Difference between revisions of "Manticore" - New World Encyclopedia

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Mythical creatures]] | ||

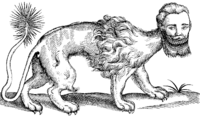

| + | [[Image:ManticoraTHoFFB1607.png|thumb|200 px|Manticore illustration from ''The History of Four-footed Beasts'' (1607), by [[Edward Topsell]].]] | ||

| − | + | The '''manticore''' is a [[legendary creature]] of Central [[Asia]], a kind of [[chimera (mythology)|chimera]], that is sometimes said to be related to the [[Sphinx]]. It was often feared as being violent and feral, but it was not until the manticore was incorporated into [[Europe]]an [[mythology]] during the [[Middle Ages]] that it came to be regarded as an [[omen]] of [[evil]]. | |

| − | + | Like many such beasts, there is dispute about the existence of the manticore. It has been suggested that tales of [[tiger]]s were embellished to create the even more fearsome manticore. Others maintained that such a [[species]] exists even today. At least, it exists in the world of [[fantasy]], providing a worthy and intriguing opponent for [[hero]]es. | |

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| − | Originally, the term manticore came into the [[English language]] from the [[ | + | Originally, the term ''manticore'' came into the [[English language]] from the [[Latin]] ''mantichora'', which was borrowed from the [[Greek language|Greek]] ''mantikhoras''. The Greek version of the word is actually an erroneous pronunciation of ''martikhoras'' from the original [[Persian language|early Middle Persian]] ''martyaxwar'', which translates as "man-eater" (''martya'' being "man" and ''xwar-'' "to eat").<ref> ''Oxford English Dictionary''.Oxford Press, 1971. ISBN 019861117X</ref> |

| − | ''martyaxwar'', which translates as "man-eater" (''martya'' being "man" and ''xwar-'' "to eat").<ref> | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | [[Image:Mantikor.jpg|thumb]] | + | [[Image:Mantikor.jpg|thumb|200 px|]] |

| − | Although versions | + | Although versions occasionally differ, the generalities of the manticore's description seem to be that it has the [[head (anatomy)|head]] of a [[man]] often with [[horn (anatomy)|horn]]s, gray or blue eyes, three rows of iron [[shark]]-like teeth, and a loud, trumpet/pipe-like roar. The body is usually of a (sometimes red-furred) [[lion]], and the [[tail]] of a [[dragon]] or [[scorpion]], which some believe can shoot out [[venom]]ous spines or hairs to incapacitate prey.<ref> [http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast177.htm "Manticore"] ''Medieval Bestiary'', 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2007. </ref> |

| − | The manticore is said to be able to leap in high and far bounds | + | The manticore is said to be able to shoot its spines either in front or behind, curving its tail over its body to shoot forwards, or straightening it tail to shoot them backwards. The only creature reputed to survive the poisonous stings is the [[elephant]]. Thus, hunters rode elephants when hunting the manticore.<ref> Nigg, Joe. ''The Book of Dragons & Other Mythical Beasts'', 2001.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | The manticore is said to be able to leap in high and far bounds; it is an excellent hunter, and is said to have a special appetite for human flesh. Occasionally, a manticore will possess [[wing]]s of some description. | ||

==Origin== | ==Origin== | ||

| − | The manticore originated in [[Ancient Persia]] mythology and was brought to the Western mythology by [[Ctesias]], a Greek physician at the Persian court, in the fifth century B.C.E.<ref> | + | The manticore originated in [[Ancient Persia]]n [[mythology]] and was brought to the Western mythology by [[Ctesias]], a Greek physician at the Persian court, in the fifth century B.C.E..E.<ref>[http://www.monstrous.com/monsters/manticore.htm "Manticore"] ''Monstrous'', 1998. Retrieved September 20, 2007. </ref> The [[Roman Empire|Romanized]] Greek [[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]], in his ''Description of Greece'', recalled strange [[animal]]s he had seen at Rome and commented, |

| − | + | <blockquote>The beast described by Ctesias in his Indian history, which he says is called ''martichoras'' by the Indians and "man-eater" by the Greeks, I am inclined to think is the [[lion]]. But that it has three rows of [[tooth|teeth]] along each [[jaw]] and spikes at the tip of its tail with which it defends itself at close quarters, while it hurls them like an [[Archery|archer]]'s [[arrow]]s at more distant enemies; all this is, I think, a false story that the Indians pass on from one to another owing to their excessive dread of the beast. (''Description'', xxi, 5)</blockquote> | |

