Goguryeo

| Goguryeo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul: | 고구려 |

| Hanja: | 高句麗 |

| McCune-Reischauer: | Koguryŏ |

| Revised Romanization: | Goguryeo |

| Chinese name | |

| Traditional Chinese: | 高句麗 |

| Simplified Chinese: | 高句丽 |

| Hanyu Pinyin: | Gāogōulì |

| Wade-Giles: | Kao-kou-li |

| Russian name | |

| Cyrillic: | Когурё |

| IPA: | kogurʲo |

The ancient kingdom Goguryeo, occupying southern Manchuria (present-day northeast China), southern Russian Maritime province, and the northern and central parts of the Korean peninsula, was one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, along with Baekje and Silla, for nearly seven centuries at the beginning of the first millennium. Considered an important regional kingdom in Manchuria by the People's Republic of China, Goguryeo actively participated in the power struggle for control of the Korean peninsula and as well conducted foreign affairs with associated polities in China and Japan.

The 'Samguk Sagi, a twelfth-century C.E. Goryeo text, puts Goguryeo's founding at 37 B.C.E. by Jumong, a prince from Buyeo. Archaeological evidence suggests Goguryeo culture existed since the second century B.C.E., around the fall of Gojoseon, an earlier kingdom that also occupied southern Manchuria and northern Korea. Goguryeo, a major regional power of East Asia, fell in defeat to a Silla-Tang alliance in 668 C.E. After suffering defeat, Goguryeo was divided between the Tang Dynasty, Unified Silla, and Balhae. The tribal state of Khitan in Manchuria may have also taken some of the territory.

|

Jeulmun Period

|

| History of Manchuria |

|---|

| Not based on timeline |

| Early tribes |

| Gojoseon |

| Yan (state) | Gija Joseon |

| Han Dynasty | Xiongnu |

| Donghu | Wiman Joseon |

| Wuhuan | Sushen | Buyeo |

| Xianbei | Goguryeo |

| Cao Wei |

| Jin Dynasty (265-420) |

| Yuwen |

| Former Yan |

| Former Qin |

| Later Yan |

| Northern Yan |

| Mohe | Shiwei |

| Khitan | Kumo Xi |

| Northern Wei |

| Tang Dynasty |

| Balhae |

| Liao Dynasty |

| Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) |

| Yuan Dynasty |

| Ming Dynasty |

| Qing Dynasty |

| Far Eastern Republic (USSR) |

| Republic of China |

| Manchukuo |

| Northeast China (PRC) |

| Russian Far East (RUS) |

History

Founding

According to the Samguk Sagi, a prince from the kingdom of Eastern Buyeo, named Jumong, fled after a power struggle with other princes of the Buyeo court [1] and founded the Goguryeo state in 37 B.C.E. in a region called Jolbon Buyeo, usually thought to be located in the middle of the Yalu and T'ung-chia river basin, overlapping the current China-North Korea border. Some scholars believe that Goguryeo may have been founded in the second century B.C.E. [2]

The first mention of the word Goguryeo or "高句麗" appeared in the geographic monographs of the Han Shu, stating that the nation's founding as 113 B.C.E. as a region under the jurisdiction of the Xuantu commandery.[3] The Old Book of Tang states that Emperor Taizong of Tang refers to Goguryeo's history as being some 900 years old. In 75 B.C.E., a group of Yemaek tribes (a people that made up the original Goguryeo stock), which may have included Goguryeo, made an incursion into China's Xuantu commandery west from the Amnok River valley. [4]

The weight of documentary evidence from the Old and New Histories of Tang, the Samguk Sagi, the Nihon Shoki, as well as other ancient sources support a 37 B.C.E. or "middle"-first-century B.C.E. foundation date for Goguryeo. Archaeological evidence supports the claim that centralized groups of Yemaek tribes settled in the second century B.C.E., although a lack of direct evidence suggests that those Yemaek groups had little or no concept of themselves as Goguryeo. The Han Shu has the first mention of Goguryeo as a group type associated with Yemaek tribes, referring to a Goguryeo revolt in 12 C.E., where they break away from Xuantu influence.[5] During that time, the Goguryeo ruler, given the title of "marquis" (侯) by the Xuantu administrators, began calling himself the Chinese title of "wang" (王) or king.

