Trubetzkoy, Nikolai

m (→Biography) |

|||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Linguists and lexicographers]] |

| − | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} | |

| − | + | {{epname|Trubetzkoy, Nikolai}} | |

| − | |||

| − | {{epname}} | ||

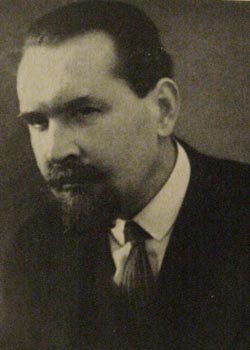

| − | + | [[Image:Nikolai Trubetzkoy.jpg|thumb|right|Nikolai Trubetzkoy, 1920s.]] | |

| − | Prince '''Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy''' ([[Russian Language|Russian]]: {{Unicode|Николай Сергеевич Трубецкой}} (or '''Nikolai Trubetzkoy''') (April 15, 1890 | + | Prince '''Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy''' ([[Russian Language|Russian]]: {{Unicode|Николай Сергеевич Трубецкой}} (or '''Nikolai Trubetzkoy''') (April 15, 1890 – June 25, 1938) was a [[Russia]]n [[linguistics|linguist]] whose teachings formed a nucleus of the [[Prague School]] of [[structuralism|structural linguistics]]. He is widely considered to be the founder of [[morphophonology]]. Trubetskoy was the son of a Russian prince and [[philosophy|philosopher]], whose [[lineage]] extended back to [[medieval]] rulers of [[Lithuania]]. In addition to his important work in linguistics, Trubetskoy formulated ideas of the development of [[Eurasia]], believing that it would inevitably become a unified entity. In a time when [[Europe]] was sharply divided, such a viewpoint was not welcome except by those (such as [[Adolf Hitler]]) who sought to dominate the whole territory by force, [[slavery|enslaving]] or exterminating any opposition. Trubetskoy rejected Hitler's [[racism|racist]] notions as the method of "unification," and suffered persecution and untimely death as a consequence. |

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| Line 12: | Line 10: | ||

[[Image:Herb Pogon Litewska.jpg|thumb|right|140px|[[Pogoń Litewska Coat of Arms]]]] | [[Image:Herb Pogon Litewska.jpg|thumb|right|140px|[[Pogoń Litewska Coat of Arms]]]] | ||

| − | Prince '''Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy''' was born on April 15, 1890 in [[Moscow]], [[Russia]] into an extremely refined environment. His father was a first-rank [[philosophy|philosopher]] whose [[lineage]] ascended to the medieval rulers of [[Lithuania]]. '''Trubetskoy''' ([[English language|English]]), '''Трубецкой''' ([[Russian language|Russian]]), '''Troubetzkoy''' ([[French language|French]]), '''Trubetzkoy''' ([[German language|German]]), '''Trubetsky''' ([[Ruthenian language|Ruthenian]]), '''Trubecki''' ([[Polish language|Polish]]), or '''Trubiacki''' ([[Belarusian language|Belarusian]]), is a typical [[Ruthenia]]n [[Gedyminid]] [[gentry]] family of [[Black Ruthenia]]n stock | + | Prince '''Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy''' was born on April 15, 1890 in [[Moscow]], [[Russia]] into an extremely refined environment. His father was a first-rank [[philosophy|philosopher]] whose [[lineage]] ascended to the medieval rulers of [[Lithuania]]. '''Trubetskoy''' ([[English language|English]]), '''Трубецкой''' ([[Russian language|Russian]]), '''Troubetzkoy''' ([[French language|French]]), '''Trubetzkoy''' ([[German language|German]]), '''Trubetsky''' ([[Ruthenian language|Ruthenian]]), '''Trubecki''' ([[Polish language|Polish]]), or '''Trubiacki''' ([[Belarusian language|Belarusian]]), is a typical [[Ruthenia]]n [[Gedyminid]] [[gentry]] family of [[Black Ruthenia]]n stock. Like many other princely houses of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, they were later prominent in Russian [[history]], [[science]], and [[arts]]. |

