Water fluoridation

Water fluoridation is the controlled addition of fluoride to a public water supply in order to reduce tooth decay. Its use in the U.S. began in the 1940s, following studies of children in a region where water is naturally fluoridated. Too much fluoridation causes dental fluorosis, which mottles or stains teeth, but U.S. researchers discovered that moderate fluoridation prevents cavities, and it is now used for about two-thirds of the U.S. population on public water systems and for about 5.7 percent of people worldwide. Although there is no clear evidence of adverse effects other than fluorosis, most of which is mild and not of aesthetic concern, water fluoridation has been contentious for ethical, safety, and efficacy reasons, and opposition to water fluoridation exists despite its support by public health organizations.

Motivation

The goal of water fluoridation is to prevent tooth decay (dental caries), one of the most prevalent chronic diseases worldwide, and one that greatly affects the quality of life of children, particularly those of low socioeconomic status. Fluoride toothpaste, dental sealants, and other techniques are also effective in preventing tooth decay.[1] Water fluoridation, when culturally acceptable and technically feasible, is said to have substantial advantages over toothpaste, especially for subgroups at high risk.[2]

Implementation

Fluoridation is normally accomplished by adding one of three compounds to drinking water:

- Hydrofluosilicic acid (H2SiF6; also known as hexafluorosilicic, hexafluosilicic, silicofluoric, or fluosilicic acid), is an inexpensive watery byproduct of phosphate fertilizer manufacture.[3]

- Sodium silicofluoride (Na2SiF6) is a powder that is easier to ship than hydrofluosilicic acid.[3]

- Sodium fluoride (NaF), the first compound used, is the reference standard.[3] It is more expensive, but is easily handled and is used by smaller utility companies.[4]

These compounds were chosen for their solubility, safety, availability, and low cost.[3] The estimated cost of fluoridation in the U.S., in 1999 dollars, is $0.72 per person per year (range: $0.17–$7.62); larger water systems have lower per capita cost, and the cost is also affected by the number of fluoride injection points in the water system, the type of feeder and monitoring equipment, the fluoride chemical and its transportation and storage, and water plant personnel expertise.[5] A 1992 census found that, for U.S. public water supply systems reporting the type of compound used, 63 percent of the population received water fluoridated with hydrofluosilicic acid, 28 percent with sodium silicofluoride, and 9 percent with sodium fluoride.[6]

Defluoridation is needed when the naturally occurring fluoride level exceeds recommended limits. It can be accomplished by percolating water through granular beds of activated alumina, bone meal, bone char, or tricalcium phosphate; by coagulation with alum; or by precipitation with lime.[7]

In the U.S. the optimal level of fluoridation ranges from 0.7 to 1.2 mg/L (milligrams per liter, equivalent to parts per million), depending on the average maximum daily air temperature; the optimal level is lower in warmer climates, where people drink more water, and is higher in cooler climates.[8] In Australia optimal levels range from 0.6 to 1.1 mg/L.[9] Some water is naturally fluoridated at optimal levels, and requires neither fluoridation nor defluoridation.[7]

Mechanism

Water fluoridation operates by creating low levels (about 0.04 mg/L) of fluoride in saliva and plaque fluid. This in turn reduces the rate of tooth enamel demineralization, and increases the rate of remineralization of the early stages of cavities.[10] Fluoride is the only agent that has a strong effect on cavities; technically, it does not prevent cavities but rather controls the rate at which they develop.[11]

Evidence basis

Existing evidence strongly suggests that water fluoridation prevents tooth decay. There is also consistent evidence that it causes fluorosis, most of which is mild and not considered to be of aesthetic concern.[9] The best available evidence shows no association with other adverse effects. However, the quality of the research on fluoridation has been generally low.[12]

Effectiveness

Water fluoridation is the most effective and socially equitable way to achieve wide exposure to fluoride's cavity-prevention effects,[9] and has contributed to dental health worldwide of children and adults.[5] A 2000 systematic review found that fluoridation was associated with a decreased proportion of children with cavities (the median of mean decreases was 14.6 percent, the range −5 percent to 64 percent), and with a decrease in decayed, missing, and filled primary teeth (the median of mean decreases was 2.25 teeth, the range 0.5 to 4.4 teeth). The evidence was of moderate quality. Many studies did not attempt to reduce observer bias, control for confounding factors, or use appropriate analysis.[12] Fluoridation also prevents cavities in adults of all ages; [13] a 2007 meta-analysis found that fluoridation prevented an estimated 27 percent of cavities in adults (range 19 percent–34 percent).[14]

The decline in tooth decay in the U.S. since water fluoridation began in the 1950s has been attributed largely to the fluoridation,[8] and has been listed as one of the ten great public health achievements of the twentieth century in the U.S.[15] Initial studies showed that water fluoridation led to reductions of 50–60 percent in childhood cavities; more recent estimates are lower (18–40 percent), likely due to increasing use of fluoride from other sources, notably toothpaste.[5] The introduction of fluoride toothpaste in the early 1970s has been the main reason for the decline in tooth decay since then in industrialized countries.[10]

In Europe, most countries have experienced substantial declines in cavities without the use of water fluoridation, indicating that water fluoridation may be unnecessary in industrialized countries.[10] For example, in Finland and Germany, tooth decay rates remained stable or continued to decline after water fluoridation stopped. Fluoridation may be more justified in the U.S. because unlike most European countries, the U.S. does not have school-based dental care, many children do not attend a dentist regularly, and for many U.S. children water fluoridation is the prime source of exposure to fluoride.[16]

Although a 1989 workshop on cost effectiveness of caries prevention concluded that water fluoridation is one of the few public health measures that saves more money than it costs, little high-quality research has been done on the cost-effectiveness and solid data are scarce.[5][8]