The leadership from Buyeo appears to have fled their kingdom and integrated with existing Yemaek chiefdoms, leading some to conclude that the founding people of Goguryeo came from a blend of the Buyeo and Yemaek people.[6] The San Guo Zhi, in the section titled "Accounts of the Eastern Barbarians," states that the Buyeo and Yemaek people came from the same ethnic line and spoke a common language.[7]

Jumong and the Foundation Myth

The Stele of Great King Gwanggaeto states that Jumong existed in the fourth century C.E., the earliest mention of Jumong. Jumong is the Korean transcription of the hanja 朱蒙 (Jumong, 주몽), 鄒牟(Chumo, 추모), or 仲牟 (Jungmo, 중모). The Stele proclaims Jumong the first king and ancestor of Goguryeo, the son of the king of Buyeo and the river deity Habaek.[8] The Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa paint additional details and name Jumong's mother as Yuhwa. The Samguk Yusa described Jumong's biological father, Hae Mosu, as a "strong man" and "a heavenly prince."[9]

The Samguk Sagi presents Hae Mosu as a sky deity who had seduced Yuhwa. Later, the King of Buyeo gave refuge to Yuhwa in the Buyeo court and adopted Jumong as his own son, making Jumong a prince of Buyeo. According to the story, Jumong, very talented, especially in archery and equestrian arts, made the crown prince jealous. The crown prince had plans to have Jumong killed and upon learning of the plot, Jumong fled Buyeo.[10] The Stele and later Korean sources disagree on which of the Buyeo states Jumong came from. The Stele records that he came from North Buyeo and the Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa report he came from East Buyeo. Jumong eventually journeyed to the Jolbon Buyeo confederacy, where he married the daughter of the ruler and subsequently became king himself, founding Goguryeo with a small group of followers from his native country.

Jumong received the surname, Hae (解), the name of the Buyeo rulers. According to the Samguk Yusa, Jumong changed his surname to Ko (高), in conscious reflection of his divine parentage.[11] Legend records that Jumong conquered the tribal states of Biryu (비류국, 沸流國) in 36 B.C.E., Haeng-in (행인국, 荇人國) in 33 B.C.E., and North Okjeo in 28 B.C.E.

First Wave of Expansion and Centralization of Tribal Leagues

Developing from a league of various Yemaek tribes to an early state, Goguryeo rapidly expanded its power from their original basin of control in the Hun River drainage. The Goguryeo homeland lacked arable land and could barley sustain its population. Goguryeo, raiding their neighbors, expanded their resource base. During the rein of King Taejo of Goguryeo in 53 C.E., five local tribes reorganized into five centrally ruled districts of the kingdom. The king controlled foreign relations and the military. Aggressive military activities may have allowed Goguryeo to exact tribute from their tribal neighbors and to even dominate them politically and economically.[12]

King Taejo conquered the Okjeo tribes of northeast Korea as well as the eastern Ye and other tribes in southeastern Manchuria and northern Korea. From the increase of resources and manpower that those subjugated tribes gave him, Goguryeo attacked Han China's Commanderies of Lelang, Xiantu, and Liaodong in the Korean and Liaodong peninsulas, becoming fully independent from the Han Commanderies.[13]

Generally, Taejo allowed the conquered tribes to retain their chieftains, but required them to report to governors related to Goguryeo's royal line and pay heavy tribute. Taejo and his successors utilized their increasing resources to continue expanding to the northwest. New laws regulated peasants and the aristocracy; the central aristocracy continued to absorb tribal leaders. Royal succession changed from fraternal to patrilineal, strengthening the royal court.[14]

