Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance running event of 42.195 km (26 miles 385 yards) that can be run either as a road race or off-road (for example, on mountain trails).

History

Template:Cleanup The name, "marathon", comes from the legend of Pheidippides, a Greek soldier, who was sent from the town of Marathon to Athens to announce that the Persians had been miraculously defeated in the Battle of Marathon. It is said that he ran the entire distance without stopping, but moments after proclaiming his message to the city he collapsed dead from exhaustion. The account of the run from Marathon to Athens first appears in Plutarch's On the Glory of Athens in the 1st century AD who quotes from Heraclides Ponticus' lost work, giving the runner's name as either Thersipus of Erchius or Eucles.[1] Lucian of Samosata (2nd century AD) also gives the story but names the runner Philippides (not Pheidippides).[2]

The Greek historian Herodotus, the main source for the Greco-Persian Wars, mentions Pheidippides as the messenger who ran from Athens to Sparta asking for help. In some Herodotus manuscripts the name of the runner between Athens and Sparta is given as Philippides.

There are two roads out of the battlefield of Marathon towards Athens, one more mountainous towards the north whose distance is about 34.5 km (21.4 miles), and another flatter but longer towards the south with a distance of 40.8 km (25.4 miles). It has been argued that the ancient runner took the more difficult northern road because at the time of the battle there were still Persian soldiers in the south of the plain.

In 1876, Robert Browning wrote the poem "Pheidippides". Browning's poem, his composite story, became part of late 19th century popular culture and was accepted as an historic legend.

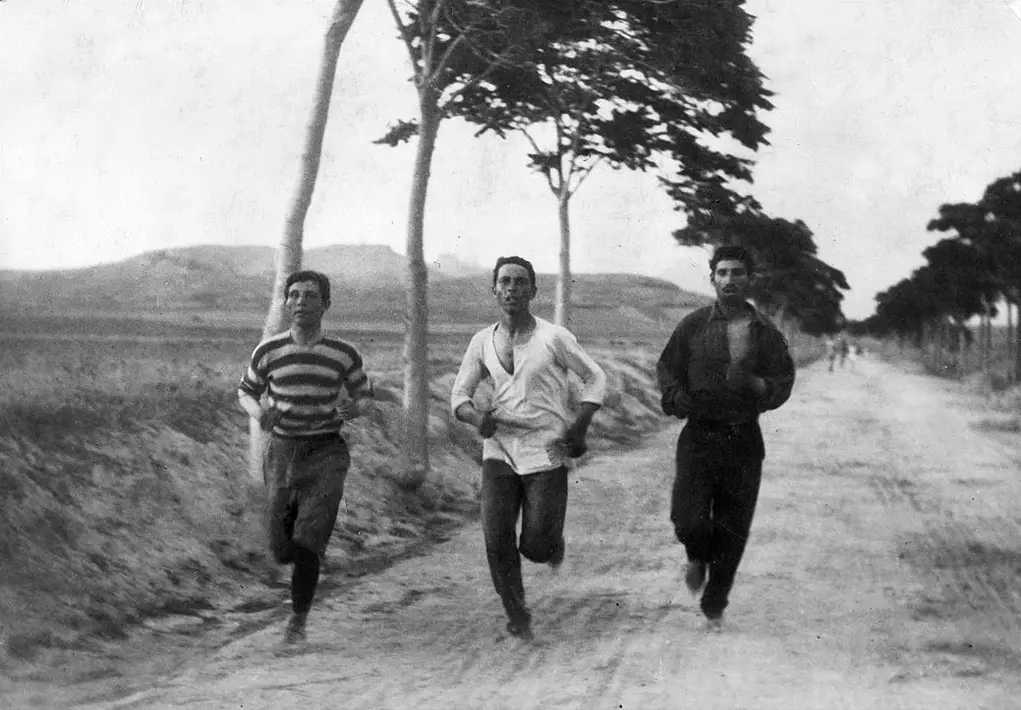

When the idea of a modern Olympics became a reality at the end of the 19th century, the initiators and organizers were looking for a great popularizing event, recalling the ancient glory of Greece. The idea of organizing a Marathon race came from Michel Bréal, who wanted the event to feature in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 in Athens. This idea was heavily supported by Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, as well as the Greeks. The Greeks staged a selection race for the Olympic marathon, and this first marathon was won by Charilaos Vasilakos in 3 hours and 18 minutes (with the future winner of the introductory Olympic Games marathon coming in fifth). The winner of the first Olympic Marathon in 1896 (a male only race) was Spiridon "Spiros" Louis, a Greek water-carrier. He won at the Olympics in 2 hours, 58 minutes and 50 seconds, despite stopping on the way for a glass of wine from his uncle waiting near the village of Chalandri.[citation needed]

The women's marathon was introduced at the 1984 Summer Olympics (Los Angeles, USA).

