [[Barry Cunliffe]] concludes that "...there is no evidence in the [[British Isles]] to suggest that a population group of any size migrated from the continent in the first millennium B.C.E....." Modern archaeological thought tends to disparage the idea of large population movements without facts to back them up, a caution which appears to be vindicated by some genetic studies. In other words, Celtic culture in the Atlantic Archipelago and continental Europe could have emerged through the peaceful convergence of local tribal cultures bound together by networks of [[trade]] and [[kinship]] — not by war and conquest. This type of peaceful [[convergence]] and [[cooperation]] is actually relatively common among tribal peoples; other well known examples of the phenomenon include the Six Nations of the [[Iroquois League]] and the [[Nuer]] of [[East Africa]]. He argues that the ancient Celts are thus best depicted as a loose and highly diverse collection of indigenous tribal societies bound together by trade, a common [[druidic]] religion, related languages, and similar political institutions — but each having its own local traditions. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Michael Morse]] in the conclusion of his book ''How the Celts came to Britain'' concedes that the concepts of a broad Celtic linguistic area and recognizably Celtic art have their uses, but argues that the term implies a greater unity than existed. Despite such problems he suggests that the term Celt is probably too deep-rooted to be replaced and — what is more important — it has the definition that we choose to give it. The problem is that the wider public reads into the term quite [[anachronistic]] concepts of [[Ethnocentrism|ethnic unity]] that no one on either side in the academic debate holds. | ||

| + | |||

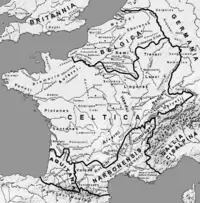

| + | ==Origins and geographical distribution== | ||

| + | [[Image:Celts 800-400BC.PNG|left|thumb|264px|The green area suggests a possible extent of (proto-)Celtic influence around 1000 B.C.E. The yellow area shows the region of birth of the [[La Tène culture|La Tène]] style. The orange area indicates an idea of the possible region of Celtic influence around 400 B.C.E.<!--note the date, don't change unless you know what you are doing: not greatest extent: ''Art of the Celts'' shows Iron Age finds at Culbin Sands and Deskford, Banff, in NE Scotland, and 'Dark Age' Celtic art further north—>]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Celts in Europe.png|200px|thumb|left|The Celts in Europe, past and present: <br/> | ||

| + | {{legend|#1a8000|present-day Celtic-speaking areas}} | ||

| + | {{legend|#27c600|other parts of the six most commonly recognized 'Celtic nations' and where a Celtic language is spoken but not the dominating language}} | ||

| + | {{legend|#97ffb6|other parts of Europe once peopled by Celts; modern-day inhabitants of many of these areas often claim a Celtic heritage and/or culture}}]] | ||

| + | ===Genetic Evidence=== | ||

| + | Most of our genes are inherited as a mixture of genetic material from both of our parents, but there are two exceptions. [[Mitochondrial DNA]] is passed down from our mothers unchanged and so can be traced back from daughter to mother. Similarly all boys inherit their [[Y chromosome]] from their father, since women do not have a Y chromosome, and so this can be traced back from son to father. [[Population genetics]] studies the patterns in the minor variations in this DNA to obtain information on the movement of populations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In his book ''Neanderthal'', archaeologist Douglas Palmer refers to genetic research conducted across Europe, then states the original modern genetic group in Europe arrived between 9,000 and [[3rd millennium B.C.E.|5,000 years ago]] with the spread of [[farming]], displacing the earlier [[hunter gatherer]] populations. Such displacement coincided with a population explosion, since farming is capable of supporting up to sixty times greater population than the hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the same area: | ||

| − | [[ | + | <blockquote>None of Europe's subsequent historic upheavals - even catastrophic wars and [[famine]]s - has seriously dented the old pattern set by the influx of farmers. The [[Goths]], [[Huns]] and Romans have come and gone without any significant impact on the ancient gene map of Europe.(Douglas Palmer)</blockquote> |

| − | + | However, modern genetic studies have shown that the original spread of modern man across Europe took place more than 20,000 years ago and re-expanded from refuges after the last Ice Age about 10,000 years ago. It now seems likely that the farmers from the Middle East did not generally displace the hunter-gatherers but that farming was slowly adopted by the latter. However, the association of the Indo-European language family with farming remains unproven. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Y-chromosomes]] of populations of the Atlantic Celtic countries have been found in several studies to belong primarily to [[haplogroup]] [[Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA)|R1b]], which implies that they are descendants of the first people to migrate into [[North-West Europe|north-western Europe]] after the last major [[ice age]]. According to the most recently published studies of European haplogroups, around half of the current male population of that portion of [[Eurasia]] is a descendant of the R1b haplogroup(subgroup of Central Asian haplogroup K). Haplotype R1b exceeds 90% of Y-chromosomes in parts of Wales, Ireland, Portugal and Spain.<ref>[http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~gallgaedhil/haplo_r1b_amh_13_29.htm]</ref><ref>[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MiamiCaptionURL&_method=retrieve&_udi=B6VRT-48PV5SH-12&_image=fig3&_ba=3&_coverDate=05%2F27%2F2003&_alid=339895807&_rdoc=1&_fmt=full&_orig=search&_cdi=6243&_qd=1&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=298af546d052683da43420d605615408]</ref><ref>[http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/21/7/1361/T03]</ref> | |

| − | + | Two published books - ''The Blood of the Isles'' by [[Bryan Sykes]] and ''The Origins of the British: a Genetic Detective Story'' by [[Stephen Oppenheimer]] - are based upon recent genetic studies, and show that the majority of Britons have ancestors from the [[Iberian Peninsula]], as a result of a series of migrations that took place during the [[Mesolithic]] and, to a lesser extent, the [[Neolithic]] eras.<ref>[http://www.breakingnews.ie/2004/09/09/story165780.html]</ref><ref>[http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1691416] </ref> | |

| − | + | Sykes says that the maternal and paternal origin of the British and Irish are different, with the former going back to Palaeolithic and Mesolithic times. He identifies close matches between the maternal clans of Iberia and those of the western half of the Isles. Once in the Isles the maternal lines mutated and diversified. He sees little genetic evidence relating to people from the heartland of the Hallstatt and La Tene cultures. On the paternal side he finds that the "Oisin" (R1b) clan is in the majority which has strong affinities to Iberia, with no evidence of a large scale arrival from Central Europe. He considers that the genetic structure of Britain and Ireland is "Celtic": | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>if by this we mean descent from people who were here before the Romans and who spoke a Celtic language.(Bryan Sykes)</blockquote> | |

| − | In Origins of the British (2006), Stephen Oppenheimer states (pages 375 and 378): | + | Oppenheimer's theory is that the modern day people of Wales, Ireland and Cornwall are mainly descended from Iberians who did not speak a Celtic language. In ''Origins of the British'' (2006), Stephen Oppenheimer states (pages 375 and 378): |

