Alfred Stieglitz

| Alfred Stieglitz | |

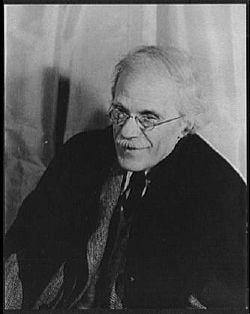

Alfred Stieglitz, photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1935.

| |

| Born | January 1, 1864 Hoboken, New Jersey, USA |

|---|---|

| Died | July 13, 1946 |

Alfred Stieglitz (January 1, 1864 ‚Äď July 13, 1946) was an American photographer whose ground-breaking technical advances and attention to principles of composition and design were instrumental in advancing photography as a modern visual art. Over his 50-year career, Stieglitz helped to transform photography from a technology for visual reproduction into an expressive art form like painting, sculpture, and graphic arts. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz served as coeditor of American Amateur Photography (1893-1896) and later as editor of Camera Notes, both of which publicized the works of leading photographers and discussed theoretical, technical, and aesthetic aspects of modern photography.

Stieglitz lived during the transition from a predominantly agricultural to industrial society and played a singular role in the emergence of modernism in the visual arts. Photography as a technology was uniquely suited to examine the deracination of modern industrial life, a theme taken up in much modernist literature and art.

Stieglitz also played a significant part in introducing modern art to United States. Married to the noted modernist painter Georgia O'Keeffe, Stieglitz with O'Keeffe owned a series of galleries that brought modernist works before the public. Stieglitz's achievement as an artist was assessed by photographer Edward Steichen as "like none ever made by any other photographer," and his influence on artists, writers, and art institutions encouraged a new estimation of America's contribution to the arts and culture.

Early Life

Alfred Stieglitz was born the eldest of six children in Hoboken, New Jersey to German-Jewish immigrant parents. When Stieglitz was 16, the family moved to a brownstone on Manhattan's Upper East Side. The Stieglitz household was a lively place, often filled with artists, writers, musicians and creative thinkers. This may have influenced Stieglitz's later sensitivity toward the needs of struggling artists and his desire to support and provide opportunities for them to show their work.

The parents argued frequently over money for domestic expenses, even though there was plenty for an array of luxuries. This conflict and inconsistency influenced Stieglitz to choose a simpler way and to minimize the profit aspect of his business enterprises later in life. Stieglitz was an indifferent student but had strong manual dexterity as well as a determination to learn new skills, which served him well later as he worked patiently to master photographic skills and techniques.

His father retired from business suddenly and moved the family to Germany in 1881 to take advantage of educational and cultural opportunities in Europe. The next year, Stieglitz began studying mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin. He had little enjoyment in his coursework and spent free time immersed in the cultural scene of theater, operas, and concerts. The following year, an impulse purchase of a camera was life changing for him and he soon devoted himself in the study of photography.

Stieglitz set up a makeshift darkroom and set about experimenting. He took coursework from world-renowned Dr. Hermann Wilhem Vogel on the science and chemistry of photography in a state-of-the-art laboratory. He dedicated himself to experimentation for the sake of his art, which came to influence other aspects of his life. Eventually he referred to his various galleries as his laboratories.

Traveling through the European countryside on foot or bike with his camera during the summer of 1883, Stieglitz took many photographs of peasants working on the Dutch seacoast and of undisturbed nature scenes in Germany's Black Forest.

His photographs won prizes and attention throughout Europe in the 1880s; he received more than 150 awards during this time, which led to appointments on judging panels for exhibits. He began to write on technical problems for photographic publications as well. Meanwhile he continued to hone his technique in photos of cityscapes and architectural views on platinum paper with its velvet-like surface and subtle changes of tone. His persistent experimentation and testing of accepted rules of photography brought about revolutionary advances in photographic technique. At the Berlin Jubilee Exhibition in 1889, Stieglitz demonstrated that a photo could be exposed, developed and printed in a record time of 37 minutes. This had extraordinary impact on photo journalism.

Return to America

Stieglitz's parents had returned to America in 1886. In his independence, Stieglitz became involved in more than one unstable romance, and his father, who was still supporting his son, made it clear that it was time for Alfred to return to New York, embark on a career and find a suitable wife.

Stieglitz married Emmeline Obermeyer in 1893 after his return to New York. They had a daughter, Kitty, in 1898 and support from Emmeline's father and his own enabled Stieglitz the financial freedom to pursue his photography.

From 1893 to 1896, Stieglitz was editor of American Amateur Photographer magazine. However, his editorial style proved to be brusque and autocratic, alienating many subscribers. After being forced to resign, Stieglitz turned to the New York Camera Club (later renamed The Camera Club of New York, still in existence). He retooled their newsletter into a serious art periodical, announcing that every published image would be a picture, not a photograph.

The art of photography

Big camera clubs that were the vogue in America at the time did not satisfy him. In 1902 he organized an invitation-only group, which he dubbed the Photo-Secession. The purpose of the group was to persuade the art world to recognize photography "as a distinctive medium of individual expression." Among its members were Edward Steichen, Gertrude Kasebier, Clarence Hudson White and Alvin Langdon Coburn. Steichen and Stieglitz, who first met in 1900, were to become partners in efforts to introduce modern art to America.

Photo-Secession held its own exhibitions and published Camera Work, a preeminent quarterly photographic journal, until 1917, with Stieglitz serving as editor. Camera Work fulfilled Stieglitz' vision for the magazine as the premiere art publication for the avant garde and art connoisseur. The journal also served as a record of Stieglitz' introduction of modern art to America.

