Difference between revisions of "Navajo" - New World Encyclopedia

(→Hogans) |

|||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

[[Image:Hogan Navajo.jpg |thumb|left|160px|Navajo hogan]] | [[Image:Hogan Navajo.jpg |thumb|left|160px|Navajo hogan]] | ||

| − | A [[hogan]] is the traditional Navajo home. For those who practice the Navajo religion the hogan is considered sacred. The religious song "[[The Blessingway]]" describes the first hogan as being built by Coyote with help from beavers to be a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Today they are rarely used as actual dwellings, but are maintained primarily for ceremonial purposes. | + | A [[hogan]] is the traditional Navajo home. For those who practice the Navajo religion the hogan is considered sacred. Hogans are sacred and constructed to symbolize their land: the four posts represent the sacred mountains, the floor is mother earth, and the dome-like roof is father sky. The religious song "[[The Blessingway]]" describes the first hogan as being built by Coyote with help from beavers to be a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Today they are rarely used as actual dwellings, but are maintained primarily for ceremonial purposes. |

===Arts and craftsmanship=== | ===Arts and craftsmanship=== | ||

Revision as of 17:00, 11 October 2007

| Navajo (Diné) |

|---|

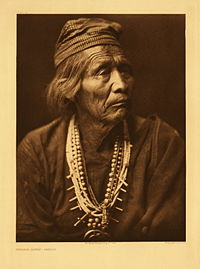

| Navajo medicine man |

| Total population |

| 338,443 (2005 census) |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, California and Northern Mexico) |

| Languages |

| Navajo, English, Spanish |

| Religions |

| Navajo way, Christianity, Native American Church (NAC), other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Southern Athabascan peoples |

The Navajo (also Navaho) people of the southwestern United States call themselves the Diné (pronounced [dɪnɛ]), which roughly means "the people." They speak the Navajo language, and many are members of the Navajo Nation, an independent government structure which manages the Navajo reservation in the Four Corners area of the United States.

Name

The name "Navajo" comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish (Apaches de) Navajó "(Apaches of) Navajó," which was derived from the Tewa navahū "fields adjoining a ravine." The Navajo call themselves Diné, which is translated to mean "the people" (most Native American groups call themselves by names that mean "the people"). Nonetheless, most Navajo now acquiesce to being called "Navajo."

Early history

The Navajo speak dialects of the language family referred to as Athabaskan. Athabaskan speakers can also be found living in Alaska through west-central Canada and in a few areas on the Pacific coast. Linguistic and cultural similarities indicate the Navajo and the other Southern Athabaskan speakers (known today as Apaches) were once a single ethnic group (linguistically called Apachean) that probably came from the Great Slave Lake area having crossed the land bridge thousands of years previous. Archaeological and historical evidence suggests these people entered the Southwest after 1000 C.E., with substantial population increases occurring in the 1200s. The Spanish noted the presence of a significant population in the 1500s. Navajo oral traditions are said to retain references of this migration.[1]

Coronado observed Plains people ("dog nomads") wintering near the Pueblos in established camps, who may have included Navajo. In 1540 Coronado reported the modern Western Apache area as uninhabited, yet in the 1580s other Spaniards first mention Apache living west of the Rio Grande who shared corn with them. The early Athabaskan way of life complicates accurate dating, primarily because they constructed less durable dwellings than other Southwestern groups. They also left behind a more austere set of tools and material goods. Sites where early Athabaskans speakers may have lived are difficult to locate, and even more difficult to identify firmly as culturally Athabaskan.

Whenever the Navajo actually arrived, they occupied areas the Pueblos peoples had abandoned during prior centuries. The Navajo people traditionally hold the four sacred mountains as the boundaries of the homeland they should never leave: Blanca Peak (Tsisnaasjini'—Dawn or White Shell Mountain) in Colorado, Mount Taylor (Tsoodzil—Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain) in New Mexico, the San Francisco Peaks (Doko'oosliid—Abalone Shell Mountain) in Arizona, and Hesperus Mountain (Dibé Nitsaa—Big Mountain Sheep) in Colorado.

Navajo oral history seems to indicate a long relationship with Pueblo people, and a willingness to adapt ideas into their own culture. Trade between the long-established Pueblo peoples and the Athabaskans was important to both groups. The Spanish records say by the mid 1500s, the Pueblos exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, hides and material for stone tools from Athabaskans who either traveled to them or lived around them. In the 1700s the Spanish report that the Navajo had large numbers of livestock and large areas of crops. The Navajo probably adapted many Pueblo ideas, as well as practices of early Spanish settlers, into their own very different culture.

The Spanish first use the word Navajo ("Apachu de Nabajo") specifically in the 1620s, referring to the people in the Chama valley region east of the San Juan River and northwest of Santa Fe. By the 1640s, the term Navajo was applied to these same people. The Spanish recorded in 1670s they were living in a region called Dinetah, which was about sixty miles west of the Rio Chama valley region. In the 1780s the Spanish were sending military expeditions against the Navajo in the southwest and west of that area, in the Mount Taylor and Chuska Mountain regions of New Mexico.

Navajos seem to have a history in the last 1000 years of expanding their range, refining their self identity and their significance to others. In short this is probably due to a cultural combination of Endemic warfare(raids) and commerce with the Pueblo, Apache, Ute, Comanche and Spanish people, set in the changing natural environment of the Southwest.

Navajo conflicts with European invaders spanned over a 300 year period. From a Navajo perspective, Europeans were considered another tribe. Traditionally, different towns, villages or pueblos were probably viewed as separate tribes or bands by Navajo groups.