| − | <blockquote>By far the majority of male gene types in Britain and Ireland derive from [[Iberian Peninsula|Iberia]] (modern | + | <blockquote>By far the majority of male gene types in Britain and Ireland derive from [[Iberian Peninsula|Iberia]] (modern Spain and Portugal), ranging from a low of 59% in Fakenham, Norfolk to highs of 96% in Llangefni, north Wales and 93% Castlerea, Ireland. On average only 30% of gene types in England derive from north-west Europe. Even without dating the earlier waves of north-west European immigration, this invalidates the [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]] wipeout theory... |

| − | ...75-95% of Britain and Ireland (genetic) matches derive from Iberia...Ireland, coastal Wales, and central and west-coast Scotland are almost entirely made up from Iberian founders, while the rest of the non-English parts of Britain and Ireland have similarly high rates. England has rather lower rates of Iberian types with marked heterogeneity, but no English sample has less than 58% of Iberian samples...</blockquote> | + | ...75-95% of Britain and Ireland (genetic) matches derive from Iberia...Ireland, coastal Wales, and central and west-coast Scotland are almost entirely made up from Iberian founders, while the rest of the non-English parts of Britain and Ireland have similarly high rates. England has rather lower rates of Iberian types with marked heterogeneity, but no English sample has less than 58% of Iberian samples...(Stephen Oppenheimer)</blockquote> |

| − | == | + | ===Linguistic evidence=== |

| − | + | There are few written records of the ancient Celtic languages produced by the Celts themselves. Generally these are names on coins and stone inscriptions. Mostly the evidence is of personal names and place names in works by Greek and Roman authors. The date at which the proto-Celtic language split from Indo-European is disputed but may be as early as 6000 B.C.E., with it reaching Britain and Ireland by 3200 B.C.E., according to Forster and Toth. However, generally a later date is considered more likely by most scholars. Gray and Atkinson put the splitting off of Celtic languages at around 5000 B.C.E. In both cases there is a large estimating uncertainty. | |

| + | |||

| + | Several studies have been carried out of the Celtic place names of Europe. A recent one is that by Sims-Williams. The map of this data in Oppenheimer shows that the remaining placenames are mainly in Britain and northern France but extend from Iberia to the Danube. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A direct clue that the different names used by the Greek (who normally called any Celts ''Κελται'' or ''Γαλαται'') and the Latin authors (preferring ''Galli'') actually referred to speakers of the same or similar languages is given by the Christian author [[Jerome|Hieronymos]] (AD 342-419). In his commentary on [[Paul_of_Tarsus|St Paul's]] [[Epistle_to_the_Galatians|epistle to the Galatians]], he notes that the language of the Anatolian [[Galatia|Galatians]] in his day was still very similar to the language of the [[Treveri]].<ref>''Galatas excepto sermone Graeco, quo omnis oriens loquitur, propriam linguam eamdem pene habere quam Treviros'' ("That the Galatians, apart from the Greek language, which they speak just like the rest of the Orient, have their own language, which is almost the same as the Treverans'.") S. Eusebii Hieronymi commentariorum in epistolam ad Galatas libri tres, in ''Migne, Patrologia Latina'' 26, 382.</ref> St Jerome probably had first-hand knowledge of these Celtic languages, as he had both visited [[Trier|Augusta Treverorum]] and Galatia.<ref>Birkan, Kelten, p. 301.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Archaeological evidence=== | ||

| + | The only direct archaeological evidence for Celtic speaking peoples comes from coins and inscriptions. However it has been assumed that the Hallstatt (c. 1200-475 B.C.E.) and La Tene (c. 500-50 B.C.E.) cultures are associated with the Celts. Only in the final phase of La Tene are coins found. It has been suggested that the Hallstatt culture may have been adopted by speakers of different languages whereas the La Tene culture is more definitely associated with the Celts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Historical evidence=== | ||

| + | [[Polybius]] published a history of Rome about 150 B.C.E. in which he describes the Gauls of Italy and their conflict with Rome. [[Pausianias]] in the second century B.C.E. says that the Gauls "originally called Celts live on the remotest region of Europe on the coast of an enormous tidal sea." [[Posidonius]] described the southern Gauls about 100 B.C.E. Though his original work is lost it was used by later writers such as [[Strabo]]. The later, writing in the early first century AD, deals with Britain and Gaul as well as Spain, Italy and Galatia. [[Caesar]] wrote extensively about his [[Commentarii de Bello Gallico|Gallic Wars]] in 58-51 B.C.E. [[Diodorus Siculus]] wrote about the Celts of Gaul and Britain in his first century History. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Homeland=== | ||

| + | The question of the original homeland of the Celts has caused much controversy, with at least six competing theories. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1) The Celtic [[language family]] is a branch of the larger Indo-European family, which leads some scholars to a hypothesis that the original speakers of the Celtic [[proto-language]] may have arisen in the [[Black Sea|Pontic]]-[[Caspian Sea|Caspian]] [[steppes]] (see [[Kurgan]]). It is not generally accepted, however, that Celtic became differentiated from other branches of Indo-European at such an early stage. By the time speakers of Celtic languages enter history around 600 B.C.E., they were already split into several language groups, and spread over much of Central Europe, the [[Iberian peninsula]], Ireland and Britain. | ||

| − | + | 2) Some scholars think that the [[Urnfield|Urnfield culture]] of northern Germany and the Netherlands represents an origin for the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European family. This culture was preeminent in central [[Europe]] during the late [[Bronze Age]], from ca. 1200 B.C.E. until 700 B.C.E.., itself following the [[Unetice culture|Unetice]] and [[Tumulus cultures]]. The Urnfield period saw a dramatic increase in population in the region, probably due to innovations in technology and agricultural practices. The Greek historian [[Ephorus|Ephoros]] of Cyme in Asia Minor, writing in the fourth century B.C.E.., believed that the Celts came from the islands off the mouth of the [[Rhine]] who were "driven from their homes by the frequency of wars and the violent rising of the sea." | |

| − | + | The spread of [[Iron Age|iron-working]] led to the development of the [[Hallstatt culture]] directly from the Urnfield (c. 700 to 500 B.C.E.). [[Proto-Celtic]], the latest common ancestor of all known Celtic languages, is considered by this [[School (discipline)|school of thought]] to have been spoken at the time of the late Urnfield or early Hallstatt cultures, in the early [[first millennium B.C.E.]]. | |

| − | The spread of the Celtic languages to Ireland | + | The spread of the Celtic languages to Iberia, Ireland and Britain would have occurred during the first half of the [[1st millennium]], the earliest [[chariot burial]]s in Britain dating to ca. 500 B.C.E. Over the centuries they developed into the separate [[Celtiberian language|Celtiberian]], Goidelic and [[Brythonic languages]]. Whether Goidelic and Brythonic are descended from a common Insular-Celtic language, or reflect two separate waves of migration, is disputed. |