| − | The family descended from [[Algirdas|Olgierd]]'s son [[Demetrius I Starshiy]] (1327 | + | The noble family descended from [[Algirdas|Olgierd]]'s son [[Demetrius I Starshiy]] (1327 – May 1399 who died at the [[Battle of the Vorskla River]]). Olgierd was ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1345 to 1377, creating a vast [[empire]] stretching from the [[Baltics]] to the [[Black Sea]] and reaching within fifty miles of [[Moscow]]. The Trubetzkoy family used the [[Pogoń Litewska Coat of Arms]] and the [[Trubetsky Coat of Arms|Troubetzkoy Coat of Arms]]. Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy was born as the eighteenth generation after Demetrius I. |

| − | Having graduated from | + | Having graduated from [[Moscow University]] (1913), Trubetskoy delivered lectures there until the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|revolution in 1917]]. Thereafter he moved first to the university of [[Rostov-na-Donu]], then to the university of [[Sofia]] (1920–22), and finally took the chair of Professor of Slavic Philology at the [[University of Vienna]] (1922–1938). On settling in [[Vienna]], he became a geographically distant member of the [[Prague Linguistic School]]. |

| − | He died in 1938 in Vienna, from a [[heart attack]] attributed to [[Nazism|Nazi]] persecution following his publishing an article highly critical of [[Adolf Hitler]]'s theories. | + | He died in 1938 in Vienna, from a [[heart attack]] attributed to [[Nazism|Nazi]] persecution following his publishing of an article highly critical of [[Adolf Hitler]]'s theories. |

==Work== | ==Work== | ||

| − | Trubetzkoy's chief contributions to [[linguistics]] lie in the domain of [[phonology]], particularly in analyses of the phonological systems of individual [[language]]s and in search for general and universal phonological laws. His magnum opus, ''Grundzüge der Phonologie'' | + | Trubetzkoy's chief contributions to [[linguistics]] lie in the domain of [[phonology]], particularly in analyses of the phonological systems of individual [[language]]s and in search for general and universal phonological laws. His magnum opus, ''Grundzüge der Phonologie'' ''(Principles of Phonology),'' was issued posthumously and translated into virtually all main [[Europe]]an and [[Asia]]n languages. In this book he famously defined the [[phoneme]] as the smallest distinctive unit within the structure of a given language. This work was crucial in establishing phonology as a discipline separate from [[phonetics]]. |

Trubetzkoy considered each system in its own right, but was also crucially concerned with establishing universal explanatory laws of phonological organization (such as the symmetrical patterning in [[vowel]] systems), and his work involves the discussion of hundreds of languages, including their [[prosody]]. | Trubetzkoy considered each system in its own right, but was also crucially concerned with establishing universal explanatory laws of phonological organization (such as the symmetrical patterning in [[vowel]] systems), and his work involves the discussion of hundreds of languages, including their [[prosody]]. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 27: | ||

===''Principles of Phonology''=== | ===''Principles of Phonology''=== | ||

| − | ''Principles of Phonology'' summarized Trubetzkoy's previous [[phonology|phonological]] work and stands as the classic statement of the [[Prague Linguistic School]]'s phonology, setting out an array of ideas, several of which still characterize the debate on phonological representations. Through the ''Principles'' | + | ''Principles of Phonology'' summarized Trubetzkoy's previous [[phonology|phonological]] work and stands as the classic statement of the [[Prague Linguistic School]]'s phonology, setting out an array of ideas, several of which still characterize the debate on phonological representations. Through the ''Principles,'' the publications that preceded it, his work at conferences, and his general enthusiastic networking, Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of phonology as a discipline distinct from [[phonetics]]. |

| − | Whereas phonetics is about the physical production and [[perception]] of the [[sound]]s of [[speech]], phonology describes the way sounds function within a given [[language]] or across languages. As | + | Whereas phonetics is about the physical production and [[perception]] of the [[sound]]s of [[speech]], phonology describes the way sounds function within a given [[language]] or across languages. As phonetics is a cross-language discipline, it is only fitting that Trubetzkoy is credited with the change in phonological focus from diachrony (how languages change over [[time]]) to synchrony (study at a particular point in time, the only way to massage a lot of data from various languages without the time reference). Hence, he argued that form (contrast, systemic patterning) must be studied separately from substance (acoustics, articulation), although he did not see the two as completely separate, unlike some of his colleagues, such as [[Louis Hjelmslev]] (Trubetzkoy 1936). |

| − | Phonology, Trubetzkoy argued, should deal with the linguistic function of sounds (their ability to signal differences in word-meaning), as members of phonemic oppositions. The phoneme was his smallest phonological unit, as "oppositions" existed only within a language’s system. Thus he | + | Phonology, Trubetzkoy argued, should deal with the linguistic function of sounds (their ability to signal differences in word-meaning), as members of phonemic oppositions. The phoneme was his smallest phonological unit, as "oppositions" existed only within a language’s system. Thus he did not regard them as autonomous segmental building blocks, which they later became as the "distinctive features" of [[Roman Jakobson]]. |

