Theseus

Theseus (Greek Θησεύς) was a legendary king of Athens and son of Aethra and either Aegeus or Poseidon, as his mother had laid with both in the same night. Much like Perseus, Cadmus, and Heracles, Theseus was a founder-hero whose exploits represented the triumph of Athenian mores and values over archaic and barbarous belief. As Heracles represented the pinnacle of Dorian society, Theseus was an idol for the Ionians and was considered by Athenians to be their own great founder and reformer. In mythological accounts, he was credited with the synoikismos ("dwelling together")—the political unification of Attica under Athens, which was metaphorically represented in the tales of his mythic labors. This understanding is even attested to in the etymology of his name, which is derived from the same root as θεσμός ("thesmos"), Greek for institution. Because he was the unifying king, Theseus was credited with constructing and dwelling in a palace on the fortress of the Acropolis, which may have been similar to the palace excavated in Mycenae.

In addition to his mythological importance, Theseus was also a relevant figure in Hellenic religious life. For instance, Pausanias reports that after the synoikismos, Theseus established a cult of Aphrodite Pandemos ("Aphrodite of all the People") and Peitho on the southern slope of the Akropolis.

Mythological accounts

Birth and youthful adventures of Theseus

The story of Theseus properly begins with the account of his semi-miraculous conception. In it, his mother, Aethra, a princess of Troezen (a small city southwest of Athens), is romanced by Aegeus, one of the primordial kings of the Greek capital. After laying with her husband on their wedding night, the new queen felt compelled to walk down to the seashore, where she waded out to the nearby island of Sphairia, encountered Poseidon (god of the sea and of earthquakes), and had intercourse with him (either willingly or otherwise).

In the pre-scientific understanding of procreation, the mixture of semen that resulted from this two-part union gave Theseus a combination of divine as well as mortal characteristics in his nature; such double fatherhood, one father immortal, one mortal, was a familiar feature among many Greek heroes.[1] When Aethra became pregnant, Aegeus decided to return to Athens. Before leaving, however, he buried his sandals and sword under a huge rock and told her that when their son grew up, he should demonstrate his heroic virtues by moving the stone and claiming his royal legacy.

Upon returning to his own kingdom, Aegeus was joined by Medea, who had fled Corinth after slaughtering the children she had borne Jason. Her beauty convinced the king to take her as a royal consort.

Meanwhile, Theseus was raised in the land of his mother. When the young hero reached young adulthood, he was easily able to displace the rock and recover his father's arms. Seeing him return with these symbolic items, his mother then told him the truth about his father's identity and suggested that he must take the weapons back to the king and claim his birthright. To get to Athens, Theseus could choose to go by sea (which was the safe route) or by land, following a dangerous path around the Saronic Gulf, where he would encounter a string of six entrances to the Underworld, each guarded by chthonic enemies in the forms of thieves and bandits. Young, brave, and ambitious, Theseus decided to follow the land route, and defeated a great many bandits along the way.

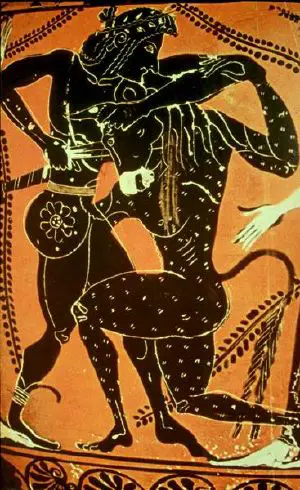

- At the first site, which was Epidaurus, sacred to Apollo and the healer Aesculapius, Theseus turned the tables on the chthonic bandit, Periphetes (the "clubber"), by stealing his weapon and using it against him. This stout staff eventually became an emblem of the hero, such that it often identifies him in vase-paintings.

- At the Isthmian entrance to the Netherworld, he encountered a robber named Siris—a grim malefactor who enjoyed capturing travelers, tying them between two pine trees that were bent down to the ground, and then letting the trees go, tearing his victims apart. After besting the monstrous villain in combat, Theseus dispatched him by his own method. He then raped Siris' daughter, Perigune, fathering the child Melanippus.

- In another deed north of Isthmus, at a place called Crommyon, he killed an enormous pig, the Crommyonian sow, bred by an old crone named Phaea. Some versions name the sow herself as Phaea.