| − | The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the | + | 3) The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the La Tène culture of central Europe, and during the final stages of the [[Iron Age]] gradually transformed into the explicitly Celtic culture of early historical times. Celtic river-names are found in great numbers around the upper reaches of [[Danube|the Danube]] and Rhine, which led many Celtic scholars to place the [[ethnogenesis]] of the Celts in this area. Others however believe that the fact that the La Tène culture is too late to explain the original Celtic homeland; rather its extent demonstrates the subsequent spread of a pre-existing Celtic culture throughout [[Switzerland]], [[Austria]], southern and central [[Germany]], northern regions of [[Italy]], eastern France, [[Bohemia]], [[Moravia]], Portugal, [[Slovakia]] and parts of [[Hungary]] and [[Ukraine]]. The technologies, decorative practices and [[Metalworking|metal-working]] styles of the La Tène were certainly influential on the continental Celts, but they were highly derivative from the Greek, [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscan]] and [[Scythian]] decorative styles with whom the La Tène settlers frequently traded. |

| − | The technologies, decorative practices and metal-working styles of the La Tène were | ||

| − | + | 4) Today's Celtic nations are of course clustered along the Atlantic coast of Europe. Genetic studies now suggest (see [[Celt#Population Genetics|above]]) that certain Celtic-speaking peoples share genetic ancestry with the [[Basque people]] on the Atlantic coast of Spain and France.<ref>"In April last year, research for a BBC programme on the Vikings revealed strong genetic links between the Welsh and Irish Celts and the Basques of northern Spain and southern France. It suggested a possible link between the Celts and Basques, dating back tens of thousands of years." [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/2076470.stm English and Welsh are races apart]</ref> J. F. del Giorgio in ''[[The Oldest Europeans]]'' mentions that mythologists like [[Robert Graves]] reached a similar conclusion through [[comparative mythology]] and the study of Celtic customs. Celtic scholars however believe that such similarities reflect an earlier common heritage of the indigenous populations of the Atlantic fringe, long before the arrival of the Celts. | |

| − | + | 5) [[Diodorus Siculus]] and [[Strabo]] both suggest that the Celtic heartland was in southern France. The former says that the Gauls were to the north of the Celts but that the Romans referred to both as Gauls. Before the discoveries at Hallstatt and La Tene, it was generlly considered that the Celtic heartland was southern France, see Encyclopedia Brittannica for 1813. | |

| − | Pliny the Elder | + | 6) At odds with all the above theories is the assertion of [[Pliny the Elder]] that Celtica (the country of origin of the Celts) was in the delta of the river Guadalquivir in the south of Portugal and Spain: |

| − | "praeter haec in Celtica Acinippo, Arunda, Arunci, Turobriga, Lastigi, Salpesa, Saepone, Serippo. altera Baeturia, quam diximus Turdulorum et conventus Cordubensis, habet oppida non ignobilia Arsam, Mellariam, Mirobrigam Reginam, Sosintigi, Sisaponem" | + | "''praeter haec in Celtica Acinippo, Arunda, Arunci, Turobriga, Lastigi, Salpesa, Saepone, Serippo. altera Baeturia, quam diximus Turdulorum et conventus Cordubensis, habet oppida non ignobilia Arsam, Mellariam, Mirobrigam Reginam, Sosintigi, Sisaponem.''"<ref>[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Pliny_the_Elder/3*.html]</ref> This view is not shared by modern Celtic scholars, although the recent genetic research discussed above seem to support the Iberian origins of the peoples that were later called Celts. |

==Celts in Britain and Ireland== | ==Celts in Britain and Ireland== | ||

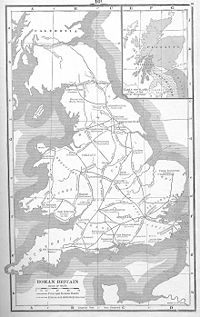

| − | The indigenous populations of Britain and Ireland today may be primarily descended from the ancient peoples that have long inhabited these lands, before the coming of Celtic and later Germanic peoples, language and culture. Little is known of their original culture and language, but remnants may remain in the names of some geographical features, such as the rivers [[River Clyde|Clyde]], [[Tamar]] and [[Thames]], whose etymology is unclear but almost certainly derive from a pre-Celtic [[Substratum|substrate]].{{Fact|date=February 2007}} By the Roman period, however, most of the inhabitants of the isles of | + | [[Image:Romanbritain.jpg|200px|thumb|Principal sites in Roman Britain, with indication of the Celtic tribes.]] |

| + | [[Image:CymruLlwythi.PNG|200px|thumb|Tribes of Wales at the time of the Roman invasion. Exact boundaries are conjectural.]] | ||

| + | The indigenous populations of Britain and Ireland today may be primarily descended from the ancient peoples that have long inhabited these lands, before the coming of Celtic and later Germanic peoples, language and culture. Little is known of their original culture and language, but remnants may remain in the names of some geographical features, such as the rivers [[River Clyde|Clyde]], [[River Tamar|Tamar]] and [[Thames]], whose etymology is unclear but almost certainly derive from a pre-Celtic [[Substratum|substrate]].{{Fact|date=February 2007}} By the Roman period, however, most of the inhabitants of the isles of Ireland and Britain were speaking [[Goidelic]] or [[Brythonic]] languages, close counterparts to Gallic languages spoken on the European mainland. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Historians explained this as the result of successive [[invasion]]s from the European continent by diverse Celtic-speaking peoples over the course of several centuries. The [[Book of Leinster]], written in the twelfth century, but drawing on a much earlier Irish oral tradition, states that the first Celts to arrive in Ireland were from Spain. In 1946 the Celtic scholar [[T. F. O'Rahilly]] published his extremely influential model of the [[early history of Ireland]] which postulated four separate waves of Celtic invaders. It is still not known what languages were spoken by the peoples of Ireland and Britain before the arrival of the Celts. |

| − | + | [[Image:Celtic dagger, scabbard and buckle.JPG|thumb|left|Celtic dagger found in Britain.]] | |

| − | + | Later research indicated that the culture had developed gradually and continuously.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} In Ireland little archaeological evidence was found for large intrusive groups of Celtic immigrants, suggesting to historians such as [[Colin Renfrew]] that the native late Bronze Age inhabitants gradually absorbed European Celtic influences and language. The very few continental La Tène culture style objects which had been found in Ireland could have been imports, the possessions of a few rich immigrants, or the result of selectively absorbing cultural influences from outside elites, further supporting this theory of cultural exchange rather than migration.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |

