Difference between revisions of "Paradigm" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Paradigm,''' ([[Greek]]:παράδειγμα (paradigma), composite from para- and the verb δείχνυμι "to show," as a whole -roughly- meaning "example") ({{IPAEng|ˈpærədaɪm}}) designates a cluster of concepts such as [[assumption]]s, [[value]]s, practices, and [[methodology|methodologies]] shared by a community of researchers in a given discipline. The original Greek term "paradeigma" was used in Greek texts such as [[Plato]]'s Timaeus (28A) as the model or the pattern [[Demiurge]] (god) used to create the [[cosmos]]. The modern usage of the term, however, began when [[Thomas Kuhn]] used it in his ''Structure of Scientific | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}} |

| + | '''Paradigm,''' ([[Greek]]:παράδειγμα (paradigma), composite from para- and the verb δείχνυμι "to show," as a whole -roughly- meaning "example") ({{IPAEng|ˈpærədaɪm}}) designates a cluster of concepts such as [[assumption]]s, [[value]]s, practices, and [[methodology|methodologies]] shared by a community of researchers in a given discipline. The original Greek term "paradeigma" was used in Greek texts such as [[Plato]]'s Timaeus (28A) as the model or the pattern [[Demiurge]] (god) used to create the [[cosmos]]. The modern usage of the term, however, began when [[Thomas Kuhn]] used it in his ''Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' (1962). | ||

| − | Kuhn initially used the term "paradigm" in the contexts of history and [[philosophy of science]]. The term, however, was widely used in [[social sciences]] and [[human sciences]] and became a popular term in almost all disciplines. Upon receiving a number of | + | Kuhn initially used the term "paradigm" in the contexts of history and [[philosophy of science]]. The term, however, was widely used in [[social sciences]] and [[human sciences]] and became a popular term in almost all disciplines. Upon receiving a number of criticisms for the ambiguity of the concept, Kuhn proposed to rephrase it as "disciplinary matrix." |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | In pre-Kuhnian philosophy of science, [[natural science]] was believed to be a-historical, a-social, and interpretation-free discipline. Kuhn, however, pointed out that scientific theories were constructed within a certain paradigm shared by a scientific community, and that the paradigm is shaped by social, historical, and other extra-scientific factors. Kuhn's argument for the social, historical dimension of theories of natural science made a turn in the history of philosophy of science. [[Imre Lakatos]], [[Paul Feyerabend]], and others further pointed out the [[Confirmation holism|theory-ladenness]] or theory dependency of scientific data and [[hermeneutics|hermeneutic]] dimension of natural sciences. When Kuhn presented the concept of paradigm, he qualified its application to natural science alone in sharp distinction from its use in the social and human sciences. After 1970s, however, Kuhn extended his studies to hermeneutics and found an affinity between his view on natural science and the hermeneutics perspective on social and human sciences. In his later essay ''The Natural and the Human Sciences'', Kuhn rephrased the term paradigm as "hermeneutic core." Paradigm became thus one of the most influential concepts in the history of human thoughts in the twentieth century. | ||

| − | + | ==[[Plato]]'s ''Timaeus''== | |

| − | |||

| − | ==[[Plato]]'s | ||

The term "paradigm" is originally a Greek term. Plato, in his ''Timaeus'' (28A) for example, used it as a pattern or model which [[Demiurge]] (a craftsman god) used to make the cosmos: | The term "paradigm" is originally a Greek term. Plato, in his ''Timaeus'' (28A) for example, used it as a pattern or model which [[Demiurge]] (a craftsman god) used to make the cosmos: | ||

| − | <blockquote>The work of the creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect, but when he looks to the created only and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect.<ref>Plato, ''The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters,'' | + | <blockquote>The work of the creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect, but when he looks to the created only and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect.<ref>Plato, ''The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters,'' Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (eds.) (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961), 1161.</ref></blockquote> |

| − | In Plato's view, the pattern or the model of creation exist as [[Ideas]] in the eternal world which is [[transcendence|transcending]] a sensible, physical world people live in. The pre- | + | In Plato's view, the pattern or the model of creation exist as [[Ideas]] in the eternal world which is [[transcendence|transcending]] a sensible, physical world people live in. The pre-existing Ideas serve as the model "paradigm." Plato, however, did not develop this concept in any of his philosophical works beyond this usage. It was [[Thomas Kuhn]] who explored the concept and made it a contemporary term. |

==Kuhn's formulation of paradigm in the ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions''== | ==Kuhn's formulation of paradigm in the ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions''== | ||

