Difference between revisions of "Water fluoridation" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{credits|Water_fluoridation|262024854}} |

Revision as of 17:55, 6 January 2009

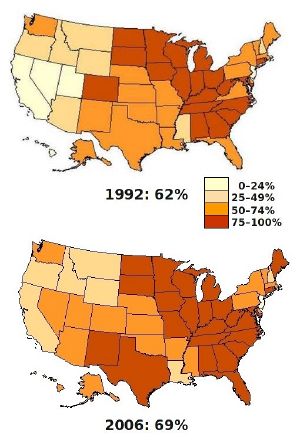

Water fluoridation is the controlled addition of fluoride to a public water supply in order to reduce tooth decay.[1] Its use in the U.S. began in the 1940s, following studies of children in a region where water is naturally fluoridated. Too much fluoridation causes dental fluorosis, which mottles or stains teeth, but U.S. researchers discovered that moderate fluoridation prevents cavities, and it is now used for about two-thirds of the U.S. population on public water systems[2] and for about 5.7% of people worldwide.[3] Although there is no clear evidence of adverse effects other than fluorosis, most of which is mild and not of aesthetic concern,[4][5] water fluoridation has been contentious for ethical, safety, and efficacy reasons,[3] and opposition to water fluoridation exists despite its support by public health organizations.[6]

Motivation

Water fluoridation's goal is to prevent tooth decay (dental caries), one of the most prevalent chronic diseases worldwide, and one which greatly affects the quality of life of children, particularly those of low socioeconomic status. Fluoride toothpaste, dental sealants, and other techniques are also effective in preventing tooth decay;[7] water fluoridation, when it is culturally acceptable and techically feasible, has substantial advantages over toothpaste, especially for subgroups at high risk.[8]

Implementation

Fluoridation is normally accomplished by adding one of three compounds to drinking water:

- Hydrofluosilicic acid (H2SiF6; also known as hexafluorosilicic, hexafluosilicic, silicofluoric, or fluosilicic acid), is an inexpensive watery byproduct of phosphate fertilizer manufacture.[9]

- Sodium silicofluoride (Na2SiF6) is a powder that is easier to ship than hydrofluosilicic acid.[9]

- Sodium fluoride (NaF), the first compound used, is the reference standard.[9] It is more expensive, but is easily handled and is used by smaller utility companies.[10]

These compounds were chosen for their solubility, safety, availability, and low cost.[9] The estimated cost of fluoridation in the U.S., in 1999 dollars, is $0.72 per person per year (range: $0.17–$7.62); larger water systems have lower per capita cost, and the cost is also affected by the number of fluoride injection points in the water system, the type of feeder and monitoring equipment, the fluoride chemical and its transportation and storage, and water plant personnel expertise.[1] A 1992 census found that, for U.S. public water supply systems reporting the type of compound used, 63% of the population received water fluoridated with hydrofluosilicic acid, 28% with sodium silicofluoride, and 9% with sodium fluoride.[11]

Defluoridation is needed when the naturally occuring fluoride level exceeds recommended limits. It can be accomplished by percolating water through granular beds of activated alumina, bone meal, bone char, or tricalcium phosphate; by coagulation with alum; or by precipitation with lime.[12]

In the U.S. the optimal level of fluoridation ranges from 0.7 to 1.2 mg/L (milligrams per liter, equivalent to parts per million), depending on the average maximum daily air temperature; the optimal level is lower in warmer climates, where people drink more water, and is higher in cooler climates.[13] In Australia optimal levels range from 0.6 to 1.1 mg/L.[5] Some water is naturally fluoridated at optimal levels, and requires neither fluoridation nor defluoridation.[12]

Mechanism

Water fluoridation operates by creating low levels (about 0.04 mg/L) of fluoride in saliva and plaque fluid. This in turn reduces the rate of tooth enamel demineralization, and increases the rate of remineralization of the early stages of cavities.[14] Fluoride is the only agent that has a strong effect on cavities; technically, it does not prevent cavities but rather controls the rate at which they develop.[15]