Trubetzkoy is also, and above all, the founder of [[morphophonology]], the branch of linguistics that studies the phonological structure of [[morpheme]]s, the smallest lingual unit that carries a [[semantics|semantic]] interpretation. Morphophonology, as defined by Trubetzkoy, refers to the way morphemes affect each other's [[pronunciation]] (Trubetzkoy 1939). | Trubetzkoy is also, and above all, the founder of [[morphophonology]], the branch of linguistics that studies the phonological structure of [[morpheme]]s, the smallest lingual unit that carries a [[semantics|semantic]] interpretation. Morphophonology, as defined by Trubetzkoy, refers to the way morphemes affect each other's [[pronunciation]] (Trubetzkoy 1939). | ||

| Line 41: | Line 39: | ||

===Trubetzkoy vs. Saussure=== | ===Trubetzkoy vs. Saussure=== | ||

| − | Trubetzkoy, being basically [[Ferdinand de Saussure]]’s second generation follower (albeit affected by the [[Prague Linguistic School]] whose members regarded it as their "destiny" to remake Saussure for the real world), believed, as many linguists have since, that | + | Trubetzkoy, being basically [[Ferdinand de Saussure]]’s second-generation follower (albeit affected by the [[Prague Linguistic School]] whose members regarded it as their "destiny" to remake Saussure for the real world), believed, as many linguists have since, that a significant problem with Saussure’s major work may lie with a certain “staleness” and the need for Saussure's work to be open to major discussions and improvements. Part of this problem can be identified as stemming from the two students who did not add Saussure’s later ideas and concepts into the publication, rather than weaknesses in Saussure's own thinking. |

| − | Hence, in one of his letters to [[Roman Jakobson]] he wrote “For inspiration I have reread de Saussure, but on a second reading he impresses me much less. ... There is comparatively little in the book that is of value; most of it is old rubbish. And what is valuable is awfully abstract, without details.”(Trubetzkoy 2001) | + | Hence, in one of his letters to [[Roman Jakobson]] he wrote: “For inspiration I have reread de Saussure, but on a second reading he impresses me much less.... There is comparatively little in the book that is of value; most of it is old rubbish. And what is valuable is awfully abstract, without details.” (Trubetzkoy 2001) |

===''Europe and Mankind''=== | ===''Europe and Mankind''=== | ||

| − | ''Europe and Mankind'' is Trubetzkoy's other, non-linguistic, serious interest, which historically preceded ''Principles'' | + | ''Europe and Mankind'' is Trubetzkoy's other, non-linguistic, serious interest, which historically preceded ''Principles.'' As an introduction, his famous credo serves a good stead here: |

| − | :''By its very nature Eurasia is historically destined to comprise a single state entity'' (Trubetzkoy 1991) | + | :''By its very nature Eurasia is historically destined to comprise a single state entity.'' (Trubetzkoy 1991) |

| − | Trubetzkoy apparently denies any meaningful [[politics|political]] substance to the relations between [[Europe]]an states. For him, they form a single political entity, | + | Trubetzkoy apparently denies any meaningful [[politics|political]] substance to the relations between [[Europe]]an states. For him, they form a single political entity, though subdivided [[culture|culturally]], driven by Pan-European [[chauvinism]] constituted through a combination of self-interest and a European mission to "civilize." |

