Toni Morrison

| Toni Morrison | |

|---|---|

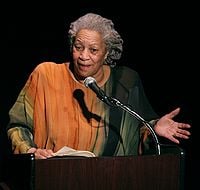

Toni Morrison in 2008 | |

| Born | February 18 1931 Ohio, United States |

| Died | August 5 2019 (aged 88) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, editor |

| Genres | African American literature |

| Notable work(s) | Beloved, Song of Solomon, The Bluest Eye |

| Notable award(s) | Pulitzer Prize for Fiction 1988 Nobel Prize in Literature 1993 Presidential Medal of Freedom 2012 |

| Influences | James Baldwin, William Faulkner, Doris Lessing, Herman Melville |

| Influenced | bell hooks , Octavia Butler |

| Signature |

|

Toni Morrison (February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019), was a Nobel Prize-winning American author, editor, and professor. Morrison helped promote Black literature and authors when she worked as an editor for Random House in the 1960s and 1970s, where she edited books by authors including Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones. Morrison herself would later emerge as one of the most important African American writers of the twentieth century.

Her novels are known for their epic themes, vivid dialogue, and richly detailed black characters; among the best known are her novels The Bluest Eye, published in 1970, Song of Solomon, and Beloved, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1988. This story describes a slave who found freedom but killed her infant daughter to save her from a life of slavery.

Morrison is the first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2001 she was named one of the "30 Most Powerful Women in America" by Ladies' Home Journal.

Early life and career

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford in Lorain, Ohio, the second of four children in a working-class family.[1] As a child, Morrison read constantly; among her favorite authors were Jane Austen and Leo Tolstoy. Morrison's father, George Wofford, a welder by trade, told her numerous folktales of the Black community (a method of storytelling that would later work its way into Morrison's writings).

In 1949 Morrison entered Howard University to study English. While there she began going by the nickname of "Toni," which derives from her middle name, Anthony.[1][2] Morrison received a B.A. in English from Howard University in 1953, then earned a Master of Arts degree, also in English, from Cornell University in 1955, for which she wrote a thesis on suicide in the works of William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf.[3] After graduation, Morrison became an English instructor at Texas Southern University in Houston, Texas (from 1955-1957) then returned to Howard to teach English. She became a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.

In 1958 she married Harold Morrison. They had two children, Harold and Slade, but divorced in 1964. After the divorce she moved to Syracuse, New York, where she worked as a textbook editor. Eighteen months later she went to work as an editor at the New York City headquarters of Random House.[3]

As an editor, Morrison played an important role in bringing African American literature into the mainstream. She edited books by such Black authors as Toni Cade Bambara, Angela Davis and Gayl Jones.

Writing career

Morrison began writing fiction as part of an informal group of poets and writers at Howard University who met to discuss their work. She went to one meeting with a short story about a black girl who longed to have blue eyes. The story later evolved into her first novel, The Bluest Eye (1970), which she wrote while raising two children and teaching at Howard.[3]In 2000 it was chosen as a selection for Oprah's Book Club.[4]

In 1973 her novel Sula was nominated for the National Book Award. Her third novel, Song of Solomon (1977), brought her national attention. The book was a main selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club, the first novel by a Black writer to be so chosen since Richard Wright's Native Son in 1940. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Beloved

Her novel, Beloved, won the 1987 Pulitzer Prize. The novel is loosely based on the life and legal case of the slave Margaret Garner, about whom Morrison later wrote in the opera Margaret Garner (2005). The Book's Epigraph says: "Sixty Million and more." Morrison is referring to the estimated number of slaves who died in the slave trade. More specifically, she is referring to the Middle Passage.

A survey of eminent authors and critics conducted by The New York Times found Beloved the best work of American fiction of the past 25 years; it garnered 15 of 125 votes, finishing ahead of Don DeLillo's Underworld (11 votes), Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian (8) and John Updike's Rabbit series (8).[5] The results appeared in The New York Times Book Review on May 21, 2006.[6]

TIME Magazine included the novel in its TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[7]

When the novel failed to win the National Book Award as well as the National Book Critics Circle Award, a number of writers protested the omission.[3][8] Beloved was adapted into the 1998 film of the same name starring Oprah Winfrey and Danny Glover. Morrison later used Margaret Garner's life story again in an opera, Margaret Garner, with music by Richard Danielpour.

