Feng shui

| Feng shui | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese: | 風水 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese: | 风水 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning: | wind-water | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||||

| Tagalog: | punsoy | ||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Kanji: | 風水 | ||||||||||||

| Hiragana: | ふうすい | ||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul: | 풍수 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja: | 風水 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||

| Thai: | ฮวงจุ้ย (Huang Jui) | ||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||

| Vietnamese: | Phong thủy | ||||||||||||

In ancient times as well as today, Feng Shui, (風水) pronounced in English as [fʊŋ'ʃweɪ] ("fung shway"), was known as "Kan-Yu" which means 'The Law of Heaven and Earth.’ [1] Feng shui is the ancient Chinese practice of placement and arrangement of space to achieve harmony between human beings and the environment. Feng shui literally translates as "wind-water." This is a cultural shorthand taken from the following passage of the Zhangshu (Book of Burial) by Guo Pu ( 郭璞) of the Jin Dynasty(晋朝; 265–420) [2]

The qi (氣) that rides the wind stops at the boundary of water.[3]

Feng shui considers factors such as space, weather, astronomy, and geomagnetism in determining the most auspicious location for a building or an activity. Its guidelines are compatible with many techniques of agricultural planning, as well as architecture and furniture arrangement. Proponents claim that feng shui has an effect on health, wealth, and personal relationships.

Introduction

Feng shui is often identified as a form of geomancy, or divination by geographic features, but it is mainly concerned with understanding the relationships between nature and human beings, in order to create harmony. Early feng shui relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe [4] Chinese often used the celestial pole, determined by the pole stars, to locate the north-south axis of settlements. This technique explains why Shang palaces at Xiaotun lie 10° east of due north. In some cases, as Paul Wheatley observed[5], they bisected the angle between the directions of the rising and setting sun to find north. This technique provided the more precise alignments of the Shang walls at Yanshi and Zhengzhou ( 鄭州).

The earliest evidence for feng shui to date is provided by the Yanshao ( 仰韶文化; 5000 – 3000 B.C.E.) and Hongshan (红山文化 ; 4700 to 2900 B.C.E.) cultures. Professor David Pankenier and his associates reviewed astronomical data for the time of the Banpo (半坡) dwellings (4000 B.C.E.) to show that the asterism (a pattern of stars observed from earth) called Yingshi (Lay out the Hall, in the Warring States period and early Han era) corresponded to the sun's location at this time. Centuries before, the asterism Yingshi was known as Ding and was used to indicate the appropriate time to build a capital city, according to the Shijing. Apparently an astronomical alignment ensured that Banpo village homes were sited so that they received the maximum heat from the sun (solar gain).[6]

A grave at Puyang (radiocarbon dated 5,000 BP) that contains mosaics of the Dragon and Tiger constellations and Beidou( 北斗)(Dipper) is similarly oriented along a north-south axis.[7] The presence of both round and square shapes in the Puyang tomb, and at Hongshan culture ceremonial centers, suggests that the gaitian cosmography (heaven-round, earth-square) was present in Chinese culture long before it appeared in the Zhou Bu Suan Jing.[8]

Cosmography that bears a striking resemblance to modern feng shui compasses (and computations) was found on a jade unearthed at Hanshan (c. 3000 B.C.E.). The design is linked by the contemporary Chinese historian, Li Xueqin, to the liuren astrolabe, zhinan zhen, and Luopan. [9]

All capital cities of China followed rules of Feng Shui for their design and layout. These rules were codified during the Zhou era (1122 – 26 B.C.E.) in the "Kaogong ji" (Manual of Crafts). Rules for builders were codified in the "Lu ban jing" (Carpenter's Manual). Graves and tombs also followed rules of feng shui. From the earliest records, it seems that the rules for the structures of the graves and dwellings were the same.

Instrumentation

History

Feng shui devices existed before the invention of the magnetic compass, which occurred comparatively late in the long history of feng shui. According to the Zhouli, the original device may have been a gnomon, although Yao, Huangdi, and other figures were said to possess devices such as a south-pointing chariot.