The Spanish started to establish a military force along the Rio Grande in the 1600s to the East of Dinetah (the Navajo homeland). Spanish records indicate that Apachean groups (that might include Navajo) allied themselves with the Pueblos over the next 80 years, successfully pushing the Spaniards out of this area following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Raiding and trading were part of traditional Apachean and Navajo culture, and these activities increased following the introduction of the horse by the Spaniards, which increased the efficiency and frequency of raiding expeditions. The Spanish established a series of forts that protected new Spanish settlements and also separated the Pueblos from the Apacheans. The Spaniards and later Mexicans recorded what are called punitive expeditions among the Navajo that also took livestock and human captives. The Navajo in turn raided settlements far away in a similar manner. This pattern continued, with the Athapaskan groups apparently growing to be more formidable foes through the 1840s until the American Military arrived in the area.

In 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny invaded Santa Fe with 1,600 men during the Mexican War. The Navajo did not recognize the change of government as legitimate. In September, Kearny sent two detachments to raid and subdue the Navajo. Kearny later took 300 men on an expedition to California from Santa Fe. As they traveled past Navajo homelands, his force lost livestock. He ordered another expedition against the Navajo and this resulted in the first treaty with the United States government in November at Canyon de Chelly.

In the next 10 years, the U.S. established forts in traditional Navajo territory. Military records state this was to protect citizens and Navajo from each other. However the old Spanish/Mexican-Navajo pattern of raids and expeditions against one another continued. New Mexican (citizen and militia) raids increased rapidly in 1860–61 earning it the Navajo name Naahondzood, "the fearing time."

In 1861 Brigadier-General James H. Carleton, the new commander of the Federal District of New Mexico, initiated a series of military actions against the Navajo. Colonel Kit Carson was ordered by Gen. J. H. Carleton to conduct expedition into Navajoland and receive their surrender on July 20, 1863. A few Navajo surrendered. Carson was joined by a large group of New Mexican militia volunteer citizens and these forces moved through Navajo land basically killing Navajos and making sure that any Navajo crops, livestock or dwellings were destroyed. Facing starvation, Navajos groups started to surrender in what is known as The Long Walk.

Starting in the spring of 1864, around 9,000 Navajo men, women and children were forced on The Long Walk of over 300 miles to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. This was the largest Reservation attempted by the U.S. government. It was a failure for a combination of reasons: it was designed (water, wood, supplies, livestock) for 4,000–5,000 people, it had one kind of crop failure after another, other tribes and civilians were able to raid the Navajo, a small group of Mescalero Apaches had been moved there, and there was the usual poor planning and/or corruption of the period. In 1868 a treaty was negotiated that allowed the surviving Navajos to return to a reservation that was a portion of their former range.

A Navajo Tribal Police operated between 1872 and 1875 and was used by the Navajo themeselves to stop raiders from their tribe; it was created by Manuelito. In 1883 Lt. Parker took ten enlisted men and two scouts and went up to the San Juan River to separate Navajos and citizens who encroached on Navajo land. Lt. Lockett took 42 enlisted men and no scouts, and were later joined by Lt. Holomon at Navajo Springs. Evidently citizen Houck and/or Owens had murdered a Navajo Chief's son and 100 armed Navajos were looking for them. In 1887, citizens Palmer, Lockhart and King fabricated a charge of horse thievery and attacked a random home on the reservation. Two Navajo men and all three white men died but a woman and a child survived. Capt. Kerr and two Navajo scouts examined the ground and then met with several hundred Navajo at Houcks Tank. Rancher Bennett, whose horse was allegedly stolen, pointed out to Kerr that his horses were stolen by the three white men. Lt. Scott with two scouts and 21 men headed to the San Juan River. The Navajo believed he was there to drive off the whites who had settled on the reservation, and fenced off the river from the Navajo. Scott tells them to wait. He found evidence of many ranches but only three were active and when they refused to leave, wanting payment for their improvements on the land, Scott ejected them with military muscle. In 1890, when a local rancher refused to pay the Navajo a fine of livestock, the Navajos tried to collect it peacefully. White men in southern Colorado and Utah claimed that 9,000 Navajo were on the warpath, so a small military detachment out of Ft. Wingate restored the white citizens to order. The military continued to maintain the forts. Some Navajo were employed by the military as "Indian Scouts" through 1895.

In 1913, an Indian Agent ordered a Navajo and his three wives to come in for questioning, then arrested them for having a plural marriage. A small group of Navajo use force to free the women and retreat to Beautiful Mountain with 30 or 40 sympathizers. They refuse to surrender to the Agent. Local law enforcement and military refuse the Agent's request for an armed engagement. General Scott arrives and with help of Chee Dodge defuses the situation.

By treaty, the Navajo people were allowed to leave the reservation with permission to trade. Raiding by the Navajo essentially stopped, because they were able to increase the size of their livestock and crops, and not have to risk losing them to others. However, while the initial reservation increased from 3.5 million acres (14,000 km²) to the 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of today, economic conflicts with the non-Navajo continued. Civilians and companies raided resources that had been assigned to the Navajo. Livestock grazing leases, land for railroads, mining permits are a few examples of actions taken by agencies of the U.S. government who could and did do such things on a regular basis over the next 100 years. The livestock business was so successful that eventually the United states government decided to kill off most of the livestock in what is known as the Navajo Livestock Reduction.

Regional newspapers have many accounts of Navajo and non-Navajo conflicts in this period. These conflicts were often embellished by regional politicians. In some of these accounts, every Navajo was just about to leave the reservation and pillage the country side or worse. While it is probably true that some Navajo strayed, it is equally true that some white citizens clearly strayed from the laws of the land themselves. In their reports, the U.S. Military never seemed to be that alarmed about a Navajo uprising, and they clearly did not want the Navajo stirred up by their neighbors.

Culture

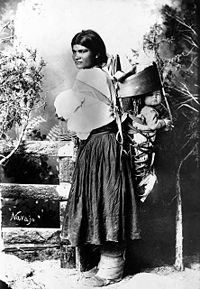

Traditionally, like other Apacheans, the Navajo were semi-nomadic in the 1500s into the 1900s. Their extended kinship groups would have seasonal dwelling areas to accommodate livestock, agriculture and gathering practices. As part of their traditional economy, Navajo groups may have formed trading or raiding parties, traveling relatively long distances.

