Difference between revisions of "Sermon on the Mount" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Structure) |

m (→Structure) |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

'''Discourse on ostentation''' (Matthew 6) — Jesus criticizes [[fasting]], [[alms]], and [[prayer]] when they are only done for show, and not from the heart. Within the context of his criticism of hypocritical prayer, Jesus provides his famous example of correct prayer, known as [[The Lord's Prayer]]. The discourse goes on to urge the disciples not to worry about material needs, but to seek God's kingdom first and store their "treasures in heaven." | '''Discourse on ostentation''' (Matthew 6) — Jesus criticizes [[fasting]], [[alms]], and [[prayer]] when they are only done for show, and not from the heart. Within the context of his criticism of hypocritical prayer, Jesus provides his famous example of correct prayer, known as [[The Lord's Prayer]]. The discourse goes on to urge the disciples not to worry about material needs, but to seek God's kingdom first and store their "treasures in heaven." | ||

| − | '''Discourse on holiness'' (Matthew 7:1-29) — Jesus condemns those who judge others before first judging themselves, encouraging his disciples to "seek and knock," for they way, though narrow, shall be opened to them. He warns against [[false prophet]]s, for the "tree" is known by its "fruit." Finally, he concludes by urging his disciples to be not only "hearers" but "doers" of his teachings, for mere "hearers" build on a shifting foundations while "doers" built on solid rock. | + | '''Discourse on holiness''' (Matthew 7:1-29) — Jesus condemns those who judge others before first judging themselves, encouraging his disciples to "seek and knock," for they way, though narrow, shall be opened to them. He warns against [[false prophet]]s, for the "tree" is known by its "fruit." Finally, he concludes by urging his disciples to be not only "hearers" but "doers" of his teachings, for mere "hearers" build on a shifting foundations while "doers" built on solid rock. |

==Interpretation==<!-- This section is linked from [[Epistle to the Hebrews]] —> | ==Interpretation==<!-- This section is linked from [[Epistle to the Hebrews]] —> | ||

Revision as of 20:45, 4 December 2008

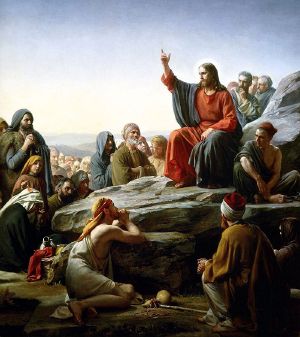

The Sermon on the Mount is speech reportedly given by Jesus of Nazareth in the Gospel of Matthew, epitomizing his moral teaching in the context of the Mosaic Law. As recorded in to chapters 5-7, Jesus gave this sermon (estimated around 30 C.E.) on a mountainside to his disciples.

While biblical literalists believe these verse represent an accurate record of an actual speech given by the historical Jesus, critical scholars take it to be a compilation of sayings attributed to Jesus, some historical some not.

Some Christians believe that the Sermon on the Mount represents a commentary on the Ten Commandments in which Christ appears as as the new Moses and true interpreter of the Mosaic Law. To many, the sermon contains the central tenets of Christian discipleship, and is considered as such by numerous religious and moral thinkers, such as Tolstoy, Gandhi, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Martin Luther King, Jr.. It has also been one of the main sources of Christian pacifism.

The best-known portions of the open-air sermon comprise the Beatitudes, found at the beginning of the section. The sermon also contains the Lord's Prayer and the injunctions to "resist not evil" and "turn the other cheek," as well as Jesus' version of the Golden Rule. Other lines often quoted are the references to "salt of the Earth," "light of the world," and "judge not, lest ye be judged." It concludes with an admonition not only to hear Jesus' words words, but to do them, a teaching which some commentators find to be at odds with the Pauline emphasis on believing in Jesus rather than "works" as the key to salvation.

