Klamath

The Klamath are a Native American tribe of the Plateau culture area in Southern Oregon. Together with the Modoc, and Yahooskin they now form the Klamath Tribes, a federally recognized confederation of three Native American tribes who traditionally inhabited Southern Oregon and Northern California in the United States. The tribal government is based in Chiloquin, Oregon.

An industrious, although warlike people, the Klamath quickly made trading partners with the European explorers in the early nineteenth century. They were then forced to live on a Reservation with their former rivals, the Modoc, and Yahooshkin, which led them to drastically change their lifestyle. Despite these challenges, the Klamath prospered, so much so that their federal recognition was "terminated" under a Federal policy to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream culture, and their reservation lands sold.

With the loss of their resources and federal support services, as well as their identity as a federally recognized tribe, the Klamath faced the collapse of their economy and society. Yet, they persevered, and in 1986 were able to regain federal recognition as the Klamath Tribes. Today they are working to revive and maintain the spiritual, cultural, and physical values and resources of their ancestors, and through this contribute to human society as a whole.

Classification

The Klamath people are grouped with the Plateau Indians—the peoples who originally lived on the Columbia River Plateau. They were most closely linked with the Modoc people.

Both peoples called themselves maklaks, meaning people. When they wanted to distinguish between themselves, the Modoc were called Moatokni maklaks, from muat meaning "South." The Klamath people were called Eukshikni, meaning "lake people."

History

Prior to the arrival of European explorers, the Klamath people lived in the area around the Upper Klamath Lake and the Klamath, Williamson, and Sprague rivers. They subsisted primarily on fish and gathered roots and seeds.

The Klamath were known to raid neighboring tribes (such as the Achomawi on the Pit River), and occasionally to take prisoners as slaves. They traded with the Chinookan people.

In 1826, Peter Skene Ogden, an explorer for the Hudson's Bay Company, first encountered the Klamath people, and he was able to establish trade with them by 1829. Although successful in trading, the Klamath soon suffered loss through disease born by Europeans.

The United States, the Klamaths, Modocs, and Yahooskin band of Snake tribes signed a treaty in 1864, establishing the Klamath Reservation, to the northeast of Upper Klamath Lake. The treaty had the tribes cede the land in the Klamath Basin, bounded on the north by the 44th parallel, to the United States. In return, the United States was to make a lump sum payment of $35,000, and annual payments totaling $80,000 over fifteen years, as well as providing infrastructure and staff for the reservation. The treaty provided that, if the Indians drank or stored intoxicating liquor on the reservation, the payments could be withheld and that the United States could locate additional tribes on the reservation in the future. Lindsay Applegate was appointed as the agent responsible for treaty negotiations and other U.S. government dealings with the Klamath.

After signing the 1864 treaty, members of the Klamath Tribes moved to the Klamath Reservation. The total population of the three tribes was estimated at about 2,000 when the treaty was signed. At the time there was tension between the Klamath and Modoc, and a band of Modoc led by Captain Jack left the reservation to return to Northern California. They were defeated by the US Army in the Modoc War (1872-1873), their leaders were executed or sentenced to life imprisonment, and the remaining Modoc were sent to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma.

In the reservation, Klamath took up cattle ranching, and quickly became successful. Other tribe members took advantage of their experience in trading, and worked hard in the freighting industry to become financially self-sufficient. In the latter part of the nineteenth century the country was developing rapidly, and with the arrival of the railroad at the beginning of the twentieth century timber from their reservation became a valuable commodity. By the 1950s the Klamath Tribes were self-sufficient and economically prosperous.

In 1954, the US Congress terminated federal recognition of tribal sovereignty of the Klamath, as part of an effort to assimilate American Indians judged ready to be part of mainstream culture. The reservation land was sold, with much of it incorporated into the Winema National Forest. Members of the Klamath Tribe reserve specific rights of hunting, fishing, and gathering of forest materials on their former reservation land.[1] However, the source of economic self-sufficiency, their land including forests and space for livestock was taken from them.[2]

With the growth of Indian activism in the late twentieth century, the tribes reorganized their government and, in 1986, regained federal recognition. However, the land of their former reservation was not returned.