Safety

At the commonly recommended dosage, the only clear adverse effect is dental fluorosis, most of which is mild and not considered to be of aesthetic concern. Compared to unfluoridated water, fluoridation to 1 mg/L is estimated to cause fluorosis in one of every 6 people, and to cause fluorosis of aesthetic concern in one of every 22 people.[12] Fluoridation has little effect on risk of bone fracture (broken bones); it may result in slightly lower fracture risk than either excessively high levels of fluoridation or no fluoridation.[9] There is no clear association between fluoridation and cancer, deaths due to cancer, bone cancer, or osteosarcoma.[9]

In rare cases improper implementation of water fluoridation can result in overfluoridation, resulting in fluoride poisoning. For example, in Hooper Bay, Alaska in 1992, a combination of equipment and human errors resulted in one of the two village wells being overfluoridated, causing one death and an estimated 295 nonfatal cases of fluoride intoxication.[17]

Adverse effects that lack sufficient evidence to reach a scientific conclusion[9] include:

- Like other common water additives such as chlorine, hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride decrease pH, and cause a small increase of corrosivity; this can easily be resolved by adjusting the pH upward.[18]

- Some reports have linked hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride to increased human lead uptake;[19] these have been criticized as providing no credible evidence.[18]

- Arsenic and lead may be present in fluoride compounds added to water, but there is no credible evidence that this is of concern: concentrations are below measurement limits.[18]

The effect of water fluoridation on the environment has been investigated, and no adverse effects have been established. Issues studied have included fluoride concentrations in groundwater and downstream rivers; lawns, gardens, and plants; consumption of plants grown in fluoridated water; air emissions; and equipment noise.[18]

Politics

Almost all major health and dental organizations support water fluoridation, or have found no association between fluoridation and adverse effects.[20][21] These organizations include the World Health Organization,[22] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[5] the U.S. Surgeon General,[23] and the American Dental Association.[24]

Despite support by public health organizations and authorities, efforts to introduce water fluoridation meet considerable opposition whenever it is proposed.[20] Controversies include disputes over fluoridation's benefits and the strength of the evidence basis for these benefits, the difficulty of identifying harms, legal issues over whether water fluoridation is a medicine, and the ethics of mass intervention.[25] Opposition campaigns involve newspaper articles, talk radio, and public forums. Media reporters are often poorly equipped to explain the scientific issues, and are motivated to present controversy regardless of the underlying scientific merits. Internet websites, which are increasingly used by the public for health information, contain a wide range of material about fluoridation ranging from factual to fraudulent, with a disproportionate percentage opposed to fluoridation. Conspiracy theories involving fluoridation are common, and include claims that fluoridation is part of a Communist or New World Order plot to take over the world, that it was pioneered by a German chemical company to make people submissive to those in power, that it is backed by the sugar or aluminum or phosphate industries, or that it is a smokescreen to cover failure to provide dental care to the poor.[20] Specific antifluoridation arguments change to match the spirit of the time.[26]

Use around the world

About 5.7 percent of people worldwide drink fluoridated water;[25] this includes 61.5 percent of the U.S. population.[28] 12 million people in Western Europe have fluoridated water, mainly in England, Spain, and Ireland. France, Germany, and some other European countries use fluoridated salt instead; the Netherlands, Sweden, and a few other European countries rely on fluoride supplements and other measures.[29] The justification for water fluoridation is analogous to the use of iodized salt for the prevention of goiters. China, Japan, the Philippines, and India do not fluoridate water.[30]

Australia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Canada, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, Israel, Malaysia, and New Zealand have introduced water fluoridation to varying degrees. Germany, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland have discontinued water fluoridation schemes for reasons which are not systematically available.[25]

Alternative methods

Water fluoridation is one of several methods of fluoride therapy; others include fluoridation of salt, milk, and toothpaste.[31]

The effectiveness of salt fluoridation is about the same as water fluoridation, if most salt for human consumption is fluoridated. Fluoridated salt reaches the consumer in salt at home, in meals at school and at large kitchens, and in bread. For example, Jamaica has just one salt producer, but a complex public water supply; it fluoridated all salt starting in 1987, resulting in a notable decline in the prevalence of cavities. Universal salt fluoridation is also practiced in Columbia, Jamaica, and the Canton of Vaud in Switzerland; in France and Germany fluoridated salt is widely used in households but unfluoridated salt is also available. Concentrations of fluoride in salt range from 90 mg/kg to 350 mg/kg, with studies suggesting an optimal concentration of around 250 mg/kg.[31]

Milk fluoridation is being practiced by the Borrow Foundation in some parts of Bulgaria, Chile, Peru, Russia, Thailand and the United Kingdom. For example, milk-powder fluoridation is used in Chilean rural areas where water fluoridation is not technically feasible.[32] These programs are aimed at children, and have neither targeted nor been evaluated for adults.[31] A 2005 systematic review found insufficient evidence to support the practice, but also concluded that studies suggest that fluoridated milk benefits schoolchildren, especially their permanent teeth.[33]

Some dental professionals are concerned that the growing use of bottled water may decrease the amount of fluoride exposure people will receive.[34] Some bottlers such as Danone have begun adding fluoride to their water.[35] On April 17, 2007, [1] Medical News Today stated, "There is no correlation between the increased consumption of bottled water and an increase in cavities."[36] In October 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a health claim notification permitting water bottlers to claim that fluoridated bottled water can promote oral health. The claims are not allowed to be made on bottled water marketed to infants.[37]

History

The history of water fluoridation can be divided into three periods. The first (c. 1901–1933) was research into the cause of a form of mottled tooth enamel called "Colorado brown stain," which later became known as fluorosis. The second (c. 1933–`945) focused on the relationship between fluoride concentrations, fluorosis, and tooth decay. The third period, from 1945 on, focused on adding fluoride to community water supplies.[38]

Colorado brown stain

While the use of fluorides for prevention of dental caries (cavities) was discussed in the nineteenth century in Europe,[39] community water fluoridation in the United States is partly due to the research of Dr. Frederick McKay, who pressed the dental community for an investigation into what was then known as "Colorado Brown Stain."[40] The condition, now known as dental fluorosis, when in its severe form is characterized by cracking and pitting of the teeth.[41][42][43] Of 2,945 children examined in 1909 by Dr. McKay, 87.5 percent had some degree of stain or mottling. All the affected children were from the Pikes Peak region. Despite the negative impact on the physical appearance of their teeth, the children with stained, mottled and pitted teeth also had fewer cavities than other children. McKay brought this to the attention of Dr. G.V. Black, and Black's interest was followed by greater interest within the dental profession.