- Near Megara, Theseus came across an elderly robber named Sciron, who preyed upon travelers that pitied him for his advanced age. Specifically, he waited near a particularly narrow pathway on the cliff and asked passersby to wash his feet. When they knelt down to accommodate him, the villain kicked them off the cliff behind them, where they were eaten by a sea monster (or, in some versions, a giant turtle). In his typically retaliatory manner, Theseus pushed him off the cliff.

- Later, the hero confronted Cercyon, king of Eleusis, who challenged travelers to a wrestling match and, when he had beaten them, killed them. As can be anticipated, Theseus proceeded to defeat Cercyon, after which point he slaughtered him. (In interpretations of the story that follow the formulas of Frazer's The Golden Bough, Cercyon was a "year-King," who was required to do annual battle for his life, for the good of his kingdom, and was succeeded by the victor. Theseus overturned this archaic religious rite by refusing to be sacrificed.)

- The last bandit that the young hero-king encountered was Procrustes, who dwelt in the plains of Eleusis. A seemingly harmless hotelier, this final brigand offered weary travelers the chance to rest in his bed. Unfortunately for those who accepted his hospitality, he then forced them to fit the beds precisely, either by stretching them or by cutting off their feet. Once again, Theseus turned the tables on Procrustes, although it is not said whether he cut Procrustes to size or stretched him to fit.[2]

Each of these sites was a very sacred place already of great antiquity when the deeds of Theseus were first attested in painted ceramics, which predate the literary texts.[3]

Medea and the Marathonian Bull

When Theseus arrived at Athens, he did not reveal his true identity immediately. Aegeus gave him hospitality but was suspicious of the young, powerful stranger's intentions. Aegeus' wife Medea recognized Theseus immediately as Aegeus' son and worried that Theseus would be chosen as heir to Aegeus' kingdom instead of her son, Medus. She tried to arrange to have Theseus killed by asking him to capture the Marathonian Bull, an emblem of Cretan power.

On the way to Marathon, Theseus took shelter from a storm in the hut of an ancient woman named Hecale. She swore to make a sacrifice to Zeus if Theseus was successful in capturing the bull. Theseus did capture the bull, but when he returned to Hecale's hut, she was dead. In her honor. Theseus gave her name to one of the demes of Attica, making its inhabitants in a sense her adopted children.

When Theseus returned victorious to Athens, where he sacrificed the Bull, Medea tried to poison him. At the last second, Aegeus recognized the sandals, shield, and sword, and knocked the poisoned wine cup from Theseus's hand. Thus, father and son were reunited.[4]

Minotaur

Unfortunately, the political situation in the prince's new domain was suboptimal. The Athenians, after a disastrous war with King Minos of Crete, had been forced to agree to a grim series of tributes: Every nine years, seven Athenian boys and seven Athenian girls were to be sent to Crete to be devoured by the Minotaur (a foul human/bovine hybrid that dwelt in the king's labyrinth).

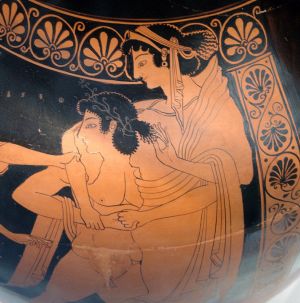

On one of these fell occasions, Theseus volunteered to take the place of one of the youths in order to slay the monster. Their boat set off to Crete sporting a black sail, with Theseus promising his father that, if successful, he would replace it with a white sail before he returned. Once in Crete, Theseus made a very favorable impression on King Minos' daughter Ariadne, who instantly fell in love with the handsome youth. Her intense feelings compelled her to offer the hero a precious family heirloom: A magical ball of string that would lead him out of the maze after his encounter with the beast.

After a titanic battle, Theseus successful dispatched the foul creature and managed to escape the island with all of the children (and Ariadne) in tow. However, the young hero's fickle heart caused him to lose interest in the princess, and he abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos. Originally optimistic that her prince would return, Ariadne eventually realized that Theseus had only used her and she cursed him, causing him to forget to change the black sail to white.

