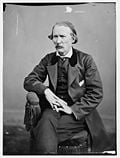

John C. Fremont

| John Charles Frémont | |

| |

| In office 1847 â 1847 | |

| Succeeded by | Robert F. Stockton |

|---|---|

Senior Senator, California

| |

| In office September 9, 1850 â March 3, 1851 | |

| Succeeded by | John B. Weller |

| Born | |

| Political party | Democrat, Republican |

| Spouse | Jessie Benton Frémont |

| Profession | Politician |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

John Charles FrĂ©mont (January 21, 1813 â July 13, 1890), was an American military officer and explorer. Fremont mapped most of the Oregon Trail and climbed the second highest peak in the Wind River Mountains. During the 1840s, that era's penny press accorded FrĂ©mont the epithet "The Pathfinder," which remains in use, sometimes as "The Great Pathfinder."

Fremont was the first candidate of the Republican Party for the office of President of the United States, and the first Presidential candidate of a major party to run on a platform in opposition to slavery. During the Civil War, he was appointed commander of the Union Army's Western Department by President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln took back that appointment one hundred days, later when Fremont ordered Missourians to free their slaves. This was one of many ill thought-out, misguided acts toward the abolition of slavery.

Biography

Frémont was born in Savannah, Georgia. His ancestry is unclear. According to the 1902 genealogy of the Frémont family, he was the son of Anne Beverley Whiting, a prominent Virginia society woman, who after his birth, married Louis-René Frémont, a penniless French refugee. H.W. Brands, however, in his biography of Andrew Jackson,[1] states that Fremont was the son of Anne and Charles Fremon, and that Fremont added the accented "e" and the "t" to his name later in life. Many confirm he was in fact illegitimate, a social handicap he overcame by marrying Jessie Benton, the favorite daughter of the very influential senator and slave owner from Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton.

Benton, Democratic Party leader for over 30 years in the Senate, championed the expansionist movement, a political cause that became known as Manifest Destiny. The expansionists believed that the North American continent, from one end to the other, should belong to the citizens of the United States, and that procuring those lands was the countryâs destiny. This movement became a crusade for politicians like Benton, and in his new son-in-law, making a name for himself as a western topographer, he saw in FrĂ©mont a great political asset. Benton was soon pushing through Congress appropriations of money to be used for surveys of the Oregon Trail (1842), Oregon Territory (1844), and the Great Basin and Sierra Mountains to California (1845). Through his power and influence, Benton got FrĂ©mont the leadership of these expeditions.

Expeditions

Frémont assisted and led multiple surveying expeditions through the western territory of the United States. In 1838 and 1839, he assisted Joseph Nicollet in exploring the lands between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, and in 1841, with training from Nicollet, he mapped portions of the Des Moines River.

Frémont first met American frontiersman Kit Carson on a Missouri River steamboat in St. Louis, Missouri, during the summer of 1842. Frémont was preparing to lead his first expedition and was looking for a guide to take him to South Pass. The two men made acquaintance, and Carson offered his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five-month journey, made with 25 men, was a success, and Fremont's report was published by the U.S. Congress. The Frémont report "touched off a wave of wagon caravans filled with hopeful emigrants" heading west.

During his expeditions in the Sierra Nevada, it is generally acknowledged that Frémont became the first European American to view Lake Tahoe. He is also credited with determining that the Great Basin had no outlet to the sea. He also mapped volcanoes such as Mount St. Helens.

Third expedition

On June 1, 1845, John Frémont and 55 men left St. Louis, with Carson as guide, on the third expedition. The stated goal was to "map the source of the Arkansas River," on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. But upon reaching the Arkansas, Frémont suddenly made a hasty trail straight to California, without explanation. Arriving in the Sacramento Valley in early winter 1846, he promptly sought to stir up patriotic enthusiasm among the American settlers there. He promised that if war with Mexico started, his military force would "be there to protect them." Frémont nearly provoked a battle with General José Castro near Monterey, which would have likely resulted in the annihilation of Frémont's group, due to the superior numbers of the Mexican troops. Frémont then fled Mexican-controlled California, and went north to Oregon, finding camp at Klamath Lake.

Following a May 9, 1846, Modoc Native American attack on his expedition party, Frémont retaliated by attacking a Klamath Native American fishing village named Dokdokwas, at the junction of the Williamson River and Klamath Lake, which took place May 10, 1846. The action completely destroyed the village, and involved the massacre of women and children. After the burning of the village, Carson was nearly killed by a Klamath warrior later that day: His gun misfired, and the warrior drew to fire a poison arrow; but Frémont, seeing Carson's predicament, trampled the warrior with his horse. Carson stated he felt that he owed Frémont his life due to this incident.

Mexican-American War

In 1846, Frémont was a Lieutenant Colonel of the U.S. Mounted Rifles (a predecessor of the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment). In late 1846, Frémont, acting under orders from Commodore Robert F. Stockton, led a military expedition of 300 men to capture Santa Barbara, California, during the Mexican-American War. Frémont led his unit over the Santa Ynez Mountains at San Marcos Pass and captured the Presidio, and the town. Mexican General Pico, recognizing that the war was lost, later surrendered to him rather than incur casualties.

On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of California following the Treaty of Cahuenga, which ended the Mexican-American War in California. However, U.S. Army general Stephen Watts Kearny, who outranked Frémont and believed that he was the legitimate governor, arrested Frémont and brought him to Washington, D.C., where he was convicted of mutiny. President James Polk quickly pardoned him in light of his service in the war.