Origin

The Gospel of Matthew groups Jesus' teachings into five discourses, of which the Sermon on the Mount is the first. Those accepting the ancient church tradition of Matthean authorship take the Sermon on the Mount as what it purports to be (Matthew 5:2), namely the actual words of Jesus given on the occasion described. Others, however, point out that it contains a number of parallels with Luke's Sermon on the Plain. Rather than being two versions of a similar speeches given in two different venues, modern scholars tend to see portions of the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain as having been drawn from a common "sayings source" document known as Q. Tending to confirm this idea is that fact that some of the sayings can also be found in the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas. However, others argue that the parallels in Luke tend to be very loose, and that the Gospel of Thomas could have borrowed the verses either from Matthew or Luke.

Matthew sets the Sermon on the Mount near the very beginning of Jesus' ministry. After being baptized by John the Baptist (chapter 3), Jesus is tempted by Satan in the wilderness (4:11). He then learns that John has been arrested and returns to Galilee. There, he begins to preach the same message that John did: "Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is hand." In Galilee, Jesus gathers disciples and begins to a attract a wider following as a healer and exorcist. News of his ministry spreads throughout the area, including not only of the Galilee but also Syria, the Decapolis, the Transjordan, and Judea (4:2-25).

In Matthew, the first teaching of Jesus, distinct from the message already proclaimed by his forerunner John, is the Sermon on the Mount. Seeing the crowds, he walks up a mountain side and sits down. However, it is not the crowds whom Jesus addresses, but his disciples: "His disciples came to him, and he began to teach them." (5:1-2) Indeed, some commentators indicate that Jesus seems have gone up the mountain not to gain a better platform from which to address a large audience, but to escape those who have been attracted by his healing ministry so that he may address his disciples in private.

There are no actual mountains in this part of Galilee, but there are several prominent hills in the region to the west of the Sea of Galilee, and so a number of scholars do not feel "the mountain" is the most accurate understanding of the phrase.

One possible location of the sermon is on a hill that rises near Capernaum. Known in ancient times as Mt. Eremos and Karn Hattin, this hill is now the site of a twentieth century Roman Catholic chapel called the Church of the Beatitudes.

The reference to going up a mountain prior to preaching is considered by many to be deliberate reference to Moses on Mount Sinai, and though Hill disagrees, arguing that the links would have been made far clearer, Lapide feels that the clumsy phrasing implies that this verse is an exact transliteration from the Hebrew passage describing Moses. Augustine of Hippo in his commentary on the Sermon on the Mount supported the Moses parallel, arguing that this symbolism showed Jesus is supplementing the precepts of Moses, although in his later writings, such as the Reply to Faustus, he backs away from this view.

Comparisons with the Sermon on the Plain

The Sermon on the Mount may be compared with the similar but more succinct Sermon on the Plain as recounted by the Gospel of Luke (6:17–49), which occurs at a similar moment in Luke's narrative, although Luke first provides additional details about Jesus' work in and around Nazareth. In Luke's version, Jesus ascends a mountain to pray with his disciples and then comes down and delivers his sermon to a large crowd in a level place. Some scholars believe that this is simply Luke's account of the same sermon, while others hold that Jesus simply gave similar sermons in different places, as do many preachers. Still others the "sermon" represents the authors' way of presenting a number of sayings of Jesus recorded in the Q document as if they were part of a single sermon.[1]

Structure

The sermon comprises the following components:

Introductory narrative (Matthew 5:1-2) — A large crowd assembles due to Jesus healing the sick, so he climbs a mountain and speaks to his disciples.

The Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3-12) — A series of eight (or nine) blessings describing the character of the people of the kingdom, such as meekness, purity of heart, humility, being and peacemaker, and experiencing persecution.

Metaphors of Salt and Light (Matthew 5:13-16) — This concludes the picture of God's people drawn in the beatitudes, who are called the "salt of the earth" and the "light of the world." In includes a stern warning to those who disciples who lose fail to manifest these characteristics.

Expounding of the Law (Matthew 5:17-48) — Jesus declares his commitment to the Mosaic Law "until heaven and earth shall pass away." His disciples must keep the commandments more carefully than the Pharisees do, and must go even beyond the requirements of certain of the commandments: not just "do not kill," but do not be angry; not just "do not commit adultery," but do not even look at a woman with lust; not just "love you neighbor," but "love you enemy," etc. The disciples must "be perfect as your Heavenly Father is perfect."

