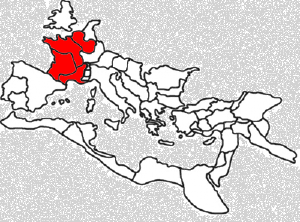

Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul consisted of an area of provincial rule in the Roman Empire, in modern day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and western Germany. Roman control of the area lasted for 600 years. The Roman Empire began its takeover of what was Celtic Gaul in 121 B.C.E., when it conquered and annexed the southern reaches of the area. Julius Caesar completed the task by defeating the Celtic tribes in the Gallic Wars of 58-51 B.C.E. and the Romanization was quick and large; Latin was spoken by a majority of Gauls in the first century C.E. but with some remains of the Gallic language. Following the Romans' defeat by the Franks at the Battle of Soissons in 486 C.E., Gaul came under the rule of the Merovingians, the first kings of France. The only attempt at a rebellion against Rome was an unsuccessful uprising in 257 C.E. under Postumus.

Gaul was not only closer to the imperial center than Roman Britain but served as an important buffer between Rome and the area then known as Germania, where fighting was constant on the borders of the Roman province. Culturally, France absorbed Roman civilization to a greater degree than either Britain or Germany. After the collapse of the Western half of the Roman Empire, it would be French rulers who played a vital role in maintaining consciousness of supra-national, European identity of which the Holy Roman Empire was an early manifestation. In the modern era, France has strongly supported the development of the European Union as a supra-national entity ensuring economic prosperity, the rule of law, peace and respect for human rights for all European citizens. The legacy of Roman Gaul lies behind this willingness to identify French interests with the interests of other people within a common geographical region. Extended to the world of nations, such a vision would become a foundation on which a more cooperative and equitable world could be built.

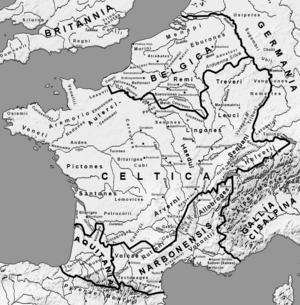

Geographical divisions

- Gallia Narbonensis, formerly Gallia Transalpina or "Gaul across the Alps" was originally conquered and annexed in 121 B.C.E. in an attempt to solidify communications between Rome and the Iberian peninsula. It comprised the present-day region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, most of Languedoc-Roussillon, and roughly the southeastern half of Rhône-Alpes.

- Gallia Comata. or "long haired Gaul." Comata encompassed the remainder of present-day France, Belgium, and westernmost Germany, which the Romans gained through the victory over the Celts in the Gallic Wars. The Romans divided Gallia Comata into three provinces:

- Gallia Aquitania

- Gallia Belgica

- Gallia Lugdunensis

The Romans gave these divisions the term pagi (Pagus was the Latin name for a small territorial subdivision, from which later comes the French word pays, meaning both "region" and "country"); these pagi were organized into civitates (provinces). These administrative groupings would be taken over by the Romans in their system of local control, and these civitates would also be the basis of France's eventual division into bishoprics and dioceses, which would remain in place—with slight changes—until the French Revolution. Roman Gaul was administered from Lyon.

Language and Culture

The Gaulish language and cultural identity would—in the five centuries between Caesar's conquest and the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 C.E., when the barbarian Odoacer overthrew the emperor Romulus Augustulus—undergo a process of syncretism, and evolve into a hybrid Gallo-Roman culture. Current historical research believes that Roman Gaul was "Roman" only in certain (albeit major) social contexts (the importance of which hindered a better historical understanding of the permanence of many Celtic elements). The Roman influence was most apparent in the following areas:

- The Druidic religion which existed in the area was ordered suppressed by Emperor Claudius I, and in later centuries Christianity was introduced. The prohibition of Druids and the syncretic nature of the Roman religion led to disappearance of the Celtic religion (which remains to this day poorly understood: current knowledge of the Celtic religion is based on archeology and via literary sources from several isolated areas such as Ireland and Wales).

- The Romans easily imposed their administrative, legal, economic, roadbuilding, infrastructure, artistic (especially in terms of monumental art and architecture) and literary culture, all the moreso given that there was little in the pre-existing Celtic culture to compete with these areas.

After the Roman conquest of Gaul (completed in 51 B.C.E.), "Romanization" of the Celtic upper classes proceeded more rapidly than the "Romanization" of the lower classes. These classes may have spoken a Latin language mixed with Gallic. The Gauls wore the Roman tunic instead of local vestimentary inhabits. The Roman-Gauls generally lived in the vici, small villages built like those in Italy or in villae, for the wealthier residents.

Surviving Celtic influences also infiltrated back into the Roman Imperial culture in the third century. For example, the Gaulish tunic—which gave Emperor Caracalla his surname—had not been replaced by Roman vestimentary fashion. Similarly, certain Gaulish artisan techniques, such as the barrel (more durable than the Roman amphora) and chain mail were adopted by the Romans.

The Celtic heritage also continued in the spoken language. In the fifth century, a Gaulish spelling and pronunciation of Latin are apparent in several poets and transcribers of popular farces. The last pockets of Gaulish speakers appear to have lingered until the sixth century.

Germanic placenames were first attested in limitrophe areas settled by Germanic colonizers (with Roman approval) from the fourth to fifth centuries as the Franks settled northern France and Belgium, the Alemanni in Alsace and Switzerland and the Burgundians in Savoie.