| − | + | [[Julius Caesar]] wrote of people in Britain who came from Belgium (the [[Belgae]]), but archaeological evidence which was interpreted in the 1930s as confirming this was contradicted by later interpretations.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} The archaeological evidence is of substantial cultural continuity through the first millennium B.C.E., although with a significant overlay of selectively-adopted elements of La Tène culture. There is numismatic and other evidence of continental-style states appearing in southern England close to the end of the period, possibly reflecting in part immigration by élites from various Gallic states such as those of the Belgae.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} However, this immigration would be far too late to account for the origins of Insular Celtic languages. In the 1970s the continuity model was taken to an extreme, popularised by [[Colin Burgess]] in his book ''[[The Age of Stonehenge]]'' which theorised that Celtic culture in Great Britain "emerged" rather than resulted from invasion and that the Celts were not invading aliens, but the descendants of the people of Stonehenge. The existence of Celtic language elsewhere in Europe, however, and the dating of the Proto-Celtic culture and language to the Bronze Age, makes the most extreme claims of continuity impossible. | |

| − | + | More recently a number of [[genetics|genetic]] studies have also supported this model of culture and language being absorbed by native populations. A study by Cristian Capelli, David Goldstein and others at [[University College, London|University College]], [[London]] showed that genes associated with Gaelic names in Ireland and Scotland are also common in certain parts of Wales and are similar to the genes of the Basque people, who speak a non-Indo-European language. This similarity supported earlier findings in suggesting a largely pre-Celtic genetic ancestry, possibly going back to the [[Paleolithic]]. They suggest that 'Celtic' culture and the Celtic language may have been imported to Britain by cultural contact, not mass invasions around 600 B.C.E.. A different possibility is that the Celtic language should differentiated from the Celtic culture. | |

| − | + | Some recent studies have suggested that, contrary to long-standing beliefs, the Germanic tribes ([[Angles]], [[Saxons]]) did not wipe out the [[Romano-British]] of England but rather, over the course of six centuries, conquered the native Brythonic people of what is now England and [[Gododdin|south-east Scotland]] and imposed their culture and language upon them, much as the Irish may have spread over the west of Scotland. Still others maintain that the picture is mixed and that in some places the indigenous population was indeed wiped out while in others it was assimilated. According to this school of thought the populations of Yorkshire, [[East Anglia]], Northumberland and the Orkney and [[Shetland Islands]] are those populations with the fewest traces of ancient (Celtic) British continuation.<ref>"<cite>By analyzing 1772 Y chromosomes from 25 predominantly small urban locations, we found that different parts of the British Isles have sharply different paternal histories; the degree of population replacement and genetic continuity shows systematic variation across the sampled areas.</cite>"{{PDFlink|[http://www.familytreedna.com/pdf/capelli2_CB.pdf A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles]|208 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 214000 bytes —>}}</ref> | |

==Celts in Gaul== | ==Celts in Gaul== | ||

| + | [[Image:Map Gallia Tribes Towns.png|thumb|200px|<center>Repartition of Gaul ca. 54 B.C.E.]] | ||

{{main|Gaul}} | {{main|Gaul}} | ||

| + | At the dawn of history in Europe, the Celts in present-day France were known as Gauls to the Romans. Gaul probably included Belgium and Switzerland. Their descendants were described by Julius Caesar in his ''[[Gallic Wars]]''. Eastern Gaul was the centre of the western La Tene culture. In later Iron Age Gaul the social organisation was similar to that of the Romans, with large towns. From the third century B.C.E. the Gauls adopted coinage and texts with Greek characters are known in southern Gaul from the second century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Greek traders founded Massalia in about 600B.C.E. with exchange up the Rhone valley. But trade was disrupted soon after 500B.C.E. and re-oriented over the Alps to the Po valley in Italy. The Romans arrived in the Rhone valley in the second century B.C.E. and found that a large part of Gaul was Celtic speaking. Rome needed land communications with its Spanish provinces and fought a major battle with the Saluvii at Entremont in 124-123 B.C.E. Gradually Roman control extended, the Roman Province of Gallia Transalpina being along the Mediterranean coast. The remainder was known as Gallia Comata "Hairy Gaul." | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 58 B.C.E. the Helvetii planned to migrate westward but were forced back by Julius Caesar. He then became incilved in fighting the various tribes in Gaul and by 55 B.C.E. most of Gaul had been overrun. In 52 B.C.E. Vercingetorix led a revolt gainst the Roman occupation but was defeated at the siege of Alesia and surrendered. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following the Gallic Wars of 58-51 B.C.E., Celticia formed the main part of Roman Gaul. Place name analysis shows that Celtic was used east of the Garonne river and south of the Seine-Marne. However, the Celtic language did not survive, being replaced by a Romance language, French. | ||

==Celts in Iberia== | ==Celts in Iberia== | ||

| − | {{ | + | [[Image:Prehispanic languages.gif|thumb|right|200px|Main [[language]] areas in [[Iberian Peninsula|Iberia]], showing Celtic and Proto-Celtic languages in green, and [[Iberian language]]s in purple, circa 250 B.C.E.]] |

| − | Traditional scholarship surrounding the Celts virtually ignored the [[Iberian Peninsula]], since material culture relatable to the [[Hallstatt]] and [[La Tène]] cultures that have defined Iron Age Celts was rare in Iberia, and did not provide a cultural scenario that could easily be linked to that of Central Europe. The Celts in Iberia | + | [[Image:ESPAÑAANTESDELAPRIMERAGUERRAPUNICAT.GIF|thumb|left|200px|Main language areas in Iberia circa 200 B.C.E. showing Celtic and Proto-Celtic languages in green.]] |

| + | {{See also|Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula|Prehistoric Iberia|Hispania|Lusitania|Gallaecia}} | ||

| + | Traditional [[18th century|18th]]/[[19th century|19th]] centuries scholarship surrounding the Celts virtually ignored the [[Iberian Peninsula]], since [[Archaeological culture|material culture]] relatable to the [[Hallstatt]] and [[La Tène]] cultures that have defined [[Iron Age]] Celts was rare in Iberia, and did not provide a cultural scenario that could easily be linked to that of Central Europe. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Modern scholarship, however, has proven that Celtic presence and influences were very substantial in Iberia. The Celts in Iberia were divided in two main archaeological and cultural groups, even if the divide is not very clear: | ||

| + | *One group, from [[Galicia (Spain)|Galicia]] and along the Iberian [[Atlantic Europe|Atlantic shores]]. They were made up of the [[Lusitanians]] (in [[Portugal]] and the Celtic region that [[Strabo]] called [[Celtica]] in the southwest including the [[Algarve]], inhabited by the [[Celtici]]), the [[Vettones]] and [[Vacceani]] peoples (of central west [[Spain]] and Portugal), and the [[Gallaecia]]n, [[Astures]] and [[Cantabri]]an peoples of the [[Castro culture]] of north and northwest Spain and Portugal). | ||

| + | *The [[Celtiberians|Celtiberian]] group of central Spain and the upper Ebro valley, which both present special, local features. The group originated when Celts migrated from what is now [[France]] and integrated with the local [[Iberians|Iberian people]]. | ||