Initial hypotheses for the staining included poor nutrition, overconsumption of pork or milk, radium exposure, childhood diseases, or a calcium deficiency in the local drinking water.[40] In 1931, researchers from the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) concluded that the cause of the Colorado stain was a high concentration of fluoride ions in the region's drinking water (ranging from 2 to 13.7 mg/L) and areas with lower concentrations had no staining (1 mg/L or less).[44] Pikes Peak's rock formations contained the mineral cryolite, one of whose constituents is fluorine. As the rain and snow fell, the resulting runoff water dissolved fluoride which made its way into the water supply.

Dental and aluminum researchers then moved toward determining a relatively safe level of fluoride chemicals to be added to water supplies. The research had two goals: (1) to warn communities with a high concentration of fluoride of the danger, initiating a reduction of the fluoride levels in order to reduce incidences of fluorosis, and (2) to encourage communities with a low concentration of fluoride in drinking water to add fluoride chemicals in order to help prevent tooth decay. By 2006, 69.2 percent of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5 percent of the total U.S. population; 3.0 percent of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.[28]

Early studies

A study of varying amounts of fluoride in water was led by Dr. H. Trendley Dean, a dental officer of the U.S. Public Health Service.[45][46] In 1936 and 1937, Dr. Dean and other dentists compared statistics from Amarillo, which had 2.8 - 3.9 mg/L fluoride content, and low fluoride Wichita Falls. The data is alleged to show less cavities in Amarillo children, but the studies were never published.[47] Dr. Dean's research on the fluoride-dental caries relationship, published in 1942, included 7,000 children from 21 cities in Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The study concluded that the optimal amount of fluoride which minimized the risk of severe fluorosis but had positive benefits for tooth decay was 1 mg per day, per adult. Although fluoride is more abundant in the environment today, this was estimated to correlate with the concentration of 1 mg/L.

In 1937, dentists Henry Klein and Carroll E. Palmer had considered the possibility of fluoridation to prevent cavities after their evaluation of data gathered by a Public Health Service team at dental examinations of Native American children.[48] In a series of papers published afterwards (1937-1941), yet disregarded by his colleagues within the U.S.P.H.S., Klein summarized his findings on tooth development in children and related problems in epidemiological investigations on caries prevalence.

In 1939, Dr. Gerald J. Cox[49] conducted laboratory tests using rats that were fed aluminum and fluoride. Dr. Cox suggested adding fluoride to drinking water (or other media such as milk or bottled water) in order to improve oral health.[50]

In the mid 1940s, four widely cited studies were conducted. The researchers investigated cities that had both fluoridated and unfluoridated water. The first pair was Muskegon, Michigan and Grand Rapids, Michigan, making Grand Rapids the first community in the world to add fluoride chemicals to its drinking water to try to benefit dental health on January 25, 1945.[51] Kingston, New York was paired with Newburgh, New York.[52] Oak Park, Illinois was paired with Evanston, Illinois. Sarnia, Ontario was paired with Brantford, Ontario, Canada.[53]

In 1952 Nebraska Representative A.L. Miller complained that there had been no studies carried out to assess the potential adverse health risk to senior citizens, pregnant women or people with chronic diseases from exposure to the fluoridation chemicals.[47] A decrease in the incidence of tooth decay was found in some of the cities which had added fluoride chemicals to water supplies. The early comparison studies would later be criticized as, "primitive," with a, "virtual absence of quantitative, statistical methods...nonrandom method of selecting data and…high sensitivity of the results to the way in which the study populations were grouped…" in the journal Nature.[54]

Opposition to water fluoridation

Opposition to water fluoridation refers to activism against the fluoridation of public water supplies. The controversy occurs mainly in English-speaking countries, as Continental Europe does not practice water fluoridation, although some continental countries fluoridate salt.[55] Most of the health effects are associated with water fluoridation at levels above the recommended concentration of 0.7 – 1.2 mg/L (0.7 for hot climate, 1.2 in cool climates), but those organizations and individuals opposed raise concerns that the intake is not easily controlled, and that children, small individuals, and others may be more susceptible to health problems. Those opposed also argue that water fluoridation is ineffective,[56] may cause serious health problems,[57][58][59] and imposes ethical issues.[60] Opposition to fluoridation has existed since its initiation in the 1940s.[55] During the 1950s and 1960s, some opponents of water fluoridation also put forward conspiracy theories describing fluoridation as a communist plot to undermine public health.[61] Sociologists used to view opposition to water fluoridation as an example of misinformation. However, contemporary critiques of this position have pointed out that this position rests on an uncritical attitude toward scientific knowledge.[55]

Ethics

Many who oppose water fluoridation consider it to be a form of compulsory mass medication. They argue that consent of all water consumers cannot be achieved, nor can water suppliers accurately control the exact levels of fluoride that individuals receive, nor monitor their response.[60] It is also argued that, because of the negative health effects of fluoride exposure, mandatory fluoridation of public water supplies is a breach of ethics and a human rights violation.