Historically, the structure of the Navajo society is largely a matrilocal system in which only women were allowed to own livestock and land. Once married, a Navajo man would move into his bride's dwelling and clan since daughters (or, if necessary, other female relatives) were traditionally the ones who received the generational inheritance (this is mirror-opposite to a patrilocal tradition). Any children are said to belong to the mother's clan and be "born for" the father's clan. The clan system is exogamous, meaning it was, and mostly still is, considered a form of incest to marry or date anyone from any of a person's four grandparents clans.

A hogan is the traditional Navajo home. For those who practice the Navajo religion the hogan is considered sacred. Hogans are sacred and constructed to symbolize their land: the four posts represent the sacred mountains, the floor is mother earth, and the dome-like roof is father sky. The religious song "The Blessingway" describes the first hogan as being built by Coyote with help from beavers to be a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Today they are rarely used as actual dwellings, but are maintained primarily for ceremonial purposes.

Arts and craftsmanship

Silversmithing is said to have been introduced to the Navajo while in captivity at Fort Sumner in Eastern New Mexico in 1864. At that time Atsidi Saani learned the silversmithing and began teaching others the craft as well. By the 1880 Navajo silversmiths were creating handmade jewelry including bracelets, tobacco flasks, necklaces, bow guards and eventually evolved into earrings, buckles, bolos, hair ornaments and pins. Turquoise had been used with jewelry by the Navajo for hundreds of years, but they did not do turquoise inlay.

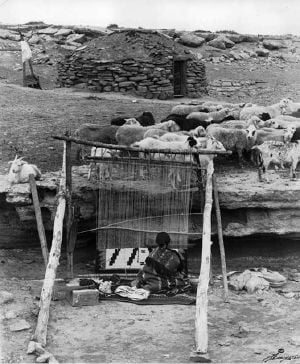

Though some people say the Navajo learned the art of weaving from the Ute, the origins of Navajo weaving may never be known. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 1700s the Navajo had begun to import yarn with their favorite color, Bayeta red. (see link below to Navajo weaving website) The Navajo people created some of the finest textiles in North America. Using an upright loom the Navajos made almost exclusively utilitarian blankets. Little patterning and few colors on almost all blankets, except for the much sought after Chief's Blanket, which evolved from the 1st Phase, few wide bands, to the 2nd phase, wide bands with squares on the corners, to the 3rd Phase, which made more and more use of patterns and colors. Around the same time the Navajo people, who had long started traded for commercial wool, often from the uniforms of soldiers, rewove these into intricate multicolored blankets called Germantown.

Some early European settlers moved in and set up trading posts, often buying Navajo Rugs by the pound and selling them back east by the bale. Still these traders encouraged the locals to weave blankets and rugs into distinct styles. They included "Two Gray Hills" (predominantly black and white, with traditional patterns), "Teec Nos Pos" (colorful, with very extensive patterns), "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell), red dominated patterns with black and white, "Crystal" (founded by J. B. Moore), oriental and Persian styles (almost always with natural dyes), "Wide Ruins," "Chinlee," banded geometric patterns, "Klagetoh," diamond type patterns, "Red Mesa" and bold diamond patterns. Many of these patterns exhibit a fourfold symmetry, which is thought by Gary Witherspoon to embody traditional ideas about harmony or Hozh.

Healing and spiritual practices

Navajo spiritual practice is about restoring health, balance, and harmony to a person's life. One exception to the concept of healing is the Beauty Way ceremony: the Kinaaldá, or a female puberty ceremony. Others include the Hooghan Blessing Ceremony and the "Baby's First Laugh Ceremony." Otherwise, ceremonies are used to heal illnesses, strengthen weakness, and give vitality to the patient. Ceremonies restore Hozhò, or beauty, harmony, balance, and health.

When suffering from illness or injury, Navajos will traditionally seek out a certified, credible Hatałii (medicine man) for healing, before turning to Western medicine (e.g., hospitals). The medicine man will use several methods to diagnose the patient's ailments. This may include using special tools such as crystal rocks, and abilities such as hand-trembling and Hatał (chanting prayer). The medicine man will then select a specific healing chant for that type of ailment. Short blessings for good luck and protection may only take a few hours, and in all cases, the patient is expected to do a follow-up afterwards. This may include the avoidance of sexual relations, personal contact, animals, certain foods, and certain activities; it is not unlike a doctor's advice. This is done to respect the ceremony.

Possible causes of ailments could be the result of violating taboos. Contact with lightning-struck objects, exposure to taboo animals such as snakes, and contact with the dead are some of reasons for healing. Protection ceremonies, especially the Blessing Way Ceremony, are used for Navajos that leave the boundaries of the four sacred mountains, and is used extensively for Navajo soldiers going to war. Upon re-entry, there is an Enemy Way Ceremony, or Nidáá', performed on the person, to get rid of the evil things in his/her body, and to restore balance in their lives. This is also important for Navajo soldiers returning from war; many soldiers, whether or not they are Navajo, often suffer psychological damage, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, from participating in warfare, and the Enemy Way Ceremony helps heal their damaged minds.

There are also ceremonies used for curing people from curses. Many people often complain of witches and skin-walkers that do harm to their minds, bodies, and even families. Ailments aren't necessarily physical. It can take any form it wishes. The medicine man is often able to break the curses that witches and skin-walkers put on families. Mild cases do not take very long, but for extreme cases, special ceremonies are needed to drive away the evil spirits. In these cases, the medicine man may find curse objects implanted inside the victim's body. These objects are used to cause the person pain and illness. Examples of such objects include bone fragments, rocks and pebbles, bits of string, snake teeth, owl feathers, and even turquoise jewelry.