Evidence basis

Existing evidence strongly suggests that water fluoridation prevents tooth decay. There is also consistent evidence that it causes fluorosis, most of which is mild and not considered to be of aesthetic concern.[5] The best available evidence shows no association with other adverse effects. However, the quality of the research on fluoridation has been generally low.[4]

Effectiveness

Water fluoridation is the most effective and socially equitable way to achieve wide exposure to fluoride's cavity-prevention effects,[5] and has contributed to dental health worldwide of children and adults.[1] A 2000 systematic review found that fluoridation was associated with a decreased proportion of children with cavities (the median of mean decreases was 14.6%, the range −5% to 64%), and with a decrease in decayed, missing, and filled primary teeth (the median of mean decreases was 2.25 teeth, the range 0.5 to 4.4 teeth). The evidence was of moderate quality. Many studies did not attempt to reduce observer bias, control for confounding factors, or use appropriate analysis.[4] Fluoridation also prevents cavities in adults of all ages;[16] a 2007 meta-analysis found that fluoridation prevented an estimated 27% of cavities in adults (range 19%–34%).[17]

The decline in tooth decay in the U.S. since water fluoridation began in the 1950s has been attributed largely to the fluoridation,[13] and has been listed as one of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century in the U.S.[18] Initial studies showed that water fluoridation led to reductions of 50%–60% in childhood cavities; more recent estimates are lower (18%–40%), likely due to increasing use of fluoride from other sources, notably toothpaste.[1] The introduction of fluoride toothpaste in the early 1970s has been the main reason for the decline in tooth decay since then in industrialized countries.[14]

In Europe, most countries have experienced substantial declines in cavities without the use of water fluoridation, indicating that water fluoridation may be unnecessary in industrialized countries.[14] For example, in Finland and Germany, tooth decay rates remained stable or continued to decline after water fluoridation stopped. Fluoridation may be more justified in the U.S. because unlike most European countries, the U.S. does not have school-based dental care, many children do not attend a dentist regularly, and for many U.S. children water fluoridation is the prime source of exposure to fluoride.[19]

Although a 1989 workshop on cost effectiveness of caries prevention concluded that water fluoridation is one of the few public health measures that saves more money than it costs, little high-quality research has been done on the cost-effectiveness and solid data are scarce.[1][13]

Safety

At the commonly recommended dosage, the only clear adverse effect is dental fluorosis, most of which is mild and not considered to be of aesthetic concern. Compared to unfluoridated water, fluoridation to 1 mg/L is estimated to cause fluorosis in one of every 6 people, and to cause fluorosis of aesthetic concern in one of every 22 people.[4] Fluoridation has little effect on risk of bone fracture (broken bones); it may result in slightly lower fracture risk than either excessively high levels of fluoridation or no fluoridation.[5] There is no clear association between fluoridation and cancer, deaths due to cancer, bone cancer, or osteosarcoma.[5]

In rare cases improper implementation of water fluoridation can result in overfluoridation, resulting in fluoride poisoning. For example, in Hooper Bay, Alaska in 1992, a combination of equipment and human errors resulted in one of the two village wells being overfluoridated, causing one death and an estimated 295 nonfatal cases of fluoride intoxication.[20]

Adverse effects that lack sufficient evidence to reach a scientific conclusion[5] include:

- Like other common water additives such as chlorine, hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride decrease pH, and cause a small increase of corrosivity; this can easily be resolved by adjusting the pH upward.[21]

- Some reports have linked hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride to increased human lead uptake;[22] these have been criticized as providing no credible evidence.[21]

- Arsenic and lead may be present in fluoride compounds added to water, but there is no credible evidence that this is of concern: concentrations are below measurement limits.[21]

The effect of water fluoridation on the environment has been investigated, and no adverse effects have been established. Issues studied have included fluoride concentrations in groundwater and downstream rivers; lawns, gardens, and plants; consumption of plants grown in fluoridated water; air emissions; and equipment noise.[21]