One was the luopan, a reticulated plate used to correlate the solar and lunar calendars and for astronomical observation." [10]The oldest excavated examples of instruments used for feng shui are liuren astrolabes. These consist of a lacquered, two-sided board with astronomical sightlines. Liuren astrolabes have been unearthed from tombs that date between 278 B.C.E. and 209 B.C.E. The markings are virtually unchanged from the astrolabe to the first magnetic compasses.[11]

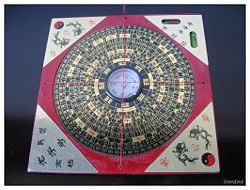

Some feng shui disciplines required the use of the magnetic compass. [12], This compass could be a Luopan (Chinese Feng Shui compass of the types San Yuan, San He, and Zong He) or one of the earlier versions such as a south-pointing spoon (zhinan zhen).

The history of the Luopan compass goes back to the Zhou dynasty (770-476 B.C.E.), when emperor Shing combined knowledge of the compass with that of the I-ching. The compass consists of a magnetic needle that points towards magnetic North, not true North. The foundation of the I-ching is in the trigrams. In traditional compass techniques, these trigrams are used for divination. The traditional luopan has thirty-six rings inscribed with information. The trigrams occupy the first circle of the luopan. The way in which the rings of the luopan line up with the compass, and the combination of the reading of these rings, determines a person’s fortune.

Foundation Theories

The goal of feng shui as practiced today is to situate the human-built environment on spots with good qi. The "perfect spot" is a location and an axis in time. Some areas are not suitable for human settlement and should be left in their natural state.

Some current techniques can be traced to Neolithic China, while others were added in later times (most notably during the Han dynasty, the Tang, and the Ming). Today, to determine a perfect spot, local manifestations of qi must be assessed for quality. Quality is determined by observations and by using a compass (luopan).

Qi (ch'i)

Qi is a difficult word to translate and is often left untranslated. Literally, the word “qi” means "air." In feng shui, "qi" means "flow of energy." Max Knoll suggested in a 1951 lecture that qi is a form of solar radiation.[13]

A luopan is used for many purposes, including the detection of the flow of qi. Compasses reflect local geomagnetism which includes geomagnetically induced currents caused by space weather.[14] It could be said that feng shui that is, feng shui is qimancy, or qi divination, a method for assessing the quality of the local environment and the effects of “space weather” (changing environmental conditions in outer space) [15]

Beliefs developed during the Axial Age (the period from 800 - 200 B.C.E., during which similarly revolutionary thinking appeared in China, India and the Occident), including feng shui, hold that the heavens influence life on Earth. It has been determined that “space weather” exists and can have profound effects on technology such GPS, power grids, pipelines, communication and navigation systems, surveys; and on the internal orienting faculties of birds and other creatures.[16] [17][18] Atmospheric scientists have even suggested that “space weather” creates fluctuations in market prices.[19][20]

Polarity

Polarity is expressed in feng shui as Yin and Yang. The polarity within feng shui is buildings of the living (yang) and buildings of the dead (yin).

Magnetic North and Luopan compass

The stability of Magnetic North is critical for the accuracy of reading a compass. Earth has an electromagnetic field. Our solar sun also has an electromagnetic field. Our solar sun goes through 11-year cycles of solar fluctuations called solar flares that create solar wind. This solar wind creates a vibration that disturbs the electromagnetic field of the earth.

Magnetic North and True North (the Earth’s axis) are not the same. Magnet North moves an average of 40 kilometers every year. In the last 100 years Magnetic North has moved approximately 1200 kilometers. Due to solar flares, Magnetic North is always in constant movement, creating conflicting readings on a compass.

Bagua (eight symbols)

Two diagrams known as bagua (八卦 or pa kua) are important in feng shui. Both predate their mentions in the Yijing (易經), or I Ching. The Lo (River) Chart (Luoshu, or Later Heaven Sequence) and the River Chart (Hetu, or Early Heaven Sequence) are linked to astronomical events of the sixth millennium B.C.E., and with the Turtle Calendar from the time of Yao.[21] The Turtle Calendar of Yao (found in the Yaodian section of the Shangshu or Book of Documents) dates to 2300 B.C.E., plus or minus 250 years.[22]

It seems clear from many sources that time, in the form of astronomy and calendars, is at the heart of feng shui. In Yaodian, the cardinal directions are determined by the marker-stars of the mega-constellations known as the Four Celestial Animals.