There are said to be approximately fifty-eight to sixty sacred ceremonies. Most of them last four days or more; to be most effective, they require that relatives and friends attend and help out. Outsiders are often discouraged from participating, in case they become a burden on everyone, or violate a taboo. This could affect the turnout of the ceremony. The ceremony must be done in precisely the correct manner to heal the patient, and this includes everyone that is involved.

Medicine men must be able to correctly perform a ceremony from beginning to end. If he does not, the ceremony will not work. Training a Hatałii to perform ceremonies is extensive, arduous, and takes many years, and is not unlike priesthood, with the governing body or hierarchy omitted. The apprentice learns everything by watching his teacher, and memorizes the words to all the chants. Many times, a medicine man cannot learn all sixty of the ceremonies, so he will opt to specialize in a select few.

The origin of spiritual healing ceremonies dates back to Navajo mythology. It is said the first Enemy Way ceremony was performed for Changing Woman's twin sons (Monster Slayer and Born-For-the-Water) after slaying the Giants (the Yé'ii) and restoring Hozhó to the world and people. The patient identifies with Monster Slayer through the chants, prayers, sandpaintings, herbal medicine and dance.

Another Navajo healing, the Night Chant ceremony, is administered as a cure for most types of head ailments, including mental disturbances. The ceremony, conducted over several days, involves purification, evocation of the gods, identification between the patient and the gods, and the transformation of the patient. Each day entails the performance of certain rites and the creation of detailed sand paintings. On the ninth evening a final all-night ceremony occurs, in which the dark male thunderbird god is evoked in a song that starts by describing his home:

- In Tsegihi [White House],

- In the house made of the dawn,

- In the house made of the evening light

- (Sandner, p. 88)

The medicine man proceeds by asking the Holy People to be present, then identifying the patient with the power of the god and describing the patient's transformation to renewed health with lines such as "Happily I recover." (Sandner, p. 90). The same dance is repeated throughout the night, about forty eight times. Altogether the Night Chant ceremony takes about ten hours to perform, and ends at dawn.

Religion

Creation story

The Navajo creation story centers on the area known as the Dinetah, the traditional homeland of the Navajo people.

The basic outline of the Navajo creation story is as follows:

Holy Supreme Wind being created the mists of lights arose through the darkness to animate and bring purpose to the myriad Holy People, supernatural and sacred in the different three lower worlds.

All these things were spiritually created in the time before the earth existed and the physical aspect of man did not exist yet, but the spiritual did. In the first world the insect people started fighting with one another and were instructed by the Holy People to depart.

They journeyed to the second world and lived for a time in peace, but eventually they fought with each other and were instructed to depart.

In the third world the same thing happens again and they are forced to journey to the fourth world.

In the fourth world, they found the Hopi living there and succeeded in not fighting with one another or their neighbors, and their bodies were transformed from the insect forms to human forms. Eventually however, they fought with each other again, and again were instructed to depart.

They journeyed to the fifth world and succeeded in not fighting with one another and their bodies were transformed from the insect forms to human forms

First man and First woman physically appear here formed from ears of white and yellow corn, but they were also created back in the beginning. There is a separation of male and female humans because each did not appreciate the contributions of the other, and this laid the groundwork for the appearance of the Monsters that would start to kill off the people in the next world.

Coyote also appears and steals the baby of water monster, who brings a great flood in the third world which primarily forces the humans as well as Holy People to journey to the surface of the fifth world through a hollow reed. Some things are left behind and some things are brought to help the people re-create the world each time they entered a new one. Death and the Monsters are born into this world as is Changing Woman who gives birth to the Hero Twins, called "Monster Slayer" and "Child of the Waters" who had many adventures in which they helped to rid the world of much evil. Earth Surface People, mortals, were created in the fourth world, and the gods gave them ceremonies which are still practiced today.

This origin myth forms the basis for the traditional Navajo way of life.

Dieties

The meanings embodied by the named deities below are described individually, but these belong within an overall belief system. A useful way of understanding this belief system is via the concept of "iinaa ji" (Life Way or Beauty Way), i.e. the correct progress through life. In iinaa ji the goal is to live a long life in happiness. To attain this goal, man is given resources in the form of family, social, cultural, religious, educational and political teachings to shape a person into a dignified human being. Woman receives help from the family in giving birth and taking care of the infant. The child needs discipline, guidance and teaching. In adolescence there are teachings and ceremonies showing how people should interact with one another, and which (e.g.) initiate a girl into womanhood. In old age, the person will be cared for within family and society in accordance with religious teachings. By continually striving to live life in beauty and harmony, the individual having lived their life according to the tenets of iinaa ji, will have "lived a long life into old age in beautiful happiness" not only for themselves but for others around them. The ceremonial knowledge embodied by the deities are intended to be used to promote the positive aspects of iinaa ji.

The mythical beings discussed here are representations of the opposing forces of creation and destruction. They are neither good or evil because within creation both disparate representations must work in harmonious balance in order for the world to function. This idea of balance and the maintenance of it is central to Navajo mythology.

Díyín diné’é (Holy People)

The Díyín diné’é (Holy People) are the whole corpus of supernatural beings that reside within the myriad outward expressions of creation, "one who lies [lays] within it," and they have varying degrees of supernatural powers [2]. They outwardly express themselves to interact with human beings by taking on human forms or through representations in the context of animating forces that reside inside of the natural forces found in nature, plants, animals, prophets, and cultural heroes through the ceremonies. The díyín diné were animated and given their purpose in creation by "Supreme Sacred Wind" who first express itself out of the darkness.[3]

- Áłtsé hastiin (First Man) - Created by the Holy People and given the dual creative and destructive powers of creation to create and bring about the world as it exists today. He works in conjunction with First Woman and is considered part of the díyín diné’é.

- Áłtsé asdząąn (First Woman) - Created by the Holy People and given the dual creataive destructive powers of creation to create and bring about the world as it exists today. She worked in conjunction with First Man and is considered part of the díyín diné’é.