Later life

Morrison taught English at two branches of the State University of New York. In 1984 she was appointed to an Albert Schweitzer chair at the University at Albany, The State University of New York. From 1989 until her retirement in 2006, Morrison held the Robert F. Goheen Chair in the Humanities at Princeton University.

Though based in the Creative Writing Program, Morrison did not regularly offer writing workshops to students after the late 1990s, a fact that earned her some criticism. Rather, she conceived and developed the prestigious Princeton Atelier, a program that brings together talented students with critically acclaimed, world-famous artists. Together the students and the artists produce works of art that are presented to the public after a semester of collaboration. In her position at Princeton, Morrison used her insights to encourage not merely new and emerging writers, but artists working to develop new forms of art through interdisciplinary play and cooperation.

In 1993 Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Black woman to win the award.[2] Her citation reads: Toni Morrison, "who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality." Shortly afterwards, a fire destroyed her Rockland County, New York home.[1][9]

In November 2006, Morrison visited the Louvre Museum in Paris as the second in its Grand Invité program to guest-curate a month-long series of events across the arts on the theme of "The Foreigner's Home."

In May 2010, Morrison appeared at PEN World Voices for a conversation with Marlene van Niekerk and Kwame Anthony Appiah about South African literature, and specifically van Niekerk's 2004 novel Agaat.

Morrison wrote books for children with her younger son, Slade Morrison, who was a painter and a musician. Slade died of pancreatic cancer on December 22, 2010, aged 45.[10] Morrison's novel Home was half-completed when her son died.

Morrison had stopped working on her latest novel when her son died. She said that afterward, "I stopped writing until I began to think, He would be really put out if he thought that he had caused me to stop. 'Please, Mom, I'm dead, could you keep going ...?'"[11]

She completed Home and dedicated it to her son Slade Morrison.[12] Published in 2012, it is the story of a Korean War veteran in the segregated United States of the 1950s, who tries to save his sister from brutal medical experiments at the hands of a white doctor.[11]

Morrison debuted another work in 2011: She worked with opera director Peter Sellars and Malian singer-songwriter Rokia Traoré on a new production, Desdemona, taking a fresh look at William Shakespeare's tragedy Othello. The trio focused on the relationship between Othello's wife Desdemona and her African nursemaid, Barbary, who is only briefly referenced in Shakespeare. The play, a mix of words, music and song, premiered in Vienna in 2011.[13]

In August 2012, Oberlin College became the home base of the Toni Morrison Society,[14] an international literary society founded in 1983, dedicated to scholarly research of Morrison's work.[15]

Morrison's eleventh novel, God Help the Child, was published in 2015. It follows Bride, an executive in the fashion and beauty industry whose mother tormented her as a child for being dark-skinned – a childhood trauma that has dogged Bride her whole life.[16]

Morrison died at Montefiore Medical Center in The Bronx, New York City on August 5, 2019, from complications of pneumonia. She was 88 years old.

Legacy

Toni Morrison is one of a number of significant African-American writers who conveyed the experience of post-slavery, post-segregation blacks. She helped promote Black literature and authors when she worked as an editor for Random House in the 1960s and 1970s, later emerging herself as one of the most important African American writers of the twentieth century.

Although her novels typically concentrate on black women, Morrison did not identify her works as feminist. She stated that "it's off-putting to some readers, who may feel that I'm involved in writing some kind of feminist tract. I don't subscribe to patriarchy, and I don't think it should be substituted with matriarchy. I think it's a question of equitable access, and opening doors to all sorts of things."[17]

The Toni Morrison Papers are part of the permanent library collections of Princeton University|, where they are held in the Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, includes writing by Morrison.[18] Visitors can see her quote after they have walked through the section commemorating individual victims of lynching.

Morrison was the subject of a film titled Imagine — Toni Morrison Remembers, directed by Jill Nicholls and shown on BBC One television on July 15, 2015, in which Morrison talked to Alan Yentob about her life and work.

Awards and Honors

At its 1979 commencement ceremonies, Barnard College awarded her its highest honor, the Barnard Medal of Distinction. Oxford University awarded her an honorary Doctor of Letters degree in June 2005.

She was nominated for a Grammy Award in 2008 for Best Spoken Word Album for Children for Who's Got Game? The Ant or the Grasshopper? The Lion or the Mouse? Poppy or the Snake?