Politics

Almost all major health and dental organizations support water fluoridation, or have found no association between fluoridation and adverse effects.[6][23] These organizations include the World Health Organization,[24] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[1] the U.S. Surgeon General,[25] and the American Dental Association.[26]

Despite support by public health organizations and authorities, efforts to introduce water fluoridation meet considerable opposition whenever it is proposed.[6] Controversies include disputes over fluoridation's benefits and the strength of the evidence basis for these benefits, the difficulty of identifying harms, legal issues over whether water fluoridation is a medicine, and the ethics of mass intervention.[3] Opposition campaigns involve newspaper articles, talk radio, and public forums. Media reporters are often poorly equipped to explain the scientific issues, and are motivated to present controversy regardless of the underlying scientific merits. Internet websites, which are increasingly used by the public for health information, contain a wide range of material about fluoridation ranging from factual to fraudulent, with a disproportionate percentage opposed to fluoridation. Conspiracy theories involving fluoridation are common, and include claims that fluoridation is part of a Communist or New World Order plot to take over the world, that it was pioneered by a German chemical company to make people submissive to those in power, that it is backed by the sugar or aluminum or phosphate industries, or that it is a smokescreen to cover failure to provide dental care to the poor.[6] Specific antifluoridation arguments change to match the spirit of the time.[27]

Use around the world

About 5.7% of people worldwide drink fluoridated water;[3] this includes 61.5% of the U.S. population.[29] 12 million people in Western Europe have fluoridated water, mainly in England, Spain, and Ireland. France, Germany, and some other European countries use fluoridated salt instead; the Netherlands, Sweden, and a few other European countries rely on fluoride supplements and other measures.[30] The justification for water fluoridation is analogous to the use of iodized salt for the prevention of goiters. China, Japan, the Philippines, and India do not fluoridate water.[31]

Australia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Canada, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, Israel, Malaysia, and New Zealand have introduced water fluoridation to varying degrees. Germany, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland have discontinued water fluoridation schemes for reasons which are not systematically available.[3]

Alternative methods

Water fluoridation is one of several methods of fluoride therapy; others include fluoridation of salt, milk, and toothpaste.[32]

The effectiveness of salt fluoridation is about the same as water fluoridation, if most salt for human consumption is fluoridated. Fluoridated salt reaches the consumer in salt at home, in meals at school and at large kitchens, and in bread. For example, Jamaica has just one salt producer, but a complex public water supply; it fluoridated all salt starting in 1987, resulting in a notable decline in the prevalence of cavities. Universal salt fluoridation is also practiced in Columbia, Jamaica, and the Canton of Vaud in Switzerland; in France and Germany fluoridated salt is widely used in households but unfluoridated salt is also available. Concentrations of fluoride in salt range from 90 mg/kg to 350 mg/kg, with studies suggesting an optimal concentration of around 250 mg/kg.[32]

Milk fluoridation is being practiced by the Borrow Foundation in some parts of Bulgaria, Chile, Peru, Russia, Thailand and the United Kingdom. For example, milk-powder fluoridation is used in Chilean rural areas where water fluoridation is not technically feasible.[33] These programs are aimed at children, and have neither targeted nor been evaluated for adults.[32] A 2005 systematic review found insufficient evidence to support the practice, but also concluded that studies suggest that fluoridated milk benefits schoolchildren, especially their permanent teeth.[34]

Some dental professionals are concerned that the growing use of bottled water may decrease the amount of fluoride exposure people will receive.[35] Some bottlers such as Danone have begun adding fluoride to their water.[36] On April 17, 2007, Medical News Today stated, "There is no correlation between the increased consumption of bottled water and an increase in cavities."[37] In October 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a health claim notification permitting water bottlers to claim that fluoridated bottled water can promote oral health. The claims are not allowed to be made on bottled water marketed to infants.[38]

History

Template:Cleanup-section

The history of water fluoridation can be divided into three periods. The first (c. 1901–33) was research into the cause of a form of mottled tooth enamel called "Colorado brown stain", which later became known as fluorosis. The second (c. 1933–45) focused on the relationship between fluoride concentrations, fluorosis, and tooth decay. The third period, from 1945 on, focused on adding fluoride to community water supplies.[2]