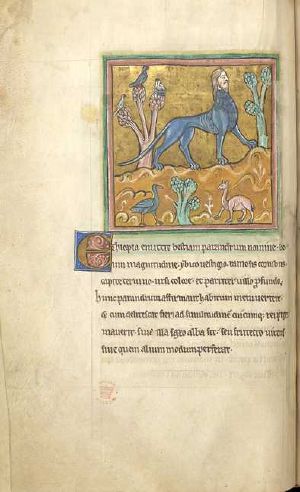

| + | [[Image:RochesterBestiaryFolio024vManticora.jpg|thumb|left|Folio 24v from a thirteenth century bestiary, ''The Rochester Bestiary'' (British Library, Royal MS 12 F XIII), showing the Manticora.]] | ||

| + | [[Pliny the Elder]] did not share Pausanias' [[skepticism]]. He followed [[Aristotle]]'s natural history by including the ''martichoras''—mis-transcribed as ''manticorus'' and thus passing into European languages—among his descriptions of animals in ''[[Naturalis Historia]]'', c. 77 C.E. Pliny's book was widely enjoyed and uncritically believed through the European [[Middle Ages]], during which the manticore was often illustrated in [[bestiary|bestiaries]]. | ||

| − | + | An Eastern version of the manticore is said by some locals to inhabit the jungles of [[Southeast Asia]], stalking villagers at night. While it is speculative if the locals actually believe in the [[mythical creature]]'s existence, or are merely carrying on a tradition is not clear. Outside of [[fantasy]] sub-culture, Southeast Asia is the only area in the world where accounts of manticores continue to be discussed. | |

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Tigerramki.jpg|right|thumb|220px|<div style="text-align: center;border:none">A wild Bengal tiger</div>]] |

| + | Some have considered the manticore to be no more than a [[tiger]], either a [[Bengal tiger]] or a [[Caspian tiger]], its fur appearing red in the sun. While those who saw such beasts, who have been known to attack and even eat humans (and were used in [[Roman empire|Roman]] arenas to fight gladiators), would naturally describe them as fearsome, for those who had never seen them all their characteristics would sound fantastic. Thus the three rows of teeth and the spines on the tail could well have become embellishments on tales of the tiger. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Heraldry== |

| − | The manticore made a late appearance in [[heraldry]], during the | + | The manticore made a late appearance in [[heraldry]], during the sixteenth century, influencing some [[Mannerism|Mannerist]] representations, such as [[Bronzino]]'s allegory ''The Exposure of Luxury,'' (National Gallery, London)<ref>Moffitt, John F. "An Exemplary Humanist Hybrid: Vasari's "Fraude" with Reference to Bronzino's 'Sphinx'." ''Renaissance Quarterly'' 49, No. 2, 1996: 303-333.</ref>—but more often in the decorative schemes called "[[Grotesque|grotteschi]]"—of the [[sin]] of [[Fraud]], conceived as a monstrous chimera with a [[beauty|beautiful]] [[woman]]'s face. In this way it passed by means of [[Cesare Ripa]]'s ''Iconologia'' into the seventeenth and eighteenth century [[France|French]] conception of a [[sphinx]]. It never was as popular as other mythological creatures used in heraldry, most likely because it always maintained an element of malevolance. |

| − | + | ==Symbolism== | |

| + | During the [[Middle Ages]], the manticore was sometimes seen as a [[symbol]] of the [[prophet]] [[Jeremiah]], since both were underground dwellers. However, positive connotations did not stick to the manticore. Its ferocious manner and terrifying appearance quickly made it a symbol of [[evil]], and the manticore in Europe came to be known as an [[omen]] of evil tidings. To see a manticore was to see a forthcoming calamity. Thus it came to imply bad luck, such as the proverbial black cat in modern society. | ||