In May 2011, Morrison received an Honorable Doctor of Letters Degree from Rutgers University during commencement where she delivered a speech of the "pursuit of life, liberty, meaningfulness, integrity, and truth."

In March 2012, Morrison established a residency at Oberlin College. On May 29, 2012, President Barack Obama presented Morrison with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

She won the Pulitzer Prize in 1988 for Beloved and the Nobel Prize in 1993. In May 2012, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 2016, she received the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction.

Works

Novels

- The Bluest Eye (1970 ISBN 0452287065)

- Sula (1974 ISBN 1400033438)

- Song of Solomon (1977 ISBN 140003342X)

- Tar Baby (1981 ISBN 1400033446)

- Beloved (1987 ISBN 1400033411)

- Jazz (1992 ISBN 1400076218)

- Paradise (1999 ISBN 0679433740)

- Love (2003 ISBN 0375409440)

- A Mercy (2008 ISBN 0307264238)

- Home (2012 ISBN 0307594165)

- God Help the Child (2015 ISBN 0307594173)

Children's literature (with Slade Morrison)

- The Big Box (2002)

- The Book of Mean People (2002)

Short stories

- "Recitatif" (1983)

Plays

- Dreaming Emmett (performed 1986)

Libretti

- Margaret Garner (first performed May 2005)

Non-fiction

- The Black Book (1974)

- Birth of a Nation'hood (co-editor) (1997)

- Playing in the Dark (1992)

- Remember:The Journey to School Integration (April 2004)

Articles

- "This Amazing, Troubling Book" (An analysis of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Claudia Dreifus, "CHLOE WOFFORD Talks about TONI MORRISON." The New York Times, September 11, 1994.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rome Neal, "Toni Morrison: Words Of Love" CBS News, April 4, 2004.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 William Grimes, "Toni Morrison Is '93 Winner Of Nobel Prize in Literature" The New York Times, October 8, 1993. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ "The Bluest Eye" Oprah's Book Club. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ A. O. Scott, In Search of the Best - New York Times Sunday book review. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ What Is the Best Work of American Fiction of the Last 25 Years?, The New York Times May 21, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Lev Grossman, Beloved - ALL-TIME 100 Novels TIME, January 6, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Louis Menand, "All That Glitters - Literature's global economy" The New Yorker, December 18, 2005. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ "New York Home of Toni Morrison Burns." The New York Times, December 26, 1993. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ About the Artist Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Christopher Bollen, Toni Morrison's Haunting Resonance Interview, May 1, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Bob Minzesheimer, "New novel 'Home' brings Toni Morrison back to Ohio" USA Today, May 7, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Elaine Sciolino, Toni Morrison's 'Desdemona' talks back to 'Othello' The New York Times, October 25, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ "Society History", The Toni Morrison Society. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ "Toni Morrison Society Celebrates 20 Years", Oberlin College, September 18, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Roxanne Gay, God Help the Child by Toni Morrison review – 'incredibly powerful' The Guardian, April 29, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Isheka N. Harrison, In Her Own Words: Tony Morrison on White Supremacy and White Feminism The Moguldom Nation, August 6, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ The National Memorial for Peace and Justice Retrieved August 24, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bloom, Harold, Toni Morrison. Chelsea House, 2000. ISBN 9780791052587

- McKay, Kellie. Y, Critical Essays on Toni Morrison. G.K. Hall, 1988. ISBN 9780816188840

- Samuels, Wilfred D, and Clenora Hudson-Weeks. Toni Morrison. Twayne Publishers, 1990. ISBN 9780805776010

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

|

1976: Saul Bellow | 1977: Vicente Aleixandre | 1978: Isaac Bashevis Singer | 1979: Odysseas Elytis | 1980: Czesław Miłosz | 1981: Elias Canetti | 1982: Gabriel García Márquez | 1983: William Golding | 1984: Jaroslav Seifert | 1985: Claude Simon | 1986: Wole Soyinka | 1987: Joseph Brodsky | 1988: Naguib Mahfouz | 1989: Camilo José Cela | 1990: Octavio Paz | 1991: Nadine Gordimer | 1992: Derek Walcott | 1993: Toni Morrison | 1994: Kenzaburo Oe | 1995: Seamus Heaney | 1996: Wisława Szymborska | 1997: Dario Fo | 1998: José Saramago | 1999: Günter Grass | 2000: Gao Xingjian |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.