===Scientific paradigm=== | ===Scientific paradigm=== | ||

{{main|Paradigm shift|Sociology of knowledge|Systemics|Commensurability (philosophy of science)|Confirmation holism}} | {{main|Paradigm shift|Sociology of knowledge|Systemics|Commensurability (philosophy of science)|Confirmation holism}} | ||

| − | + | The historian and [[philosophy of science|philosopher of science]] [[Thomas Kuhn]] gave this word its contemporary meaning when he adopted it to refer to the set of practices that define a scientific discipline. In his monumental work ''[[The Structure of Scientific Revolutions]]'' Kuhn defines a scientific paradigm as: | |

*''what'' is to be observed and scrutinized | *''what'' is to be observed and scrutinized | ||

| Line 23: | Line 24: | ||

*''how'' is an experiment to be conducted, and ''what'' equipment is available to conduct the experiment. | *''how'' is an experiment to be conducted, and ''what'' equipment is available to conduct the experiment. | ||

| − | Thus, within [[normal science]], | + | Thus, within [[normal science]], paradigm is the set of exemplary experiments that are likely to be copied or emulated. The prevailing paradigm often represents a more specific way of viewing reality, or limitations on acceptable ''programs'' for future research, than the much more general [[scientific method]]. |

| − | An example of a currently accepted paradigm would be the [[standard model]] of physics. The scientific method would allow for orthodox scientific investigations of many phenomena which might contradict or disprove the standard model. The presence of the standard model has [[sociology|sociological]] implications. | + | An example of a currently accepted paradigm would be the [[standard model]] of physics. The scientific method would allow for orthodox scientific investigations of many phenomena which might contradict or disprove the standard model. The presence of the standard model has [[sociology|sociological]] implications. For example, grant funding would be more difficult to obtain for such experiments, in proportion to the amount of departure from accepted standard model theory which the experiment would test for. An experiment to test for the [[mass]] of the [[neutrino]] or decay of the [[proton]] (small departures from the model), for example, would be more likely to receive money than experiments to look for the violation of the [[conservation of momentum]], or ways to engineer reverse time travel. |

One important aspect of Kuhn's paradigms is that the paradigms are [[Commensurability_%28philosophy_of_science%29 | incommensurable]], which means that two paradigms do not have a common standard by which one can directly compare, measure or assess competing paradigms. A new paradigm which replaces an old paradigm is not necessarily better, because the criteria of judgment depend on the paradigm. | One important aspect of Kuhn's paradigms is that the paradigms are [[Commensurability_%28philosophy_of_science%29 | incommensurable]], which means that two paradigms do not have a common standard by which one can directly compare, measure or assess competing paradigms. A new paradigm which replaces an old paradigm is not necessarily better, because the criteria of judgment depend on the paradigm. | ||

| − | ==Paradigm shifts== | + | ===Paradigm shifts=== |

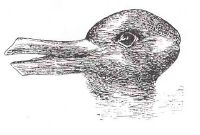

| − | + | [[Image:Duck-Rabbit illusion.jpg|right|200px|thumb|Kuhn used the duck-rabbit [[optical illusion]] to demonstrate the way in which a paradigm shift could cause one to see the same information in an entirely different way.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | A scientific revolution occurs, according to Kuhn, when scientists encounter anomalies which cannot be explained by the universally accepted paradigm within which scientific progress has thereto been made. The paradigm, in Kuhn's view, is not simply the current theory, but the entire [[worldview]] in which it exists and all of the implications which come with it. There are anomalies for all paradigms, Kuhn maintained, that are brushed away as acceptable levels of error, or simply ignored and not dealt with (a principal argument Kuhn uses to reject [[Karl Popper]]'s model of [[falsifiability]] as the key force involved in scientific change). Rather, according to Kuhn, anomalies have various levels of significance to the practitioners of science at the time. To put it in the context of early twentieth century physics, some scientists found the problems with calculating [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury's]] [[perihelion]] more troubling than the [[Michelson-Morley experiment]] results, and some the other way around. Kuhn's model of scientific change differs here, and in many places, from that of the [[logical positivists]] in that it puts an enhanced emphasis on the individual humans involved as scientists, rather than abstracting science into a purely logical or philosophical venture. | |