Distance

| Year | Distance (kilometres) |

Distance (miles) |

|---|---|---|

| 1896 | 40 | 24.85 |

| 1900 | 40.26 | 25.02 |

| 1904 | 40 | 24.85 |

| 1906 | 41.86 | 26.01 |

| 1908 | 42.195 | 26.22 |

| 1912 | 40.2 | 24.98 |

| 1920 | 42.75 | 26.56 |

| Since 1924 |

42.195 | 26.22 |

The length of a marathon was not fixed at first, since the only important factor was that all athletes competed on the same course. The marathon races in the first few Olympic Games were not of a set length, but were roughly fixed at around 24 miles, the distance from Marathon to Athens.[3] The exact length of the Olympic marathon varied depending on the route established for each venue.

The marathon at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London was set to measure about 25 miles and to start on ‘The Long Walk’ – a magnificent avenue leading up to Windsor Castle in the grounds of Windsor Great Park. The Princess of Wales wanted her children to watch the start of the race, so the start of the race was moved to the east lawn of Windsor Castle, increasing its length to 26 miles.[3] The race was to finish as the Great White City Stadium in Shepherd's Bush in London; however, Queen Alexandra insisted on having the best view of the finish; so, in the words of the official Olympic report, "385 yards were run on the cinder track to the finish, below the Royal Box".[3] The length then became 42.195 km (26 miles 385 yards).

For the next Olympics in 1912, the length was changed to 40.2 km (24.98 miles) and changed again to 42.75 km (26.56 miles) for the 1920 Olympics until it was fixed at the 1908 distance for the 1924 Olympics. In fact, of the first seven Olympic Games, there were six different marathon distances between 40 km and 42.75 km (40 km being used twice).

Following the 1908 Olympics in London, an annual event called the Polytechnic Marathon had been instituted over the 1908 distance of 26 miles 385 yards (42.195 km), and it was largely due to the prestige of the Polytechnic Marathon that 42.195 km was adopted as the official marathon distance in 1921 by the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) - Rule 240 of their Competition Rules.[1]. The distance converted into miles, 26.2187, has been rounded to 26.22 in the table (a difference of about two yards).

World records and “world's best”

World records were not officially recognised by the IAAF until 1 January 2004; previously, the best times for the Marathon were referred to as the 'world best'. Courses must conform to IAAF standards for a record to be recognized. However, marathon routes still vary greatly in elevation, course, and surface, making exact comparisons impossible. Typically, the fastest times are set over relatively flat courses near sea level, during good weather conditions and with the assistance of pacesetters.

The world record time for men over the distance is 2 hours 4 minutes and 55 seconds, set in the Berlin Marathon by Paul Tergat of Kenya on September 28, 2003 (ratified as the world record by the IAAF on 1 January 2004), an improvement of 20 minutes and 44 seconds since 1947 (Marathon world best progression). The world record for women was set by Paula Radcliffe of United Kingdom in the London Marathon on 13 April 2003, in 2 hours 15 minutes and 25 seconds. This time was set using male pacesetters — the fastest time by a woman without using a male pacesetter ('woman-only') was also set by Paula Radcliffe, again during the London Marathon, with a time of 2 hours 17 minutes and 42 seconds set on 17 April 2005.

All-time men's best marathon times under 2h 10'30"

All-time women's best marathon times under 2h 30'00"

Olympic traditions

Since the modern games were founded, it has become a tradition for the men's Olympic marathon to be the last event of the athletics calendar, with a finish inside the Olympic stadium, often within hours of, or even incorporated into, the closing ceremonies. The Marathon of the 2004 Summer Olympics revived the long-established route from Marathon to Athens ending at Panathinaiko Stadium, the venue for the 1896 Summer Olympics.

Running a marathon

General

Completing a marathon is considered very difficult, but many coaches believe that it is possible for anyone who is willing to put in the time and effort. Various first-person accounts of (first-time) marathon training and successful racing can be found on the internet, e.g. on the Dead Runners Society electronic mailing list.