East: the Bluegreen Dragon (Spring equinox) --- Niao (Bird), α Hydrae

South: the Red Bird (Summer solstice) --- Huo (Fire), α Scorpionis

West: the White Tiger (Autumn equinox) --- Xu (Emptiness, Void), α, β Aquarii

North: the Dark (Mysterious) Turtle (Winter solstice) --- Mao (Hair), η Tauri (the Pleiades)

The bagua diagrams are also linked with the sifang (four directions) method of divination used during the Shang dynasty.[23] The sifang is much older, however. It was used at Niuheliang, and figured large in the astronomy of the Hongshan culture. This area of China is also linked to Huangdi, the legendary Yellow Emperor, who allegedly invented the south-pointing spoon.[24]

Fundamental Techniques

Schools

There are many 'masters' of the different feng shui schools. However, some maintain that authentic masters impart their genuine knowledge of feng shui only to a few selected students.[25]

Early Fundamentals

Feng shui was being practiced at least 3,500 years before the invention of the magnetic compass,[26] Folk feng shui developed thousands of years ago in small villages of the Orient, whose livelihoods were dependent on it.[27]. Villagers studied the formations of the land and ways of the wind and water to determine the best setting for their survival. Good feng shui would produce bountiful harvests, healthy livestock and abundant life. Harsh winds would destroy their crops, leaving no food for their family or their animals, and level their homes.

The elements, water, rain, wind, fog, and sun were believed to be manifestations of the energy of heaven and earth. Early shaman-kings were believed to have knowledge of landforms and weather, that could be used to drive back the elements that threatened a village. This divination by the study of land forms was the beginning and foundation of feng shui. The use of the compass and magnetic north originated after the use of landform techniques.

In his fieldwork in China, Ole Bruun[28] noted that traditional methods of feng shui (increasingly referred to as "classical feng shui") which are practiced and taught in Asia, all use a compass. Classical feng shui has some features similar to those found in the archaeological record, and in Chinese history and literature, but the application of classical feng shui is not identical to that of ancient feng shui techniques.

Combining Techniques

Classical feng shui is typically associated with the following list of the most common techniques.[29]

- Bagua (relationship of the five phases or wu xing (metal, wood, fire, water, earth)

- Five phases (wuxing relationships)

- Xuan Kong (time and space methods)

- Xuan Kong Fei Xing (Flying Stars methods of time and directions)

- Xuan Kong Da Gua ("Secret Decree" or 64 gua relationships)

- Xuan Kong Shui Fa (time and space water methods)

- Zi Bai (Purple-White Flying Stars methods)

- Ba Zhai (Eight Mansions)

- San Yuan Dragon Gate Eight Formation

- Major & Minor Wandering Stars

- San He Luan Dou (24 Mountains, Mountain-Water relationships)

- San He Shui Fa (water methods)

- Qimen Dunjia (Eight Doors and Nine Stars methods)

- Zi wei dou shu (Purple King, 24-star astrology)

Modern Feng Shui

When the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion broke out in China in 1899, one of the Chinese grievances was that Westerners were violating the basic principles of feng shui in their construction of railroads and other conspicuous public structures throughout China. At that time, Westerners had little knowledge of, or interest in, such Chinese traditions.

Since Richard Nixon visited the People's Republic of China in 1972, there has been substantial interest in the subject of feng shui in the West, and it has been reinvented by New Age entrepreneurs for Western consumption.[30]Ironically, feng shui cannot be legally practiced in the Peoples Republic of China today.

A new version of feng shui was developed in the early 1980s by Thomas Lin Yun Rinpoche, who came to the U.S. from Taiwan. [31] Called Black Sect (or Black Sect Tantric Buddhist, or BTB) feng shui, it relies on "transcendental" methods, the concept of clutter as metaphor for life circumstances, and the use of affirmations or intentions. [32] BTB feng shui has a unique and specially created bagua, with each of the eight compass segment directions representing a particular area of human life.