| − | + | When enough significant anomalies have accrued against a current paradigm, the scientific discipline is thrown into a state of ''crisis,'' according to Kuhn. During this crisis, new ideas, perhaps ones previously discarded, are tried. Eventually a ''new'' paradigm is formed, which gains its own new followers, and an intellectual "battle" takes place between the followers of the new paradigm and the hold-outs of the old paradigm. Again, for early twentieth-century [[physics]], the transition between the [[James Clerk Maxwell|Maxwellian]] [[Maxwell's equations|electromagnetic worldview]] and the [[Albert Einstein|Einsteinian]] [[theory of relativity|Relativistic]] worldview was not instantaneous nor calm, and instead involved a protracted set of "attacks," both with empirical data as well as rhetorical or philosophical arguments, by both sides, with the Einsteinian theory winning out in the long-run. Again, the weighing of evidence and importance of new data was fit through the human sieve: some scientists found the simplicity of Einstein's equations to be most compelling, while some found them more complicated than the notion of Maxwell's aether which they banished. Some found [[Arthur Eddington|Eddington's]] photographs of [[light]] bending around the [[sun]] to be compelling, some questioned their accuracy and meaning. Sometimes the convincing force is just time itself and the human toll it takes, Kuhn said, using a quote from [[Max Planck]]: "a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it." | |

| − | + | After a given discipline has changed from one paradigm to another, this is called, in Kuhn's terminology, a ''scientific revolution'' or a ''paradigm shift''. It is often this final conclusion, the result of the long process, that is meant when the term ''paradigm shift'' is used colloquially: simply the (often radical) change of worldview, without reference to the specificities of Kuhn's historical argument. | |

| − | + | == Paradigm in social and human sciences == | |

| − | + | When Kuhn presented the concept of paradigm in ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,'' he did not consider the concept as appropriate for the social sciences. He explains in his preface to ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' that he presented the concept of paradigm precisely in order to distinguish the social from the natural sciences (p.''x'').<ref>The distinction between natural sciences and human, social sciences had been discussed in the tradition of [[hermeneutics]]. [[Dilthey]] distinguished human sciences, which require interpretive understanding, whereas natural science requires non-hermeneutic, causal explanation. (see [[Dilthey]])</ref> He wrote this book at the [[Palo Alto]] Center for Scholars, surrounded by social scientists, when he observed that they were never in agreement on theories or concepts. He explains that he wrote this book precisely to show that there are no, nor can be, any paradigms in the social sciences. Mattei Dogan, a French sociologist, in his article "Paradigms in the Social Sciences," develops Kuhn's original thesis that there are no paradigms at all in the social sciences since the concepts are polysemic, the deliberate mutual ignorance and disagreement between scholars and the proliferation of schools in these disciplines. Dogan provides many examples of the inexistence of paradigms in the social sciences in his essay,<ref>Mattei Dogan, "Paradigms in the Social Sciences," in ''International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences'', Volume 16, 2001.</ref> particularly in [[sociology]], [[political science]] and [[political anthropology]]. | |

| − | + | The concept of paradigm, however, influenced not only [[philosophy of science|philosophers of natural science]], but also scholars in [[social sciences]] and [[human sciences]]. In these disciplines, fundamental presuppositions or a framework of thought often determine the [[hermeneutics|hermeneutic]] horizon of scientists. The concept of paradigm appeared appropriate to describe those fundamental frameworks of thinking, if its meaning is broadly construed. In the social and human sciences, paradigms may be shared by a much narrower community of scientists who belong to the same school or share the similar perspectives. The concept of paradigm received wider acceptance and became one of the most popular terms in the late twentieth century. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The interpretive dimension of social and human sciences had been long discussed in the tradition of [[hermeneutics]]. [[Wilhelm Dilthey]] (1833-1911) distinguished "human sciences" or "spiritual sciences" (German: Geisteswissenschaften) from natural sciences precisely because the former is a hermeneutic discipline which requires interpretive "understanding" (German: Verstehen) while the latter give interpretation-free causal "explanation." | |

| − | + | Kuhn's thesis that natural sciences are built upon certain socially, historically conditioned paradigms changed the standard view of natural sciences among hermeneutics as well as philosophers of natural science. Kuhn's view of natural science suggests the existence of a hermeneutic dimension of natural sciences and triggered discussion regarding the distinction of these two types of sciences. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | After the seventies, Kuhn himself extended his research to [[hermeneutics]]. He realized a close affinity between natural sciences and social, human sciences. In the essay "The Natural and the Human Sciences," presented at a panel discussion with [[Charles Taylor]] in 1989,<ref>Kuhn presented "The Natural and the Human Sciences" at the panel discussion at LaSalle University, February 11, 1989. It was published in ''The Interpretative Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture'' (1991). The essay is also included in ''The Road Since Structure'' (2000).</ref> Kuhn pointed out the hermeneutic dimension of natural sciences and the resemblance between natural sciences and social, human sciences. He rephrased paradigm as "hermeneutic core" in the essay. Unfortunately, Kuhn did not develop the issue further. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 116: | Line 62: | ||