Finish times for non-professional runners

Obviously, most participants do not run a marathon to win. More important for most runners is their personal finish time and their placement within their specific age group and gender. Another very important goal is to break certain time barriers. For example, ambitious recreational first-timers often try to run the marathon under 4 hours; more competitive runners may attempt to run under 3 hours.

Other benchmarks are the qualifying times for major marathons. Especially important among these are the times necessary to obtain entry for the Boston Marathon, the only marathon which requires qualifying times for all non-professional runners.

Training

For most runners, the marathon is the longest run they have ever attempted. Many coaches believe that the most important element in marathon training is the long run. Recreational runners commonly try to reach a maximum of about 20 miles (32 kilometres) in their longest weekly run and about 40 miles (64 kilometres) a week in total when training for the marathon, but wide variability exists in practice and in recommendations. More experienced marathoners may run a longer distance, and more miles or kilometres during the week. Greater weekly training mileages can offer greater results in terms of distance and endurance, but also carry a greater risk of training injury. Most male elite marathon runners will have weekly mileages of over 100 miles (160 kilometres).[4]

Many training programs last a minimum of five or six months, with a gradual increase (every two weeks) in the distance run and a little decrease (1 week) for recovery. For beginners looking to merely finish a marathon, a minimum of 4 months of running 4 days a week is recommended (Whitsett et al. 1998). Many trainers recommend a weekly increase in mileage of no more than 10%. It is also often advised to maintain a consistent running program for six weeks or so before beginning a marathon training program to allow the body to adapt to the new stresses.[5]

During marathon training, adequate recovery time is important. If fatigue or pain is felt, it is recommended to take a break for a couple of days or more to let the body heal. Overtraining is a condition that results from not getting enough rest to allow the body to recover from difficult training. It can actually result in a lower endurance and speed and place a runner at a greater risk of injury.[4]

Before the race

During the last two or three weeks before the marathon, runners will typically reduce their weekly training, gradually, by as much as 50%-75% of previous peak volume, and take at least a couple of days of complete rest to allow their bodies to recover from any strong effort. The last long training run might be undertaken no later than two weeks prior to the event. This is a phase of training known as tapering. Many marathoners also "carbo-load" (increase their carbohydrate intake while holding total caloric intake constant) during the week before the marathon to allow their bodies to store more glycogen.

Immediately before the race, many runners will refrain from eating solid food to avoid digestive problems. They will also ensure that they are fully hydrated beforehand. Light stretching before the race is believed by many to help keep muscles limber.

During the race

Coaches recommend trying to maintain as steady a pace as possible when running a marathon. Many novice runners make the mistake of trying to "bank time" early in the race by starting with a quicker pace than they can actually hope to maintain for the entire race. This strategy can backfire, leaving the runner without enough energy to complete the race or causing the runner to cramp. Therefore, some coaches advise novice runners to start out slower than their average goal pace to save energy for the second half of the race (negative splits). As an example, the first five to eight miles might be run at a pace 15-20 seconds per mile slower than the target pace for later miles.

Typically, there is a maximum allowed time of about six hours after which the marathon route is closed, although some larger marathons (such as Myrtle Beach, Marine Corps and Honolulu) keep the course open considerably longer (eight hours or more). Runners still on the course at that time are picked up by a truck and carried to the finish line. Finishing a marathon at all is a worthy accomplishment. Times under four hours (9:09 per mile) are considered a superior achievement for amateurs.

Water consumption dangers

Water and light sports drinks offered along the race course should be consumed regularly in order to avoid dehydration. While drinking fluids during the race is absolutely necessary for all runners, in some cases too much drinking can also be dangerous. Drinking more than one loses during a race can decrease the concentration of sodium in the blood (a condition called hyponatremia), which may result in vomiting, seizures, coma and even death.[6] Eating salt packets during a race possibly can help with this problem. The International Marathon Medical Directors Association issued a warning in 2001 that urged runners only to drink when they are thirsty, rather than "drinking ahead of their thirst."