When Theseus and the youths returned to the city, there was much rejoicing, save by the heartsick king. Indeed, the worried monarch had been seated on a watchtower waiting for any sign of Theseus' return and, seeing the black sail, became convinced of his precious son's death and committed suicide by throwing himself into the sea (thereafter named the Aegean).[5]

Ship of Theseus

As an aside, some accounts describe the ship of Theseus being kept in service for many years after his return to Athens. However, as wood wore out or rotted, it was replaced until it was unclear how much of the original ship actually remained. Philosophical questions about the nature of identity in circumstances like this are sometimes referred to as a Ship of Theseus Paradox.

Pirithous

Theseus' best friend was Pirithous, prince of the Lapiths, a powerful and headstrong youth that he first encountered in a hostile physical confrontation. The circumstances of their initial meeting transpired as follows.

In his travels, Pirithous had heard various tales of the Athenian hero's physical prowess but remained unconvinced. Desiring proof, he decided to purposefully provoke Theseus by rustling his herd of cattle. When the hero noticed that his prized animals were gone, he set out in pursuit.

When Theseus finally caught up to the villainous thief, he challenged him to battle, and the two fell into a frenzy of attacks, parries, feints, and counter-feints. After several minutes of indecisive combat, the two were so impressed with each other they took an oath of mutual friendship. In order to cement this union, they decided to hunt for the Calydonian Boar.

In Iliad I, Nestor numbers Pirithous and Theseus "of heroic fame" among an earlier generation of heroes of his youth, "the strongest men that Earth has bred, the strongest men against the strongest enemies, a savage mountain-dwelling tribe whom they utterly destroyed." No trace of such an oral tradition, which Homer's listeners would have recognized in Nestor's allusion, survived in literary epic.[6]

Theseus and Pirithous

Since Theseus, already a great abductor of women, and his bosom companion, Pirithous, were both sons of Olympians (Poseidon and Zeus, respectively), they pledged that they would both marry daughters of Zeus.[7] Theseus, in an old tradition, chose Helen of Troy, and together they kidnapped her, intending to keep her until she was old enough to marry. More dangerously, Pirithous chose Persephone (the bride of Hades). They left Helen with Theseus's mother, Aethra at Aphidna, whence she was rescued by the Dioscuri.

On Perithous' behalf, the pair traveled to the underworld. Hades pretended to offer them hospitality and laid out a feast, but as soon as the two visitors sat down, snakes coiled around their feet and held them fast. In some versions, the stone itself grew and attached itself to their thighs.

When Heracles came into Hades for his twelfth task, he freed Theseus but the earth shook when he attempted to liberate Pirithous, and Pirithous had to remain in Hades for eternity. When Theseus returned to Athens, he found that the Dioscuri had taken Helen and Aethra back to Sparta. When Heracles had pulled Theseus from the chair where he was trapped, some of his thigh stuck to it; this explains the supposedly lean thighs of Athenians.[8]

Phaedra and Hippolytus

Phaedra, Theseus's first wife, bore Theseus two sons, Demophon and Acamas. While these two were still in their infancy, Phaedra fell in love with Hippolytus, Theseus's son by Antiope. According to some versions of the story, Hippolytus had scorned Aphrodite to become a devotee of Artemis, so Aphrodite made Phaedra fall in love with him as punishment. He rejected her out of chastity. Alternatively, in Euripides' version, Hippolytus, Phaedra's nurse told Hippolytus of her mistress's love and he swore he would not reveal the nurse as his source of information. To ensure that she would die with dignity, Phaedra wrote to Theseus on a tablet claiming that Hippolytus had raped her before hanging herself. Theseus believed her and used one of the three wishes he had received from Poseidon against his own son. The curse caused Hippolytus's horses to be frightened by a sea monster (usually a bull), which caused the youth to be dragged to his death. Artemis would later tell Theseus the truth, promising to avenge her loyal follower on another follower of Aphrodite. In a third version, after Phaedra told Theseus that Hippolytus had raped her, Theseus killed his son himself, and Phaedra committed suicide out of guilt, for she had not intended for Hippolytus to die. In yet another version, Phaedra simply told Theseus Hippolytus had raped her and did not kill herself, and Dionysus sent a wild bull which terrified Hippolytus's horses.

A cult grew up around Hippolytus, associated with the cult of Aphrodite. Girls who were about to be married offered locks of their hair to him. The cult believed that Asclepius had resurrected Hippolytus and that he lived in a sacred forest near Aricia in Latium.