| − | + | The origins of the Celtiberians might provide a key to unlocking the Celticization process in the rest of the Peninsula. The process of celticization of the SW by the Keltoi and NW is however not a simple celtiberian question. Recent investigation about the [[Callaici]] [[Bracari]] in NW Portugal is bringing new approaches to understand celtic culture evidences (language, art and religion) in western Iberia.<ref>[http://arkeotavira.com/Mapas/Iberia/Populi.htm Archeological site of Tavira], official website</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Celts in Italy== | |

| + | There was an early Celtic presence in northern Italy since inscriptions dated to the sixth century B.C.E. have been found there. In 391B.C.E.. Celts "who had their homes beyond the Alps streamed through the passes in great strength and seized the territory that lay between the Appeninne mountains and the Alps" according to [[Diodorus Siculus]]. The [[River Po|Po Valley]] and the rest of northern Italy (known to the Romans as [[Cisalpine Gaul]]) was inhabited by Celtic-speakers who founded cities such as [[Milan]]. Later the Roman army was routed at the battle of Allia and Rome was sacked in 390B.C.E.. | ||

| − | + | At the battle of Telemon in 225 B.C.E. a large Celtic army was trapped between two Roman forces and crushed. | |

| − | + | The defeat of the combined [[Samnium|Samnite]], Celtic and Etruscan alliance by the Romans in the [[Samnite Wars|Third Samnite War]] sounded the beginning of the end of the Celtic domination in mainland Europe, but it was not until 192 B.C.E. that the Roman armies conquered the last remaining independent Celtic kingdoms in Italy. | |

| − | The | + | The Celts settled much further south of the Po River than many maps show. Remnants in the town of Doccia, in the province of [[Emilia-Romagna]], showcase Celtic houses in very good condition dating from about the 4th century B.C.E.. |

| − | == | + | ==Celts in other regions== |

| − | The | + | The Celts also expanded down the [[Danube]] river and its tributaries. On of the most influential tribes, the [[Scordisci]], had established their capital at [[Singidunum]] in 3rd century B.C.E., which is present-day [[Belgrade]]. The concentration of hill-forts and cemeteries shows a density of population in the [[Tisza]] valley of modern-day [[Vojvodina]], [[Hungary]] and into [[Ukraine]]. Expansion into [[Romania]] was however blocked by the [[Dacians]]. |

| − | + | Further south, Celts settled in [[Thrace]] ([[Bulgaria]]), which they ruled for over a century, and [[Anatolia]], where they settled as the [[Galatia]]ns. Despite their geographical isolation from the rest of the Celtic world, the Galatians maintained their Celtic language for at least seven hundred years. [[St Jerome]], who visited Ancyra (modern-day [[Ankara]] in 373C.E., likened their language to that of the [[Treveri]] of northern Gaul. | |

| + | |||

| + | The [[Boii]] tribe gave their name to [[Bohemia]] ([[Czech Republic]]) and Celtic artefacts and cemeteries have been discovered further east in both [[Poland]] and [[Slovakia]]. A celtic coin ([[Biatec]]) from [[Bratislava]]'s mint is displayed on today's Slovak 5 crown coin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As there is no archaeological evidence for large scale invasions in some of the other areas, one current school of thought holds that Celtic language and culture spread to those areas by contact rather than invasion. However, the Celtic invasions of Italy, Greece, and western Anatolia are well documented in Greek and Latin history. Examine the Map of Celtic Lands for more information.<ref>{{cite web | title= Map of Celtic Lands | url=http://www.resourcesforhistory.com/map.htm | accessdate=December 5 | accessyear=2005 }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are records of Celtic mercenaries in Egypt serving the Ptolomies. Thousands were employed in 283-246 B.C.E. and they were also in service around 186 B.C.E. They attempted to overthrow Ptolomy II. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Romanisation== | ||

| + | Under Caesar the Romans conquered Celtic Gaul, and from [[Claudius]] onward the Roman empire absorbed parts of Britain. Roman local government of these regions closely mirrored pre-Roman '[[tribe|tribal]]' boundaries, and archaeological finds suggest native involvement in local government. [[Latin]] was the [[official language]] of these regions after the conquests. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The native peoples under Roman rule became Romanized and keen to adopt Roman ways. Celtic art had already incorporated classical influences, and surviving Gallo-Roman pieces interpret classical subjects or keep faith with old traditions despite a Roman overlay. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Roman occupation of Gaul, and to a lesser extent of Britain, led to Roman-Celtic [[syncretism]] (see [[Roman Gaul]], [[Roman Britain]]). In the case of Gaul, this eventually resulted in a [[language shift]] from [[Gaulish language|Gaulish]] to [[Vulgar Latin]] (see also [[Gallo-Roman culture]]). However, the Celts were master horsemen,{{Fact|date=May 2007}} which so impressed the Romans{{Fact|date=May 2007}} that they adopted [[Epona]], the Celtic horse goddess, into their pantheon. During and after the fall of the Roman Empire many parts of France threw out their Roman administrators. | ||

[[Image:Ccross.svg|thumb|right|170px|A [[Celtic cross]].]] | [[Image:Ccross.svg|thumb|right|170px|A [[Celtic cross]].]] | ||

| − | + | == Celtic social system and arts == | |

| − | + | To the extent that sources are available, they depict a pre-Christian Celtic [[social structure]] based formally on class and kinship. Patron-client relationships similar to those of Roman society are also described by Caesar and others in the Gaul of the [[1st century B.C.E.|first century B.C.E.]]. | |

| + | |||

| + | In the main, the evidence is of tribes being led by kings, although some argue that there is evidence of oligarchical republican [[Form of government|forms of government]] eventually emerging in areas in close contact with Rome. Most descriptions of Celtic societies describe them as being divided into three groups: a warrior aristocracy; an intellectual class including professions such as druid, poet, and jurist; and everyone else. There are instances recorded where women participated both in warfare and in kingship, although they were in the minority in these areas. In historical times, the offices of high and low kings in Ireland and Scotland were filled by election under the system of [[tanistry]], which eventually came into conflict with the feudal principle of [[primogeniture]] where the succession goes to the first born son. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Archaeological discoveries at [http://www.unc.edu/celtic/catalogue/femdruids/Vix.html the Vix Burial] indicate that women could achieve high status and power within at least one Celtic society. As Celtic history was only carried forward by [[oral tradition]], it has been advanced that the traditions finally recorded in the [[7th century|seventh century]] can be projected back through Celtic history.<ref>{{cite book | publisher= Academy Press | date=January 1981 | author= Donnchadh O Corrain |title =Celtic Ireland}}</ref> If this is so then, according to the [[Cáin Lánamna]], a woman had the right to demand divorce, take back whatever property she brought into the marriage and be free to remarry. If later Celtic tradition can be projected back, and from Ireland to Britain and the continent, then Celtic law demanded that children, the elderly, and the [[Developmental disability|mentally handicapped]] be looked after. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Little is known of family structure among the Celts. [[Athenaeus]] in his ''Deipnosophists,'' 13.603, claims that "the Celts, in spite of the fact that their women are the most beautiful of all the barbarian tribes, prefer boys as sexual partners. There are some of them who will regularly go to bed – on those animal skins of theirs – with a pair of lovers," implying a woman and a boy. Such reports reflect an outsiders observation of Celtic culture.<ref> Athenaeus ''The Deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the Learned of Athenaeus'', Book XIII, pp. 961. [http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/Literature/Literature-idx?type=turn&entity=Literature.AthV3.p0149&q1=celt&pview=hide The Literature Collection, University of Wisconsin Digital Collections,].</ref> It is unknown whether Athenaeus, born in Egypt of Greek origin ever visited any Celts since little is known about him beyond his surviving writings. | ||