==Pop Culture== | ==Pop Culture== | ||

| − | While not quite as popular as some other mythical | + | While not quite as popular as some other [[mythical creature]]s, the manticore has none the less been kept alive in the area [[fantasy]] sub-culture of modern society. |

| − | The manticore has made appearances in several fantasy novels, | + | The manticore has made appearances in several fantasy novels, including [[J.K. Rowling]]'s ''[[Harry Potter]]'' series. A manticore also featured as one of the unique creatures captured by the witch for her menagerie in [[Peter S. Beagle]]'s ''The Last Unicorn'', which was made into a popular [[animation|animated]] [[movie]]. The manticore also features in [[Robertson Davies]]' second novel of ''The Deptford Trilogy'', ''The Manticore'' (1972). |

| − | + | However, manticores' most prominent appearances are in role-playing and video games. ''Dungeons and Dragons'', ''Magic: The Gathering'', and the ''Warhammer Fantasy Battles'' all incorporate manticores. | |

| − | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Ashman, Malcolm and Joyce Hargreaves. ''Fabulous Beasts''. Overlook, 1997. ISBN 978-0879517793 | ||

| + | * Barber, Richard. ''Bestiary: Being an English Version of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Bodley 764''. Boydell Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0851157535 | ||

| + | * Borges, Jorge Luis. ''The Book of Imaginary Beings''. Amazon Remainders, 2005. ISBN 0670891800 | ||

| + | * Hassig, Debra. ''The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature''. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 041592894X | ||

| + | * Nigg, Joe. ''Wonder Beasts: Tales and Lore of the Phoenix, the Griffin, the Unicorn, and the Dragon''. Libraries Unlimited, 1995. ISBN 156308242X | ||

| + | * Nigg, Joe. ''The Book of Fabulous Beasts: A Treasury of Writings from Ancient Times to the Present''. Oxford University Press, USA, 1999. ISBN 978-0195095616 | ||

| + | * Nigg, Joe. ''The Book of Dragons & Other Mythical Beasts''. Barron's Educational Series, 2001. ISBN 978-0764155109 | ||

{{Credits|Manticore|115798589|}} | {{Credits|Manticore|115798589|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:37, 10 May 2009

The manticore is a legendary creature of Central Asia, a kind of chimera, that is sometimes said to be related to the Sphinx. It was often feared as being violent and feral, but it was not until the manticore was incorporated into European mythology during the Middle Ages that it came to be regarded as an omen of evil.

Like many such beasts, there is dispute about the existence of the manticore. It has been suggested that tales of tigers were embellished to create the even more fearsome manticore. Others maintained that such a species exists even today. At least, it exists in the world of fantasy, providing a worthy and intriguing opponent for heroes.

Etymology

Originally, the term manticore came into the English language from the Latin mantichora, which was borrowed from the Greek mantikhoras. The Greek version of the word is actually an erroneous pronunciation of martikhoras from the original early Middle Persian martyaxwar, which translates as "man-eater" (martya being "man" and xwar- "to eat").[1]

Description

Although versions occasionally differ, the generalities of the manticore's description seem to be that it has the head of a man often with horns, gray or blue eyes, three rows of iron shark-like teeth, and a loud, trumpet/pipe-like roar. The body is usually of a (sometimes red-furred) lion, and the tail of a dragon or scorpion, which some believe can shoot out venomous spines or hairs to incapacitate prey.[2]

The manticore is said to be able to shoot its spines either in front or behind, curving its tail over its body to shoot forwards, or straightening it tail to shoot them backwards. The only creature reputed to survive the poisonous stings is the elephant. Thus, hunters rode elephants when hunting the manticore.[3]

The manticore is said to be able to leap in high and far bounds; it is an excellent hunter, and is said to have a special appetite for human flesh. Occasionally, a manticore will possess wings of some description.

Origin

The manticore originated in Ancient Persian mythology and was brought to the Western mythology by Ctesias, a Greek physician at the Persian court, in the fifth century B.C.E.[4] The Romanized Greek Pausanias, in his Description of Greece, recalled strange animals he had seen at Rome and commented,

The beast described by Ctesias in his Indian history, which he says is called martichoras by the Indians and "man-eater" by the Greeks, I am inclined to think is the lion. But that it has three rows of teeth along each jaw and spikes at the tip of its tail with which it defends itself at close quarters, while it hurls them like an archer's arrows at more distant enemies; all this is, I think, a false story that the Indians pass on from one to another owing to their excessive dread of the beast. (Description, xxi, 5)

Pliny the Elder did not share Pausanias' skepticism. He followed Aristotle's natural history by including the martichoras—mis-transcribed as manticorus and thus passing into European languages—among his descriptions of animals in Naturalis Historia, c. 77 C.E. Pliny's book was widely enjoyed and uncritically believed through the European Middle Ages, during which the manticore was often illustrated in bestiaries.

