Tongmenghui

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

The Tongmenghui (Chinese: 同盟會; Pinyin: Tóngménghuì; Wade-Giles: T'ung-meng Hui; lit. United Allegiance Society), also known as the Chinese United League or the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, was a secret society and underground resistance movement organized by Sun Yat-sen and Song Jiaoren in Tokyo, Japan, on August 20, 1905. This new alliance was created through the unification of Sun's Xingzhonghui, or Revive China Society, the Guangfuhui, or Restoration Society, and other Chinese revolutionary groups.

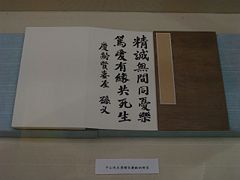

Combining republican, nationalist, and socialist objectives, the Tongmenghui's political platform was "to overthrow the Manchu empire and to restore China to the Chinese, to establish a republic, and to distribute land equally among the people." (Chinese: 驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權) Among the Allegiance's members was Li Zongren, prominent Guangxi warlord and Kuomintang military commander and Wang Jingwei, who would later serve as the collaborationist President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government in Japanese occupied China during World War II. In 1906, a branch was formed in Singapore, following Sun's visit there; this was called the Nanyang branch and served as headquarters of the organization for Southeast Asia. After the establishment of the Republic of China, the Tongmenghui formed, in August 1912, the nucleus of the Kuomintang, which translates to Nationalist Party.

Background

The last days of the Qing Dynasty were marked by civil unrest and foreign invasions. Various internal rebellions caused the deaths of millions of people, and conflicts with foreign powers almost always resulted in humiliating unequal treaties that demanded large sums in reparation and compromised territorial integrity. In addition, there were feelings that political power should return to the majority Han Chinese from the minority Manchus. Responding to these civil failures and discontent, the Qing Imperial Court attempted various reforms,such as the decision to draft a constitution in 1906, the establishment of provincial legislatures in 1909, and the preparation for a national parliament in 1910. Many of these measures were steadfastly opposed by the conservatives of the Qing Court, and many reformers were either imprisoned or executed. The failures of the Imperial Court to enact such reforming measures of political liberalization and modernization caused the reformists to steer toward the road of revolution.

As a teen, Sun Yat Sen had lived with his elder brother in Hawaii. He converted to Christianity and studied medicine at the Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the medical missionary John G. Kerr. In 1892, he earned a license to practice as a medical doctor from the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of The University of Hong Kong), of which he was one of the first two graduates. He practiced medicine in that city briefly in 1893. Growing increasingly troubled by the conservative Qing government and its refusal to adopt knowledge from the more technologically advanced Western nations, Dr. Sun quit his medical practice in order to devote his time to transforming China. At first, Sun aligned himself with the reformists Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao who sought to transform China into a Western-style constitutional monarchy. In 1894, Sun wrote a long letter to Li Hongzhang, the governor-general of Zhili and a reformer in the court, with suggestions on how to strengthen China, but he was rebuffed. Since Sun had not had a traditional education in the Confucian classics, the gentry did not accept Sun into their circles. From then on, Sun began to call for the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic.

Sun went to Hawaii and, on November 24, 1894, founded the Xingzhonghui (Chinese: 興中會; pinyin: Xīngzhōnghuì), translated as the Revive China Society or the Society for Regenerating China]] forward the goal of establishing prosperity for China and as a platform for future revolutionary activities. Members were mainly fellow Cantonese expatriates and from the lower social classes. Those admitted to the society swore the following oath:

- Expel the foreigners, revive China, and establish a unified government. (驅逐韃虜,恢復中華,建立合眾政府)

Tongmenghui

After a failed coup in 1895, Sun spent 16 years in exile in Europe, the United States, Canada, and Japan, raising money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. In Japan, where he was known as Nakayama Shō (Kanji: 中山樵, The Woodcutter of Middle Mountain), he joined dissident Chinese groups and soon became their leader. On August 20, 1905, together with Song Jiaoren, he organized the Tongmenghui (Chinese: 同盟會; Pinyin: Tóngménghuì; Wade-Giles: T'ung-meng Hui; lit. United Allegiance Society), also known as the Chinese United League or the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, was a secret society and underground resistance movement uniting Sun's Xingzhonghui, (Revive China Society); the Guāngfùhuì (光復會 "Revive the Light Society," or Restoration Society), an anti-Qing Empire organization established by Cai Yuanpei in 1904; and other Chinese revolutionary groups. Their members were mostly Chinese revolutionaries who had fled to Japan or had gone there to study. Sun’s deputy was Huang Xing, a popular leader of the Chinese revolutionary movement in Japan. Sun also had supporters among the Japanese, such as Miyazaki Toten, who introduced him to Tsuyoshi Inukai and other key Japanese politicians, paving the way for Sun to operate from Japan. Sun Yat Sen openly advocated military activism to overthrow the Qing Dynasty and establish a Chinese republic. Combining republican, nationalist, and socialist objectives, the Tongmenghui's political platform was "to overthrow the Manchu empire and to restore China to the Chinese, to establish a republic, and to distribute land equally among the people." (Chinese: 驅除韃虜,恢復中華,創立民國,平均地權) Among the Allegiance's members was Li Zongren, prominent Guangxi warlord and Kuomintang military commander and Wang Jingwei, who would later serve as the collaborationist President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government in Japanese occupied China during World War II.

