Alvin Langdon Coburn

| Alvin Langdon Coburn | |

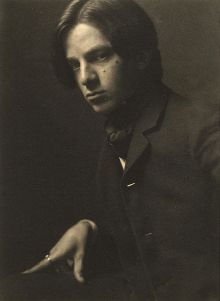

Self-portrait, 1905 | |

| Born | June 11 1882 Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died | November 23 1966 (aged 84) Rhos-on-Sea, Colwyn Bay, Wales |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Photography |

Alvin Langdon Coburn (June 11, 1882 ‚Äď November 23, 1966) was an early twentieth century photographer who became a key figure in the development of American pictorialism. He became the first major photographer to emphasize the visual potential of elevated viewpoints by taking photographs from the tops of tall buildings, emphasizing a flattened perspective and geometric patterning. He was also renowned for his portraits of celebrities like George Bernard Shaw, Henry James, and William Butler Yeats.

Coburn invented a kaleidoscope-like instrument that Ezra Pound dubbed a "Vortoscope," and the resulting photographs "Vortographs." His Vortographs are now widely celebrated as the first consciously created abstract photographs. Despite his success and fame as an innovative photographer, Coburn's interest turned to the spiritual side of life, with investigations of mysticism and the occult, which occupied that later part of his life.

Life

Alvin Langdon Coburn was born on June 11, 1882, at 134 East Springfield Street in Boston, Massachusetts, to a middle-class family. His father, who had established the successful firm of Coburn & Whitman Shirts, died when he was seven. After that he was raised solely by his mother, Fannie, who remained the primary influence in his early life, even though she remarried when he was a teenager. In his autobiography, Coburn wrote, "My mother was a remarkable woman of very strong character who tried to dominate my life…It was a battle royal all the days of our life together."[1]

In 1890, the family visited his maternal uncles in Los Angeles, and they gave him a 4 x 5 Kodak camera. He immediately fell in love with the camera, and within a few years he had developed a remarkable talent for both visual composition and technical proficiency in the darkroom. When he was sixteen years old, in 1898, he met his cousin F. Holland Day, who was already an internationally known photographer with considerable influence. Day recognized Coburn’s talent and mentored him, encouraging him to take up photography as a career.

At the end of 1899, he and his mother moved to London, where they met up with Day. Day had been invited by the Royal Photographic Society to select prints from the best American photographers for an exhibition in London. He brought more than one hundred photographs with him, including nine by Coburn ‚Äď who at this time was only 17 years old. As a result, Coburn‚Äôs career took a giant first step.

In 1901, Coburn lived in Paris for a few months to study with photographer Edward Steichen and Robert Demachy. He and his mother then toured France, Switzerland, and Germany for the remainder of the year.

When they returned to America in 1902, Coburn began studying with famed photographer Gertrude Kasebier in New York. He opened a photography studio on Fifth Avenue but spent much of his time that year studying with Arthur Wesley Dow at his School of Art in Massachusetts. It was here that he received his real grounding in composition which was the underpinning of his future work. At the same time, his mother continued to promote her son whenever she could. Alfred Stieglitz once told an interviewer, "Fannie Coburn devoted much energy trying to convince both Day and me that Alvin was a greater photographer than Steichen."[2]

Coburn returned to America in 1910. While in New York, he met and married Edith Wightman Clement of Boston, on October 11, 1912. In November, Coburn and his wife returned to England, and after twenty-three trans-Atlantic crosses he never again returned to the United States.[3]

In 1916, Coburn met George Davison, a fellow photographer and a philanthropist who was involved in Theosophy and Freemasonry. This started him on a path of studying mysticism, metaphysical ideals, and Druidism. Eventually he would devote most of his life to these studies, foregoing photography as his primary interest.

In 1928 Coburn's mother died. Her passing was a sign that his new devotion to religious interests was the right course for him.

After living in England for more than twenty years, Coburn finally became a British subject in 1932.

In 1945 he moved from his house in Harlech, North Wales to Rhos-on-Sea, Colwyn Bay, on the north coast of Wales. He lived there the rest of his life. His wife Edith died on October 11, 1957, their forty-fifth wedding anniversary.

Coburn died in his home in North Wales on November 23, 1966, aged 84.