Discourse on ostentation (Matthew 6) — Jesus criticizes fasting, alms, and prayer when they are only done for show, and not from the heart. Within the context of his criticism of hypocritical prayer, Jesus provides his famous example of correct prayer, known as The Lord's Prayer. The discourse goes on to urge the disciples not to worry about material needs, but to seek God's kingdom first and store their "treasures in heaven."

Discourse on holiness (Matthew 7:1-29) — Jesus condemns those who judge others before first judging themselves, encouraging his disciples to "seek and knock," for they way, though narrow, shall be opened to them. He warns against false prophets, for the "tree" is known by its "fruit." Finally, he concludes by urging his disciples to be not only "hearers" but "doers" of his teachings, for mere "hearers" build on a shifting foundations while "doers" built on solid rock.

Interpretation

One of the most important debates over the sermon is how directly it should be applied to everyday life. Almost all Christian groups have developed nonliteral ways to interpret and apply the sermon. McArthur lists twelve basic schools of thought on these issues:

- The Absolutist View rejects all compromise and believes that, if obeying the scripture costs the welfare of the believer, then that is a reasonable sacrifice for salvation. All the precepts in the Sermon must be taken literally and applied universally. Proponents of this view include St. Francis of Assisi, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and in later life Leo Tolstoy. The Oriental Orthodox Churches fully adopt this position; among heterodox groups, the early Anabaptists came close, and modern Anabaptist groups such as the Mennonites and Hutterites come closest.

- One method that is common, but not endorsed by any denomination, is to simply Modify the Text of the sermon. In ancient times this took the form of actually altering the text of the Sermon to make it more palatable. Thus some early copyists changed Matthew 5:22 from "whosoever is angry with his brother shall be in danger of the judgment" to the watered-down "whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment." "Love your enemies" was changed to "Pray for your enemies" in pOxy 1224 6:1a; Did. 1:3; Pol. Phil. 12:3. John 13:34-35 tells the disciples to "Love one another". The exception for divorce in the case of porneia may be a Matthean addition; it is not present in Luke 16:18, Mark 10:11, or 1 Cor 7:10–11; and in 1 Cor 7:12–16, Paul gives his own exceptions to Jesus' teaching. Additions were made to the Lord's Prayer to support other doctrines, and other prayers were developed as substitute. More common in recent centuries is to paraphrase the Sermon and in so doing make it far less radical. A search through the writings of almost every major Christian writer finds them at some point to have made this modification. [citation needed][2]

- One of the most common views is the Hyperbole View, which argues that portions of what Jesus states in the Sermon are hyperbole, and that if one is to apply the teaching to the real world, they need to be "toned down." Most interpreters agree that there is some hyperbole in the sermon, with Matt 5:29 being the most prominent example, but there is disagreement over exactly which sections should not be taken literally.

- Closely related is the General Principles View that argues that Jesus was not giving specific instructions, but general principles of how one should behave. The specific instances cited in the Sermon are simply examples of these general principles.

- The Double Standard View is the official position of the Roman Catholic Church. It divides the teachings of the Sermon into general precepts and specific counsels. Obedience to the general precepts is essential for salvation, but obedience to the counsels is only necessary for perfection. The great mass of the population need only concern themselves with the precepts; the counsels must be followed by only a pious few such as the clergy and monks. This theory was initiated by St. Augustine and later fully developed by St. Thomas Aquinas, though an early version of it is cited in Did. 6:2, "For if you are able to bear the entire yoke of the Lord, you will be perfect; but if you are not able to do this, do what you are able" (Roberts-Donaldson), and reflected in the Apostolic Decree of the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15:19-21). Geoffrey Chaucer also did much to popularize this view among speakers of English with his Canterbury Tales (Wife of Bath's Prologue, v. 117-118)

- Martin Luther rejected the Roman Catholic approach and developed a different two-level system McArthur refers to as the Two Realms View. Luther divided the world into the religious and secular realms and argued that the Sermon only applied to the spiritual. In the temporal world, obligations to family, employers, and country force believers to compromise. Thus a judge should follow his secular obligations to sentence a criminal, but inwardly, he should mourn for the fate of the criminal.