==References and Links== | ==References and Links== | ||

| − | *Clarke, Thomas and Clegg | + | * Clarke, Thomas and Stewart Clegg (eds.). ''Changing Paradigms.'' London: HarperCollins, 2000.ISBN 0-00-638731-4 |

| − | * | + | * Dogan, Mattei. "Paradigms in the Social Sciences," in ''International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences,'' Volume 16, edited by Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes. New York: Elsevier Science, 2001. |

| − | + | * Kuhn, Thomas S. “The Natural and the Human Sciences,” in ''The Interpretative Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture,'' edited by D. Hiley, J. Bohman, and R. Shusterman, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991. (The same essay is also included in Kuhn, Thomas S., James Conant, and John Haugeland. ''The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970-1993, with an Autobiographical Interview.'' Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 2002. ISBN 9780226457994 | |

| − | * Kuhn, Thomas S. “The Natural and the Human Sciences,” in ''The Interpretative Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture,'' edited by D. Hiley, J. Bohman, and R. Shusterman, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991. The same essay is | + | * ———. ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'', 3rd ed. Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3 |

| − | * Masterman, Margaret | + | * Masterman, Margaret. "The Nature of a Paradigm," pp. 59-89 in Imre Lakatos and Alan Musgrave, ''Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge''. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1970. ISBN 0-521-09623-5 |

| − | * | + | * Plato. ''The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters,'' edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. New York: Pantheon Books, 1961. |

| − | * | + | * Von Dietze, Erich. ''Paradigms Explained: Rethinking Thomas Kuhn's Philosophy of Science.'' Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2001. ISBN 9780275969998 |

| − | * [http:// | + | |

| − | * | + | ==External links== |

| − | * | + | All links retrieved November 18, 2022. |

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/thomas-kuhn/ Thomas Kuhn], Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. | ||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rationality-historicist/ Historicist Theories of Rationality], Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. | ||

| + | * Kuhn, Thomas. [http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/us/kuhn.htm IX. The Nature and Necessity of Scientific Revolutions], ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. | ||

| + | '' | ||

| + | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | ||

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg]. | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:philosophy]] |

| + | [[category:politics and social sciences]] | ||

| − | {{credits|Paradigm|223803435}} | + | {{credits|Paradigm|223803435|Paradigm_shift|231793546}} |

Latest revision as of 07:43, 18 November 2022

Paradigm, (Greek:παράδειγμα (paradigma), composite from para- and the verb δείχνυμι "to show," as a whole -roughly- meaning "example") (IPA: /ˈpærədaɪm/) designates a cluster of concepts such as assumptions, values, practices, and methodologies shared by a community of researchers in a given discipline. The original Greek term "paradeigma" was used in Greek texts such as Plato's Timaeus (28A) as the model or the pattern Demiurge (god) used to create the cosmos. The modern usage of the term, however, began when Thomas Kuhn used it in his Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962).

Kuhn initially used the term "paradigm" in the contexts of history and philosophy of science. The term, however, was widely used in social sciences and human sciences and became a popular term in almost all disciplines. Upon receiving a number of criticisms for the ambiguity of the concept, Kuhn proposed to rephrase it as "disciplinary matrix."

In pre-Kuhnian philosophy of science, natural science was believed to be a-historical, a-social, and interpretation-free discipline. Kuhn, however, pointed out that scientific theories were constructed within a certain paradigm shared by a scientific community, and that the paradigm is shaped by social, historical, and other extra-scientific factors. Kuhn's argument for the social, historical dimension of theories of natural science made a turn in the history of philosophy of science. Imre Lakatos, Paul Feyerabend, and others further pointed out the theory-ladenness or theory dependency of scientific data and hermeneutic dimension of natural sciences. When Kuhn presented the concept of paradigm, he qualified its application to natural science alone in sharp distinction from its use in the social and human sciences. After 1970s, however, Kuhn extended his studies to hermeneutics and found an affinity between his view on natural science and the hermeneutics perspective on social and human sciences. In his later essay The Natural and the Human Sciences, Kuhn rephrased the term paradigm as "hermeneutic core." Paradigm became thus one of the most influential concepts in the history of human thoughts in the twentieth century.