Colorado brown stain

While the use of fluorides for prevention of dental caries (cavities) was discussed in the 19th century in Europe,[39] community water fluoridation in the United States is partly due to the research of Dr. Frederick McKay, who pressed the dental community for an investigation into what was then known as "Colorado Brown Stain."[40] The condition, now known as dental fluorosis, when in its severe form is characterized by cracking and pitting of the teeth.[41][42][43] Of 2,945 children examined in 1909 by Dr. McKay, 87.5% had some degree of stain or mottling. All the affected children were from the Pikes Peak region. Despite the negative impact on the physical appearance of their teeth, the children with stained, mottled and pitted teeth also had fewer cavities than other children. McKay brought this to the attention of Dr. G.V. Black, and Black's interest was followed by greater interest within the dental profession.

Initial hypotheses for the staining included poor nutrition, overconsumption of pork or milk, radium exposure, childhood diseases, or a calcium deficiency in the local drinking water.[40] In 1931, researchers from the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) concluded that the cause of the Colorado stain was a high concentration of fluoride ions in the region's drinking water (ranging from 2 to 13.7 mg/L) and areas with lower concentrations had no staining (1 mg/L or less).[44] Pikes Peak's rock formations contained the mineral cryolite, one of whose constituents is fluorine. As the rain and snow fell, the resulting runoff water dissolved fluoride which made its way into the water supply.

Dental and aluminum researchers then moved toward determining a relatively safe level of fluoride chemicals to be added to water supplies. The research had two goals: (1) to warn communities with a high concentration of fluoride of the danger, initiating a reduction of the fluoride levels in order to reduce incidences of fluorosis, and (2) to encourage communities with a low concentration of fluoride in drinking water to add fluoride chemicals in order to help prevent tooth decay. By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occuring fluoride.[29]

Early studies

{{#invoke:Message box|ambox}} A study of varying amounts of fluoride in water was led by Dr. H. Trendley Dean, a dental officer of the U.S. Public Health Service.[45][46] In 1936 and 1937, Dr. Dean and other dentists compared statistics from Amarillo, which had 2.8 - 3.9 mg/L fluoride content, and low fluoride Wichita Falls. The data is alleged to show less cavities in Amarillo children, but the studies were never published.[47] Dr. Dean's research on the fluoride-dental caries relationship, published in 1942, included 7,000 children from 21 cities in Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The study concluded that the optimal amount of fluoride which minimized the risk of severe fluorosis but had positive benefits for tooth decay was 1 mg per day, per adult. Although fluoride is more abundant in the environment today, this was estimated to correlate with the concentration of 1 mg/L.

In 1937, dentists Henry Klein and Carroll E. Palmer had considered the possibility of fluoridation to prevent cavities after their evaluation of data gathered by a Public Health Service team at dental examinations of Native American children.[48] In a series of papers published afterwards (1937-1941), yet disregarded by his colleagues within the U.S.P.H.S., Klein summarized his findings on tooth development in children and related problems in epidemiological investigations on caries prevalence.[citation needed]

In 1939, Dr. Gerald J. Cox[49] conducted laboratory tests using rats that were fed aluminum and fluoride. Dr. Cox suggested adding fluoride to drinking water (or other media such as milk or bottled water) in order to improve oral health.[50]

In the mid 1940s, four widely cited studies were conducted. The researchers investigated cities that had both fluoridated and unfluoridated water. The first pair was Muskegon, Michigan and Grand Rapids, Michigan, making Grand Rapids the first community in the world to add fluoride chemicals to its drinking water to try to benefit dental health on January 25, 1945.[51] Kingston, New York was paired with Newburgh, New York.[52] Oak Park, Illinois was paired with Evanston, Illinois. Sarnia, Ontario was paired with Brantford, Ontario, Canada.[53]