- Áłtsé hashké (First Scolder) or Mą'ii (Roamer / Coyote) - Generally regarded as the trickster, but who hangs around First Man and First Woman and through his foolish actions reveals the limitations of the spiritual and material realities and the consequences of transgressing them. He is the unwitting agent of First Man's and First Woman's creation designs and yet coyote is considered as a very dangerous entity because of his irresponsible and foolish application of his acquired and limited knowledge of the dual creative and destructive powers of creation, for his own personal egotistical gain. The consequences of his lack of foresight in the wielding these powers also applies to actions started at the material level of creation. Considered a Díyín diné’é.

- Jóhonaa’éí (Sun Bearer) could be considered a solar deity who carries the sun across the sky on his back and stores it in the west side of his house during the night. It can also be considered as the force that gives and represents the sun's purpose in creation, ie. moving it through and across the sky. The object sun "so'" is not johona'ai, but johona'ai is the force, animating principle and purpose that resides within the sun and also gives life to all creation on the surface of the earth. Supreme Sacred Wind indirectly created so' through the interaction of other created phenomena, as well as Johona'ai.

- Yoołgai asdząąn (White-shell Woman) can be considered a lunar deity associated with the seasons. She can be considered the sister of Changing Woman, but the two are also considered as being one and the same. Her name comes from her creation, since she was made from abalone shell. She is associated with the ocean, the sunrise, fire, and maize.

- Asdząąn nádleehé (Changing Woman) - She can be viewed as the sister of White-shell Woman, or the very same as White-shell Woman. She was a sky goddess who was very respected among the Navajo. She was also a goddess of change, particularly the maturation of women. She grows with the days and seasons cyclically from a young maiden to an adult woman to an old crone, endlessly without dying. She helped in creating humans and now rules over the powers of creation, given in the underworld to First Man and First Woman, who in turn passed them on to Changing Woman for the maintenance of this world. She was raised by First Man and First woman after they saw a black cloud on a mountain for four days, and upon investigating it discovered the infant Changing Woman, who grew from infant to an adult woman in eighteen days. Later she gave birth to the Twin warrior gods who slew the monsters who were killing the Diné. After departing to live in her home towards the western ocean, she increased the number of humans by creating more people out of small pieces of her skin because she was lonely and wanted companions.

Practices

Four Sacred Mountains

The Navajo religion is distinct in that is must be practiced in a particular geographical area, known as the Dinetah (the traditional Navajo homeland). Navajo people believe that the creator instructed them never to leave the land between four sacred mountains located in Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona.

To the south is Mount Taylor; to the west are the San Francisco Peaks; to the east is Blanca Peak, and to the north is Hesperus Peak. There is a sacred object and a color representing each of the four cardinal directions. To the east is the white morning sky; its precious stone is white shell. To the south is blue and turquoise. To the west is yellow, and the corresponding stone is yellow abalone. To the north is black and jet.[4]

Witches

There are a number of beliefs in traditional Navajo culture relating to practices which, in English, are all referred to as 'witchcraft.' In the Navajo language, they are actually each referred to distinctly, and are regarded as separate, albeit related, phenomena.

The practices lumped together in the category 'witchcraft' are very similar, at least in their externals, to the rituals practiced on the 'good side' of Navajo tradition, the ceremonials or 'sings'. The difference, however, is that while the good sings are to heal or bring luck, the bad ones are intended to hurt and curse. Similarly, all kinds of witches are associated with transgression of taboos and societal standards, especially those relating to family and the dead.

Witchery Way: ’áńt’įįzhį

This is the most common type of witchcraft, centering around the Witchery or Corpse-poison Way—’áńt’įįzhį. The Witchery Way is recorded in the Emergence Story as having been invented by First Man and First Woman, so it goes back to the dawn of the human race. Practitioners of Witchery Way are called ’ánt’įįhnii, "witch people."

’Ánt’įįhnii usually learn their art from a parent or grandparent, but sometimes from a spouse. Most witches are male; it is sometimes thought that the only women who become witches are old and childless. The initiation into the Witchery Way involves murdering a close relative, especially a sibling; other crimes associated with it are necrophilia, grave-robbing, and incest. Being suspected of any of these is tantamount to also being a witch, and suspected witches are automatically suspected of the other crimes, as well.

The method of Witchery Way centers around powdered corpses, known as ’áńt’į "corpse poison," (literally, Witchery or Harming). The best sources for ’áńt’į are the corpses of children, especially twins; the best body parts for it are the fingerprints and the bones of the back of the skull. ’Áńt’į is said to look like the corn pollen used in blessing ceremonials. However, it is used to curse, not to bless.

The effect of the ’áńt’į is a curse-disease, usually indicated by an immediate reaction to administration of the poison, like fainting, swelling of the tongue, or lockjaw. Sometimes, however, the victims simply wastes away as from a normal disease. Because, however, it is actually caused by a witch, medicine or the usual disease ceremonials will not be effective.

These witches are also associated with dark ceremonials of their own, where they plan and perform their spells and initiations. The witches gather in a cave or other secluded spot, called the ’áńt’įbáhoołan, usually going in animal form (see below). Once there, they resume their human form, naked except for masks, jewelry, and paint like that used in normal ceremonies. They sit in a circle, surrounded by their supply of corpse-flesh and severed heads, and perform their ceremonies, essentially a corrupted form of a good sing (rather like the European idea of the Black Mass). As at a regular ceremonial, they sing and create sand-paintings, except that witches' paintings use ash, not sand. Other activities at the "witches' sing" include necrophilia and cannibalism.

’Ánt’įįhnii are the witches who become the famous Navajo shape-shifters, the Skin-walkers. They use the animal forms they can assume to travel surreptitiously to the ’áńt’įbáhoołan, and to deliver their ’áńt’į in secret. Frequently, the words yee naaldlooshii and ’ánt’įįhnii are used interchangeably.