The expanding Goguryeo kingdom entered into direct military contact with the Liaodong commandery. Pressure from Liadong forced Goguryeo to move its capital in the Hun River valley to the Yalu River valley, near Mount Wandu in the current-day Dongou region of China's Jilin province [15]

Goguryeo-Wei War

Chaos followed the fall of the Han Dynasty with former Han commanderies breaking free from control and falling under the rule of independent warlords. Surrounded by those commanderies, governed by aggressive warlords, Goguryeo moved to improve relations with the newly created Wei Dynasty of China and sent tribute in 220 C.E. In 238 C.E., Goguryeo entered into a formal alliance with the Wei to destroy the Liaodong commandery. When Wei finally conquered the Liaodong, cooperation between Wei and Goguryeo fell apart and Goguryeo attacked the western edges of Liaodong, which incited a Wei counterattack in 244. On that occasion, Wei reached and destroyed the Goguryeo capital at Wandu. The Goguryeo king, with his army destroyed, fled alone and sought refuge with the Okjeo tribes in the east.[16]

|

Revival and Further Expansion

The Wei armies chose not to occupy Goguryeo and left after they believed that the kingdom was destroyed. After only 70 years, Goguryeo rebuilt its capital at Wandu and again began to raid Liaodong, Lelang, and Xuantu commanderies. As Goguryeo extended its reach into the Liaodong Peninsula, the last Chinese commandery at Lelang was destroyed by Micheon of Goguryeo in 313, and from that time the Three Kingdoms dominated the Korean Peninsula.

The expansion met temporary setbacks when in 342, Former Yan, a Chinese Sixteen Kingdoms state of Xianbei ethnicity, attacked Goguryeo’s capital, then at Wandu (丸都, in modern Ji'an, Jilin), and in 371, King Geunchogo of Baekje sacked Goguryeo’s largest city, Pyongyang, and killed King Gogukwon of Goguryeo in battle.

Turning to domestic stability and the unification of various conquered tribes, Sosurim of Goguryeo proclaimed new laws, embraced Buddhism as the national religion in 372, and established a national educational institute called the Taehak (태학, 太學).

Gwanggaeto the Great

The greatest territorial expansion of Goguryeo began during the reigns of King Gwanggaeto the Great and his son King Jangsu.

Gwanggaeto reigned from 391 to 412, during which Goguryeo conquered 64 walled cities and 1,400 villages from one campaign against Buyeo alone, destroyed Later Yan and annexed Buyeo and Mohe tribes to the north. He also subjugated Baekje, contributed to the dissolution of the Gaya confederacy, and turned Silla into a protectorate in wars against Gaya and Wa (Japan). In doing so, he brought about a loose unification of Korea that lasted about 50 years. The Gwanggaeto Stele, erected in 414 in the southern part of Manchuria, records his accomplishments. By the end of his reign, Goguryeo had achieved undisputed control of southern Manchuria, and the northern and central regions of the Korean Peninsula.

Jangsu Taewang, ascending to the throne in 413, moved the capital to Pyongyang in 427, evidence of the intensifying rivalries with the two Korean kingdoms of Baekje and Silla to its south. Jangsu, like his father, continued Goguryeo's territorial expansion into Manchuria and reached the Eastern Songhua River, which marked Goguryeo's farthest reach to the north. Jangsu also advanced into the east, occupying part of Russia's Primorsky Krai. During that period, Goguryeo territory included three-fourths of the Korean Peninsula, including today's Seoul, and most of Manchuria and the Russian maritime province.

Goguryeo considered itself the center of the world, and founder Jumong the son of heaven. The title of the ruler, Taewang, while literally translated as the greatest of the kings, is often translated to mean emperor. In the late fifth century, Goguryeo absorbed Bukbuyeo and more Mohe and Khitan tribes, competed with Northern Wei in the north, and continued its strong influence over Silla.

