Samaritan Pentateuch

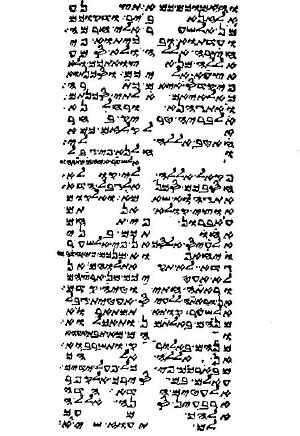

The Samaritan Pentateuch is the text of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible, also called the Torah or Law) that is used by the Samaritans. It is written in the Samaritan alphabet, which is believed by scholars to be an older form of Hebrew.

Scholars use the Samaritan Pentateuch to compare against other versions of the Pentateuch to determine the text of the original Pentateuch and to trace the development of text-families. Scrolls among the Dead Sea scrolls have been identified as proto-Samaritan Pentateuch text-type.[1]

The Samaritan practices are based on the five books of Moses, namely the Torah. They have a slightly different version of the Torah (Samaritan Pentateuch) than that accepted by the Jews and Christians. There are minor differences such as the ages of different people mentioned in bibliography, and major differences such as a commandment to be monogomous in the Samaritan Torah as opposed to their Jewish counterpart (Lev. 18:18).

Background

Samaritans descend from the northern Israelite kingdom of Israel. According to the Hebrew Bible, the political division between the southern kingdom of Judea and northern kingdom of Israel, took place after the reign of Solomon with the northern leader Jeroboam becoming the king of Israel and Rehoboam, the son of Solomon ruling Judah. The Samaritans, however, maintain that in fact the northern kingdom, the capital of which was Samaria, never joined the kingdom of David and Solomon. They contend that the Mount Gerizim, located near the ancient town of Shechem, is the location ordained by God as the authorized site of the Temple of Yahweh as described in the Torah. The Temple of Jerusalem was therefore never the true temple. Moreover, they rejected the Jewish priesthood as illegitimate, having descended from the priest Eli of Shiloh, who, according to Samaritan tradition, was originally a priest at Gerizim who established an unauthorized priestly tradition that was later moved to Jerusalem. They also reject both the northern and the southern kings, believing that God did not approve of either royal tradition.

In Jewish tradition, the northern kingdom was conquered by the Assyrians, and the southern kingdom by the Babylonians. Today's Samaritans are the remnants of those who were not exiled from the land during the Assyrian period, and who continuously practiced the ancient religion of Moses and passed it down even in the most difficult oppressed times. However, when the Jews returned from Babylonian exile, they rejected the Samaritans because they had intermarried with non-Israelites. The nation of Samaria thereafter became Judea's rival with its own Temple of Yahweh on Mount Gerizim. There were several wars between the Jews and Samaritans in history, on the basis of both religion and politics.

Samaritans accept on the Torah—the first five book of the Hebrew Bible, also called the Pentateuch—as authoritative, rejected the writings of the prophets and the wisdom literature which are part of the Jewish and Christian scriptures. They also reject the oral law of the Jews, namely the rabbinical traditions which came to be written in the Talmud. They use their own oral law, which has been practiced over the generations; and which they believe is the original practice that Moses taught the children of Israel at Mount Sinai assembly.

The most celebrated of the copies of the Samaritan Pentateuch is Abisha Scroll, which is used in the Samaritan synagogue of Nablus. This scroll was allegedly penned by the high priest Abisha, great-grandson of Aaron, thirteen years after the Israelites entry into the land of Israel under the leadership of Joshua, son of Nun. Abisha claims for himself the authorship of the manuscript in a speech in the first person at Deuteronomy 5:6 in the standard text. Modern scholars doubt that this could actually be the case, but the scroll is definitely of great antiquity.

Differences with the Hebrew text

The Samaritan Pentateuch is written in the Samaritan alphabet, which differs from the biblical Hebrew alphabet. It is considered by some to be the form in general use before the Babylonian captivity. There are also other peculiarities in the writing.

It is claimed that there are significant differences between the Hebrew and the Samaritan versions in the readings of many sentences. In about two thousand out of the six thousand instances in which the Samaritan and the Jewish texts (Masoretic text) differ, the Septuagint (LXX) agrees with the Samaritan. For example, Exodus 12:40 in the Samaritan and the LXX reads:

- "Now the sojourning of the children of Israel and of their fathers which they had dwelt in the land of Canaan and in Egypt was four hundred and thirty years."

In the Masoretic text, the passage reads:

- "Now the sojourning of the children of Israel, who dwelt in Egypt, was four hundred and thirty years." (Exodus 12:40)

The Samaritan version of the Ten Commandments commands them to build the altar on Mount Gerizim, which would be the site at which all sacrifices should be offered. [2]

Wider interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch commenced in 1616, when the well-known traveler Pietro della Valle brought from Damascus a copy of the text. Since then many copies have come to Europe and America. In 1645, an edited copy of the text was published in the Le Jay's (Paris) Polyglot by Jean Morin, a Jesuit-convert from Calvinism to Catholicism, who believed (without actual scholarly support) that the Septuagint and the Samaritan texts were superior to the Hebrew Masoretic text. It was republished again in Walton's Polyglot in 1657.