| − | + | Patterns of settlement varied from decentralised to the urban. The popular stereotype of non-urbanised societies settled in [[hillfort]]s and [[dun]]s, drawn from Britain and Ireland contrasts with the urban settlements present in the core Hallstatt and La Tene areas, with the many significant oppida of Gaul late in the first millennium B.C.E., and with the towns of [[Cisalpine Gaul|Gallia Cisalpina]]. | |

| − | + | There is archaeological evidence to suggest that the pre-Roman Celtic societies were linked to the network of overland [[trade route]]s that spanned Eurasia. Large prehistoric trackways crossing bogs in Ireland and Germany have been found by archaeologists. They are believed to have been created for wheeled transport as part of an extensive roadway system that facilitated trade.<ref>{{cite journal | title=Neolithic wooden trackways and bog hydrology |journal= Journal of Paleolimnology |publisher =Springer Netherlands | volume =12 | date= January, 1994 | Pages= 49-64}}</ref> The territory held by the Celts contained tin, lead, iron, silver and gold.<ref> {{PDFlink|http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-ar_r_wal.pdf|369 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 377990 bytes —>}} Beatrice Cauuet (Université Toulouse Le Mirail, UTAH, France)</ref> Celtic smiths and metalworkers created weapons and jewelry for international trade, particularly with the Romans. Celtic traders were also in contact with the Phoenicians: gold works made in pre-Roman Ireland have been unearthed in archaeological digs in Palestine and trade routes between Atlantic societies and Palestine dating back to at least [[1600s B.C.E..|1600 B.C.E.]]. | |

| − | + | Local trade was largely in the form of barter, but as with most tribal societies they probably had a reciprocal economy in which goods and other services are not exchanged, but are given on the basis of mutual relationships and the obligations of kinship. Low value coinages of potin, silver and bronze, suitable for use in trade, were minted in most Celtic areas of the continent, and in South-East Britain prior to the Roman conquest of these areas. | |

| − | + | There are only very limited records from pre-Christian times written in Celtic languages. These are mostly inscriptions in the Roman, and sometimes Greek, alphabets. The [[Ogham]] script was mostly used in early Christian times in Ireland and Scotland (but also in Wales and England), and was only used for ceremonial purposes such as inscriptions on gravestones. The available evidence is of a strong oral tradition, such as that preserved by bards in Ireland, and eventually recorded by monasteries. The oldest recorded rhyming poetry in the world is of Irish origin and is a transcription of a much older [[Epic poetry|epic poem]], leading some scholars to claim that the Celts invented [[Rhyme]]. They were highly skilled in visual arts and Celtic art produced a great deal of intricate and beautiful metalwork, examples of which have been preserved by their distinctive burial rites. | |

| − | + | In some regards the Atlantic Celts were conservative, for example they still used [[chariot]]s in combat long after they had been reduced to ceremonial roles by the Greeks and Romans, though when faced with the Romans in Britain, their [[chariot tactics]] defeated the invasion attempted by Julius Caesar. | |

| − | == Celtic | + | == The Celtic Calendar == |

| − | + | ||

| + | The [[Coligny Calendar]], which was found in 1897 in [[Coligny, Ain|Coligny]], [[Ain]], was engraved on a [[bronze]] tablet, preserved in 73 fragments, that originally was 1.48 m wide and 0.9 m high (Lambert p.111). Based on the style of lettering and the accompanying objects, it probably dates to the end of the [[2nd century]].<ref>Lambert, Pierre-Yves (2003). ''La langue gauloise''. Paris, Editions Errance. 2nd edition. ISBN 2-87772-224-4. Chapter 9 is titled "Un calandrier gaulois"</ref> It is written in Latin inscriptional capitals, and is in the [[Gaulish language]]. The restored tablet contains sixteen vertical columns, with sixty-two months distributed over five years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The French archaeologist J. Monard speculated that it was recorded by [[druid]]s wishing to preserve their tradition of timekeeping in a time when the [[Julian calendar]] was imposed throughout the [[Roman Empire]]. However, the general form of the calendar suggests the public peg calendars (or ''parapegmata'') found throughout the Greek and Roman world <ref> Lehoux, D. R. ''Parapegmata: or Astrology, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World'', pp63-5. [http://www.collectionscanada.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/ftp03/NQ53766.pdf PhD Dissertation, University of Toronto, 2000].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | There were four major festivals in the Celtic Calendar: "Imbolc" on the 1st of February, possibly linked to the lactation of the ewes and sacred to the Irish Goddess Brigid. "Beltain" on the 1st of May, connected to fertility and warmth, possibly linked to the Sun God Belenos. "Lughnasa" on the 1st of August, connected with the harvest and associated with the God Lugh. And finally "Samhain" on the 1st of November, possibly the start of the year.<ref>James, Simon (1993). "Exploring the World of the Celts" Reprint, 2002. pp-155.</ref> Two of these festivals, Beltain and Lugnasa are shown on the Coligny Calendar by sigils, and it is not too much of a stretch of the imagination to match the first month on the Calendar (Samonios) to Samhain. Lughnasa does not seem to be shown at all however.<ref>The Coligny Calendar, Roman Britain, 2/10/01: [http://www.roman-britain.org/coligny.htm]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Celtic Calendar seems to be based on astronomy<ref>Celtic Astrology [http://www.livingmyths.com/Celticyear.htm]</ref> but how any astrology system would have worked is harder to tell. We have to base our knowledge on [[Old Irish]] manuscripts, none of which have been published or fully translated. It seems to have been based on an indigenous Irish symbol system, and not that of any of the more commonly-known astrological systems such as [[Western astrology|Western]], [[Chinese astrology|Chinese]] or [[Jyotisha|Vedic]] astrology.<ref>{{cite journal| first =Peter Berresford | last =Ellis | authorlink = | coauthors = | title=Early Irish Astrology: An Historical Argument|journal=Réalta|volume=vol.3|issue=issn.3|year=1996 | url =http://www.radical-astrology.com/irish/miscellany/ellis.html|}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Celtic women == | ||

| + | === Sexual norms === | ||

| + | There are instances recorded where women participated both in warfare and in kingship, although they were in the minority in these areas. [[Plutarch]] reports Celtic women acting as ambassadors to avoid a war amongst Celts chiefdoms on the Po valley during the fourth century B.C.E.<ref name=Ellis> | ||