In 1952 Nebraska Representative A.L. Miller complained that there had been no studies carried out to assess the potential adverse health risk to senior citizens, pregnant women or people with chronic diseases from exposure to the fluoridation chemicals.[47] A decrease in the incidence of tooth decay was found in some of the cities which had added fluoride chemicals to water supplies. The early comparison studies would later be criticized as, "primitive," with a, "virtual absence of quantitative, statistical methods...nonrandom method of selecting data and...high sensitivity of the results to the way in which the study populations were grouped..." in the journal Nature.[54]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001). Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 50 (RR-14): 1–42.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ripa LW (1993). A half-century of community water fluoridation in the United States: review and commentary. J Public Health Dent 53 (1): 17–44.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Cheng KK, Chalmers I, Sheldon TA (2007). Adding fluoride to water supplies. BMJ 335 (7622): 699–702.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 McDonagh MS, Whiting PF, Wilson PM et al. (2000). Systematic review of water fluoridation. BMJ 321 (7265): 855–9. The full report is at: McDonagh MS, Whiting PF, Bradley M et al. (2000). "A systematic review of water fluoridation". CRD Report 18. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Yeung CA (2008). A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation. Evid Based Dent 9 (2): 39–43. The full report is at: A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation (PDF). Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (2007). Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Armfield JM (2007). When public action undermines public health: a critical examination of antifluoridationist literature. Aust New Zealand Health Policy 4: 25.

- ↑ Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB (2007). Dental caries. Lancet 369 (9555): 51–9.

- ↑ Petersen PE, Lennon MA (2004). Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in the 21st century: the WHO approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 32 (5): 319–21.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Reeves TG (1986). Water fluoridation: a manual for engineers and technicians (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ↑ Nicholson JW, Czarnecka B (2008). "Fluoride in dentistry and dental restoratives", in Tressaud A, Haufe G (eds.): Fluorine and Health. Elsevier, 333–78. ISBN 978-0-444-53086-8.

- ↑ Division of Oral Health, National Center for Prevention Services, CDC (1993). "Fluoridation census 1992". Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Taricska JR, Wang LK, Hung YT, Li KH (2006). "Fluoridation and defluoridation", in Wang LK, Hung YT, Shammas NK (eds.): Advanced Physicochemical Treatment Processes, Handbook of Environmental Engineering 4. Humana Press, 293–315. DOI:10.1007/978-1-59745-029-4_9. ISBN 978-1-59745-029-4.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Bailey W, Barker L, Duchon K, Maas W (2008). Populations receiving optimally fluoridated public drinking water—United States, 1992–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57 (27): 737–41.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Pizzo G, Piscopo MR, Pizzo I, Giuliana G (2007). Community water fluoridation and caries prevention: a critical review. Clin Oral Investig 11 (3): 189–93.

- ↑ Aoba T, Fejerskov O (2002). Dental fluorosis: chemistry and biology. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 13 (2): 155–70.

- ↑ Yeung CA (2007). Fluoride prevents caries among adults of all ages. Evid Based Dent 8 (3): 72–3.

- ↑ Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V (2007). Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults. J Dent Res 86 (5): 410–5.

- ↑ Top 10 U.S. public health achievements in 20th century:

- CDC (1999). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 48 (12): 241–3. Reprinted in: (1999). {{{title}}}. JAMA 281 (16): 1481.

- Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 48 (41): 933–40. Reprinted in: (2000). {{{title}}}. JAMA 283 (10): 1283–6.

- ↑ Burt BA, Tomar SL (2007). "Changing the face of America: water fluoridation and oral health", in Ward JW, Warren C: Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America. Oxford University Press, 307–22. ISBN 0195150694.

- ↑ Gessner BD, Beller M, Middaugh JP, Whitford GM (1994). Acute fluoride poisoning from a public water system. N Engl J Med 330 (2): 95–9.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Pollick HF (2004). Water fluoridation and the environment: current perspective in the United States. Int J Occup Environ Health 10 (3): 343–50.

- ↑ Coplan M J, Patch SC, Masters R D, Bachman MS (2007), "Confirmation of and explanations for elevated blood lead and other disorders in children exposed to water disinfection and fluoridation chemicals", Neurotoxicology 28 (5): 1032–42, DOI:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.02.012

- ↑ ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations (2005). National and international organizations that recognize the public health benefits of community water fluoridation for preventing dental decay. American Dental Association. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ↑ Petersen PE (2008). World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health—World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J 58 (3): 115–21.