Plato's Timaeus

The term "paradigm" is originally a Greek term. Plato, in his Timaeus (28A) for example, used it as a pattern or model which Demiurge (a craftsman god) used to make the cosmos:

The work of the creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect, but when he looks to the created only and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect.[1]

In Plato's view, the pattern or the model of creation exist as Ideas in the eternal world which is transcending a sensible, physical world people live in. The pre-existing Ideas serve as the model "paradigm." Plato, however, did not develop this concept in any of his philosophical works beyond this usage. It was Thomas Kuhn who explored the concept and made it a contemporary term.

Kuhn's formulation of paradigm in the The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

Scientific paradigm

The historian and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn gave this word its contemporary meaning when he adopted it to refer to the set of practices that define a scientific discipline. In his monumental work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Kuhn defines a scientific paradigm as:

- what is to be observed and scrutinized

- the kind of questions that are supposed to be asked and probed for answers in relation to this subject

- how these questions are to be structured

- how the results of scientific investigations should be interpreted

- how is an experiment to be conducted, and what equipment is available to conduct the experiment.

Thus, within normal science, paradigm is the set of exemplary experiments that are likely to be copied or emulated. The prevailing paradigm often represents a more specific way of viewing reality, or limitations on acceptable programs for future research, than the much more general scientific method.

An example of a currently accepted paradigm would be the standard model of physics. The scientific method would allow for orthodox scientific investigations of many phenomena which might contradict or disprove the standard model. The presence of the standard model has sociological implications. For example, grant funding would be more difficult to obtain for such experiments, in proportion to the amount of departure from accepted standard model theory which the experiment would test for. An experiment to test for the mass of the neutrino or decay of the proton (small departures from the model), for example, would be more likely to receive money than experiments to look for the violation of the conservation of momentum, or ways to engineer reverse time travel.

One important aspect of Kuhn's paradigms is that the paradigms are incommensurable, which means that two paradigms do not have a common standard by which one can directly compare, measure or assess competing paradigms. A new paradigm which replaces an old paradigm is not necessarily better, because the criteria of judgment depend on the paradigm.

Paradigm shifts

A scientific revolution occurs, according to Kuhn, when scientists encounter anomalies which cannot be explained by the universally accepted paradigm within which scientific progress has thereto been made. The paradigm, in Kuhn's view, is not simply the current theory, but the entire worldview in which it exists and all of the implications which come with it. There are anomalies for all paradigms, Kuhn maintained, that are brushed away as acceptable levels of error, or simply ignored and not dealt with (a principal argument Kuhn uses to reject Karl Popper's model of falsifiability as the key force involved in scientific change). Rather, according to Kuhn, anomalies have various levels of significance to the practitioners of science at the time. To put it in the context of early twentieth century physics, some scientists found the problems with calculating Mercury's perihelion more troubling than the Michelson-Morley experiment results, and some the other way around. Kuhn's model of scientific change differs here, and in many places, from that of the logical positivists in that it puts an enhanced emphasis on the individual humans involved as scientists, rather than abstracting science into a purely logical or philosophical venture.

When enough significant anomalies have accrued against a current paradigm, the scientific discipline is thrown into a state of crisis, according to Kuhn. During this crisis, new ideas, perhaps ones previously discarded, are tried. Eventually a new paradigm is formed, which gains its own new followers, and an intellectual "battle" takes place between the followers of the new paradigm and the hold-outs of the old paradigm. Again, for early twentieth-century physics, the transition between the Maxwellian electromagnetic worldview and the Einsteinian Relativistic worldview was not instantaneous nor calm, and instead involved a protracted set of "attacks," both with empirical data as well as rhetorical or philosophical arguments, by both sides, with the Einsteinian theory winning out in the long-run. Again, the weighing of evidence and importance of new data was fit through the human sieve: some scientists found the simplicity of Einstein's equations to be most compelling, while some found them more complicated than the notion of Maxwell's aether which they banished. Some found Eddington's photographs of light bending around the sun to be compelling, some questioned their accuracy and meaning. Sometimes the convincing force is just time itself and the human toll it takes, Kuhn said, using a quote from Max Planck: "a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it."

After a given discipline has changed from one paradigm to another, this is called, in Kuhn's terminology, a scientific revolution or a paradigm shift. It is often this final conclusion, the result of the long process, that is meant when the term paradigm shift is used colloquially: simply the (often radical) change of worldview, without reference to the specificities of Kuhn's historical argument.