Shen Dao Feng Shui, developed in the late 1970s by Harrison G. Kyng, became the first school of its type in the United Kingdom. Based upon both 'Form' and 'Compass' styles, Shen Dao utilizes the Five Element modality to assess its clients’ health as well as the harmony of their buildings. This relationship is said to create a unique 'viewpoint' that can then be used to create a greater sense of harmony both inwardly and outwardly. Shen Dao's unique compass uses the former heavenly sequence and expands the Ba Gua into over 300 harmonics that help to fine tune its results.

Criticism

Victorian-era commentators on feng shui were generally ethnocentric, and as such skeptical and derogatory of what little they knew of feng shui.[33] In 1896 at a meeting of the Educational Association of China, Rev. P.W. Pitcher railed at the "rottenness of the whole scheme of Chinese architecture," and urged fellow missionaries "to erect unabashedly Western edifices of several stories and with towering spires in order to destroy nonsense about fung-shuy." [34] Some modern Christians have a similar opinion of feng shui.[35]

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, feng shui has been officially deemed a "feudalistic superstitious practice" and a "social evil" according to the state's atheistic Communist ideology, and has been discouraged or even sometimes banned outright. [36][37]. Persecution was the severest during the Cultural Revolution, when feng shui was classified as a custom under the so-called Four Olds to be wiped out. Feng shui practitioners were beaten and abused by Red Guards, and their works burned. After the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the official attitude became more tolerant, but restrictions on the practice of feng shui are still in place in today's China. It is illegal in the PRC today to register feng shui consultation as a business, and the advertising of feng shui practice is banned. There have been frequent crackdowns on feng shui practitioners on the grounds that they are "promoting feudalistic superstitions," such as one in Qingdao in early 2006, when the city's business and industrial administration office shut down an art gallery converted into a feng shui practice [38]. Communist officials who had consulted feng shui lost their jobs and were expelled from the Communist Party [39].

Partly because of the Cultural Revolution, in today's PRC less than one-third of the population believe in feng shui, and the proportion of believers among young urban PRC Chinese is said to be much less than 5 percent [40]. Among all the ethnic Chinese communities worldwide, the PRC has the least number of feng shui believers in proportion to the general population. Learning feng shui is considered taboo in today's China.[41] Nevertheless, a BBC Chinese news commentary in 2006 reported that feng shui has gained adherents among Communist Party officials. [42], and since the beginning of Chinese economic reforms, the number of feng shui practitioners is increasing. A number of Chinese anthropologists and architects, such as Cao Dafeng, the Vice-President of Fudan University, and Liu Shenghuan of Tongji University, have been permitted to research the subject of feng shui, and to study the history of feng shui or the historical feng shui theories behind the design of heritage buildings.[43], and Liu Shenghuan of Tongji University.

Chinese feng shui practitioners are skeptical of the methods employed and the claims made by Western practitioners. Skeptics in the West dismiss feng shui as "a mystical belief in cosmic harmony"[44] and argue that if feng shui is a science, as some claim, it should feature a consistent methodology. Claims about the alleged benefits of crystals, wind chimes, table fountains, and mirrored balls, on personal life, finances, and relationships are often dismissed as pseudoscience, reliance on the placebo effect, or even outright fraud.

Current Research

A growing body of research exists on what is now called "traditional" or "classical" feng shui.

Landscape ecologists find traditional feng shui an interesting study.[45] In many cases, the only remaining patches of old forest in Asia are "feng shui woods," which strongly suggests the "healthy homes,"[46] sustainability[47] and environmental components of ancient feng shui techniques should not be easily dismissed.[48][49]

Environmental scientists and landscape architects have researched traditional feng shui and its methodologies.[50][51]

Architectural schools study the principles as they applied to ancient vernacular architecture[52][53][54].

Geographers have analyzed the techniques and methods to help locate historical sites in Victoria, Canada,[55] and archaeological sites in the American Southwest, concluding that ancient Native Americans also considered astronomy and landscape features when selecting sites for buildings and ceremonial centers. [56]

Whether collecting data on comparisons to scientific models, or the design and siting of buildings,[57] graduate and undergraduate students have been accumulating solid evidence on what researchers call the "exclusive Chinese cultural achievement and experience in architecture"[58] that is feng shui.