In the United Kingdom the Green Party refers to fluoride as a poison, claim that water fluoridation violates Article 35 of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights, is banned by the UK poisons act of 1972, violates Articles 3 and 8 of the Human Rights Act and raises issues under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.[62]

Water fluoridation has also been criticized by Cross and Carton for violating the Nuremberg Code and the Council of Europe's Biomedical Convention of 1999.[63] Dentistry professor David Locker and philosopher Howard Cohen argued that the moral status for advocating water fluoridation is "at best indeterminate" and could even be considered immoral because it infringes upon autonomy based on uncertain evidence, with possible negative effects.[64]

The precautionary principle

In an analysis published in the March 2006 issue of the Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice, the authors examine the water fluoridation controversy in the context of the precautionary principle. The authors note that:

- There are other ways of delivering fluoride besides the water supply;

- Fluoride does not need to be swallowed to prevent tooth decay;

- Tooth decay has dropped at the same rate in countries with, and without, water fluoridation;

- People are now receiving fluoride from many other sources besides the water supply;

- Studies indicate fluoride’s potential to cause a wide range of adverse, systemic effects;

- Since fluoridation affects so many people, “one might accept a lower level of proof before taking preventive actions.”[65]

Potential health risks

Health risks are generally associated with fluoride intake levels above the commonly recommended dosage, which is accomplished by fluoridating the water at 0.7 – 1.2 mg/L (0.7 for hot climates, 1.2 in cool climates). This was based on the assumption that adults consumes 2 L of water per day,[66] but may a daily fluoride dose of between 1 – 3 mg/day, as men are recommended to drink 3 liters/day and women 2.2 liters/day.[67] In 1986 the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for fluoride at a concentration of 4 milligrams per liter (mg/L), which is the legal limit of fluoride allowed in the water. In 2006, a 12-person committee of the US National Research Council (NRC) reviewed the health risks associated with fluoride consumption[66] and unanimously concluded that the maximum contaminant level of 4 mg/L should be lowered. The EPA has yet to act on the NRC's recommendation.[68][69] The limit was previously 1.4 – 2.4 mg/L, but it was raised to 4 mg/L in 1985.[70]

Opposition groups express the greatest concern for vulnerable populations, and the National Research Council states that children have a higher daily average intake than adults per kg of bodyweight.[66] Those who work outside or have kidney problems will also drink more water. Of the following health problems, osteosarcoma, a rare bone disease affecting male children, is strictly associated with the recommended dosage of fluoride. The weight of the evidence does not support a relationship.[71] However, a study performed as a doctoral thesis, which is described as the most rigorous yet by the Washington Post, found a relationship among young boys,[72] but then the Harvard professor who advised the doctoral students determined that the results were not highly correlative enough to have evidentiary value; the professor then was investigated but exonerated by the federal government's Office of Research Integrity (ORI).[73] An epidemiological connection between areas with high intake of silicofluorides and increased lead blood levels in children has been observed in areas fluoridated at the recommended dosage.[74][75] A 2007 update on this study confirmed the result and noted that silicofluorides, fluosilicic acid and sodium fluosilicate are used to fluoridate over 90 percent of US fluoridated municipal water supplies.[76]

Chemistry professor Paul Connett, the executive director of the Fluoride Action Network, points out that dosages cannot be controlled, so he believes that many of the health effects observed at levels above 1 mg/L are relevant for 1 mg/L. He highlights the issues raised by the 2006 report in the form uncertainties, data gaps, and a reduced margin of safety.[77] A panel member of the report, Kathleen M. Thiessen, writes that the report does seem relevant to the debate, and that the "margin of safety between 1 mg/L and 4 mg/L is very low" because of the uncontrolled nature of the dosage.[78] In her opinion fluoride intake should be minimized. Another panel member, Robert Isaacson, stated that "this report should be a wake-up call" and said that the possible effects on the endocrine gland and hormones are "something that I wouldn’t want to happen to me if I had any say in the matter."[79] John Dull, the chair of the panel, stated that "the thyroid changes worry me … we’ve gone with the status quo regarding fluoride for many years—for too long, really—and now we need to take a fresh look … I think that’s why fluoridation is still being challenged so many years after it began. In the face of ignorance, controversy is rampant".[57]Hardy Limeback, another panel member, stated "the evidence that fluoridation is more harmful than beneficial is now overwhelming and policy makers who avoid thoroughly reviewing recent data before introducing new fluoridation schemes do so at risk of future litigation".[80]

Efficacy

In the past twenty years, a body of research has developed which indicates that the anticaries effects of fluoride on the teeth are largely derived from topical application (brushing) rather than systemic (swallowing).[66] These findings are disputed by some researchers and public health agencies such as the CDC. The evidence for water fluoridation reducing caries was examined in a systematic review of 30 studies by the University of York. The researchers concluded that the best evidence available, which was only of moderate, B level quality, indicated that fluoride reduces caries with a median effect of approximately 15%, with results ranging from a great reduction to a small increase in caries. They stated that "it is surprising to find that little high quality research has been undertaken",[81] and expressed concern over the "continuing misinterpretations of the evidence".[82] These concerns were repeated in a 2007 article in the British Medical Journal.[83] The York Review did not assess the overall cost-benefits of fluoridation, stating that the research is not strong enough to make confident statements about potential harmful effects, and concluded that these factors would need to be included in a decision to fluoridate water.