Paradigm in social and human sciences

When Kuhn presented the concept of paradigm in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, he did not consider the concept as appropriate for the social sciences. He explains in his preface to The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that he presented the concept of paradigm precisely in order to distinguish the social from the natural sciences (p.x).[2] He wrote this book at the Palo Alto Center for Scholars, surrounded by social scientists, when he observed that they were never in agreement on theories or concepts. He explains that he wrote this book precisely to show that there are no, nor can be, any paradigms in the social sciences. Mattei Dogan, a French sociologist, in his article "Paradigms in the Social Sciences," develops Kuhn's original thesis that there are no paradigms at all in the social sciences since the concepts are polysemic, the deliberate mutual ignorance and disagreement between scholars and the proliferation of schools in these disciplines. Dogan provides many examples of the inexistence of paradigms in the social sciences in his essay,[3] particularly in sociology, political science and political anthropology.

The concept of paradigm, however, influenced not only philosophers of natural science, but also scholars in social sciences and human sciences. In these disciplines, fundamental presuppositions or a framework of thought often determine the hermeneutic horizon of scientists. The concept of paradigm appeared appropriate to describe those fundamental frameworks of thinking, if its meaning is broadly construed. In the social and human sciences, paradigms may be shared by a much narrower community of scientists who belong to the same school or share the similar perspectives. The concept of paradigm received wider acceptance and became one of the most popular terms in the late twentieth century.

The interpretive dimension of social and human sciences had been long discussed in the tradition of hermeneutics. Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911) distinguished "human sciences" or "spiritual sciences" (German: Geisteswissenschaften) from natural sciences precisely because the former is a hermeneutic discipline which requires interpretive "understanding" (German: Verstehen) while the latter give interpretation-free causal "explanation."

Kuhn's thesis that natural sciences are built upon certain socially, historically conditioned paradigms changed the standard view of natural sciences among hermeneutics as well as philosophers of natural science. Kuhn's view of natural science suggests the existence of a hermeneutic dimension of natural sciences and triggered discussion regarding the distinction of these two types of sciences.

After the seventies, Kuhn himself extended his research to hermeneutics. He realized a close affinity between natural sciences and social, human sciences. In the essay "The Natural and the Human Sciences," presented at a panel discussion with Charles Taylor in 1989,[4] Kuhn pointed out the hermeneutic dimension of natural sciences and the resemblance between natural sciences and social, human sciences. He rephrased paradigm as "hermeneutic core" in the essay. Unfortunately, Kuhn did not develop the issue further.

Notes

- ↑ Plato, The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters, Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (eds.) (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961), 1161.

- ↑ The distinction between natural sciences and human, social sciences had been discussed in the tradition of hermeneutics. Dilthey distinguished human sciences, which require interpretive understanding, whereas natural science requires non-hermeneutic, causal explanation. (see Dilthey)

- ↑ Mattei Dogan, "Paradigms in the Social Sciences," in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Volume 16, 2001.

- ↑ Kuhn presented "The Natural and the Human Sciences" at the panel discussion at LaSalle University, February 11, 1989. It was published in The Interpretative Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture (1991). The essay is also included in The Road Since Structure (2000).

See also

- Confirmation holism

- Incommensurability

- Philosophy of science

- Scientific Revolution

- Thomas Kuhn

References and Links

- Clarke, Thomas and Stewart Clegg (eds.). Changing Paradigms. London: HarperCollins, 2000.ISBN 0-00-638731-4

- Dogan, Mattei. "Paradigms in the Social Sciences," in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Volume 16, edited by Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes. New York: Elsevier Science, 2001.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. “The Natural and the Human Sciences,” in The Interpretative Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture, edited by D. Hiley, J. Bohman, and R. Shusterman, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991. (The same essay is also included in Kuhn, Thomas S., James Conant, and John Haugeland. The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970-1993, with an Autobiographical Interview. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 2002. ISBN 9780226457994

- ———. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed. Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3

- Masterman, Margaret. "The Nature of a Paradigm," pp. 59-89 in Imre Lakatos and Alan Musgrave, Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1970. ISBN 0-521-09623-5

- Plato. The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters, edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. New York: Pantheon Books, 1961.

- Von Dietze, Erich. Paradigms Explained: Rethinking Thomas Kuhn's Philosophy of Science. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2001. ISBN 9780275969998

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- Thomas Kuhn, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Historicist Theories of Rationality, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Kuhn, Thomas. IX. The Nature and Necessity of Scientific Revolutions, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.