Scholarly evaluation of the Samaritan Pentateuch has changed after the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, some manuscripts of which display a text that corresponds closely to that of the Samaritan Pentateuch. This shows that, apart from the clearly Samaritan references to the worship of God on Mount Gerizim, the distinction at that date between the Samaritan and non-Samaritan versions was not as clear-cut as previously thought.

The first English translation of the Samaritan text is expected to be published by late 2008 by Benyamim Tsedaka, an active member of the Samaritan community.

=

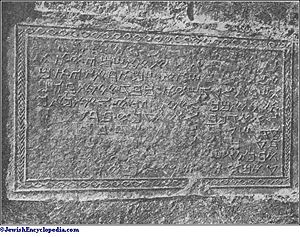

The most important of the works belonging to Samaritan literature is the Samaritan Pentateuch, that is the Pentateuch written in the Samaritan character in Hebrew, which is not to be confounded with the Samaritan Targum (see below). In the early Christian centuries this Pentateuch was frequently mentioned in the writings of the Fathers and in marginal notes to old manuscripts, but in the course of time it was forgotten. In 1616 Pietro della Valle obtained a copy by purchase at Damascus; this copy came into the possession of the library of the Oratory at Paris and was printed in 1645 in the Paris Polyglot. At the present time the manuscript, which is imperfect and dates from 1514, is in the Vatican Library. From the time of this publication the number of codices, some much older, has been greatly increased, and Kennicott was able to compare in whole or part sixteen manuscripts ["Vet. Test. Hebr." (Oxford, 1776)]. The views of scholars vary as to the antiquity of this Samaritan recension. Some maintain the opinion that the Samaritans became acquainted with the Pentateuch through the Jews who were left in the country, or through the priest mentioned in 2 Kings 17:28. Others, however, hold the view that the Samaritans did not come into possession of the Pentateuch until they were definitely formed into an independent community. This much, however, is certain: that it must have been already adopted by the time of the founding of the temple on Garizim, consequently in the time of Nehemias. It is, therefore, a recension which was in existence before the Septuagint, which fact makes evident its importance for the verification of the text of the Hebrew Bible.

A comparison of the Samaritan Pentateuch with the Masoretic text shows that the former varies from the latter in very many places and, on the other hand, very often agrees with the Septuagint. For the variant readings of the Samaritan Pentateuch see Kennicott, loc. cit., and for the most complete list see Petermann, loc. cit., 219-26. A systematic grouping of these variants is given by Gesenius, "De Pentateuchi Samaritani origine indole et auctoritate" (Halle, 1815), p. 46. Very many of these variations refer to orthographic and grammatic details which are of no importance for the sense of the text; others rest on evident blunders, while still others are plainly deliberate changes, as the removal of anthropomorphisms and expressions which seemed objectionable, the bringing into conformity of parallel passages, insertion of additions, large and small, different members in thegenealogies, corruptions in favour of the religious opinions of the Samaritans, among them, in Deuteronomy 27:4, the substitution of Garizim for Ebal’, and other like changes. Although, in comparison with the Masoretic text, the Samaritan Pentateuch shows many errors, yet it also contains readings which can be neither oversights nor deliberate changes, and of these a considerable number coincide with the Septuagint in opposition to the Masoretic text. Some scholars have sought to draw from this the conclusion that a copy of the Old Testament used by Samaritans settled in Egypt served as a model for the Septuagint. According to Kohn, "De Pentat. Samar." (Breslau, 1865), the translators of the Septuagint used a Græco-Samaritan version, while the same scholar later claims to trace back the agreements to subsequent interpolations from theSamareiticon [Kohn , "Samareiticon und Septuaginta" in "Magazin für Gesch. und Wissenschaft des Judentums" (1894), 1 sqq., 49 sqq.]. The simplest way of explaining the uniformity is the hypothesis that both the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Septuagint go back to a form of text common to the Palestinian Jews which varies somewhat from the Masoretic text which was settled later. However, taking everything together, the decision must be reached that the Masoretic tradition has more faithfully preserved the original form of the text.

The most celebrated of the manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch is that in the synagogue at Nablus. It is a roll made of the skins of rams, and written, according to the belief of the Samaritans, in the thirteenth year after the conquest of Canaan at the entrance to the Tabernacle on Mount Garizim by Abisha, a great-grandson of Aaron. Abisha claims for himself the authorship of the manuscript in a speech in the first person which is inserted between the columns of Deuteronomy 5:6 sqq., in the form of what is called a tarikh. This is of course a fable. The age of the roll cannot be exactly settled, as up to now it has not been possible to examine it thoroughly.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Canon Debate, McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 6: Questions of Canon through the Dead Sea Scrolls by James C. VanderKam, page 94, citing private communication with Emanuel Tov on biblical manuscripts: Qumran scribe type c.25%, proto-Masoretic Text c. 40%, pre-Samaritan texts c.5%, texts close to the Hebrew model for the Septuagint c.5% and nonaligned c.25%.

- ↑ Overview of the Differences Between the Jewish and Samaritan Versions of the Pentateuch

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

- Facsimile of the entire Samaritan Pentateuch (in Hebrew)

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Samaritans: Samaritan Version of the Pentateuch

This entry incorporates text from the public domain Easton's Bible Dictionary, originally published in 1897.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.