| + | {{cite book | ||

| + | |author=Ellis, Peter Berresford | ||

| + | |title= ''The Celts: A History'' | ||

| + | |pages= pp.49-50 | ||

| + | |publisher=Caroll & Graf | ||

| + | |date= 1998 | ||

| + | |id= ISBN 0-786-71211-2}} | ||

| + | </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Sexual norm|sexual freedom]] of Celtic women was noted by [[Cassius Dio]]:<ref name= "Dio Cassius"> Roman History Volume IX Books 71-80, Dio Cassiuss and Earnest Carry translator (1927), Loeb Classical Library ISBN-10: 0674991966.</ref> | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>...a very witty remark is reported to have been made by the wife of Argentocoxus, a Caledonian, to [[Livia|Julia Augusta]]. When the empress was jesting with her, after the treaty, about the free intercourse of her sex with men in Britain, she replied: "We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest." Such was the retort of the British woman. (Cassius Dio)</blockquote> | |

| − | + | === Celtic women as warriors === | |

| + | Despite the fact that Celtic Princesses and the [[badb]] were cross-dressing symbols of sex and politics, rather than historical representations of real fighting women, [[Posidonius]] and [[Strabo]] described an island of women, where men could not venture for fear of death, and women ripped each other apart.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| + | |author=Bitel, Lisa M. | ||

| + | |title= Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland | ||

| + | |publisher= Cornell University Press | ||

| + | |year= 1996| | ||

| + | pages= p.212| | ||

| + | id=ISBN 0-801-48544-4}}</ref> Other writers such as [[Ammianus Marcellinus]], [[Tacitus]] mentioned Celtic women inciting, participating, and leading battles.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| + | |author=Tierney, J. J. | ||

| + | |title=The Celtic Ethnography of Posidonius, PRIA 60 C | ||

| + | |year=1960 | ||

| + | |publisher=Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy | ||

| + | |pages=pp1.89-275 | ||

| + | }}</ref> Poseidonius anthropological comments on the Celts had common themes, primarily primitivism, extreme ferocity, cruel sacrificial practices, and the strength and courage of their women.<ref> | ||

| + | {{cite book | ||

| + | |title = Celts and the Classical World | ||

| + | |author = Rankin, David | ||

| + | |publisher= Routledge | ||

| + | |year=1996 | ||

| + | |pages=p.80 | ||

| + | |id=ISBN 0-415-15090-6 | ||

| + | }}</ref> Contemporary historians ascribe this to the Romans and Greeks want for a upside-down world for the ''barbarians'', who both frightened and fascinated them. It is interesting to note that the Celtic God of Martial Arts was, in all fact, a woman. | ||

| − | + | ==== Notable Celtic women ==== | |

| + | * [[Cartimandua]], (or ''Cartismandua'', ruled ca.43 B.C.E. - 69 B.C.E.), was a queen of the [[Brigantes]], a [[List of Celtic tribes|British Celtic tribe]] who lived between the rivers [[Tyne]] and [[Humber]], that formed a large tribal agglomeration in northern England. She was the only queen in early [[Roman Britain]], identified as ''regina'' by [[Tacitus]]. | ||

| − | + | * [[Camma (Celt priestess|Camma]], priestess of [[Brigandu]], wife of [[Sinatos]]. | |

| − | + | * [[Boudica]], (also spelled ''Boudicca''), and often referred to as Boadicea, outside academic circles, (d. [[60 B.C.E.|60/61 B.C.E..]]) was a [[Queen regnant|queen]] of the [[Brythonic]] Celtic [[Iceni]] people of [[Norfolk]] in Eastern [[Roman Britain|Britain]] who led a major but ultimately failed uprising of the tribes against the occupying forces of the [[Roman Empire]]. ''(See [[Battle of Watling Street]])'' | |

| − | + | * [[Chiomaca]], wife of [[Ortagion]], chief of the [[Tolistoboii]] of [[Galatia]] (189 B.C.E.). | |

| − | + | * [[Queen Teuta]], (also ''Queen Tefta''), was an [[Illyria]]n queen and regent who reigned approximately from 231 B.C.E. to 228 B.C.E.. | |

| − | + | * [[Macha Mong Ruad]], daughter of [[Áed Ruad]]. After the death of her husband [[Cimbáeth]], and defeating all claimants to the throne, she became the [[List of High Kings of Ireland|High Queen]] in 337 B.C.E.<ref>{{cite book | |

| + | |author=Ellis, Peter Berresford | ||

| + | |title= ''The Celts: A History'' | ||

| + | |pages= pp.89-90 | ||

| + | |publisher=Caroll & Graf | ||

| + | |date= 1998 | ||

| + | |id= ISBN 0-786-71211-2}}</ref> | ||

| − | + | * [[Medb of Connacht]]. | |

| − | + | * [[Elen Luyddog]], (widely known as ''Helen of the Hosts'' or ''Elen'') was a Romano-British princess and the wife of [[Magnus Clemens Maximus]], Emperor in Britain, Gaul and Spain, where he died seeking imperial recognition in 388 C.E. She is also considered a founder of churches in Wales and remembered as a saint. | |

| − | + | * [[Scáthach]] (''Shadowy''), a legendary [[Scotland|Scottish]] [[warrior]] woman and [[martial arts]] teacher who trained the legendary [[Ulster]] hero [[Cúchulainn]] in the arts of combat. Texts describe her homeland as "Alpi," which commentators associate with ''[[Alba]]'', the Gaelic name of Scotland, and associated with the [[Isle of Skye]], where her residence ''Dún Scáith'' (Fort of Shadows) stands. | |

| − | ==Celtic | + | ==Celtic Men== |

| − | + | [[Image:Dying gaul.jpg|300px|thumb|300px|The ''Dying Gaul'', a Roman marble copy of a [[Hellenistic]] work of the late third century B.C.E. [[Capitoline Museums]], Rome]] | |

| + | According to Didorus Siculus : | ||

| + | <blockquote>The Gauls are tall of body with rippling muscles and white of skin and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so for they also make it their practice by artificial means to increase the distinguishing colour which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater and they pull it back from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance is like that of Satyrs and Pans since the treatment of their hair makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs in no respect from the mane of horses. Some of them shave the beard but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks but they let the moustache grow until it covers the mouth. (Diodorus Siculus)</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | During the later Iron Age the Gauls generally wore long-sleeved shirts of tunics and long trousers. Clothes were made of wool or linen, with some silk being used by the rich. Cloaks were worn in winter. Broaches and armlets were used but the most famous item of jewellery was the torc. | |

| − | + | ===Homosexuality=== | |

| + | Athenaeus says that : | ||

| + | <blockquote>The Celts, though they have very beautiful women, enjoy ''young'' boys more: so that some of them often have two lovers to sleep with on their beds of animal skins. This is widely debated among modern historians as historic fact. It is often claimed that Athenaesus may have misunderstood certain Celtic traditions and related them to the Greco-Roman culture more familiar to him.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ===Notable Celtic Men=== | |