An elite runner never has the time to drink too much water. However, a slower runner can easily drink too much water during the four or more hours of a race and immediately afterwards. Water overconsumption typically occurs when a runner is overly concerned about being dehydrated and overdoes the effort to drink enough. The amount of water required to cause complications from drinking too much may be only 3 liters, or even less, depending on the individual. Women are more prone to hyponatremia than men. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 13% of runners completing the 2002 Boston Marathon had hyponatremia.[7]

A 4+ hour runner can drink about 4-6 ounces (120-170 ml) of fluids every 20-30 minutes without fear of hyponatremia. It is not clear that consuming sports drinks or salty snacks reduces risk. A patient suffering hyponatremia can be given a small volume of a concentrated salt solution intravenously to raise sodium concentrations in blood. Since taking and testing a blood sample takes time, runners should weigh themselves before running and write the results on their bibs. If anything goes wrong, first aid workers can use the weight information to tell if the patient had consumed too much water.

Glycogen and “the wall”

Carbohydrates that a person eats are converted by the liver and muscles into glycogen for storage. Glycogen burns quickly to provide quick energy. Runners can store about 8 MJ or 2,000 kcal worth of glycogen in their bodies, enough for about 30 km or 18-20 miles of running. Many runners report that running becomes noticeably more difficult at that point.[citation needed] When glycogen runs low, the body must then burn stored fat for energy, which does not burn as readily. When this happens, the runner will experience dramatic fatigue. This phenomenon is called "hitting the wall". The aim of training for the marathon, according to many coaches,[citation needed] is to maximize the limited glycogen available so that the fatigue of the "wall" is not as dramatic. This is in part accomplished by utilizing a higher percentage of energy from burned fat even during the early phase of the race, thus conserving glycogen.

Carbohydrate-based "energy" gels such as PowerGel or Gu are a good way to avoid or reduce the effect of "hitting the wall" as they provide easy to digest energy during the run. Most experts recommend taking an energy gel every 45-60 minutes during the race. Energy gels usually contain varying amounts of sodium and potassium and some also contain caffeine. They need to be consumed with a certain amount of water.

After a marathon

It is normal to experience muscle soreness after a marathon. This is usually attributed to microscopic tears in the muscles. It causes a characteristic awkward walking style that is immediately recognizable by other runners. Muscle soreness usually abates within a week, but most runners will take about three weeks to completely recover to pre-race condition.

The immune system is reportedly suppressed for a short time. Studies have indicated that an increase in vitamin C in a runner's post-race diet decreases the chance of sinus infections, a relatively common condition, especially in ultramarathons. Changes to the blood chemistry may lead physicians to mistakenly diagnose heart malfunction.

It is still possible to overdrink water after the race has finished, and runners should take care not to overconsume water in the immediate hours after finishing the race.

Due to the stress on the body during a marathon, a person's kidneys can shut down, leading to the accumulation of toxins in the blood. This is especially dangerous if the runner has consumed any medications such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or acetaminophen (Tylenol). If a runner has not urinated within 4-6 hours after the marathon despite consuming adequate fluids, he or she should seek medical attention.

It is relatively common to only come to realize that there are injuries to the feet and knees after the marathon has finished. Blisters on the feet and toes commonly only become painful after the race is over. Some runners may experience toenails which turn black and sometimes subsequently detach from the toe. This is from the toenails being too long and impacting on the front of the shoe.

Some sports doctors advise that gentle exercise in the week after the marathon can aid muscle recovery, but obviously this must be tailored to the individual situations. Receiving a sports massage from a licensed massage therapist is a good idea within 24-48 hours after finishing a marathon. Massage has been shown to have less benefit if received immediately after the race.[citation needed]

Cardiac risks

A study published in 1996[8] found that the risk of having a fatal heart attack during, or in the period 24 hours after, a marathon, was approximately 1 in 50,000 over an athlete's racing career - which the authors characterised as an "extremely small" risk. The paper went on to say that since the risk was so small, cardiac screening programs for marathons were not warranted. However, this study was not an attempt to assess the overall benefit or risk to cardiac health of marathon running.

In 2006, a study of 60 non-elite marathon participants tested runners for certain proteins which indicate heart damage or dysfunction after they had completed the marathon, and gave them ultrasound scans before and after the race. The study revealed that, in that sample of 60 people, runners who had done less than 35 miles per week training before the race were most likely to show some heart damage or dysfunction, while runners who had done more than 45 miles per week training beforehand showed little or no heart problems.[9]

It should be emphasised that regular exercise in general provides a range of health benefits, including a substantially reduced risk of heart attacks. Moreover, these studies only relate to marathons, not to other forms of running. It has been suggested that as marathon running is a test of endurance, it stresses the heart more than shorter running activities, and this may be the reason for the reported findings.