Modern Usage

Architects in Sydney and Hong Kong were surveyed by researchers regarding their selection of the environment for a building and interior layout. The architects generally concurred with the ideal feng shui model.[59]

The hospitality industry has documented the expensive retrofits members have had to undertake when hotel accommodations were not designed with feng shui principles in mind.[60] Donald Trump and Britain's Prince Charles have been accused of using feng shui.[61]

News Corporation consulted feng shui experts regarding the headquarters offices of DirecTV after News Corp. acquired that company in 2003.[62]

See also

- Interior design

- Vastu Shastra

- Environmental psychology

- Environmental metaphysics

- Kau Cim

- Aesthetics

Notes

- ↑ Tina Marie. "What is Feng Shui?" (PaintedFace Publishing, 2007) [1] Feng Shui Facts,org. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Stephen L. Field. The Zhangshu, or Book of Burial. [2]. fengshuigate.com. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Larry Sang. The Principles of Feng Shui. (American Feng Shui Institute, 1995)

- ↑ X. Sun, 2000. "Crossing the Boundaries between Heaven and Man: Astronomy in Ancient China." In H. Selin (ed.), Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy. (Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic), 423-454.

- ↑ Paul Wheatley. The Pivot of the Four Quarters: A preliminary enquiry into the origins and character of the ancient Chinese city. (Aldine Pub. Co., 1971. ISBN 0852241747), 46

- ↑ David W. Pankenier. 'The Cosmo-Political Background of Heaven's Mandate.' Early China 20 (1995): 121-176.

- ↑ Zhentao Xu, David W. Pankenier, and Yaotiao Jiang. East Asian Archaeoastronomy: Historical Records of Astronomical Observations of China, Japan, and Korea. (Earth Space Institute Book Series, Volume 5) (CRC, 2000 ISBN 905699302X), 2

- ↑ Sarah M. Nelson, Rachel A. Matson, Rachel M. Roberts, Chris Rock and Robert E. Stencel. (2006) "Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang." (a paper presented by the Honors class in Archaeoastronomy at the University of Denver in Winter Quarter 2004), 2.

- ↑ Chen Jiujin and Zhang Jingguo, 'Hanshan chutu yupian tuxing shikao,' Wenwu 4 (1989): 15

- ↑ Derek Walters. About the Luopan. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Marc Kalinowski. 'The Xingde Texts from Mawangdui.' Early China. 23-24 (1998-99):125-202.

- ↑ Wallace H. Campbell. Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour Through Magnetic Fields. Academic Press, 2001.

- ↑ Max Knoll. "Transformations of Science in Our Age." In Joseph Campbell (ed.) Man and Time. (Princeton Univ. Press, 1957), 264-306.

- ↑ A.T.Y. Lui, Y. Zheng, Y. Zhang, H. Rème, M.W. Dunlop, G. Gustafsson, S.B. Mende, C. Mouikis, and L.M. Kistler, "Cluster observation of plasma flow reversal in the magnetotail during a substorm." Ann. Geophys. 24 (2006): 2005-2013,

- ↑ Stephen L. Field. 1998.Qimancy, The Art and Science of Fengshui. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ F. R. Moore, 1975. "Influence of solar and geomagnetic stimuli on the migratory orientation of Herring Gull chicks." Auk 92:655-664.

- ↑ F. R. Moore, "Geomagnetic disturbance and the orientation of nocturnally migrating birds." Science 196 (1977): 684-686.

- ↑ Thomas Alerstam, "Bird Migration Across a Strong Magnetic Anomaly." J. exp. Bml. 130 (1987): 63-86

- ↑ L. Pustil’nik, G. Yom Din, "Influence of solar activity on the state of the wheat market in medieval England." Solar Physics 223 (2004): 335–356.

- ↑ L. Pustil’nik, G. Yom Din, "Space climate manifestation in Earth prices – from Medieval England up to Modern U.S.A." Solar Physics 224 (2004): 473–481.