The largest study of water fluoridation's efficacy was conducted by the National Institute of Dental Research in 1988. The data was reanalyzed by John A. Yiamouyiannis, whose results indicated that no statistically significant difference in tooth decay rates among children in fluoridated and non-fluoridated communities existed.[84]

Statements against

Since 1985, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) headquarters' union has expressed concerns about fluoride. In 2005, eleven environmental protection agency EPA employee unions, representing over 7000 environmental and public health professionals of the Civil Service, called for a halt on drinking water fluoridation programs across the USA and asked EPA management to recognize fluoride as posing a serious risk of causing cancer in people. Among the union's concerns are what they contend is a cover-up of evidence from Harvard School of Dental Medicine linking fluoridation with an elevated risk of osteosarcoma in boys, a rare but fatal bone cancer.[85] However, the professor accused of the cover-up was exonerated by the federal Office of Research Integrity.[73]

In addition, over 1,730 health industry professionals, including one Nobel prize winner in medicine (Arvid Carlsson), doctors, dentists, scientists and researchers from a variety of disciplines are calling for an end to water fluoridation in an online petition to Congress.[86] The petition signers express concern for vulnerable groups like "small children, above average water drinkers, diabetics, and people with poor kidney function," who they believe may already be overdosing on fluoride.[86] Another concern that the petition signers share is, "The admission by federal agencies, in response to questions from a Congressional subcommittee in 1999-2000, that the industrial grade waste products used to fluoridate over 90% of America's drinking water supplies (fluorosilicate compounds) have never been subjected to toxicological testing nor received FDA approval for human ingestion."[86] The petition was sponsored by the Fluoride Action Network of Canton, New York, the most active anti-fluoridation organization in North America.

Their petition highlights eight recent events that they say mandates a moratorium on water fluoridation, including a 500-page review of fluoride’s toxicology that was published in 2006 by a distinguished panel appointed by the National Research Council of the National Academies.[66] While the NRC report did not specifically examine artificially fluoridated water, it concluded that the EPA's safe drinking water standard of 4 parts per million (ppm) for fluoride is unsafe and should be lowered. Despite over 60 years of water fluoridation in the U.S, there are no double-blind studies which prove fluoride's effectiveness in tooth decay. The panel reviewed a large body of literature in which fluoride has a statistically significant association with a wide range of adverse effects.[87]

A separate petition that calls on the United States congress to halt the practice of fluoridation has received over 12,300 signatures. [88]

In his 2004 book The Fluoride Deception, author Christopher Bryson claims that "industrial interests, concerned about liabilities from fluoride pollution and health effects on workers, played a significant role in the early promotion of fluoridation.[89]

Dr. Hardy Limeback, BSc, PhD, DDS was one of the 12 scientists who served on the National Academy of Sciences panel that issued the aforementioned report, Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of the EPA's Standards. Dr. Limeback is an associate professor of dentistry and head of the preventive dentistry program at the University of Toronto. He detailed his concerns in an April 2000 letter titled, "Why I am now officially opposed to adding fluoride to drinking water".[56]

In a presentation to the California Assembly Committee of Environmental Safety and Toxic Materials, Dr. Richard Foulkes, B.A., M.D., former special consultant to the Minister of Health of British Columbia, revealed:

The [water fluoridation] studies that were presented to me were selected and showed only positive results. Studies that were in existence at that time that did not fit the concept that they were "selling," were either omitted or declared to be "bad science." The endorsements had been won by coercion and the self-interest of professional elites. Some of the basic "facts" presented to me were, I found out later, of dubious validity. We are brought up to respect these persons in whom we have placed our trust to safeguard the public interest. It is difficult for each of us to accept that these may be misplaced.[90]

On April 15, 2008, the United States National Kidney Foundation (NKF) updated their position on fluoridation for the first time since 1981.[91][92] Formerly a supporter of water fluoridation, the NKF now takes a neutral position on the practice.

The International Chiropractors Association opposes mass water fluoridation, considering it "possibly harmful and deprivation of the rights of citizens to be free from unwelcome mass medication."[93]

Use throughout the world

Water fluoridation is used in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, and a handful of other countries. The following developed nations previously fluoridated their water, but stopped the practice, with the years when water fluoridation started and stopped in parentheses:

- German Federal Republic (1952-1971)

- Sweden (1952-1971)

- Netherlands (1953-1976)

- Czechoslovakia (1955-1990)

- German Democratic Republic (1959-1990)

- Soviet Union (1960-1990)

- Finland (1959-1993)

- Japan (1952-1972)

In 1986 the journal Nature reported, "Large temporal reductions in tooth decay, which cannot be attributed to fluoridation, have been observed in both unfluoridated and fluoridated areas of at least eight developed countries."[94]

In areas with complex water sources, water fluoridation is more difficult and more costly. Alternative fluoridation methods have been proposed, and implemented in some parts of the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) is currently assessing the effects of fluoridated toothpaste, milk fluoridation and salt fluoridation in Africa, Asia, and Europe. The WHO supports fluoridation of water in some areas, and encourages removal of fluoride where fluoride content in water is too high. [95]

History

The use of fluorides for prevention of dental caries (cavities) was discussed in the nineteenth century in Europe.[39] The discovery of relatively high concentrations of fluorine in teeth led researchers to investigate further. In 1925 researchers fed fluoride to rats and concluded that fluoride had a negative effect on their teeth.[96] In 1937, Danish researcher Kaj Roholm published Fluorine Intoxication: A Clinical-hygienic Study, with a Review of the Literature and Some Experimental Investigations, concluding that fluoride weakened the teeth and urging against the use of fluorides in children.[89] In the 1930s, negative research on the effects of low-dose fluoride was appearing in the US as well, including a 1933 review by the US Department of Agriculture. A senior USDA toxicologist, Floyd DeEds, stated that "only recently, that is within the last ten years, has the serious nature of fluoride toxicity been realized, particularly with regard to chronic intoxication." Both Roholm and DeEds identified the aluminum industry as a major source of the pollution and toxicity.[89] DeEds noted that the mottling of the teeth occurred not only in areas with natural fluoride, but also areas nearby to aluminum plants, where Alcoa chemists reported no natural fluoride in the water.