An Eastern version of the manticore is said by some locals to inhabit the jungles of Southeast Asia, stalking villagers at night. While it is speculative if the locals actually believe in the mythical creature's existence, or are merely carrying on a tradition is not clear. Outside of fantasy sub-culture, Southeast Asia is the only area in the world where accounts of manticores continue to be discussed.

Some have considered the manticore to be no more than a tiger, either a Bengal tiger or a Caspian tiger, its fur appearing red in the sun. While those who saw such beasts, who have been known to attack and even eat humans (and were used in Roman arenas to fight gladiators), would naturally describe them as fearsome, for those who had never seen them all their characteristics would sound fantastic. Thus the three rows of teeth and the spines on the tail could well have become embellishments on tales of the tiger.

Heraldry

The manticore made a late appearance in heraldry, during the sixteenth century, influencing some Mannerist representations, such as Bronzino's allegory The Exposure of Luxury, (National Gallery, London)[5]—but more often in the decorative schemes called "grotteschi"—of the sin of Fraud, conceived as a monstrous chimera with a beautiful woman's face. In this way it passed by means of Cesare Ripa's Iconologia into the seventeenth and eighteenth century French conception of a sphinx. It never was as popular as other mythological creatures used in heraldry, most likely because it always maintained an element of malevolance.

Symbolism

During the Middle Ages, the manticore was sometimes seen as a symbol of the prophet Jeremiah, since both were underground dwellers. However, positive connotations did not stick to the manticore. Its ferocious manner and terrifying appearance quickly made it a symbol of evil, and the manticore in Europe came to be known as an omen of evil tidings. To see a manticore was to see a forthcoming calamity. Thus it came to imply bad luck, such as the proverbial black cat in modern society.

Pop Culture

While not quite as popular as some other mythical creatures, the manticore has none the less been kept alive in the area fantasy sub-culture of modern society. The manticore has made appearances in several fantasy novels, including J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. A manticore also featured as one of the unique creatures captured by the witch for her menagerie in Peter S. Beagle's The Last Unicorn, which was made into a popular animated movie. The manticore also features in Robertson Davies' second novel of The Deptford Trilogy, The Manticore (1972).

However, manticores' most prominent appearances are in role-playing and video games. Dungeons and Dragons, Magic: The Gathering, and the Warhammer Fantasy Battles all incorporate manticores.

Notes

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary.Oxford Press, 1971. ISBN 019861117X

- ↑ "Manticore" Medieval Bestiary, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ↑ Nigg, Joe. The Book of Dragons & Other Mythical Beasts, 2001.

- ↑ "Manticore" Monstrous, 1998. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ↑ Moffitt, John F. "An Exemplary Humanist Hybrid: Vasari's "Fraude" with Reference to Bronzino's 'Sphinx'." Renaissance Quarterly 49, No. 2, 1996: 303-333.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ashman, Malcolm and Joyce Hargreaves. Fabulous Beasts. Overlook, 1997. ISBN 978-0879517793

- Barber, Richard. Bestiary: Being an English Version of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Bodley 764. Boydell Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0851157535

- Borges, Jorge Luis. The Book of Imaginary Beings. Amazon Remainders, 2005. ISBN 0670891800

- Hassig, Debra. The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 041592894X

- Nigg, Joe. Wonder Beasts: Tales and Lore of the Phoenix, the Griffin, the Unicorn, and the Dragon. Libraries Unlimited, 1995. ISBN 156308242X

- Nigg, Joe. The Book of Fabulous Beasts: A Treasury of Writings from Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, USA, 1999. ISBN 978-0195095616

- Nigg, Joe. The Book of Dragons & Other Mythical Beasts. Barron's Educational Series, 2001. ISBN 978-0764155109

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.