- ↑ Deborah Lynn Porter. From Deluge to Discourse: Myth, History, and the Generation of Chinese Fiction. (S U N Y Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture) (New York: SUNY Press, 1996. ISBN 0791430332), 35-38

- ↑ Xiaochun Sun and Jacob Kistemaker. The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. (Sinica Leidensia, V. 38) (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9004107371), 15-18

- ↑ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Structure in Early China. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000. ISBN 0521624207), 107-128

- ↑ Sarah M. Nelson, Rachel A. Matson, Rachel M. Roberts, Chris Rock, and Robert E. Stencel. Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang.

- ↑ Jacky Cheung Ngam Fung (2007). History of Feng Shui.. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. Cambridge UP: 2000.

- ↑ Candace Czarny.Why Feng Shui?. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ole Bruun. Fengshui in China: Geomantic Divination Between State Orthodoxy and Popular Religion. U of Hawai'i Press, 2003.

- ↑ Cheng Jian Jun and Adriana Fernandes-Gonçalves. Chinese Feng Shui Compass Step by Step Guide. 1998:46-47

- ↑ H. L. Goodall, Jr., "Writing the American Ineffable, or the Mystery and Practice of Feng Shui in Everyday Life." Qualitative Inquiry 7 (1) (2001): 3-20

- ↑ His Holiness Grandmaster Professor Thomas Lin Yun, Yun Lin Temple. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Emily Shao-Fan Wu, 2003. Fengshui plus Buddhism equals what?: an initial analysis of Black Sect Tantric Buddhism in the United States. Thesis (M.A.)—(Boston University, 2003).

- ↑ Andrew L. March. "An Appreciation of Chinese Geomancy." in The Journal of Asian Studies 27 (2) (February 1968): 253-267.

- ↑ Jeffrey W. Cody, "Striking a Harmonious Chord: Foreign Missionaries and Chinese-style Buildings, 1911-1949." Architronic 5:3 (ISSN 1066-6516)

- ↑ Mah, Y.-B. "Living in Harmony with One's Environment: A Christian Response to Feng Shui." Asia J. of Theology 18, Part 2 (2004): 340-361.

- ↑ Chang Liang (pseudonym), 14 January 2005 What Does Superstitious Belief of 'Feng Shui' Among School Students Reveal?. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Tao Shilong, 3 April 2006.The Crooked Evil of 'Feng Shui' Is Corrupting The Minds of Chinese People. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Art Gallery Shut by the Municipality's Business and Industrial Department After Converting to 'Feng Shui' Consultation Office. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Feng Shui Superstitions' Troubles Chinese Authorities, BBC. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Debate on Feng Shui, www.yuce49.com. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Beware of Scams Among the Genuine Feng Shui Practitioners, Sohu.com Inc. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ From Voodoo Dolls to Feng Shui Superstitions, BBC. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Cao Dafeng. FUDAN University. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Monty Vierra. "Harried by "Hellions" in Taiwan." Sceptical Briefs newsletter, March 1997.

- ↑ Bo-Chul Whang and Myung-Woo Lee, "Landscape ecology planning principles in Korean Feng-Shui, Bi-bo woodlands and ponds." J. Landscape and Ecological Engineering 2 (2) (November, 2006): 147-162.

- ↑ Qigao Chen, Ya Feng, Gonglu Wang. "Healthy Buildings Have Existed in China Since Ancient Times." Indoor and Built Environment 6 (3) (1997): 179-187

- ↑ Stephen Siu-Yiu Lau, Renato Garcia, Ying-Qing Ou, Man-Mo Kwok, Ying Zhang, Shao Jie Shen, Hitomi Namba, "Sustainable design in its simplest form: Lessons from the living villages of Fujian rammed earth houses." Structural Survey 2005, 23(5): 371-385

- ↑ Xue Ying Zhuang, Richard T. Corlett, "Forest and Forest Succession in Hong Kong, China." J. of Tropical Ecology 13(6) (Nov., 1997): 857

- ↑ L. M. Marafa, "Integrating Natural and Cultural Heritage: the advantage of feng shui landscape resources." Intl. J. Heritage Studies 9, Part 4 (2003): 307-324

- ↑ B. X. Chen and Y. Nakama, "A summary of research history on Chinese Feng-shui and application of Feng-shui principles to environmental issues." Kyusyu J. For. Res. 57 (2004): 297-301.