Sympathetic magic, 'voodoo': ’iińzhįįd

Usually considered a sub-branch of Witchery Way, ’iińzhįįd (literally, "evil-wishing magic") is not based on the corpse-poison, but on the power of names, body material like fingernails, and possessions to affect their owners; it is a practice that revolves around sympathetic magic and curses. Some practitioners are said to have a "power," like sun, lightning, snakes, etc., that helps; besides humans, some animals, especially dogs, are said to use ’iińzhįįd, as are whirlwinds. Though people are the most typical targets, animals, crops, automobiles, and other property are sometimes cursed, as well.

The first step in bewitching someone this way is obtaining an article of clothing or a piece of the body, like hair, fingernails, or excrement. The item is then buried with corpse flesh, in a grave, or under a tree that has been struck by lightning, and then an incantation is said or sung—frequently a benevolent prayer backwards, as in European tradition. The Béésh ńghiz or Hard Flint song is sometimes used, as is a prayer called "Praying a person down into the ground." Also used are the prayers "The Two Came to Their Father" (Hataa’ baazhná’ázhi), relating to the mythical Hero Twins, and the "It became dead!"(Ni’iisįįd), said to have been composed by First Man. Either the time between the spellcasting and the victim's death is specified in the chant, or the victim dies in four days.

Other techniques are used, too. When the target is a pregnant woman, the body of a horned toad is cut open, and the personal effect is placed inside the cavity, and then the chant is said. As in other witchcraft traditions, walking around the victim's house or stepping over him while he sleeps can inflict an ’iińzhįįd curse. Unique to the Navajo, however, an ’iikááh bee’onozhin or "Curse-sandpainting" is also used, as at the Witches' Sing. Unlike there, though, the ’iikááh bee’onozhin associated with ’iińzhįįd is created in solitude, and always to the north (the direction of evil) of a hogan.

It is possible that the Navajo custom of having two names, one a "War-Name" given by one's grandparents and rarely used except for very specific purposes, the other essentially a nickname used in day-to-day life, may have come from fear of ’iińzhįįd.

Curse objects: ’adagąsh

This kind of witchcraft involves injecting cursed objects, like beads, into people or things.

Charms, Frenzy Way: ’azhįįtee

This kind of witchcraft involves magically influencing the minds and emotions of others.

Skin-walkers

In Native American and Norse legend, a skin-walker is a person with the supernatural ability to turn into any animal he or she desires. Similar creatures can be found in numerous cultures' lores all over the world, closely related to beliefs in werewolves (also known as lycanthropes) and other "were" creatures (which can be described as therianthropes).

Possibly the best documented skin-walker beliefs are those relating to the Navajo Yea-Naa-gloo-shee (literally "with it, he goes on all fours" in the Navajo language). A Yea-Naa-gloo-shee is one of the several varieties of Navajo witch (specifically an ’ánt’įįhnii or practitioner of the Witchery Way, as opposed to a user of curse-objects (’adagąsh) or a practitioner of Frenzy Way (’azhįtee)). Technically, the term refers to an ’ánt’įįhnii who is using his (rarely her) powers to travel in animal form. In some versions men or women who have attained the highest level of priesthood then commit the act of killing an immediate member of their family, and then have thus gained the evil powers that are associated with skin-walkers.

The ’ánt’įįhnii are human beings who have gained supernatural power by breaking a cultural taboo. Specifically, a person is said to gain the power to become a Yea-Naa-gloo-shee upon initiation into the Witchery Way. Both men and women can become ’ánt’įįhnii and therefore possibly skinwalkers, but men are far more numerous. It is generally thought that only childless women can become witches.

Although it is most frequently seen as a coyote, wolf, owl, fox, or crow, the Yea-Naa-gloo-shee is said to have the power to assume the form of any animal they choose, depending on what kind of abilities they need. Witches use the form for expedient travel, especially to the Navajo equivalent of the 'Black Mass', a perverted sing (and the central rite of the Witchery Way) used to curse instead of to heal. They also may transform to escape from pursuers.

Some Navajo also believe that skin-walkers have the ability to steal the "skin" or body of a person. The Navajo believe that if you lock eyes with a skin walker they can absorb themselves into your body. It is also said that skin walkers avoid the light and that their eyes glow like an animal's when in human form and when in animal form their eyes do not glow as an animal's would.

A skin-walker is usually described as naked, except for a coyote skin, or wolf skin. Some Navajos describe them as a mutated version of the animal in question. The skin may just be a mask, like those which are the only garment worn in the witches' sing.

Because animal skins are used primarily by skin-walkers, the pelt of animals such as bears, coyotes, wolves, and cougars are strictly tabooed. Sheepskin and buckskin are probably two of the few hides used by Navajos, the latter is used only for ceremonial purposes.

Often, Navajos tell of their encounter with a skin-walker, though there may be some hesitancy to reveal the story to non-Navajos, or (understandably) to talk of such frightening things at night. Sometimes the skin-walker will try to break into the house and attack the people inside, and will often bang on the walls of the house, knock on the windows, and climb onto the roofs. Sometimes, a strange, animal-like figure is seen standing outside the window, peering in. Other times, a skinwalker may attack a vehicle and cause a car accident. The skin-walkers are described as being fast, agile, and impossible to catch. Though some attempts have been made to shoot or kill one, they are not usually successful. Sometimes a skinwalker will be tracked down, only to lead to the house of someone known to the tracker. As in European werewolf lore, sometimes a wounded skinwalker will escape, only to have someone turn up later with a similar wound which reveals them to be the witch. It is said that if a Navajo was to know the person behind the skinwalker they had to pronounce the full name. And about three days later that person would either get sick or die for the wrong that they have committed.[5]

According to Navajo legend, skin-walkers can have the power to read human thoughts. They also possess the ability to make any human or animal noise they choose. A skinwalker may use the voice of a relative or the cry of an infant to lure victims out of the safety of their homes.