- At the same time as the Protestant Reformation was underway, a new era of Biblical criticism began leading to the Analogy of Scripture View. Close reading of the Bible found that several of the most rigid precepts in the sermon were moderated by other parts of the New Testament. For instance, while Jesus seems to forbid all oaths, Paul is shown using them at least twice; thus the prohibition in the Sermon may seem to have some exceptions; though in fairness to Paul, it should be pointed out that he was not present at the Sermon on the Mount and may not have been aware of all of its teachings. See also Pauline Christianity.

- In the nineteenth century, several more interpretations developed. Wilhelm Herrmann embraced the notion of Attitudes not Acts, which can be traced back to St. Augustine. This view states that Jesus in the Sermon is not saying how a good Christian should behave, only what his attitude is. The spirit lying behind the act is more important than the act itself.

- Albert Schweitzer popularized the Interim Ethic View. This view sees Jesus as being convinced that the world was going to end in the very near future. As such, survival in the world did not matter as in the end times material well-being would be irrelevant.

- In the twentieth century another major German thinker, Martin Dibelius, presented another view also based on eschatology. His Unconditional Divine Will View is that the ethics behind the Sermon are absolute and unbending, but the current fallen state of the world makes it impossible to live up to them. Humans are bound to attempt to live up to them, but failure is inevitable. This will change when the Kingdom of Heaven is proclaimed and all will be able to live in a Godly manner. A similar view is also described in Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, written in the late nineteenth century.

- Closely linked to this is the Repentance View, which is that Jesus intended for the precepts in his Sermon to be unattainable, and through our certain failure to live up to them, we will learn to repent or that we will be driven to faith in the Gospel.

- Another Eschatological View is that of modern dispensationalism. Dispensationalism, first developed by the Plymouth Brethren, divides human history into a series of ages or dispensations. Today we live in the period of grace where living up to the teachings of the sermon is impossible, but in the future, the Millennium will see a period where it is possible to live up to the teachings of the Sermon, and where following them will be a prerequisite to salvation.

E. Earle Ellis (Professor of Theology at SWBTS) says that this sermon is an Eschatological Invitation in which Jesus is inviting believers to live according to an ethic that will be standard in the future kingdom of God[citation needed]. As Ellis says, we are to speak Jesus' words, think his thoughts, and do his deeds. Since this will be the ethic of the future kingdom of God, believers should go ahead and adjust their lives to this ethic in this age.

See also

- Sermon on the Plain found in the Gospel of Luke

- Beatitudes

- The Kingdom of God is Within You

- Great Commission

- The Farewell Sermon

- Didache

- Hyperdispensationalism

- New Covenant

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Betz, Hans Dieter. Essays on the Sermon on the Mount. translations by Laurence Welborn. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985.

- Ehrman, Bart D. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, Oxford, 2004. ISBN 0-19-515462-2

- Fox, Emmet. The Sermon on the Mount: The Key to Success in Life and the Lord's Prayer : An Interpretation, 1989. ISBN 0-06-062862-6

- Kissinger, Warren S. The Sermon on the Mount: A History of Interpretation and Bibliography. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1975.

- Kodjak, Andrej. A Structural Analysis of the Sermon on the Mount. New York: M. de Gruyter, 1986.

- Lapide, Pinchas. The Sermon on the Mount, Utopia or Program for Action? translated from the German by Arlene Swidler. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1986.

- McArthur, Harvey King. Understanding the Sermon on the Mount. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1978.

- Prabhavananda, Swami Sermon on the Mount According to Vedanta 1991 ISBN 0-87481-050-7

- Knight, Christopher The Hiram Key Century Books, Random House, 1996

External links

- Text of the sermon (NAB)

- Text of the sermon (KJV)

- Text of the sermon (NIV)

- Augustine: On the Sermon on the Mount

- Catholic Catechism on The Moral Law

- Thoughts From the Mount of Blessing

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.