Death

Though many earlier sources lack an account of the hero's demise, later versions describe a gradual decline in his power and influence. In the end, he is thought to died during a diplomatic mission to the kingdom of Skyros, where the reigning monarch unexpectedly pushed him from a cliff during a seemingly peaceful walk. In the various surviving sources, different motives are assigned to the king's murderous act, though it is often cited as a visceral response to the hero's larger-than-life reputation or as an attempt to curry favor with other powerful monarchs in the area.[9]

Theseus in classical poetry and drama

In The Frogs, Aristophanes credited him with inventing many everyday Athenian traditions. If the theory of a Minoan hegemony (Minoan cultural dominance is reflected in the ceramic history, but not necessarily political dominance) is correct, he may have been based on Athens' liberation from this political order rather than on a historical individual.

In Plutarch's vita of Theseus, he makes use of varying accounts of the death of the Minotaur, Theseus' escape, and the love of Ariadne for Theseus. Plutarch's sources, not all of whose texts have survived independently, included Pherecydes (mid-sixth century), Demon (c. 300), Philochorus and Cleidemus (both fourth century).[10]

Theseus in Hellenistic religion

Though the topic has prompted some debate,[11] it appears that the cult of Theseus played an important role in Hellenistic religiosity. While the ancient Greeks did distinguish between heroes and gods (with the former category referring to deceased humans), this did not enjoin them from constructing shrines and temples to these former worthies. Theseus, as the founding hero of the Athenian deme, received particular attention, with an impressive heroa (hero temple) dedicated to him and containing his purported remains.[12]

In addition to these architectural commemorations, Theseus was also an important figure in Athenian popular religion, as he was honored with public sacrifices "on the eight day of every month" (in ceremonies shared with his divine sire Poseidon) and celebrated in an extensive annual festival (the Thesia).[13] These ceremonies, many of which far predated the mythic accounts of the hero, were nonetheless reinterpreted to commemorate him, with etiological explanations for various archaic practices being derived from aspects of Theseus' life story.[14] Parke suggests that the hero's posthumous influence can possibly be tied to "a popular belief that Theseus when alive had been a friend of the people and had established a democratic government in his combined state of Athens."[15]

Notes

- ↑ Descriprion of Greece x.6.1.

- ↑ Powell, 324-327.

- ↑ Gantz, 249-255.

- ↑ B. B. Shefton, "Medea at Marathon," American Journal of Archaeology 60:2 (April 1956), 159-163.

- ↑ Powell, 357-360.

- ↑ Gantz, 278-280.

- ↑ Kerenyi, 237.

- ↑ Gantz, 291-295.

- ↑ Gantz, 297-298.

- ↑ Edmund P. Cueva, "Plutarch's Ariadne in Chariton's Chaereas and Callirhoe," American Journal of Philology 117:3 (Fall 1996), 473-484.

- ↑ C.H. Weller, "May a Hero Have a Temple?" Classical Philology 12:1 (January 1917), 96-97.

- ↑ Mikalson, 40.

- ↑ Mikalson, 40-41.

- ↑ Parke, 77-80.

- ↑ Parke, 81-82.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Apollodorus. Gods & Heroes of the Greeks. Translated by Michael Simpson. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977. ISBN 0870232053

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Translated by John Raffan. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985. ISBN 0631112413

- Dillon, Matthew. Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece. London: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415127750

- Farnell, Lewis Richard. The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907.

- Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ISBN 080184410X

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0140171991

- Harrison, Jane Ellen. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1908.

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. London: Thames and Hudson, 1951. ISBN 0500270481

- Mikalson, Jon D. Ancient Greek Religion. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0631232222

- Parke, H.W. Festivals of the Athenians. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. ISBN 0801410541

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0137167148

- Plutarch. Theseus. Translated by John Dryden. Accessed online at the Internet Classics Archive. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Rose, H.J. A Handbook of Greek Mythology. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0525470417

- Ruck, Carl A.P. and Danny Staples. "Theseus: Making the New Athens." In The World of Classical Myth: Gods and Goddesses, Heroines and Heroes. Carolina Academic Press: 1994. ISBN 0890895759

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.