From 1905 to 1917, Stieglitz managed the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue (which came to be known as 291). Artists and photographers shown at 291 included Pablo Picasso, Cezanne, Matisse, Brancusi, Rodin, John Marin, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. Because of his time in Paris immersed in the art scene, Edward Steichen was instrumental in meeting many of these artists and introducing their work for the first time in America.

Photographer Paul Haviland arrived at 291 in 1908. Stieglitz and Steichen were discussing closing the gallery due to Stieglitz' constant fatigue and the increased expenses required to keep it open. Haviland, a French-born descendant of wealth, was inspired by a Rodin exhibit at the gallery and offered patronage to continue the operation. Stieglitz, always proud, resisted at first but was coaxed by Steichen, the playwright George Bernard Shaw and other colleagues to accept Haviland's help and continue the endeavor. Haviland became a strong partner, helping to facilitate art exhibits and learning more about photography from Stieglitz.

In 1910, Stieglitz was invited to organize a show at Buffalo's Albright-Knox Art Gallery, which set attendance records. He was insistent that "photographs look like photographs," so that the medium of photography would be judged according to its own aesthetic credo, separating photography from other fine arts such as painting, and defining photography as a fine art for the first time. This approach to photography was termed "straight photography" in contrast to other forms of photography, specifically "pictorial photography" which practiced manipulation of the image either before or after exposure, often to mimic the effects of painting, theater, or sculpture.

Marriage to Georgia O'Keeffe

Stieglitz began to exhibit the works of the modernist artist Georgia O'Keeffe at 291 in 1916 and 1917. Stieglitz began photographing O'Keeffe in 1916, which led to a rupture with his wife. Reportedly she threw him out of their house after coming home to find him photographing O'Keeffe. The couple divorced in 1918, and shortly after, Stieglitz moved in with O'Keeffe.

The two married in 1924, and over the next two decades he compiled one of his greatest works, his collective portrait of O'Keeffe (over 300 images), which was a creative collaboration between sitter and photographer, on the theme of "womanhood" which show her systematically undressing.

Eventually, the marriage between O'Keeffe and Stieglitz became strained as her role became increasingly a caregiver due to his prevailing heart condition and his hypochondria. Following a visit to Santa Fe and Taos in 1929, O'Keeffe began to spend a portion of most summers in New Mexico.

Later years

In the 1930s, Stieglitz took a series of photographs, some nude, of heiress Dorothy Norman. This caused additional strain in the marriage, their relationship increasingly alternating between conflict and reconciliation, and, eventually, acceptance and affection.

In these years, Stieglitz also presided over two non-commercial New York City galleries, The Intimate Gallery and An American Place. At the latter he forged a friendship with the great twentieth century photographer Ansel Adams. Adams displayed many prints in Stieglitz's gallery, corresponded with him and photographed Stieglitz on occasion. Stieglitz was a great philanthropist and sympathizer with his fellow human beings, once memorably interrupting a visit from Adams to receive and provide support for a disheveled artist.

Stieglitz stopped photographing in 1937 due to heart disease. Over the last ten years of his life, he summered at Lake George, New York, working in a shed he had converted into a darkroom. O'Keeffe and Stieglitz wintered in Manhattan. He died in 1946 at 82, still a staunch supporter of O'Keeffe and she of him.

Legacy

By utilizing a technological medium to represent an artistic vision, Alfred Stieglitz documented the ascendancy of industry, the growth of urbanization, changes in social mores, and the emergence of a modern commercial culture. Like the expatriates Henry James, T. S. Eliot, and Ezra Pound, Stieglitz sought to authenticate American experience informed by European aesthetic traditions, thus encouraging greater acceptance of American artistic perspectives in Europe. As a photographer, Stieglitz was primarily interested in the capacity of the photograph to express a coherent artistic statement, while advocating modernist art as a unique medium to explore contemporary modern life. According to cultural historian Bram Dijkstra, Stieglitz "provided the essential example of the means by which the artist could reach out to a new, more accurate mode of representing the world of experience."

Pictures by Stieglitz:

- The Last Joke‚ÄĒBellagio (1887); gathering of children in a photograph praised for its spontaneity, won first prize in The Amateur Photographer that year)

- Sun Rays‚ÄĒPaula, Berlin (1889); a young woman writes a letter lit by sunlight filtered through Venetian blinds)

- Spring Showers (1900-1901)

- The Hand of Man (1902); a train pulling into the Long Island freight yard)

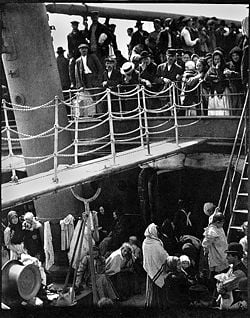

- The Steerage (photographed in 1907 but unpublished until 1911); famous photograph of working class people crowding two decks of a transatlantic steamer)

- The Hay Wagon (1922)

- Equivalent (1931); a picture of clouds taken as pure pattern)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Masters: Alfred Steiglitz, [1].Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved March 25, 2008

- Davis, Keith F., An American Century of Photography, Kansas City: Hallmark Cards. ISBN 810963787

- Eisler, Benita. 1991. O'Keeffe and Stieglitz an American romance. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0385261225

- Hoffman, Katherine. 2004. Stieglitz A Beginning Light. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300102399

- Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977. ISBN 9780374226268

- Weber, Eva. 1994. Alfred Stieglitz. New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 051710332X

- Whelan, Richard. 1995. Alfred Stieglitz a biography. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316934046

External links

All links retrieved July 20, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.