After the fall of Rome

The Roman administration finally collapsed as remaining troops were withdrawn southeast to protect Italy. Between 455 and 475, the Visigoths, the Burgundians, and the Franks assumed power in Gaul. Certain aspects of the ancient Celtic culture continued however after the fall of Roman administration.

Certain Gallo-Roman aristocratic families continued to exert power in Episcopal cities (as the Mauronitus family in Marseille, or the Bishop Gregory of Tours). The appearance of Germanic given names and family names becomes noticeable in France from the middle of the seventh century on, most notably in powerful families, indicating thus that the center of gravity had definitely shifted.

The Gallo-Roman, or Vulgar Latin, dialect of the late Roman period evolved into the dialects of the Langues d'oïl pronounced [o-il] or [o-i], and Old French in the north, and Occitan in the south.

The words "gaul" and "gaulois" continued to be used, at least in writing, until the end of the Merovingian period. Slowly, during the Carolingian period, the expression "Francie"' (first Francia, then Francia occidentalis) spread to describe the political reality of the Frankish kingdom (regnum francorum).

Legacy

Roman Gaul was one of the most important and stable provinces of the empire. It was through Gaul that other significant Roman provinces, such as Britannia Britain and Germania (Germany) were accessed. On the few occasions when Gaul was in turmoil, Britain was cut off from the imperial center.[1] After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Merovingians set themselves the task of maintaining and keeping in "working order the administrative machinery of the Romans".[2] While the Byzantine Emperor remained the main claimant to the title of "Roman Emperor," from an early date the French kings also "claimed to be the successor to the Roman Emperor."[3] Regarding the Church as the "representative of Roman civilization" they soon forged a strong alliance with the papacy, emerging as the popes' political protectors. In 800 C.E., Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor. Behind this lay the desire to maintain stability and peace across Western Europe, which had benefited from the Pax Romana under a single administration and legal code. Different states had their distinctive customs and sense of local identity but saw themselves as part of a wider space as well. The Holy Roman Empire has been described as a "revival form of supranational European integration."[4]

Even into the modern period of French history, the legacy of Roman Gaul continued to influence how the French and their rulers saw their role and place in the world. Napoleon Bonaparte wanted to re-unify the splintered Italian and German states, and to spread his common legal code across the territories he conquered. He also saw himself as a modern Roman Emperor, naming his son "King of Rome" because, he said, this had been the Roman custom. After World War II, with their former rivals, the Germans, it was the French who enthusiastically embraced the formation of the European Union regarding themselves as Europeans as well as French. Just as they had not lost their distinctive local identity as part of the ancient Roman empire, so they would not lose their French identity within the new, more unified European space. The Roman Empire had consciously tried to "superimpose a common law" while respecting the "cultural diversity … of the colonized people."[5] The concept of having a mission to spread "civilization" (mission civilisatrice)[6] French enlightenment, republicanism and democratic ideals have informed the development of an understanding of France's vision of Europe and of France's place and role in Europe. In this view, France has played a unique role in the world, as French historian Jules Michelet (1798 - 1874) put it,

"our history alone is complete. Take the history of France, with it you know the world … from Caesar to Charlemagne to Saint Louis, from Louis XIV to Napoleon, makes the history of France that of humanity as a whole." […]"Through it, in various forms, the whole moral history of humanity is perpetuated."[7]

From the Roman period onwards, France played a crucial role in the development of European culture, identity and politics; "The peculiar historical and cultural legacies of France" are in this view transposed "from the first 'nation-state' in Europe to the continent as a whole, since all European states" can be seen as "products of France's Enlightenment, republicanism and democratic heritage. As such, France had engendered Europe."[8]

Notes

- ↑ For example, during the revolt of 259 and from 286 to 188, when rival emperors, Carausius and Allectushe, controlled Britain and northern Gaul.

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm, 1910. The Encyclopædia Britannica: a Dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information. (Cambridge, UK: University Press), 907.

- ↑ Chisholm, 1910, 908.

- ↑ Angela Ward and Alan Dashwood. 1999. The Cambridge yearbook of European legal studies. (Oxford, UK: Hart Publishing. ISBN 9781841131276), 37.

- ↑ Ward and Dashwood, 1999, 37.

- ↑ Also known as "French exceptionalism." Emmanuel Godin and Tony Chafer. 2005. The French Exception. (New York, NY: Berghahn Books)

- ↑ Godin and Chafer, 2005, 5.

- ↑ Robert Shannan Peckham. 2003. Rethinking heritage: cultures and politics in Europe. (London, UK: I.B. Tauris), 86.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Caesar, Julius, and S.A. Handford. 1951. The conquest of Gaul. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140440218.

- Godin, Emmanuel, and Tony Chafer. 2005. The French exception. New York, NY: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571816849.

- King, Anthony. 1990. Roman Gaul and Germany. Exploring the Roman world. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520069893.

- Latouche, Robert. 1968. Caesar to Charlemagne: the beginning of France. London, UK: Phoenix House. ISBN 9780460077286.

- Drinkwater, J.F. 1984. Roman Gaul: the three provinces, 58 B.C.E.-AD 260. London, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 9780709903512.

- Peckham, Robert Shannan, ed. 2003. Rethinking heritage: cultures and politics in Europe. London, UK: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860647963.

- Ward, Angela and Alan Dashwood. 1999. The Cambridge yearbook of European legal studies. Oxford, UK: Hart Publishing. ISBN 9781841131276

- Woolf, Greg. 1998. Becoming Roman: the origins of provincial civilization in Gaul. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521414456.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.