| + | * [[Bolgios]] Leader of the Galatii in Macedonia. | ||

| + | * [[Brennus]] Leader of the Celts who sacked Rome. | ||

| + | * [[Cassivellaunus]] Leader of Britons against Julius Caesar. | ||

| + | * [[Commius]] Leader of the Belgae who settled in Britain. | ||

| + | * [[Cunobelinus]] Leader of the Catuvellauni against Claudius. | ||

| + | * [[Vercingetorix]] Led revolt in Gaul against Julius Caesar. | ||

| + | * [[Verica]] Leader of the Atrebates whose flight to Rome was the pretext for the invasion of Britain. | ||

| − | + | == Celtic warfare and weapons == | |

| + | {{sect-stub}} | ||

| + | [[Image:CináedmacAilpín.JPG|thumb|Cináed mac Ailpín, king of the [[Picts]]]] | ||

| + | [[Endemic warfare|Tribal warfare]] appears to have been a regular feature of Celtic societies. While epic literature depicts this as more of a sport focused on raids and hunting rather than organised territorial conquest, the historical record is more of tribes using warfare to exert political control and harass rivals, for economic advantage, and in some instances to conquer territory. | ||

| − | [[ | + | The Celts were described by classical writers such as [[Strabo]], [[Livy]], [[Pausanias]], and [[Florus]] as fighting like "wild beasts," and as [[hordes]]. [[Dionysius of Halicarnassus|Dionysius]] said that their "manner of fighting, being in large measure that of wild beasts and frenzied, was an erratic procedure, quite lacking in [[military science]]. Thus, at one moment they would raise their swords aloft and smite after the manner of [[Boar|wild boars]], throwing the whole weight of their bodies into the blow like hewers of wood or men digging with mattocks, and again they would deliver crosswise blows aimed at no target, as if they intended to cut to pieces the entire bodies of their adversaries, protective armour and all".<ref>Dionysius of Halicarnassus, ''Roman Antiquities'' |

| + | p259 Excerpts from Book XIV</ref> Such descriptions have been challenged by contemporary historians.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| + | |author=Ellis, Peter Berresford | ||

| + | |title= ''The Celts: A History'' | ||

| + | |pages= pp.60-3 | ||

| + | |publisher=Caroll & Graf | ||

| + | |date= 1998 | ||

| + | |id= ISBN 0-786-71211-2}}</ref> | ||

| − | == The Celts as head-hunters == | + | === The Celts as head-hunters === |

"Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world." —[[Paul Jacobsthal]], ''Early Celtic Art''. | "Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world." —[[Paul Jacobsthal]], ''Early Celtic Art''. | ||

| − | The Celtic cult of the severed head is documented not only in the many sculptured representations of severed heads in | + | The Celtic cult of the severed head is documented not only in the many sculptured representations of severed heads in La Tène carvings, but in the surviving Celtic mythology, which is full of stories of the severed heads of heroes and the saints who carry their decapitated heads, right down to ''Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'', where the [[Green Knight]] picks up his own severed head after Gawain has struck it off, just as [[St. Denis]] carried his head to the top of [[Montmartre]]. Separated from the mundane body, although still alive, the animated head acquires the ability to see into the mythic realm. |

A further example of this regeneration after beheading lies in the tales of [[Connemara]]'s [[St. Feichin]], who after being beheaded by Viking pirates carried his head to the Holy Well on [[Omey Island]] and on dipping the head into the well placed it back upon his neck and was restored to full health. | A further example of this regeneration after beheading lies in the tales of [[Connemara]]'s [[St. Feichin]], who after being beheaded by Viking pirates carried his head to the Holy Well on [[Omey Island]] and on dipping the head into the well placed it back upon his neck and was restored to full health. | ||

[[Diodorus Siculus]], in his 1st century ''History'' had this to say about Celtic head-hunting: | [[Diodorus Siculus]], in his 1st century ''History'' had this to say about Celtic head-hunting: | ||

| − | :"They cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle and attach them to the necks of their horses. The blood-stained spoils they hand over to their attendants and carry off as booty, while striking up a paean and singing a song of victory; and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses, just as do those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting. They embalm in cedar oil the heads of the most distinguished enemies, and preserve them carefully in a chest, and display them with pride to strangers, saying that for this head one of their ancestors, or his father, or the man himself, refused the offer of a large sum of money. They say that some of them boast that they refused the weight of the head in gold." | + | :"They cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle and attach them to the necks of their horses. The blood-stained spoils they hand over to their attendants and carry off as booty, while striking up a paean and singing a song of victory; and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses, just as do those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting. They embalm in [[cedar oil]] the heads of the most distinguished enemies, and preserve them carefully in a chest, and display them with pride to strangers, saying that for this head one of their ancestors, or his father, or the man himself, refused the offer of a large sum of money. They say that some of them boast that they refused the weight of the head in gold." |

| + | |||

| + | The Celts believed that if they attached the head of their enemy to a pole or a fence near their house, the head would start crying when the enemy was near. If the head was taken from an enemy who was important enough, they would put it in a church and pray to it believing it had magic powers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Celtic headhunters venerated the image of the severed head as a continuing source of spiritual power. If the head is the seat of the soul, possessing the severed head of an enemy, honorably reaped in battle, added prestige to any warrior's reputation. According to tradition the buried head of a god or hero named [[Bran the Blessed]] protected Britain from invasion across the [[English Channel]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Celtic Gods== | ||

| + | Many Celtic gods are known from texts and inscriptions from the Roman period, such as Aquae Sulis, while others have been inferred from place names such as Lugdunum "stronghold of Lug." Rites and sacrifices were carried out by priests, some known as Druids. The Celts did not see their gods as having a human shape until late in the Iron Age. Shrines were situated in remote areas such as hilltops, groves and lakesCeltic religious patterns. | ||

| + | {{main|Celtic polytheism}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Celtic religious patterns were regionally variable, however some patterns of deity forms, and ways of worshiping these deities, appear over a wide geographical and temporal range. The Celts worshipped both gods and goddesses. In general, the gods were deities of particular skills, such as the many-skilled [[Lugh]] and [[Dagda]], and the goddesses associated with natural features, most particularly rivers, such as [[Boann]], goddess of the [[River Boyne]]. This was not universal, however, as Goddesses such as [[Brighid]] and [[Morrígan|The Morrígan]] were associated with both natural features ([[clootie well|holy wells]] and the River Unius) and skills such as blacksmithing, healing and warfare.<ref name="Sjoestedt">Sjoestedt, Marie-Louise (1982) ''Gods and Heroes of the Celts''. Translated by Myles Dillon, Berkeley, CA, Turtle Island Foundation ISBN 0-913666-52-1, pp. 24-46.</ref> | ||

| + | |||