Trubetzkoy’s position is often couched as [[cosmopolitanism]], although some critics say that, in essence, it is only another facet of chauvinism. They feel that the only viable alternative to both "Europe" and (Eurocentric) "humankind" would be an intermediate entity, similar to Europe in its intrinsic cultural diversity, but different in what makes it hang together politically. And therein lies a problem. | Trubetzkoy’s position is often couched as [[cosmopolitanism]], although some critics say that, in essence, it is only another facet of chauvinism. They feel that the only viable alternative to both "Europe" and (Eurocentric) "humankind" would be an intermediate entity, similar to Europe in its intrinsic cultural diversity, but different in what makes it hang together politically. And therein lies a problem. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 55: | ||

Whereas conventional Western middle-grounds are usually sought on the terrain of [[international law]] and customary diplomatic practices, Trubetzkoy’s alternative, Pan-Eurasian [[nationalism]], is rooted on two different levels, territorial and [[metaphysics|metaphysical]], deliberately bypassing any [[law|legal]] structures. Trubetzkoy’s history and pledge is, however, profoundly Western in its logical structure. | Whereas conventional Western middle-grounds are usually sought on the terrain of [[international law]] and customary diplomatic practices, Trubetzkoy’s alternative, Pan-Eurasian [[nationalism]], is rooted on two different levels, territorial and [[metaphysics|metaphysical]], deliberately bypassing any [[law|legal]] structures. Trubetzkoy’s history and pledge is, however, profoundly Western in its logical structure. | ||

| − | Basically, Trubetzkoy’s feelings did not differ from those of other political émigrés in the history of the civilization. He was, however, unique in his belief that he could make a difference via his Pan-Eurasian publications and speeches. Hence, characteristically, Trubetzkoy wrote in a letter to Savitskii in 1925: | + | Basically, Trubetzkoy’s feelings did not differ from those of other political émigrés in the history of the civilization. He was, however, unique in his belief that he could make a difference via his Pan-Eurasian publications and speeches. Hence, characteristically, Trubetzkoy wrote in a letter to [[Savitskii]] in 1925: |

| − | <blockquote>I am plainly terrified by what is happening to us. I feel that we have got ourselves into a swamp that, with every new step of ours, consumes us deeper and deeper. What are we writing about to each other? What are we talking about? What are we thinking about? | + | <blockquote>I am plainly terrified by what is happening to us. I feel that we have got ourselves into a swamp that, with every new step of ours, consumes us deeper and deeper. What are we writing about to each other? What are we talking about? What are we thinking about? – Only politics. We have to call things by their real name – we are politicking, living under the sign of the primacy of politics. This is death. Let us recall what We are. We – is a peculiar way of perceiving the world. And out of this peculiar perception a peculiar way of contemplating the world may grow. And from this mode of contemplation, incidentally, some political statements may be derived. But only incidentally! (Trubetzkoy 1991)</blockquote> |

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| Line 65: | Line 63: | ||

Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of [[phonology]] as a discipline distinct from [[phonetics]], and the change in phonological focus from diachrony to synchrony. He is, above all, the founder of the branch of [[linguistics]] known as [[morphophonology]], the study of the phonological structure of [[morpheme]]s. | Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of [[phonology]] as a discipline distinct from [[phonetics]], and the change in phonological focus from diachrony to synchrony. He is, above all, the founder of the branch of [[linguistics]] known as [[morphophonology]], the study of the phonological structure of [[morpheme]]s. | ||

| − | He was an internationalist, and had contact with most of the other well known thinkers in phonology of the period, including [[Edward Sapir|Sapir]], [[Louis Hjelmslev |Hjelmslev]], and [[J. R. Firth|Firth]]. He corresponded widely and was a serious organizer, aiming to work with those who agreed with him that a truly "phonological" approach was necessary. He worked to set up an International Phonology Association. | + | He was an internationalist, and had contact with most of the other well-known thinkers in phonology of the period, including [[Edward Sapir|Sapir]], [[Louis Hjelmslev |Hjelmslev]], and [[J. R. Firth|Firth]]. He corresponded widely and was a serious organizer, aiming to work with those who agreed with him that a truly "phonological" approach was necessary. He worked to set up an International Phonology Association. |