Conspiracy theories

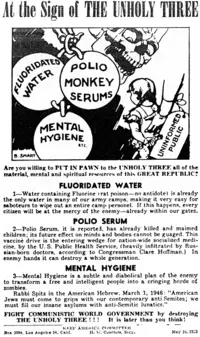

Water fluoridation has frequently been the subject of conspiracy theories. During the "Red Scare" in the United States during the late 1940s and 1950s, and to a lesser extent in the 1960s, activists on the far right of American politics routinely asserted that fluoridation was part of a far-reaching plot to impose a socialist or communist regime. They also opposed other public health programs, notably mass vaccination and mental health services.[97] Their views were influenced by opposition to a number of major social and political changes that had happened in recent years: the growth of internationalism, particularly the UN and its programs; the introduction of social welfare provisions, particularly the various programs established by the New Deal; and government efforts to reduce perceived inequalities in the social structure of the United States.[98]

Some took the view that fluoridation was only the first stage of a plan to control the American people: "Already there is serious talk of inserting birth control drugs in public water supplies, and growing whispers of a happier and more manageable society is so-called behavioral drugs are mass-applied." Fluoridation, it was claimed, was merely a stepping-stone on the way to implementing more ambitious programs. Others asserted the existence of a plot by communists and the United Nations to "deplete the brainpower and sap the strength of a generation of American children." Dr. Charles Bett, a prominent anti-fluoridationist, charged that fluoridation was "better THAN USING THE ATOM BOMB because the atom bomb has to be made, has to be transported to the place it is to be set off while POISONOUS FLUORINE has been placed right beside the water supplies by the Americans themselves ready to be dumped into the water mains whenever a Communist desires!" Similarly, a right-wing newsletter, the American Capsule News, claimed that "the Soviet General Staff is very happy about it. Anytime they get ready to strike, and their 5th column takes over, there are tons and tons of this poison "standing by" municipal and military water systems ready to be poured in within 15 minutes."[61]

This viewpoint led to major controversies over public health programs in the US, most notably in the case of the Alaska Mental Health Enabling Act controversy of 1956.[99] In the case of fluoridation, the controversy had a direct impact on local programs. During the 1950s and 1960s, referendums on introducing fluoridation were defeated in over a thousand Florida communities. Although the opposition was overcome in time, it was not until as late as the 1990s that fluoridated water was drunk by the majority of the population of the United States.[97]

The communist conspiracy argument declined in influence by the mid-1960s, becoming associated in the public mind with irrational fear and paranoia. It was lampooned in Stanley Kubrick's 1964 film Dr. Strangelove, in which a character initiates a nuclear war in the hope of thwarting a communist plot to "sap and impurify" the "precious bodily fluids" of the American people with fluoridated water. Similar satires appeared in other movies, such as 1967's In Like Flint, in which a character's fear of fluoridation is used to indicate that he is insane. Even some anti-fluoridationists recognized the damage that the conspiracy theorists were causing; Dr. Frederick Exner, an anti-fluoridation campaigner in the early 1960s, told a conference: "most people are not prepared to believe that fluoridation is a communist plot, and if you say it is, you are successfully ridiculed by the promoters. It is being done, effectively, every day … some of the people on our side are the fluoridators' 'fifth column'."[61]

Court cases in the United States

Fluoridation has been the subject of many court cases. Activists have sued municipalities, asserting that their rights to consent to medical treatment, privacy, and due process are infringed by mandatory water fluoridation.[63] Individuals have sued municipalities for a number of illnesses that they believe were caused by fluoridation of the city's water supply. So far, the majority of courts have held in favor of cities in such cases, finding no or only a tenuous connection between health problems and widespread water fluoridation.[100] To date, no federal appellate court or state court of last resort (i.e., state supreme court) has found water fluoridation to be unlawful.[101]

See also

Notes

- ↑ R.H. Selwitz A.I. Ismail, and N.B. Pitts. 2007. Dental caries. Lancet. 369(9555):51–59.

- ↑ P.E. Petersen and M.A. Lennon. 2004. Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in the 21st century: the WHO approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 32(5):319–321. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 T.G. Reeves, 1986. Water fluoridation: a manual for engineers and technicians. Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Nicholson, Czarnecka, and Tressaud. 2008. pages 333–78.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 50(RR-14):1–42. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Fluoridation census 1992. Division of Oral Health, National Center for Prevention Services, CDC. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Taricska, Wang, Hung, Li, Wang, Hung, and Shammas. 2006. 293–315.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 W. Bailey, L. Barker, K. Duchon, and W. Maas. 2008. Populations receiving optimally fluoridated public drinking water—United States, 1992–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 57(27):737–741. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 C.A. Yeung, 2008. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation. Evid Based Dent. 9(2):39–43.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 G. Pizzo, M.R. Piscopo, I. Pizzo, and G. Giuliana. 2007. Community water fluoridation and caries prevention: a critical review. Clin Oral Investig. 11(3):189–193.

- ↑ T. Aoba, and O. Fejerskov. 2002. Dental fluorosis: chemistry and biology. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 13(2):155–170.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 M.S. McDonagh, P.F. Whiting, P.M. Wilson et al. 2000. Systematic review of water fluoridation. BMJ. 321(7265):855–859. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Yeung, 2007. Fluoride prevents caries among adults of all ages. Evid Based Dent. 8(3):72–3.

- ↑ S.O. Griffin, E. Regnier, P.M. Griffin, and V. Huntley. 2007. Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults. J Dent Res. 86(5):410–415.

- ↑ Top 10 U.S. public health achievements in twentieth century:

- CDC. 1999. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 48(12):241–243. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. 1999. Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 48(41):933–940. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ B.A. Burt, and S.L. Tomar. 2007. "Changing the face of America: water fluoridation and oral health," in J.W. Ward, C. Warren, (eds.) 2007. Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195150694), 307–322.