Culture

The Klamath primarily fished and hunted waterfowl and small game along the inland waterways. They also depended heavily on wild plants, particularly the seeds of the yellow water lily (Wókas) which were gathered in late summer and ground into flour.

Language

The language of the Klamath tribe is a member of the Plateau Penutian family. Klamath was previously considered a language isolate.

The Klamath-Modoc (or Lutuamian) language has two dialects:

- Klamath

- Modoc

After contact with Europeans, Klamath began learning English for contact with the larger world while retaining the Klamath tribal language for use at home. However, as English became the language of literacy, used in formal educaiton, the Klamath language was not passed on to younger tribal members. It was preserved by elders, and in writing systems, such as that created by M.A.R. Barker in 1963.[3]

Traditions and Religious Beliefs

According to Klamath oral history, the Klamath people have lived in the Klamath Basin from time immemorial. They believe that stability is key to success, and that their continued presence in this land is essential to the well-being of of their homeland. "Work hard so that people will respect you" is the traditional advice given by elders, and the Klamath survived through their industriousness and faith.[4]

Legends tell about when the world and the animals were created, when the animals the Creator, sat together and discussed the creation of man. "Work hard so that people will respect you" is the standard of Klamath culture. It is based on the belief that everything they needed to live was provided for by the Creator. In the spring the c'waam (Suckerfish) swim up the Williamson, Sprague, and Lost Rivers to spawn, and the Klamath have traditionally held a ceremony to give thanks for their return. This celebration includes traditional dancing, drumming, feasting, and releasing of a pair of c'waam into the river.[4]

The Klamath believed that shamans, both male and female, had the power to heal and cure disease, as well as to control weather, success in hunting and raiding, and in finding lost items. These shamans obtained their power through fasting, prayer, and visions from spirits associated with nature.[5]

Lifestyle

The Klamath, unlike most tribes in Northern California, were warlike. They often raided neighboring tribes, taking captives to use as slaves. Upon signing the treaty in 1864 they agreed to give up slavery, however.

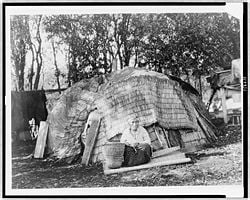

The Klamath had permanent winter dwellings. These were semi-subterranean pit-houses, wooden frames covered in earth over a shallow pit, with an entrance in the roof. Several families would live in one house. Circular wooden frame houses covered in mats were used in summer and on hunting trips. They also constructed sweat lodges of a similar style to their dwellings. These were used for prayer and other religious gatherings.

Klamath used dougout canoes to travel in the warm months, and snowshoes for winter travel.

Basketry was well developed into an art form, used for caps and shoes, as well as baskets for carrying food.

Contemporary life

The Klamath Tribes, formerly the Klamath Indian Tribe of Oregon, are a federally recognized confederation of three Native American tribes who traditionally inhabited Southern Oregon and Northern California in the United States: the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin. The tribal government is based in Chiloquin, Oregon.

The stated mission of the Tribes is as follows:

The mission of the Klamath Tribes is to protect, preserve, and enhance the spiritual, cultural, and physical values and resources of the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Peoples, by maintaining the customs and heritage of our ancestors. To establish a comprehensive unity by fostering the enhancement of spiritual and cultural values through a government whose function is to protect the human and cultural resources, treaty rights, and to provide for the development and delivery of social and economic opportunities for our People through effective leadership.[6]

There are currently around 3,500 enrolled members in the Klamath Tribes, with the population centered in Klamath County, Oregon.[6] Most tribal land was liquidated when Congress ended federal recognition in 1954 under its Indian termination policy. Some lands were restored when recognition was restored. The tribal administration currently offers services throughout the county.

The Klamath Tribes opened the Kla-Mo-Ya Casino (named after Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin) in Chiloquin, Oregon in 1997. It provides revenue which the tribe uses to support governance and investment for tribal benefit.

The Culture and Heritage Department of the Klamath Tribes develop projects designed to meet the social, spiritual and cultural needs of the Tribes,such as Tribal ceremonies and Culture Camps for Tribal youth. Annual events include the Restoration Celebration held the fourth weekend in August and the New Year’s Eve Sobriety Pow Wow.