- ↑ Jun Xu. A framework for site analysis with emphasis on feng shui and contemporary environmental design principles. (Blacksburg, VA: University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2003)

- ↑ C.-P. Park, N. Furukawa, and M. Yamada, "A Study on the Spatial Composition of Folk Houses and Village in Taiwan for the Geomancy (Feng-Shui)." J. Arch. Institute of Korea 12 (9) (1996): 129-140.

- ↑ P. Xu, "Feng-Shui Models Structured Traditional Beijing Courtyard Houses." J. Architectural and Planning Research 15(4) (1998): 271-282.

- ↑ A. B. Hwangbo, "An Alternative Tradition in Architecture: Conceptions in Feng Shui and Its Continuous Tradition." J. Architectural and Planning Research 19(2) (2002): 110-130.

- ↑ Chuen-Yan David Lai, "A Feng Shui Model as a Location Index." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64 (4): 506–513.

- ↑ P. Xu, "Feng-shui as Clue: Identifying Ancient Indian Landscape Setting Patterns in the American Southwest." Landscape Journal 16 (2) (1997): 174-190.

- ↑ Hui-Chen Lu. 2002. A Comparative analysis between western-based environmental design and feng-shui for housing sites. Thesis (M.S.). California Polytechnic State University, 2002.

- ↑ Su-Ju Lu; Peter Blundell Jones, "House design by surname in Feng Shui." J. of Architecture 5 (4) (December 2000): 355-367.

- ↑ Michael Y. Mak and S. Thomas Ng, "The art and science of Feng Shui—a study on architects’ perception." Building and Environment 40 (3) (March 2005): 427-434

- ↑ J.S. Perry Hobson. International J. of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 6 (6) (Dec 1994): 21-26

- ↑ San Antonio Business Journal, April 7, 2000

- ↑ Claudia Eller, "Younger Wife, Exotic Fish: The Mogul's Secret to Vitality." Los Angeles Times, September 18, 2006

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Simon. Practical feng shui. London: Ward Lock, 1997. ISBN 070637634X

- Bruun, Ole. Fengshui in China: Geomantic Divination Between State Orthodoxy and Popular Religion. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawai'i Press, 2003. ISBN 0824826728

- Field, Stephen L. (translator), The Zangshu, or Book of Burial by Guo Pu (276-324). 2003. online [3]Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- Knapp, Ronald G. China's living houses folk beliefs, symbols, and household ornamentation. Honolulu: University of Hawaiì Press, 1999. ISBN 0585312907

- Pankenier, David W., Zhentao Xu, and Yaotiao Jiang. East Asian Archaeoastronomy: Historical Records of Astronomical Observations of China, Japan and Korea. Amsterdam: Gordon & Breach Science Publishers, 2000. with Vol. 2 forthcoming.

- Rossbach, Sarah. Interior design with feng shui. New York: Penguin/Arkana, 2000. ISBN 0140196080

- Sang, Larry. The Principles of Feng Shui. American Feng Shui Institute, 1995. ISBN 0964458306

- Selin H. (ed.), Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic/Springer, 2001. ISBN 0792363639

- Wang, Aihe. Cosmology and Political Structure in Early China. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000. ISBN 0521624207

- Wheatley, Paul. The Pivot of the Four QuartersA preliminary enquiry into the origins and character of the ancient Chinese city. Aldine Pub. Co., 1971. ISBN 0852241747

- Wu, Baolin. Lighting the Eye of the Dragon: Inner Secrets of Taoist Feng Shui. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000. ISBN 0312254970

- Yoon, Hong-key. Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy. Lexington Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0739113486

- Zhang, Juwen. A Translation of the Ancient Chinese 'The Book of Burial (Zang Shu)' by Guo Pu (276-324). Lewiston, NY: Edward Mellen Press, 2004. ISBN 0773463526

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.