The legend of the skin-walker tell of god giving the people a gift of transformation and was used only against their enemies. Over time, the people began to abuse this power, thus bringing god to earth to reclaim it. Some gave the power up and others hid with it and passed the knowledge to others.

Some tribes believe that skin-walkers can use the spit, hair, or shoes and old clothing of a person to make curses that will attack that specific person. For this reason many Navajo will never spit or leave shoes outside. They also take great care to see that any hair or nail clippings are burned. Urine cannot endanger a person because it is considered too acidic.

Traditional Navajo music is always vocal, with most instruments, which include drums, drumsticks, rattles, rasp, flute, whistle, and bullroarer, being used to accompany singing of specific types of song (Frisbie and McAllester 1992). As of 1982, there were over 1,000 Hataałii, or Singers otherwise known as 'Medicine People', qualified to perform one or more of thirty ceremonials and countless prayer rituals (Frisbie and Tso n.d.) which restore hozhó or harmonious condition, good health, serenity, and balance.

These songs are the most sacred holy songs, the "complex and comprehensive" spiritual literature of the Navajo, may be considered classical music (McAllester and Mitchell 1983), while all other songs, including personal, patriotic, daily work, recreation, jokes, and less sacred ceremonial songs, may be considered popular music. The "popular" side is characterized by public performance while the holy songs are preserved of their sacredness by reserving it only for ceremonies (and thus not featured on the recording listed at bottom). (ibid)

The longest ceremonies may last up to nine days and nights while performing rituals that restore the balance between good and evil, or positive and negative forces. The hataałii, aided by sandpaintings or masked yeibicheii, as well as numerous other sacred tools used for healing, chant the sacred songs to call upon the Navajo gods and natural forces to restore the person to harmony and balance within the context of the world forces. In ceremonies involving sandpaintings, the person to be supernaturally assisted, the patient, becomes the protagonist, identifying with the gods of the Diné Creation Stories, and at one point becomes part of the Story Cycle by sitting on a sandpainting with iconography pertaining to the specific story and deities. (McAllester 1981-1982)

The lyrics, which may last over an hour and are usually sung in groups, contain narrative epics including the beginning of the world, phenomenology, morality, and other lessons. Longer songs are divided into two or four balanced parts and feature an alternation of chantlike verses and buoyant melodically active choruses concluded by a refrain in the style and including lyrics of the chorus. Lyrics, songs, groups, and topics include cyclic: Changing Woman, an immortal figure in the Navajo traditions, is born in the spring, grows to adolescence in the summer, becomes an adult in the autumn, and then an old lady in the winter, repeating the life cycles over and over. Her sons, the Hero Twins, Monster Slayer and Born-for-the-Water, are also sung about, for they rid the world of giants and evil monsters. Stories such as these are spoken of during these sacred ceremonies.

The "popular" music resembles the highly active melodic motion of the choruses, featuring wide intervallic leaps and melodic range usually an octave to octave and a half. Structurally, the songs are created from the complex repetition, division, and combinations of most often no more than four or five phrases, with short songs often immediately following each other for continuity as needed in work songs. Their lyrics are mostly vocables, with certain vocables specific to genres, but may contain short humorous or satirical texts. (ibid)

Children's Songs

Navajo children's songs are usually about animals, such as pets and livestock. Some songs are about family members, and about chores, games, and other activities as well. It usually includes anything in a child's daily life. A child may learn songs from an early age from the mother. As a baby, if the child cries, the mother will sing to it while it's tied in the cradleboard. Navajo songs are rhythmic, and therefore soothing to a baby. Thus, songs are a major part of Navajo culture.

It may have been a kind of beginner's course in learning the songs and prayers for self-protection from bad things, most notably coyotes, skinwalkers, and other evil figures in Navajo traditions. Blessings, such as when one does with corn pollen in the early morning, may be learned as well.

In children's songs, a short chant usually starts off the song, followed by at least one stanza of lyrics, and finishing up with the same chant. All traditional songs include chants, and are not made up solely of lyrics. There are specific chants for some types of songs as well. Comtemporary children's songs, however, such as Christmas songs and Navajo versions of nursery rhymes, may have lyrics only. Today, both types of songs may be taught in elementary schools on the reservation, depending on the knowledge and ability of the particular teacher.

In earlier times, Navajo children may have sung songs like these to themselves while sheepherding, to pass the time. Sheep were, and still are, a part of Navajo life. Back then, giving a child custody of the entire herd was a way to teach them leadership and responsibility, for one day they would probably own a herd of their own. A child, idle while the sheep grazed, may sing to pass the time.

Peyote songs

Peyote songs are a form of Native American music, now most often performed as part of the Native American Church, which came to the northern part of the Navajo Nation around 1936. They are typically accompanied by a rattle and water drum, and are used in a ceremonial aspect during the sacramental taking of peyote. Peyote songs share characteristics of Apache music and Plains-Pueblo music. (Nettl 1956, p.114)

In recent years, a modernized version of peyote songs have been popularized by Verdell Primeaux, a Sioux, and Johnny Mike, a Navajo.

Contemporary popular

The Navajo music scene is perhaps one of the strongest in native music today. In the past, Navajo musicians were corraled into maintaining the status quo of traditional music, chants and/or flute compositions. Today, Navajo bands span the genres of punk, metal, hardcore, hip hop, blues, rock, death metal, stoner rock, country, and even traditional. Success of bands like Blackfire, Ethnic De Generation, Downplay, Mother Earth Blues Band, Tribal Live and other musicians have reignited an interest in music with the younger Navajo generations. Perhaps the best synthesis of tradition and contemporary is found in the musical marriage of Tribe II Entertainment, a rap duo from Arizona, Mistic, Rollin, Lil' Spade and Shade are truly right now, the only Native American rappers who can rap entirely in their native tongue. Their popularity and bilingual ability is yet another look at the prolific nature of the Navajo music scene.