Helpful devices

A variety of devices are available to assist runners with pacing, and to provide near real time data such as distance travelled, lap and total elapsed time, and calories burned. Popular manufacturers of such devices include Timex, Polar, and Garmin.

These devices typically employ one of two types of technologies: an integrated GPS (Global Positioning System) receiver, or an inertial footpod. GPS devices calculate pace and distance by periodically calculating the wearer's location relative to a network of satellites using a process known as multilateration. Inertial footpods employ a device which clips to the runner's shoe and wirelessly transmits pace data to a paired wristwatch. Inertial footpod technology has the advantages of being cheaper, and functional when there is no line of sight to a sufficient number of GPS satellites (due to tall buildings, trees, etc.)

A heart rate monitor is another helpful device. These typically comprise a transmitter (which is strapped around the runner's chest) and a paired wristwatch, which receives data from the transmitter and provides feedback to the runner. During a training session or race, the runner can view his or her heart rate in beats per minute, which can provide objective feedback about that session's level of running intensity.

Some devices combine pace/distance technology and heart rate monitoring technology into one unit.

Marathon races

More than 800 annual marathons are organized in most countries of the world. Many of these belong to the Association of International Marathons and Distance Races (AIMS) which has grown since its foundation in 1982 to embrace 238 member events in 82 countries and territories. Five of the largest and most prestigious races, Boston, New York City, Chicago, London, and Berlin, form the biannual World Marathon Majors series, awarding $500,000 annually to the best overall male and female performers in the series. Other notable large marathons include Washington, D.C./Virginia, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Rome and Paris. One of the more unusual marathons is the Midnight Sun Marathon held in Tromsø, Norway at 70 degrees North. Using unofficial and temporary courses, measured by GPS, races of marathon distance are now held at the North Pole, in Antarctica and over desert terrain. Among other unusual marathons can be mentioned: The Great Wall of China Marathon on The Great Wall of China, The Big Five Marathon among the safari wildlife of South Africa, The Great Tibetan Marathon - a marathon in an atmosphere of Tibetan Buddhism at an altitude of 3500 meters, and The Polar circle marathon on the permanent ice cap of Greenland in -15 degrees Celsius/+5 degrees Fahrenheit temperatures. The Intercontinental Istanbul Eurasia Marathon is the only marathon where participants run over two continents, Europe and Asia, during the course of a single event. The historic Polytechnic Marathon which gave the world the standard distance of 26.2 miles finally died out in 1996.

Marathon races usually use the starting format called mass start, though larger races may use a wave start, where different genders or abilities may begin at different times.

Notable marathon runners

This is a list of elite athletes notable for their performance in marathoning. For a list of people notable in other fields who have also run marathons, see list of marathoners.

Men

- Gezahegne Abera

- Abel Antón

- Stefano Baldini

- Dick Beardsley

- Abebe Bikila

- Amby Burfoot

- Bob Busquaert

- Dionicio Cerón

- Robert Cheruiyot

- Waldemar Cierpinski

- Derek Clayton

- Robert de Castella

- Martín Fiz

- Bruce Fordyce

- Haile Gebrselassie

- Hal Higdon

- Juma Ikangaa

- Steve Jones

- Bob Kempainen

- Khalid Khannouchi

- Hannes Kolehmainen

- Tom Longboat

- Carlos Lopes

- Spiridon Louis

- Gerard Nijboer

- Jim Peters

- Julio Rey

- Bill Rodgers

- Evans Rutto

- Alberto Salazar

- Toshihiko Seko

- Frank Shorter

- German Silva

- Albin Stenroos

- Paul Tergat

- Ed Whitlock

- Geri Winkler

- Mamo Wolde

- Emil Zátopek

Women

- Elfenesh Alemu

- Carla Beurskens

- Katrin Dörre-Heinig

- Lidiya Grigoryeva

- Helena Javornik

- Deena Kastor

- Lornah Kiplagat

- Renata Kokowska

- Ingrid Kristiansen

- Catherina McKiernan

- Rosa Mota

- Catherine Ndereba

- Mizuki Noguchi

- Uta Pippig

- Paula Radcliffe

- Fatuma Roba

- Joan Benoit Samuelson

- Naoko Takahashi

- Grete Waitz

- Getenesh Wami

World all times list (men)

| Time | Athlete | Country | Date | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2h04:55 | Paul Tergat | Kenya | 28 September 2003 | Berlin |