Career

Rise to fame (1900-1905)

Coburn’s prints at the Royal Photographic Society exhibition when he was only 17 years old attracted the attention of another important photographer, Frederick H. Evans. Evans was one of the founders of the Linked Ring, an association of artistic photographers that was considered to be the highest authority for photographic aesthetics. In the summer of 1900 Coburn was invited to exhibit with them, which elevated him to the ranks of some of the most elite photographers of the day. In 1903, Coburn was elected as an Associate of the Linked Ring, making him one of the youngest members of that group and one of only a few Americans so honored.

In May 1903 he gave his first one-man show at the Camera Club of New York, and in July Stieglitz published one of his gravures in Camera Work, No. 3.

In 1904, Coburn returned to London with a commission from The Metropolitan Magazine to photograph England’s leading artists and writers, including G.K. Chesterton, George Meredith, and H.G. Wells. During this trip he visited renowned pictorialist J. Craig Annan in Edinburgh, and made studies of motifs photographed by pioneering photographers Hill and Adamson.[3] Six more of his images were published in Camera Work, No. 6 (April, 1904). In 1905 he photographed American artist Leon Dabo.

Coburn remained in London throughout 1905 and much of 1906, taking both portraits and landscapes around England. He photographed Henry James for The Century magazine and returned to Edinburgh for a series he intended to be visualizations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes.

Symbolist period (1906-1912)

The years 1906-1907 were some of the most prolific and important for Coburn. He began 1906 by having one-man shows at the Royal Photographic Society (accompanied by a catalog with a preface by George Bernard Shaw) and at the Liverpool Amateur Photographic Association. In July, five more gravures were published in Camera Work (No. 15). At the same time he began to study photogravure printing at the London County Council School of Photo-Engraving. It was during this time that Coburn made one of his most famous portraits, that of George Bernard Shaw posing nude as Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker.

In the summer, he cruised round the Mediterranean and traveled to Paris, Rome, and Venice in the fall while working on frontispieces for an American edition of Henry James’ novels. While in Paris he saw Steichen’s Autochrome color prints and learned the process from him.

By 1907, Coburn was so well established in his career that Shaw called him "the greatest photographer in the world," although he was only 24 years old at the time.[4] He continued his success by having a one-man show at Stieglitz‚Äôs prestigious Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession in New York City and by organizing an international exhibition of photography at the New English Art Galleries in London. At the request of American art collector Charles Lang Freer, Coburn briefly returned to the U.S. so he could photograph Freer‚Äôs large collection of oriental art and Whistler prints. Coburn became captivated with the ‚Äúexotic‚ÄĚ style of the oriental artists and it began to have an influence on both his thinking and his photography.

In January 1908, twelve more of Coburn’s photographs were published in Camera Work (No. 21). Oddly, in the same issue there was an anonymous article that leveled some harsh words at him:

Coburn has been a favored child throughout his career… No other photographer has been so extensively exploited nor so generally eulogized. He enjoys it all; is amused at the conflicting opinions about him and his work, and, like all strong individuals, is conscious that he knows best what he wants and what he is driving at. Being talked about is his only recreation."[5]

The author was probably Stieglitz, who sometimes delighted in both promoting and castigating a photographer, especially if he felt the person was becoming too conceited. The criticism did not seem to have a long-term affect on their relationship, as both continued to be close colleagues for many years.

In the spring, Coburn held another one-man show, this time at the Goupil Galleries in New York. Soon after he wrote to Stieglitz, "Printing almost entirely in gray now... think it a reaction from the autochromes."[3] In the summer he visited Dublin, where he made portraits of W.B. Yeats and George Moore. He continued his travels that year with trips to Bavaria and Holland.

The next year, Stieglitz gave Coburn his second one-man exhibition at his gallery, which by that time had come to be known only as "291." Another sign of Coburn‚Äôs prominence at that time was that Stieglitz had given two shows to only one other photographer ‚Äď Edward Steichen. Back in London, Coburn bought a new home with a large studio area where he set up two printing presses. He proceeded to use the skills he had learned at the County Council School to publish a book of his own photographs called London.