- ↑ B.D. Gessner, M. Beller, J.P. Middaugh, and G.M. Whitford. 1994. Acute fluoride poisoning from a public water system. N Engl J Med. 330(2):95–99. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 H.F. Pollick, 2004. Water fluoridation and the environment: current perspective in the United States. Int J Occup Environ Health. 10(3):343–350. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ M.J. Coplan, S.C. Patch, R.D. Masters, and M.S. Bachman. 2007. Confirmation of and explanations for elevated blood lead and other disorders in children exposed to water disinfection and fluoridation chemicals. Neurotoxicology. 28(5):1032–1042.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 J.M. Armfield, 2007. When public action undermines public health: a critical examination of antifluoridationist literature. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 4:25.

- ↑ National and international organizations that recognize the public health benefits of community water fluoridation for preventing dental decay. American Dental Association. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ P.E. Petersen, 2008. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health—World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 58(3):115–121. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Richard Carmona, 2004. Surgeon General's statement on community water fluoridation. ;;U.S. Public Health Service;;. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Fluoridation facts.;; American Dental Association;;. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 K.K. Cheng, I. Chalmers, and T.A. Sheldon. 2007. Adding fluoride to water supplies. BMJ. 335(7622):699–702. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ E. Newbrun, 1996. The fluoridation war: a scientific dispute or a religious argument? J Public Health Dent. 56(5):246–252.

- ↑ R.F. Klein, 2008. Healthy People 2010 Progress Review, Focus Area 21, Oral Health. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Water fluoridation statistics for 2006. CDC. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ The British Fluoridation Society. 2004, 55–80.

- ↑ Colin Ingram. 2006. The Drinking Water Book. (Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts. ISBN 9781587612572), 15-16.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 S. Jones. B.A. Burt, P.E. Petersen, and M.A. Lennon. 2005. The effective use of fluorides in public health. Bull World Health Organ. 83(9):670–676. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ J. Bánóczy, and A.J. Rugg-Gunn. 2006. Milk—a vehicle for fluorides: a review. Rev Clin Pesq Odontol. 2(5–6):415–426. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ C.A. Yeung, J.L. Hitchings, T.V. Macfarlane, A.G. Threlfall, M. Tickle, and A.M. Glenny. 2005. Fluoridated milk for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):CD003876.

- ↑ Michael Smith, Bottled Water Cited as Contributing to Cavity Comeback. MedPage Today. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Press release. Water Industry News. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Bottled Water And Fluoride Facts. Medical News Today. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Why was the interim guidance on infant formula and fluoride issued? American Dental Association. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ L.W. Ripa, 1993. A half-century of community water fluoridation in the United States: review and commentary. J Public Health Dent. 53(1):17–44. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Peter Meiers, Early Fluoride research in Europe. Fluoride History. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 History of Dentistry in the Pikes Peak Region. Colorado Springs Dental Society. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ The Story of Fluoridation. nidr.nih.gov. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ How does fluoride affect teeth? Does ingesting fluoride in drinking water affect teeth more than fluoride toothpaste? McGraw-Hill's AccessScience. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Report Judges Allowable Fluoride Levels in Water. NPR. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Peter Meiers, The Bauxite Story - A look at ALCOA. Fluoride History. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ H.T. Dean, 1934. Classification of mottled enamel diagnosis. Journal of the American Dental Association. 21:1421-1426.

- ↑ H.T. Dean, 1936. Chronic endemic dental fluorosis. Journal of the American Dental Association. 16:1269-1273.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Questionable Fluoride Safety Studies: Bartlett - Cameron, Newburgh - Kingston. Fluoride History. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ H. Klein and C.E. Palmer. 1937. Dental caries in American Indian children. Public Health Bulletin. 239.

- ↑ Peter Meiers, Gerald Judy Cox. Fluoride History. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ G.J. Cox, M.C. Matuschak, S.F. Dixon, M.L. Dodds, and W.E. Walker. 1939. Experimental dental caries IV. Fluorine and its relation to dental caries. Journal of Dental Research. 18:481-490.

- ↑ After 60 Years of Success, Water Fluoridation Still Lacking in Many Communities. Medical News Today. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ D.B. Ast, D.J. Smith, B. Wacks, and K.T. Cantwell. 1956. Newburgh-Kingston caries-fluorine study XIV. Combined clinical and roentgenographic dental findings after ten years of fluoride experience. Journal of the American Dental Association. 52:314-325.

- ↑ H. Brown, and M. Poplove. 1963. The Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford Fluoridation Caries Study: Final Survey, 1963. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 56:319–324.

- ↑ Mark Diesendorf, 1986. The mystery of declining tooth decay. Nature. 322:125-129.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 B. Martin, 1989. The sociology of the fluoridation controversy: a reexamination. Sociological Quarterly. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Hardy Limeback, 2000. Why I am now officially opposed to adding fluoride to drinking water. Fluoride Alert. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Second Thoughts on Fluoride. Scientific American. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ John Colquhoun, 1998. Why I changed my mind about water fluoridation. Fluoride. 31(2):103–118.

- ↑ A Bibliography of Scientific Literature on Fluoride. Second look. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 The Fluoride Debate: Question 34. Fluoride Debate. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Robert Johnston. 2004. The Politics of Healing. (New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0415933390), 136.