Internal Strife

Goguryeo reached its zenith in the sixth century and then steadily declined. King Anwon, assassinated and succeeded his brother King Anjang, inaugurating a period of increased aristocratic factionalism. A political schism deepened as two factions advocated different princes for succession, leading to the crowning of eight-year-old Yang-won. Renegade magistrates with private armies appointed de facto rulers called Daedaero, continuing the power struggle.

Taking advantage of Goguryeo's internal struggle, a nomadic group called the Tuchueh attacked Goguryeo's northern castles in the 550s and conquered some of Goguryeo's northern lands. Baekje and Silla allied to attack Goguryeo from the south in 551, which weakened Goguryeo more, as civil war continued among feudal lords over royal succession. Goguryeo fought back to reclaim the Seoul region that had been taken by Silla, and maneuvered to effectively sever the Silla–Baekje alliance. During the war, Goguryeo lost much of the fertile Han River valley to Silla.

Conflicts of the Late Sixth and Seventh Centuries

Throughout its history, Goguryeo repelled numerous attacks from a number of Chinese dynasties while disputing with Silla and Baekje. Goguryeo considered Silla and Baekje allies at alternating times. During the late sixth and early seventh century, Goguryeo often conflicted with Chinese dynasties such as the Sui and Tang. The Sui invasions ended in failure for Sui, and effectively crippled its economic and military capability. The Eastern Göktürk, a khanate in northwestern China and near Mongolia, allied with Goguryeo and conducted trade with Goguryeo. Xueyantuo, a successor state to the Eastern Göktürk state, opened a second front on the Tang Dynasty when a Silla–Tang alliance attacked Goguryeo near the end of Goguryeo's rule.

Goguryeo-Sui Wars

The Sui Dynasty, founded in 581, grew in power and emerged as a powerful dynasty in China. Goguryeo's expansion conflicted with the Sui Dynasty and increased tensions. In 598, the Sui, provoked by Goguryeo military offensives in the Liaosuh region, attacked Goguryeo in the first of the Goguryeo-Sui Wars. In that campaign, as with those that followed in 612, 613, and 614, the Sui failed, losing three-fourths of its military capability. Ninety percent of the first expedition never returned. The 613 and 614 campaigns aborted after launching. The 613 campaign terminated when the Sui general Yang Xuangan rebelled against Emperor Yang of Sui. The 614 campaign terminated with Goguryeo's offer to surrender and return Husi Zheng (斛斯政), a defector who had fled to Goguryeo, allowing Emperor Yang to execute Husi. Emperor Yang later planned another attack on Goguryeo in 615, but, due to Sui's deteriorating internal state, never launched it. Rebellions against Emperor Yang's rule weakened Sui. Further attacks became impossible when the soldiers in the Sui heartland refused to send logistical support.

The campaign of 612 proved to be one of Sui's most disastrous campaigns, in which Sui mobilized at least 1,138,000 combat troops. General Eulji Mundeok led the Goguryeo troops to victory by luring the Sui troops into a trap outside of Pyongyang. At the Battle of Salsu River, Goguryeo soldiers released water from a dam, which overwhelmed the Sui army and drowned nearly every Sui soldier. Of the original 310,000 soldiers, a mere 2,700 returned to China. Sui attacked three more times, all of which Goguryeo repulsed.

The wars depleted the national treasury of the Sui Dynasty and after revolts and political strife, the Sui Dynasty disintegrated in 618. The wars also exhausted Goguryeo's strength and its power declined as well.