Coburn returned to America in 1910, exhibiting 26 prints at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. He began traveling extensively in the U.S. for the next year, going to Arizona to photograph the Grand Canyon and to California to take photos in Yosemite National Park. He came back to New York in 1912 and took a series of new photos which he published in his book New York. It was during this period that he made some of his most famous photographs from elevated viewpoints, including his best known image The Octopus.

Explorations (1913-1923)

Coburn continued to build his fame by publishing what would become his most famous book, Men of Mark, in 1913. The book featured 33 gravure prints of important European and American authors, artists, and statesmen, including Henri Matisse, Henry James, Auguste Rodin, Mark Twain, Theodore Roosevelt, and Yeats. In the preface to the book, he wrote:

To make satisfactory photographs of persons it is necessary for me to like them, to admire them, or at least to be interested in them. It is rather curious and difficult to exactly explain, but if I dislike my subject it is sure to come out in the resulting portrait. I had thought of using Men of Genius as the title for this book, but Arnold Bennett objected seriously, saying, very modestly, that he did not consider himself a man of genius, but merely a working author, and absolutely refusing to join the throng unless I changed it, so I told him that if he would give me a better one I would use it. Men of Mark is his alternative.[6]

In 1915, Coburn organized the exhibition "Old Masters of Photography," shown at the Royal Photographic Society in London and at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in the U.S. The show included many historical prints from Coburn’s own collection.

The following year two pivotal events occurred in his life. First, he met George Davison, a fellow photographer and a philanthropist who was involved in Theosophy and Freemasonry. He also met Ezra Pound, who introduced him to the short-lived Vorticism movement in Britain. These new visual aesthetics intrigued Coburn and, provoked by his growing spiritual quest, he began to re-examine his photographic style. He created with a bold and distinctive portrait of Pound, showing three over-lapping images of differing sizes. Within a brief period he moved from this semi-representative image to a series of abstract images that are among the first completely non-representative photographs ever made.

Coburn invented a kaleidoscope-like instrument with three mirrors clamped together, which when fitted over the lens of the camera would reflect and fracture the image. It would come to be called a "Vortoscope" by Pound, and the resulting photographs "Vortographs."[7] He made only about 18 different Vortographs, taken over a period of just one month, yet they remain among the most striking images in early twentieth century photography.

In 1917 he had a show of Vortographs and paintings at the Camera Club in London. He had recently started painting in what Ezra Pound called Post-Impressionist style, and the combination of these 'second-rate' paintings along with his highly unusual photographs received mixed reviews. Stieglitz in particular did not like the change in Coburn’s imagery, and he rejected several prints for a show he was putting together.

From 1919 to 1921 Coburn became increasingly involved with the Freemasons, achieving the title of Royal Arch Mason. He also joined the Societas Rosicruciana and delved further into metaphysical studies.

In 1922 Coburn briefly returned to his roots when he published More Men of Mark, a second book of portraits he had taken more than ten years earlier.[8] This volume included previously unpublished photographs that included Pound, Thomas Hardy, Frank Harris, Joseph Conrad, Israel Zangwill, and Edmund Dulac.

Spiritual devotion (1923-1930)

In 1923, Coburn became involved with the comparative religious group that began as the Hermetic Truth Society and the Order of Ancient Wisdom, which, according to their quarterly magazine The Shrine of Wisdom, were devoted to "Synthetic Philosophy, Religion and Mysticism."[9] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Coburn enmeshed himself in the beliefs of the Universal Order, His deep interest in mysticism, and especially Freemasonry, was to occupy the greatest part of the remainder of his life.

Coburn did much research into the history of freemasonry, as well as on aspects of the occult and mysticism. He presented numerous lectures based on his findings to Masonic gatherings, traveling extensively throughout England and Wales. He also took a particular interest in the ceremonial rituals and rites performed, and in their origins and symbolism.

In 1927, Coburn was made an honorary Ovate of the Welsh Gorsedd, or Council of Druids, and he took the Welsh name "Maby-y-Trioedd" (Son of the Triads).

Later life (1931-1966)

By 1930 Coburn had lost almost all interest in photography. He decided that his past was of little use to him now, and over the summer he destroyed nearly 15,000 glass and film negatives ‚Äď nearly his entire life‚Äôs output. That same year he donated his extensive collection of contemporary and historical photographs to the Royal Photographic Society.