The movement, generously supported by overseas Chinese funds, also gained political support from regional military officers and some of the reformers who had fled China after the Hundred Days' Reform. Tiandihui, a powerful Chinese secret society into which Sun had been inducted in Hawaii, provided much of Sun's funding.

In Japan, Sun also met and befriended Mariano Ponce, then a diplomat of the First Philippine Republic. Sun also supported the cause for Philippine Independence.

Singapore

Sun made a total of eight visits to Singapore between 1900 and 1911. His first visit on September 7, 1900, was to rescue his friend and supporter Miyazaki Toten, who had been arrested there, an action which resulted in his own arrest and his banishment from the island for five years. During his next visit in June 1905, he met local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock, Tan Chor Nam and Lim Nee Soon in a meeting which was to mark the commencement of direct support from the Nanyang Chinese. Upon hearing their reports of overseas Chinese revolutionists organizing themselves in Europe and Japan, he urged them to establish a Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui, which came officially into being on April 6, 1906, during his next visit.

The chapter was housed in a villa known as Wan Qing Yuan (晚晴園) and donated for the use of revolutionalists by Teo. In 1906, the chapter grew in membership to 400, and in 1908, when Sun was in Singapore to escape the Qing government in the wake of the failed Zhennanguan Uprising, the chapter had become the regional headquarters for Tongmenghui branches in Southeast Asia. Sun and his followers traveled from Singapore to Malaya and Indonesia to spread their revolutionary message. By this time the Tongmenghui already had over twenty branches with over 3,000 members around the world.

Revolution of 1911

By 1911, the Tongmenghui had over 10,000 members, many of whom had been students in Japan and had returned to China to continue their activities in secret. Many young Chinese women joined the alliance and defied tradition by seeking a higher education and refusing to bind their feet. Some were soldiers or officers in the Chinese New Army, or members of the new provincial assemblies. Their activities resulted in at least seven uprisings against the Qing dynasty. [1]

On October 10, 1911, some military units in Wuchang under the influence of the Tongmenghui rose in revolt. The revolt quickly spread to neighboring cities, and Tongmenghui members throughout the country rose in immediate support of the Wuchang revolutionary forces. On October 12, the Revolutionaries succeeded in capturing Hankou and Hanyang. The action quickly spread to other areas south of the Yangtze River, and revolutionaries established a provisional government in Nanjing. A month later, Sun Yat-sen returned to China from the United States, where he had been raising funds among overseas Chinese and American sympathizers. On January 1, 1912, delegates from the independent provinces elected Sun Yat-sen as the first Provisional President of the Republic of China. Leaders of the Tongmenghui played a prominent role in establishing the Provisional Republican Government. After the abdication of the Qing emperor on February 12, 1912, several other political parties merged with the Tongmenghui to form the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang), the precursor of the Chinese Nationalist Party.

Legacy

The Tongmenghui successfully combined several smaller revolutionary groups into one cohesive party, which was better able to promote their shared ideals. It established an organized operation and encouraged the development of many any leaders who later occupied prominent positions in the Republican government. The Tongmenghui kept the spirit of revolution alive, even after a series of failed uprisings.

Sun's foresight in tapping into the resources of the overseas Chinese population was essential to the eventual success of revolutionary efforts. Sun sold bonds to the supporters of the regime he planned to establish in China, promising a tenfold return on the purchase price when that goal was achieved. The role that overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia played during the 1911 Revolution was so significant that Sun himself recognized "Overseas Chinese as the Mother of the Revolution." In one particular instance, his personal plea for financial aid at the Penang Conference held on November 13, 1910 in Malaya, helped launch a major drive for donations across the Malay Peninsula, an effort which helped finance the Second Guangzhou Uprising (also commonly known as the Yellow Flower Mound revolt) in 1911.

The platform of the Tongmenghui, Sun’s Three Principles of the People, was claimed as the basis for the ideologies of the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek, of the Communist Party of China under Mao Zedong, and of the Wang Jingwei Government.

See also

- Kuomintang

- History of the Republic of China

Notes

- ↑ Dorothy Perkins. 1999. Encyclopedia of China the essential reference to China, its history and culture. New York: Facts on File. 431.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Sun, Yat-sen, and Frank W. Price. 1981. The three principles of the people. Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China: China Cultural Service.

- Schiffrin, Harold Z. 1980. Sun Yat-sen, reluctant revolutionary. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316773395 ISBN 9780316773393

- Schiffrin, Harold Z. 1968. Sun Yat-sen and the origins of the Chinese revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wright, Mary (Clabaugh). 1968. China in revolution The First Phase, 1900-1913. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Perkins, Dorothy. 1999. Encyclopedia of China the essential reference to China, its history and culture. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816026939 ISBN 9780816026937

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tongmenghui history

- Revive_China_Society history

- Sun_Yat-sen history

- History_of_the_Republic_of_China history

- Kuomintang history

- Guangfuhui history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.