Trubetzkoy was, indeed, an internationalist in more ways than one. His Eurasian ideas and [[sociology|sociological]] treatises published throughout the 1920s and 1930s in Russian and German (some are collected and translated in Trubetzkoy 1991) preceded the ideas and themes that became seriously studied and pursued by the [[European Union]] by 80 years. | Trubetzkoy was, indeed, an internationalist in more ways than one. His Eurasian ideas and [[sociology|sociological]] treatises published throughout the 1920s and 1930s in Russian and German (some are collected and translated in Trubetzkoy 1991) preceded the ideas and themes that became seriously studied and pursued by the [[European Union]] by 80 years. | ||

| − | ==Major | + | ==Major works== |

| − | *Trubetzkoy, N. 1936. "Essai d’une théorie des oppositions phonologiques'" ''Journal de Psychologie'' 33, pp. | + | |

| − | *Trubetzkoy, N. 1939. "Grundzuege der Phonologie | + | *Trubetzkoy, N. 1936. "Essai d’une théorie des oppositions phonologiques.'" In ''Journal de Psychologie'' 33, pp. 5–18. |

| − | *Trubetzkoy, N. [1958] 1977. ''Grundzüge der Phonologie'' | + | *Trubetzkoy, N. 1939. "Grundzuege der Phonologie." In ''Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Prague'' 7. |

| + | *Trubetzkoy, N. [1949] 1986. ''Principes de phonologie'' (translated by J. Cantineau). Paris: Klincksieck. | ||

| + | *Trubetzkoy, N. [1958] 1977. ''Grundzüge der Phonologie.'' Göttingen. | ||

*Trubetzkoy, N. 1969. ''Principles of Phonology'' (translated by Ch. Baltaxe). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. | *Trubetzkoy, N. 1969. ''Principles of Phonology'' (translated by Ch. Baltaxe). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. | ||

| − | *Trubetzkoy, | + | *Trubetzkoy, N. 1991. "Europe and Mankind." In ''The Legacy of Genghis Khan and Other Essays on Russia's Identity'' (A. Liberman, editor). Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Slavic Publications. |

| − | + | *Trubetzkoy, N. 2001. ''Studies in General Linguistics and Language Structure'' (translated by Marvin Taylor and Anatoly Liberman). Duke University Press. | |

| − | *Trubetzkoy, N. 2001. ''Studies in General Linguistics and Language Structure'' | + | |

| + | ==References== | ||

| − | + | *Jakobson, Roman. 1939. "Nécrologie Nikolaj Sergejevic Trubetzkoy." In ''Acta Linguistica.'' Reprinted in Thomas Sebeok (editor). 1966. ''Portraits of Linguists.'' Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. | |

| − | *Jakobson, Roman. 1939. "Nécrologie Nikolaj Sergejevic Trubetzkoy" ''Acta Linguistica'' | + | *Jakobson, Roman, et al. (editors). 1975. ''N. S. Trubetzkoy’s Letters and Notes.'' The Hague: Mouton. |

| − | *Jakobson, Roman et al. (editors. | ||

{{Credit2|Nikolai_Trubetzkoy|70685093|Trubetskoy|72296156|}} | {{Credit2|Nikolai_Trubetzkoy|70685093|Trubetskoy|72296156|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:37, 28 October 2008

Prince Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy (Russian: Николай Сергеевич Трубецкой (or Nikolai Trubetzkoy) (April 15, 1890 – June 25, 1938) was a Russian linguist whose teachings formed a nucleus of the Prague School of structural linguistics. He is widely considered to be the founder of morphophonology. Trubetskoy was the son of a Russian prince and philosopher, whose lineage extended back to medieval rulers of Lithuania. In addition to his important work in linguistics, Trubetskoy formulated ideas of the development of Eurasia, believing that it would inevitably become a unified entity. In a time when Europe was sharply divided, such a viewpoint was not welcome except by those (such as Adolf Hitler) who sought to dominate the whole territory by force, enslaving or exterminating any opposition. Trubetskoy rejected Hitler's racist notions as the method of "unification," and suffered persecution and untimely death as a consequence.

Biography

Prince Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy was born on April 15, 1890 in Moscow, Russia into an extremely refined environment. His father was a first-rank philosopher whose lineage ascended to the medieval rulers of Lithuania. Trubetskoy (English), Трубецкой (Russian), Troubetzkoy (French), Trubetzkoy (German), Trubetsky (Ruthenian), Trubecki (Polish), or Trubiacki (Belarusian), is a typical Ruthenian Gedyminid gentry family of Black Ruthenian stock. Like many other princely houses of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, they were later prominent in Russian history, science, and arts.