- ↑ Carmona RH (2004-07-28). Surgeon General's statement on community water fluoridation (PDF). U.S. Public Health Service. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ↑ ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations (2005). Fluoridation facts (PDF). American Dental Association. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ↑ Newbrun E (1996). The fluoridation war: a scientific dispute or a religious argument?. J Public Health Dent 56 (5 Spec No): 246–52.

- ↑ Klein RJ (2008-02-07). Healthy People 2010 Progress Review, Focus Area 21, Oral Health. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC (2008-09-17). Water fluoridation statistics for 2006. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ↑ The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health (2004). "The extent of water fluoridation", One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation, 2nd, 55–80. ISBN 095476840X.

- ↑ Ingram, Colin. (2006). The Drinking Water Book. pp. 15-16

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Jones S, Burt BA, Petersen PE, Lennon MA (2005). The effective use of fluorides in public health. Bull World Health Organ 83 (9): 670–6.

- ↑ Bánóczy J, Rugg-Gunn AJ (2006). Milk—a vehicle for fluorides: a review. Rev Clin Pesq Odontol 2 (5–6): 415–26.

- ↑ Yeung CA, Hitchings JL, Macfarlane TV, Threlfall AG, Tickle M, Glenny AM (2005). Fluoridated milk for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD003876.

- ↑ Smith, Michael. "Bottled Water Cited as Contributing to Cavity Comeback", from the MedPage Today website, page accessed 29 April, 2006.

- ↑ Press release from the Water Industry News website]

- ↑ Bottled Water And Fluoride Facts

- ↑ Why was the interim guidance on infant formula and fluoride issued? American Dental Association Website accessed May 28, 2008 [1]

- ↑ Meiers, Peter: "Early Fluoride research in Europe" from the Fluoride History website, page accessed 21 May, 2006.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 History of Dentistry in the Pikes Peak Region,Colorado Springs Dental Society webpage, page accessed 25 February, 2006.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ McGraw-Hill's AccessScience

- ↑ Report Judges Allowable Fluoride Levels in Water : NPR

- ↑ Meiers, Peter: "The Bauxite Story - A look at ALCOA", from the Fluoride History website, page accessed 12 May, 2006.

- ↑ Dean, H.T. "Classification of mottled enamel diagnosis." Journal of the American Dental Association, 21, 1421 - 1426, 1934.

- ↑ Dean, H.T. "Chronic endemic dental fluorosis." Journal of the American Dental Association, 16, 1269 - 1273, 1936.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Questionable Fluoride Safety Studies: Bartlett - Cameron, Newburgh - Kingston

- ↑ Klein H., Palmer C.E.: "Dental caries in American Indian children", Public Health Bulletin, No. 239, Dec. 1937

- ↑ Meiers, Peter: "Gerald Judy Cox".

- ↑ Cox, G.J., M.C. Matuschak, S.F. Dixon, M.L. Dodds, W.E. Walker. "Experimental dental caries IV. Fluorine and its relation to dental caries. Journal of Dental Research, 18, 481-490, 1939. Copy of original paper can be found here.

- ↑ After 60 Years of Success, Water Fluoridation Still Lacking in Many Communities. Medical News Today website, accessed 26 February, 2006.

- ↑ Ast, D.B., D.J. Smith, B. Wacks, K.T. Cantwell. "Newburgh-Kingston caries-fluorine study XIV. Combined clinical and roentgenographic dental findings after ten years of fluoride experience." Journal of the American Dental Association, 52, 314-25, 1956.

- ↑ Brown, H., M. Poplove. "The Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford Fluoridation Caries Study: Final Survey, 1963." Canadian Journal of Public Health,56, 319–24, 1965.

- ↑ Diesendorf, Mark The mystery of declining tooth decay Nature, July 10, 1986

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

- Fluoridation at the Open Directory Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.