In the winter of 1848, Fremont led an expedition with 33 men to locate passes for a proposed railway line from the upper Rio Grande to California. The trip was wrought with danger and Frémont and his men nearly froze to death. The expedition finally arrived in Sacramento in early 1849. Later, during the Californian Gold Rush, gold was discovered on his estate and he became a multi-millionaire.

Civil War

Frémont later served as a major general in the American Civil War and served a controversial term as commander of the Army's Department of the West from May to November 1861.

Frémont replaced William S. Harney, who had negotiated the Harney-Price Truce which permitted Missouri to remain neutral in the conflict as long as it did not send men or supplies to either side.

Frémont ordered his General Nathaniel Lyon to formally bring Missouri into the Union cause. Lyon had been named the temporary commander of the Department of the West to succeed Harney before Frémont ultimately replaced Lyon. Lyon, in a series of battles, evicted Governor Claiborne Jackson and installed a pro-Union government. After Lyon was killed in the Battle of Wilson's Creek in August, Frémont imposed martial law in the state, confiscating private property of secessionists and emancipating the state's slaves.

Abraham Lincoln, fearing the order would tip Missouri (and other slave states in Union control) to the southern cause, asked Frémont to revise the order. Frémont refused and sent his wife to plead the case. Lincoln responded by revoking the proclamation and relieving Frémont of command on November 2, 1861. In March 1862, Frémont was re-appointed to a different post (in West Virginia), but lost several battles to Stonewall Jackson and was relieved at his own request when ordered to serve under General John Pope.[2]

Radical Republicans

Frémont served from 1850 to 1851 as one of the first pair of Senators from California. In 1856, the new Republican Party nominated him as their first presidential candidate. He lost to James Buchanan, though he did surpass the American Party candidate, Millard Fillmore. Frémont lost California in the Electoral College.

Frémont was briefly the 1864 candidate of the Radical Republicans, a group of hard-line Republican abolitionists upset with Lincoln's position toward both the issues of slavery and post-war reconciliation with the southern states. This 1864 fracturing of the Republican Party splintered off into two new political parties: The anti-Lincoln Radical Republicans (convening in Cleveland starting on May 31, 1864) nominating Frémont, the Republicans' first standard-bearer from 1856, and; the political collaboration between pro-Lincoln Republicans and Democrats to form a new National Union Party (in convention in Baltimore during the first week in June 1864) in order to accommodate War Democrats who wished to separate themselves from the Copperheads.

Coincidentally, this creation of the National Union Party is the main reason why War Democrat Andrew Johnson was selected to be the Vice Presidential nominee. The former republicans who supported Lincoln also hoped that the new party would stress the national character of the war.

The Frémont-Radical Republicans political campaign was abandoned in September 1864, immediately after Frémont brokered a political deal with National Union Party candidate Lincoln to remove U.S. Posmaster General Montgomery Blair from his appointed federal office.

Later life

The state of Missouri took possession of the Pacific Railroad in February 1866, when the company defaulted in its interest payment, and in June 1866, the state, at private sale, sold the road to Frémont. Frémont reorganized the assets of the Pacific Railroad as the Southwest Pacific Railroad in August 1866, which in less than a year (June 1867) were repossessed by the state of Missouri when Frémont was unable to pay the second installment on his purchase price.

From 1878 to 1881, Frémont was the appointed governor of the Arizona Territory. The family eventually had to live off the publication earnings of wife Jessie. Frémont died in 1890, a forgotten man, of peritonitis in a hotel in New York City, and is buried in Rockland Cemetery, Sparkill, New York.

Legacy

Frémont collected a number of plants on his expeditions, including the first recorded discovery of the Single-leaf Pinyon by a European American. The standard botanical author abbreviation Frém. is applied to plants he described. The California Flannelbush, Fremontodendron californicum, is named for him.

Many places are named for FrĂ©mont. Four U.S. states named counties in his honor: Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, and Wyoming. Several states also named cities after him, such as California, Michigan, Nebraska, and New Hampshire. Likewise, Fremont Peak in the Wind River Mountains and Fremont Peak in Monterey County, California are also named for the explorer. The Fremont River, a tributary of the Colorado River in southern Utah, was named after FrĂ©mont, and in turn, the prehistoric Fremont culture was named after the riverâthe first archaeological sites of this culture were discovered near its course.

The U.S. Army's (now inactive) 8th Infantry Division (Mechanized) is called the Pathfinder Division, after John Frémont. The gold arrow on the 8th ID crest is called the "Arrow of General Frémont."

Notes

- â H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson, his Life and Times (New York: Doubleday, 2005) ISBN 9780385507387

- â Sunsite.utk.edu, U.S. Civil War GeneralsâUnion Generals (FrĂ©mont). Retrieved June 19, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brandon, William. The Men and the Mountain; Frémont's Fourth Expedition. New York: Morrow, 1955. ISBN 0837158737

- Chaffin, Tom. Pathfinder: John Charles Frémont and the Course of American Empire. New York: Hill and Wang, 2002. ISBN 978-0809075577

- Harvey, Miles. The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime. New York: Random House 2000. ISBN 9780375501517

- Stegmaier, Mark Joseph, David Humphreys Miller, and James F. Milligan. James F. Milligan: His Journal of Fremont's Fifth Expedition, 1853-1854, His Adventurous Life on Land and Sea. Glendale, Calif: A.H. Clark Co. 1988. ISBN 9780870621895

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2025.

- Memoirs of my Life by John C. Fremont

- Address of welcome to General John C. Fremont, August 1st, 1878

| Preceded by: None |

United States Senator (Class 1) from California 1850â1851 |

Succeeded by: John B. Weller |

| Preceded by: John Philo Hoyt |

Governor of Arizona Territory 1878â1881 |

Succeeded by: John Jay Gosper |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.