| 2h04:56 | Sammy Korir | Kenya | 28 September 2003 | Berlin |

| 2h05:38 | Khalid Khannouchi | United States | 14 April 2002 | London |

| 2h05:50 | Evans Rutto | Kenya | 12 October 2003 | Chicago |

| 2h05:56 | Haile Gebrselassie | Ethiopia | 24 September 2006 | Berlin |

| 2h06:05 | Ronaldo da Costa | Brazil | 20 September 1998 | Berlin |

| 2h06:14 | Felix Limo | Kenya | 4 April 2004 | Rotterdam |

| 2h06:15 | Titus Munji | Kenya | 28 September 2003 | Berlin |

| 2h06:16 | Moses Tanui | Kenya | 24 October 1999 | Chicago |

| 2h06:16 | Daniel Njenga | Kenya | 13 October 2002 | Chicago |

| 2h06:16 | Toshinari Takaoka | Japan | 13 October 2002 | Chicago |

World all times list (women)

| Time | Athlete | Country | Date | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2h15:25 | Paula Radcliffe | United Kingdom | 13 April 2003 | London |

| 2h18:47 | Catherine Ndereba | Kenya | 7 October 2001 | Chicago |

| 2h19:12 | Mizuki Noguchi | Japan | 25 September 2005 | Berlin |

| 2h19:36 | Deena Kastor | United States | 23 April 2006 | London |

| 2h19:39 | Sun Yingjie | China | 19 October 2003 | Beijing |

| 2h19:41 | Yoko Shibui | Japan | 26 September 2004 | Berlin |

| 2h19:46 | Naoko Takahashi | Japan | 30 September 2001 | Berlín |

| 2h19:51 | Zhou Chunxiu | China | 12 March 2006 | Seoul |

| 2h20:42 | Berhane Adere | Ethiopia | 22 October 2006 | Chicago |

See also

- The Flying Finns

- Half marathon

- List of half marathon races

- List of marathon races

- Man versus Horse Marathon

- Mountain Marathon

- Mount Marathon Race

- Multiday race

- Running

- Pheidippides

- Ski Marathon

- Ultramarathon

- Ironman Triathlon

- Rosie Ruiz

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Moralia 347C

- ↑ A slip of the tongue in Salutation, Chapter 3

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 J.Bryant, 100 Years and Still Running, Marathon News (2007)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Daniels, J. PhD (2005). Daniels' Running Formula, 2nd Ed.. Human Kinetics Publishing. ISBN 0-7360-5492-8.

- ↑ Burfoot, A. Ed (1999). Runner's World Complete Book of Running : Everything You Need to Know to Run for Fun, Fitness and Competition. Rodale Books. ISBN 1-57954-186-0.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4927936.stm Water danger for marathon runners

- ↑ Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon

- ↑ http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(96)00137-4

- ↑ http://bankingmiles.blogspot.com/2006/11/marathons-dangerous-for-your-heart.html

- Whitsett, et al (1998). The Non-Runner's Marathon Trainer. Master's Press.

- Hyponatremia among Runners in the Boston Marathon by Christopher S.D. Almond, M.D., M.P.H., Andrew Y. Shin, M.D., Elizabeth B. Fortescue, M.D., Rebekah C. Mannix, M.D., David Wypij, Ph.D., Bryce A. Binstadt, M.D., Ph.D., Christine N. Duncan, M.D., David P. Olson, M.D., Ph.D., Ann E. Salerno, M.D., Jane W. Newburger, M.D., M.P.H., and David S. Greenes, M.D.

- American Family Physician: Sudden death in young athletes: screening for the needle in a haystack among other statistics, this reference link mentions the estimate that there is approximately 1 fatality per every 50000 people finishing a marathon.

External links

| Athletics events | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Sprints: 60 m | 100 m | 200 m | 400 m Hurdles: 60 m hurdles | 100 m hurdles | 110 m hurdles | 400 m hurdles Middle distance: 800 m | 1500 m | 3000 m | steeplechase Long distance: 5,000 m | 10,000 m | half marathon | marathon | ultramarathon | multiday races | Cross country running Relays: 4 × 100 m | 4 × 400 m; Racewalking; Wheelchair racing Throws: Discus | Hammer | Javelin | Shot put Jumps: High jump | Long jump | Pole vault | Triple jump Combination: Pentathlon | Heptathlon | Decathlon Highly uncommon: Standing high jump | Standing long jump | Standing triple jump | ||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.