Goguryeo-Tang War and Tang-Silla Alliance

After Goguryeo repelled attacks from the Sui Dynasty, the successor [[Tang Dynasty] attacked Goguryeo as well. Under Li Shih min (Tang Taizong), the Tang Dynasty attacked Goguryeo in revenge of the Sui. The Chinese failed to capture strategic points in numerous attacks. The Tang forged an alliance with Goguryeo's rival Silla after defeating Goguryeo's western ally, the Göktürks. That, combined with Goguryeo's increasing political instability following the 642 murder of King Yeongnyu at the hands of the military general Yeon Gaesomun, increased tensions between Tang and Goguryeo, as Yeon took an increasingly provocative stance against Tang.

Taizong launched another attack against Goguryeo in 645; Goguryeo repelled the attack at Ansi Fortress. Goguryeo leaders Yeon Gaesomun and Yang Manchun led the successful defense. In the end, Taizong failed to capture Ansi, and the Tang army withdrew after suffering large losses during the siege of Ansi and after running out of food supplies. After Taizong's death in 649, a Tang army attacked Goguryeo again in 661 and 662, but for as long as Yeon Gaesomun lived, the Tang failed to conquer Goguryeo. Following the defection of Yeon Namseng, the son of Yeon Gaesomun and the surrender of numerous cities in northern Goguryeo, the Tang army bypassed the Liaodong region and captured Pyongyang, the capital of Goguryeo, while Yeon Jeongto, the younger brother of Yeon Gaesomun, surrendered his forces to the Silla general Kim Yushin, who advanced from the south. In November 668, Bojang, the last king of Goguryeo, surrendered to Tang Gaozhong.

Goguryeo's Fall

Goguryeo's ally in the southwest, Baekje, fell to the Silla–Tang alliance in 660; the victorious allies continued their assault on Goguryeo for the next eight years. Meanwhile, in 666 (though dates vary from 664–666), Yeon Gaesomun died and civil war ensued among his three sons. Silla–Tang eventually vanquished the weary kingdom, which had been suffering from a series of famines and internal strife. Goguryeo finally fell in 668. Tang forces captured and took into exile Goguryeo's last king Bojang. Silla thus unified most of the Korean Peninsula in 668. But the kingdom's reliance on China's Tang Dynasty had its price. Tang set up the Protectorate General to Pacify the East, or Andong protectorate, governed by Xue Rengui, but faced increasing problems ruling the former inhabitants of Goguryeo, as well as Silla's resistance to Tang's remaining presence on the Korean Peninsula. Silla had to forcibly resist the imposition of Chinese rule over the entire peninsula, but their strength stopped at the Taedong River.

In 677, Tang crowned Bojang "King of Joseon" and put him in charge of the Liaodong commandery of the Protectorate General to Pacify the East. King Bojang continued to cause trouble for Tang, fermenting rebellions in an attempt to revive Goguryeo, organizing Goguryeo refugees and allying with the Mohe tribes. Tang eventually exiled him to Szechuan in 681 where he died the following year.

Revival Movements

After the fall of Goguryeo in 668, many Goguryeo people rebelled against the Tang and Silla by starting Goguryeo revival movements. Geom Mojam, and Dae Jung-sang, along with several others, were among those that started revival movements. The Tang Dynasty tried but failed to establish several commanderies to rule over the area. Dae Joyeong, the son of a former Goguryeo general led the first successful revival movement, regaining most of Goguryeo's northern land and establishing the kingdom of Balhae in 698, 30 years after the fall of Goguryeo. Silla controlled the Korean Peninsula south of the Taedong River, while Balhae conquered northern Korea and Manchuria.

Balhae stood as a successor state to Goguryeo. The Liao Dynasty conquered Balhae in 926 after which many people migrated down to Goryeo. Few accounts or records of Balhae survive. Historians call the time of Balhae and Unified Silla the North-South State period of Korean history. In the early tenth century, Taebong (also called Hu-Goguryeo ("Later Goguryeo")), rose briefly in rebellion against Silla laying hold of the claim to succeed Goguryeo. Goryeo, the state that replaced Silla to rule the unified Korean Peninsula, also claimed that lineage.