The noble family descended from Olgierd's son Demetrius I Starshiy (1327 – May 1399 who died at the Battle of the Vorskla River). Olgierd was ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1345 to 1377, creating a vast empire stretching from the Baltics to the Black Sea and reaching within fifty miles of Moscow. The Trubetzkoy family used the Pogoń Litewska Coat of Arms and the Troubetzkoy Coat of Arms. Nikolay Sergeyevich Trubetskoy was born as the eighteenth generation after Demetrius I.

Having graduated from Moscow University (1913), Trubetskoy delivered lectures there until the revolution in 1917. Thereafter he moved first to the university of Rostov-na-Donu, then to the university of Sofia (1920–22), and finally took the chair of Professor of Slavic Philology at the University of Vienna (1922–1938). On settling in Vienna, he became a geographically distant member of the Prague Linguistic School.

He died in 1938 in Vienna, from a heart attack attributed to Nazi persecution following his publishing of an article highly critical of Adolf Hitler's theories.

Work

Trubetzkoy's chief contributions to linguistics lie in the domain of phonology, particularly in analyses of the phonological systems of individual languages and in search for general and universal phonological laws. His magnum opus, Grundzüge der Phonologie (Principles of Phonology), was issued posthumously and translated into virtually all main European and Asian languages. In this book he famously defined the phoneme as the smallest distinctive unit within the structure of a given language. This work was crucial in establishing phonology as a discipline separate from phonetics.

Trubetzkoy considered each system in its own right, but was also crucially concerned with establishing universal explanatory laws of phonological organization (such as the symmetrical patterning in vowel systems), and his work involves the discussion of hundreds of languages, including their prosody.

Furthermore, his principles of phonological theory have also been applied to the analysis of sign languages, in which it is argued that the same or a similar phonological system underlies both signed and spoken languages.

Principles of Phonology

Principles of Phonology summarized Trubetzkoy's previous phonological work and stands as the classic statement of the Prague Linguistic School's phonology, setting out an array of ideas, several of which still characterize the debate on phonological representations. Through the Principles, the publications that preceded it, his work at conferences, and his general enthusiastic networking, Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of phonology as a discipline distinct from phonetics.

Whereas phonetics is about the physical production and perception of the sounds of speech, phonology describes the way sounds function within a given language or across languages. As phonetics is a cross-language discipline, it is only fitting that Trubetzkoy is credited with the change in phonological focus from diachrony (how languages change over time) to synchrony (study at a particular point in time, the only way to massage a lot of data from various languages without the time reference). Hence, he argued that form (contrast, systemic patterning) must be studied separately from substance (acoustics, articulation), although he did not see the two as completely separate, unlike some of his colleagues, such as Louis Hjelmslev (Trubetzkoy 1936).

Phonology, Trubetzkoy argued, should deal with the linguistic function of sounds (their ability to signal differences in word-meaning), as members of phonemic oppositions. The phoneme was his smallest phonological unit, as "oppositions" existed only within a language’s system. Thus he did not regard them as autonomous segmental building blocks, which they later became as the "distinctive features" of Roman Jakobson.

Trubetzkoy is also, and above all, the founder of morphophonology, the branch of linguistics that studies the phonological structure of morphemes, the smallest lingual unit that carries a semantic interpretation. Morphophonology, as defined by Trubetzkoy, refers to the way morphemes affect each other's pronunciation (Trubetzkoy 1939).

Trubetzkoy also investigated the neutralization of contrast, which helped reveal segmental (un-) marked-ness, and introduced the notion of "functional load" which was later developed by André Martinet.

Trubetzkoy vs. Saussure

Trubetzkoy, being basically Ferdinand de Saussure’s second-generation follower (albeit affected by the Prague Linguistic School whose members regarded it as their "destiny" to remake Saussure for the real world), believed, as many linguists have since, that a significant problem with Saussure’s major work may lie with a certain “staleness” and the need for Saussure's work to be open to major discussions and improvements. Part of this problem can be identified as stemming from the two students who did not add Saussure’s later ideas and concepts into the publication, rather than weaknesses in Saussure's own thinking.