- ↑ Water fluoridation contravenes UK law, EU directives and the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. UK Green Party. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 D.W. Cross, and R.J. Carton. 2003. Fluoridation: a violation of medical ethics and human rights. Int J Occup Environ Health. 9(1):24-29. - "The ethical validity of fluoridation policy does not stand up to scrutiny relative to the Nuremberg Code and other codes of medical ethics, including the Council of Europe's Biomedical Convention of 1999." Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ H. Cohen, and D. Locker. 2002. The Science and Ethics of Water Fluoridation. J Can Dent Assoc 2001. 67(10):578-580. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ J. Tickner, and M. Coffin. 2006. What does the precautionary principle mean for evidence-based dentistry? Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice. 6:6-15.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 Committee on Fluoride in Drinking Water, National Research Council. 2006. Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA's Standards. National Academies Press. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Water: How much should you drink every day? Mayo Clinic. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Community Water Fluoridation, FAQ. EPA. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Setting Standards for Safe Drinking Water. EPA. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ EPA Fluoride Standards: Focus on Fluorosis. Fluoride Alert. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ CDC Statement on Water Fluoridation and Osteosarcoma. CDC. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Professor at Harvard Is Being Investigated. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 At the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, One Professor’s Fluoride Scandal Stinks. The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Adverse Health and Behavior from Silicoflourides. dartmouth.edu.

- ↑ R.D. Masters, M.J. Coplan, B.T. Hone, and J.E. Dykes. 2000. Dartmouth press release. Neurotoxicology. 21(6):1091–1100.

- ↑ M.J. Coplan, S.C. Patch, R.D. Masters, and M.S. Bachman. 2007. Confirmation of and explanations for elevated blood lead and other disorders in children exposed to water disinfection and fluoridation chemicals. Neurotoxicology. 28(5):1032–1042.

- ↑ Paul Connett, The relevance of the NRC Report to fluoridation. Fluoride Action Network. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ K.M. Thiessen, 2006. Correspondence. Fluoride Alert. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ N. Budnick, 2006. Fluoride foes get validation. Portland Tribune. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ H. Limeback, 2006. GUEST VIEW: The evidence that fluoride is harmful is overwhelming. The Standard Times. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Executive Summary. York Review. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Should fluoride be forced upon us? BBC News. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Cheng, K.K. et al. 2007. Adding fluoride to water supplies. British Medical Journal. 335(7622):699-702.

- ↑ NIDR Study on Fluoridation. icnr.com. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Fluoride Summary. nteu280.org. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Professionals' Statement Calling For An End To Water Fluoridation. Fluoride Alert. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA's Standards. nap.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Home page. Fluoride Action Network. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Bryson. 2004.

- ↑ Richard G. Foulkes, 1995. Presentation to the California Assembly Committee of Environmental Safety and Toxic Materials. Sonic. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Kidney Patients Should be Notified of Potential Risk from Fluorides and Fluoridated Drinking Water. Organic Consumers Association. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Fluoride Intake in Chronic Kidney Disease. National Kidney Foundation. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ ICA Policy Position Statements. International Chiropractors Association. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Mark Diesendorf, 1986. The mystery of declining tooth decay. Nature. 322:125-129. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ WHO World Oral Health Report. World Health Organization. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Elmer Verner McCollum, et al. 1925. The effect of additions of fluorine to the diet of the rat on the quality of the teeth. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 63(3):553–562. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Robin Marantz Henig. 1997 The People's Health. (Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0309054923), 85.

- ↑ Richard H. Rovere. 1959. Senator Joe McCarthy. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520204727), 21–22.

- ↑ Judd Marmor, 1974. "Psychodynamics of Group Opposition to Mental Health Programs," in Psychiatry in Transition. (New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. ISBN 0876300700).

- ↑ Beck v. City Council of Beverly Hills, 30 Cal. App. 3d 112, 115 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 1973) ("Courts through the United States have uniformly held that fluoridation of water is a reasonable and proper exercise of the police power in the interest of public health. The matter is no longer an open question."

- ↑ Edwin Pratt, Raymond D. Rawson, and Mark Rubin. 2002. Fluoridation at Fifty: What Have We Learned. J.L. Med. & Ethics. 117:119.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bryson, Christopher. 2004. The Fluoride Deception. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1583225269.

- Burt, B.A., and S.L. Tomar. 2007. "Changing the face of America: water fluoridation and oral health," in J.W. Ward, C. Warren eds. 2007. Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195150694.

- Fawell, John Wesley. 2006. Fluoride in drinking-water. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization. ISBN 9241563192.

- Henig, Robin Marantz. 1997. The People's Health. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0309054923.

- Ingram, Colin. 2006. The Drinking Water Book. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts. ISBN 9781587612572.

- Johnston, Robert D. 2004. The Politics of Healing. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0415933390.

- Marmor, Judd. 1974. "Psychodynamics of Group Opposition to Mental Health Programs," in Psychiatry in Transition. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. ISBN 0876300700.

- Nicholson, J.W., and B. Czarnecka. 2008. "Fluoride in dentistry and dental restoratives," in A. Tressaud, and G. Haufe eds. Fluorine and Health. Amsterdam, NL; Boston, MA: Elsevier. ISBN 9780444530868.

- Rovere, Richard H. 1959. Senator Joe McCarthy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520204727.

- Taricska, J.R., L.K. Wang, Y.T. Hung, and K.H. Li. 2006. "Fluoridation and defluoridation," in L.K. Wang, Y.T. Hung, and N.K. Shammas eds. 2006. Advanced Physicochemical Treatment Processes, Handbook of Environmental Engineering 4. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. ISBN 9781597450294.

- The British Fluoridation Society. 2004. "The extent of water fluoridation," in One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation, 2nd ed. Manchester, UK: British Fluoridation Society. ISBN 095476840X.

- United States. Public Health Service. Committee to Coordinate Environmental Health and Related Programs. Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Fluoride. 1991. Review Of Fluoride: Benefits And Risks. Report Of The Ad Hoc Subcommittee On Fluoride. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, Dept. of Health and Human Services.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Fluoride Action Network.

- Interview with Christopher Bryson, from Democracy Now!', June 17, 2004.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.