Aspects of Goguryeo Civilization

Military

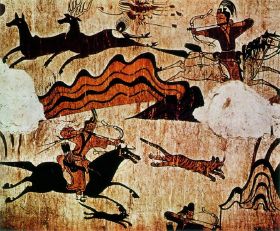

Goguryeo possessed a powerful military, especially during the rule of King Gwanggaeto, although records tell little more than that. A Tang treatise of 668 records a total of 675,000 displaced personnel and 176 military garrisons after the surrender of King Bojang. Goguryeo required every man to serve in the military or pay extra grain tax. Cavalry, mounted archers, and infantry, famous for their horned helmets as well as spikes attached to the bottom soles of their boots, formed the core of Goguryeo's military.

Culture

Climate, religion, and the tense society that people dealt with due to the numerous wars Goguryeo waged, shaped Goguryeo culture. Few records of Goguryeo's culture remain.

Lifestyle

The inhabitants of Goguryeo wore a predecessor of the modern hanbok, just as the other cultures of the Three Kingdoms. Murals and artifacts depict dancers wearing elaborate white dresses. The diet of the Goguryeo people included rice and barley. Beans supplemented their diet, while they steamed their rice, in a way similar throughout East Asia. A seasoned meat, maegjeok, Bulgogi's predecessor, usually accompanied meals.

Festivals and Pastimes

Goguryeo people loved to drink, sing, and dance. Games such as wrestling attracted curious spectators. The Dongmaeng Festival, held every October, paid homage to their gods. Often, the king performed rites to his ancestors. Following ceremonies, the citizens enjoyed elaborate feasts, games, and other activities. Hunting, a common activity for men, also served as military training for young men. Hunting parties rode on horses and hunted deer and other game with bows-and-arrows. Archery contests and horse riding proved a popular recreation. Those activities helped Goguryeo develop an excellent cavalry.

Religion

Goguryeo people worshipped ancestors, considering them supernatural. The people worshipped and respected Jumong, the founder of Goguryeo. At the annual Dongmaeng Festival, they performed religious rites to ancestors and gods. In Goguryeo, people considered mythical beasts and animals sacred. They worshipped the phoenix, dragon, and the Chinese three-legged bird of the Zhou Dynasty, considering the Chinese three-legged bird the most powerful of the three. Paintings of mythical beasts exist in Goguryeo king tombs today.

Buddhism first entered Goguryeo in 372. Goguryeo became the first kingdom in the region to adopt Buddhism. The government recognized and encouraged the teachings of Buddhism and built many monasteries and shrines during Goguryeo's history. Passing from Goguryeo, Buddhism thrived in Silla and Baekje.

Cultural Impact

Noted for the vigor of its imagery, Goguryeo art has been preserved for the most part in tomb paintings. Finely detailed art decorates Goguryeo tombs and other murals. Designs found throughout northern China and northeast Asia influenced many of the art pieces.

Goguryeo's floor heating system, ondol, and hanbok number among their cultural legacies.

Language

Along with many other kingdoms in East Asia, Goguryeo used Chinese characters and wrote in classical Chinese. Only a few words of the Goguryeo language survive, enough to suggest a similarity to the language of Silla and influenced by the Tungusic languages. Supporters of the Altaic language family often classify the Goguryeo language as a member of that language family. Most Korean linguists consider the Goguryeo language the closest to the Altaic languages out of the Three Kingdoms that followed Gojoseon.

Baekje and Goguryeo bore striking similarities, giving support to the legends that describe Baekje as founded by the sons of Goguryeo's founder. The Goguryeo names for government posts bore a resemblance to those of Baekje and Silla. The American linguist Christopher Beckwith has also noted similarities in certain vocabulary with Old Japanese. Some linguists propose the so-called "Buyeo languages" family that includes the languages of Buyeo, Goguryeo, Baekje, and Old Japanese. Chinese records suggest a similarity between the languages of Goguryeo, Buyeo, East Okjeo, and Gojoseon, while Goguryeo language differed significantly from that of Malgal (Mohe). Some words of Goguryeo origin exist in the old Korean language (early tenth-late fourteenth centuries), but Silla-originated ones replaced most before long.