The site protection program preserves ancestral and sacred sites and landscapes in cooperation with federal, state and local land management agencies, private developers and land owners. A Tribal Museum is planned.[7]

The Klamath Tribes Language Project is an effort to help keep alive and revitalize the Klamath Language. A basic course endorsed by the Culture and Heritage Department has been produced to introduce Klamath writing and pronunciation to tribal members.[8]

Klamath Indian Reservation

The present day Klamath Indian Reservation consists of twelve small non-contiguous parcels of land in Klamath County. These fragments are generally located in and near the communities of Chiloquin and Klamath Falls. Their total land area is 1.248 km² (308.43 acres). Few of the Klamath tribal members actually live on reservation land.

Water rights dispute

In 2001, an ongoing water rights dispute between the Klamath Tribes, Klamath Basin farmers, and fishermen along the Klamath River became national news. To improve fishing for salmon and the quality of the salmon runs, the Klamath Tribes pressed for dams to be demolished on the upper rivers. These dams have reduced the salmon runs and threatened the salmon with extinction.[9]

By signing the treaty of 1864,[10] the Klamath tribe ceded 20 million acres (81,000 km²) of land but retained 2 million acres (8,100 km²) and the rights to fish, hunt, trap, and gather from the lands and waters as they have traditionally done for centuries.[11]

When, as part of an effort at assimilation, the US Congress terminated the federal relationship with the Klamath Tribes in 1954, it was stated in the Klamath Termination Act, "Nothing in this [Act] shall abrogate any water rights of the tribe and its members... Nothing in this [Act] shall abrogate any fishing rights or privileges of the tribe or the members thereof enjoyed under Federal treaty."[11]

The states of California and Oregon have both tried to challenge Klamath water rights, but have been rebuffed. Local farmers tried unsuccessfully to claim water rights in the 2001 cases, Klamath Water Users Association v. Patterson and Kandra v. United States but these were decided in favor of the Department of Interior's right to give precedence to tribal fishing in its management of water flows and rights in the Klamath Basin.[11] In 2002 U.S. District Judge Owen M. Panner ruled that the Klamath Tribes' right to water preceded that of non-tribal irrigators in the court case United States vs. Adair, originally filed in 1975.[12]

In 2010, the final draft of the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (KBRA), "A Blueprint for Progress and Sustainability in the Klamath Basin," was released as a proposal to resolve the complex issues of the Klamath Basin.[13] The Klamath Tribes voted to support the KBRA.[14] In February, 2010, representatives of the Klamath, Yurok, and Karuk tribes, together with political leaders from federal, state and local governments gathered to sign the Klamath Restoration Agreements at the state capital in Salem, Oregon. Dam removal is scheduled to begin in 2020, pending federal legislation to authorize the plan.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Fremont-Winema National Forests History. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Termination The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ M.A.R. Barker, Klamath Dictionary (University of California Press, 1963).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 History The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Barry M. Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0195138771), 259.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Klamath Tribal Culture. The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ↑ Culture and Heritage Department. The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ↑ Klamath Tribes Language Project. The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ↑ Top Ten Reasons to Remove Klamath Dams Klamath Restoration Agreements. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ Treaty with the Klamath, etc. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Klamath Tribes' Water Rights." The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Judge affirms Klamath Tribes' water right of time immemorial", U.S. Water News Online, March 2002. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement Klamath Restoration Agreements.

- ↑ Klamath Tribes Historic Vote Passes Overwhelmingly Klamath Tribes Press Release, January 19, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ Historic Klamath Restoration Agreements Signed Klamath Restoration Agreements.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barker, M.A.R. Klamath Dictionary. University of California Press, 1963. ASIN B008YWCMCK

- Gatschet, Albert Samuel. The Klamath Indians of Southwestern Oregon. Forgotten Books, 2012. ASIN B008G2FKVS

- Hale, H. "The Klamath Nation: the country and the people." Science, 19(465) (1892).

- Mithun, Marianne. The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0521298759

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744.

- Wolf, Edward C. Klamath Heartlands: A Guide to the Klamath Reservation Forest Plan. Oregon State University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0967636436

External links

All links retrieved March 3, 2025.

- Klamath Tribal Council records

- The Klamath Tribes Website

- Klamath Tribes Oregon Blue Book

- Fremont-Winema National Forest

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.