A year later he wrote his last letter to Stieglitz, and from then on he made only a few new photographs. Ironically, just when he was making an almost complete break from photography Coburn was elected Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society.

Legacy

Alvin Langdon Coburn was one of the most celebrated photographers of his generation, an important member of key photographic groups on both sides of the Atlantic. His portraits of celebrities like George Bernard Shaw, Henry James, and William Butler Yeats received wide acclaim.

He was the first major photographer to emphasize the visual potential of elevated viewpoints, taking photographs from the tops of tall buildings. This angle emphasized a flattened perspective and geometric patterning.

Coburn became a key figure in the development of American pictorialism, a style and aesthetic movement that dominated photography during the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing, or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer's realm of imagination. This is achieved by the photographer manipulating what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of "creating" an image rather than simply recording it.[10]

Coburn invented a kaleidoscope-like instrument, named by Ezra Pound the "Vortoscope." When Coburn exhibited 18 of the resulting photographs, called "Vortographs," in London in 1917, they created a sensation and were debated in the press for several months. They are now widely celebrated as the first consciously created abstract photographs.

Despite his success and fame as an innovative photographer, Coburn's interest turned to the spiritual side of life, with investigations of mysticism and the occult. Coburn explained why he had given up his early dedication to photography:

I think I can justify this change of occupation on the ground of ultimate values. If you compare photography and religious mysticism as alternatives to which one should devote one’s life, can there be any doubt as to their respective importance?[1]

Gallery

George Meredith (1911)

Bernard Shaw (1908)

Rodin (1908)

Henri Matisse (1913)

Theodore Roosevelt (1907; printed 1913)

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 Alvin Langdon Coburn, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Photographer, An Autobiography (Dover Publications, 1966).

- ‚ÜĎ Margaret F. Harker, The Linked Ring: The Secession Movement in Photography in Britain 1892-1910 (London: Heinemann, 1979, ISBN 978-0434313600).

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weston J. Naef, The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978, ISBN 978-0670670512}.

- ‚ÜĎ Mike Weaver, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Symbolist Photographer (New York: Aperture, 1986, ISBN 978-0893812409).

- ‚ÜĎ Alfred Stieglitz (ed.), Camera Work 21 (January, 1908): 30.

- ‚ÜĎ Alvin Langdon Coburn, Men of Mark (London: Duckworth & Co., 1913).

- ‚ÜĎ Hanako Murata, Vortograph Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ‚ÜĎ Alvin Langdon Coburn, More Men of Mark (London: Duckworth & Co., 1922).

- ‚ÜĎ Steven J. Sutcliffe, Children of the New Age: A History of Spiritual Practices (New York: Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-0415242998).

- ‚ÜĎ Patrick Daum, (ed.), Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888‚Äď1918 (Merrell Publishers, 2006, ISBN 978-1858943312).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coburn, Alvin Langdon. Men of Mark. London: Duckworth & Co., 1913.

- Coburn, Alvin Langdon. More Men of Mark. London: Duckworth & Co., 1922.

- Coburn, Alvin Langdon. Alvin Langdon Coburn, Photographer, An Autobiography. Dover Publications, 1978. ISBN 978-0486236858

- Daum, Patrick (ed.). Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888‚Äď1918. Merrell Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1858943312

- Harker, Margaret F. The Linked Ring: The Secession Movement in Photography in Britain 1892-1910. London: Heinemann, 1979. ISBN 978-0434313600

- Naef, Weston J. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978. ISBN 978-0670670512

- Sutcliffe, Steven J. Children of the New Age: A History of Spiritual Practices. New York: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-0415242998

- Weaver, Mike. Alvin Langdon Coburn, Symbolist Photographer. New York: Aperture, 1986. ISBN 978-0893812409

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Alvin Langdon Coburn Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center.

- Alvin Langdon Coburn Masters of Photography.

- The Vorticists: Rebel Artists in London and New York, 1914-18

- Alvin Langdon Coburn by John A Benigno.

- Alvin Langdon Coburn Museum of Modern Art

- Alvin Langdon Coburn The J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Pictorialism in America Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The MET.

- Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882-1966 ‚Äď Iconic Photographer Amateur Photographer.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.