Legacy

Goguryeo remains of walled towns, fortresses, palaces, tombs, and artifacts have been found in North Korea andManchuria, including ancient paintings in a Goguryeo tomb complex in Pyongyang. Some ruins are also still visible in China, for example at Onyeosan ("Five Maiden Peaks") near Ji'an in Manchuria, along the present border with North Korea, site of the state's first permanent capital.

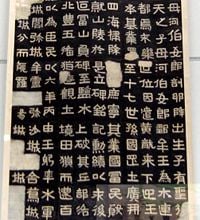

Ji'an is also home to a large collection of Goguryeo era tombs, including what Chinese scholars consider the tombs of kings Gwanggaeto and his son Jangsu, as well as perhaps the best-known Goguryeo artifact, the mammoth funeral stele of King Gwanggaeto, around whose interpretation a debate still rages. The stele is one of the primary sources for pre-fifth century Goguryeo history.

World Heritage Site

UNESCO added the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs in present-day North Korea and Capital Cities and Tombs of the Ancient Koguryo Kingdom in present-day China to the World Heritage Sites in 2004.

Notes

- ↑ Mark E. Byington, “A history of the Puyŏ State, its People, and its Legacy,” PhD Thesis (Harvard University, May 2003), 234.

- ↑ Daniel Kane, VI. Puyo-Koguryo, Bibliography of Ancient Korea and the Samguk sagi. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ↑ Christopher I. Beckwith, Koguryo: The Language of Japan's Continental Relatives, Brill's Japanese Studies Library, vol. 21 (Boston: Brill, 2004 ISBN 9789004139497), 33.

- ↑ Byington, "A history of the Puyo State," 194.

- ↑ Ibid., 233.

- ↑ Song Nai Rhee, “Secondary State Formation: The Case of Koguryo State,” in Pacific Northeast Asia in Prehistory: Hunter-fisher-gatherers, Farmers, and Sociopolitical Elites, ed. C. Melvin Aikens and Song Nai Rhee (Washington State University, 1993 ISBN 0-87422-092-0), 191–196.

- ↑ Peter H. Lee and William Theodore De Bary, Sources of Korean Tradition: Introduction to Asian Civilizations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997 ISBN 9780231105668), 7–11.

- ↑ Ibid., 24–25.

- ↑ Ilyon, Samguk Yusa: Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea, trans. Tae Hung Ha and Grafton K. Mintz (Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 1972), 45.

- ↑ Ibid., 46.

- ↑ Ibid., 46–47

- ↑ Gina L. Barnes, State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, Durham East Asia Series (Richmond: Curzon, 2001 ISBN 9780700713233), 22.

- ↑ Ki-Baik Lee, A New History of Korea (Harvard University Press, 1984 ISBN 9780674615755), 24.

- ↑ Ibid., 36.

- ↑ Gina L. Barnes, State Formation in Korea, 22–23.

- ↑ Ibid., 23.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gyeonggi Provincial Museum. “Goguryeo-Korea, Among Us: Special Exhibition.” Yongin City: Gyeonggi Provincial Museum, 2005.

- Ha, Ilyon, and Kim. Tales from the Three Kingdoms: Sam-guk sŏl-hwa. Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 1970.

- Ilyon. Samguk Yusa: Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea. Trans. Tae Hung Ha and Grafton K. Mintz. Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 1972.

- Lee, Gil-sang. Exploring Korean History through World Heritage. Seongnam-si: Academy of Korean Studies, 2006. ISBN 978-8971055519

- Lee, Ki-baik. A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0674615755

- Seth, Michael J. A Concise History of Korea: From the Neolithic Period through the Nineteenth Century. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-0742540040

External Links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.