Notes

- ↑ For example, the Great Canadian Parks website suggests that the Navajo may be descendants the lost Naha tribe, a Slavey tribe from the Nahanni region west of Great Slave Lake. Nahanni National Park Reserve. Great Canadian Parks. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ↑ Haile, Berard. "Soul Concepts of the Navajo." Annali Lateranense, Vol. VII. Citta del Vaticano, 1943

- ↑ McNeley, James K. Holy Wind in Navajo Philosophy. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1981.

- ↑ Robert S. McPherson, Sacred Land, Sacred View: Navajo perceptions of the Four Corners Region, Brigham Young University, ISBN 1-56085-008-6.

- ↑ Kluckhohn, p.27

Bibliography

- Bailey, L. R. (1964). The Long Walk: A History of the Navaho Wars, 1846–1868.

- Bighorse, Tiana. (1990). Bighorse the Warrior. Ed. Noel Bennett, Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Brown, Dee (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. ISBN 0-330-23219-3.

- Brugge, David M. (1968). Navajos in the Catholic Church Records of New Mexico 1694–1875. Window Rock, Arizona: Reseach Section, The Navajo Tribe.

- Clarke, Dwight L. (1961). Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press a

- Downs, James F. (1972). The Navajo. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Dyke, Walter (1967). Son of Old Man Hat. Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books & University of Nebraska Press. LCCN 44-2654.

- Forbes, Jack D. (1960). Apache, Navajo and Spaniard. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCN 60-13480.

- Gilpin, Laura. (1968). The Enduring Navaho. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Gold, Peter (1994). Navajo & Tibetan Sacred Wisdom: The Circle of the Spirit. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International. ISBN 0-89281-411-X. .

- Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito (editors) (1940). Narratives of the Coronado Expedition 1540–1542. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Henderson, Richard.(1994). “Replicating Dog Travois Travel on the Northern Plains.” Plains Anthropologist, V39:145–59

- Iverson, Peter. (2002). Diné: A History of the Navahos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2714-1

- Kelly, Lawrence (1970). Navajo Roundup, Pruett Pub. Co., Colorado.

- Kluckholm, Clyde & Leighton, Dorothea (1946). The Navaho. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

- Loewen, James. W. (1999). Lies Across America. Pages 100–101; The New Press.

- McNitt, Frank. (1972). Navajo Wars. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Newcomb, Franc Johnson (1964). Hosteen Klah: Navajo Medicine Man and Sand Painter. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCCN 64-20759.

- Plog, Stephen. Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest. Thames and London, LTD, London, England, 1997. ISBN 0-500-27939-X.

- Compiled (1973). Roessel, Ruth (editor). Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press.

- Compiled (1974). in Roessel, Ruth: Navajo Livestock Reduction: A National Disgrace. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. ISBN 0-912586-18-4.

- Terrell, J. U. (1970). The Navajos.

- Underhill, Ruth M. (1956). The Navahos. Norman: The University of Oklahoma Press.

- Witherspoon, Gary. (1977). Language and Art in the Navajo Universe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda.(1991) The Encyclopedia of Amazons. Paragon House. Page 255. ISBN 1-55778-420-5

- Zolbrod, Paul G. Diné bahané: The Navajo Creation Story. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

- Liner notes: Navajo Songs (1992), recorded by Laura Boulton in 1933 and 1940, annotated by Charlotte J. Frisbie and David McAllester. Smithsonian Folkways: SF 40403.

- Kluckhohn, Clyde. Navaho Witchcraft. Beacon Press, Boston, 1944. Library of Congress cat. No. 62-13533

- Wall, Leon and William Morgan. Navajo-English Dictionary. (Hippocrene Books, New York City, 1998 ISBN 0-7818-0247-4

- Young, Robert W. and William Morgan. Colloquial Navajo, a Dictionary. Hippocrene Books, New York City, 1998 ISBN 0-7818-0278-4

- Wall, Leon and William Morgan, Navajo-English Dictionary. (Hippocrene Books, New York City, 1998 ISBN 0-7818-0247-4)

- Brady, M.K., Some Kind of Power: Navaho Children's Skinwalker Narratives. (University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, 1984 ISBN 0-87480-238-5)

- Marika, K.. Werewolves, Shapeshifters and Skinwalkers. (Sherbourne Press, Los Angeles, 1972)

- Teller, J. The Navajo Skinwalker, Witchcraft, & Related Spiritual Phenomena: Spiritual Clues: Orientation to the Evolution of the Circle. Infinity Horn Publishing, Chinle AZ, 1997 ISBN 0-9656014-0-4)

- Kluckhohn, Clyde. Navaho Witchcraft. Beacon Press, Boston, 1944. Library of Congress cat. No. 62-13533

External links

- Middle Ground Project of Northern Colorado University with images of U.S. documents of treaties and reports 1846–1931

- Navajo People information by State of Utah

- A Brief Overview of the Navajo People (as of October 18, 2004)

- Navajo Silversmiths, by Washington Matthews, 1883 from Project Gutenberg

- Navajo Institute for Social Justice

- Navajo Jewelry Information

- Navajo Artcrafts Website created by students of GreyHills Academy High School in Tuba City AZ.

- Navajo weaving

- Historic Collection of Navajo Pictures

- Spanish-Navajo dictionary on line AULEX

- Navajo Tourism Website for the Navajo Tourism Department

- Non-Profit Navajo Arts & Crafts Enterprise

- Navajo Witches—Skinwalkers

- Skinwalkers

- Navajo Skinwalkers

- Rare carving of a Skin Walker

- American Werewolves in Folklore and Mythology

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Navajo_people history

- Navajo_mythology history

- Navajo_music history

- Witch_(Navajo) history

- Skin-walker history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.