Hence, in one of his letters to Roman Jakobson he wrote: “For inspiration I have reread de Saussure, but on a second reading he impresses me much less.... There is comparatively little in the book that is of value; most of it is old rubbish. And what is valuable is awfully abstract, without details.” (Trubetzkoy 2001)

Europe and Mankind

Europe and Mankind is Trubetzkoy's other, non-linguistic, serious interest, which historically preceded Principles. As an introduction, his famous credo serves a good stead here:

- By its very nature Eurasia is historically destined to comprise a single state entity. (Trubetzkoy 1991)

Trubetzkoy apparently denies any meaningful political substance to the relations between European states. For him, they form a single political entity, though subdivided culturally, driven by Pan-European chauvinism constituted through a combination of self-interest and a European mission to "civilize."

Trubetzkoy’s position is often couched as cosmopolitanism, although some critics say that, in essence, it is only another facet of chauvinism. They feel that the only viable alternative to both "Europe" and (Eurocentric) "humankind" would be an intermediate entity, similar to Europe in its intrinsic cultural diversity, but different in what makes it hang together politically. And therein lies a problem.

Whereas conventional Western middle-grounds are usually sought on the terrain of international law and customary diplomatic practices, Trubetzkoy’s alternative, Pan-Eurasian nationalism, is rooted on two different levels, territorial and metaphysical, deliberately bypassing any legal structures. Trubetzkoy’s history and pledge is, however, profoundly Western in its logical structure.

Basically, Trubetzkoy’s feelings did not differ from those of other political émigrés in the history of the civilization. He was, however, unique in his belief that he could make a difference via his Pan-Eurasian publications and speeches. Hence, characteristically, Trubetzkoy wrote in a letter to Savitskii in 1925:

I am plainly terrified by what is happening to us. I feel that we have got ourselves into a swamp that, with every new step of ours, consumes us deeper and deeper. What are we writing about to each other? What are we talking about? What are we thinking about? – Only politics. We have to call things by their real name – we are politicking, living under the sign of the primacy of politics. This is death. Let us recall what We are. We – is a peculiar way of perceiving the world. And out of this peculiar perception a peculiar way of contemplating the world may grow. And from this mode of contemplation, incidentally, some political statements may be derived. But only incidentally! (Trubetzkoy 1991)

Legacy

Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of phonology as a discipline distinct from phonetics, and the change in phonological focus from diachrony to synchrony. He is, above all, the founder of the branch of linguistics known as morphophonology, the study of the phonological structure of morphemes.

He was an internationalist, and had contact with most of the other well-known thinkers in phonology of the period, including Sapir, Hjelmslev, and Firth. He corresponded widely and was a serious organizer, aiming to work with those who agreed with him that a truly "phonological" approach was necessary. He worked to set up an International Phonology Association.

Trubetzkoy was, indeed, an internationalist in more ways than one. His Eurasian ideas and sociological treatises published throughout the 1920s and 1930s in Russian and German (some are collected and translated in Trubetzkoy 1991) preceded the ideas and themes that became seriously studied and pursued by the European Union by 80 years.

Major works

- Trubetzkoy, N. 1936. "Essai d’une théorie des oppositions phonologiques.'" In Journal de Psychologie 33, pp. 5–18.

- Trubetzkoy, N. 1939. "Grundzuege der Phonologie." In Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Prague 7.

- Trubetzkoy, N. [1949] 1986. Principes de phonologie (translated by J. Cantineau). Paris: Klincksieck.

- Trubetzkoy, N. [1958] 1977. Grundzüge der Phonologie. Göttingen.

- Trubetzkoy, N. 1969. Principles of Phonology (translated by Ch. Baltaxe). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Trubetzkoy, N. 1991. "Europe and Mankind." In The Legacy of Genghis Khan and Other Essays on Russia's Identity (A. Liberman, editor). Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Slavic Publications.

- Trubetzkoy, N. 2001. Studies in General Linguistics and Language Structure (translated by Marvin Taylor and Anatoly Liberman). Duke University Press.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Jakobson, Roman. 1939. "Nécrologie Nikolaj Sergejevic Trubetzkoy." In Acta Linguistica. Reprinted in Thomas Sebeok (editor). 1966. Portraits of Linguists. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Jakobson, Roman, et al. (editors). 1975. N. S. Trubetzkoy’s Letters and Notes. The Hague: Mouton.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.