Ma'at

| Goddess Ma'at[1] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|

Ma'at, reconstructed to have been pronounced as *Muʔʕat (Muh-aht),[2] was the Ancient Egyptian concept of law, morality, and justice[3] which was deified as a goddess.[4] Ma'at was seen as being charged with regulating the stars, seasons, and the actions of both mortals and gods.[5] As a goddess, her masculine counterpart was Thoth and their attributes go hand in hand.[6] Like Thoth,[7] she was seen to represent the Logos of Plato.[8] Her primary role in Egyptian mythology dealt with the weighing of words that took place in the underworld, Duat.[9]

Ma'at in an Egyptian Context

As an Egyptian deity, Ma'at belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.[10] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[11] The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[12] Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[13] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[14] Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[15]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the Hebrews, Mesopotamians and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[16] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[17] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead and of the gods place within it.

While Ma'at can be discussed as both a goddess and as an impersonal principle, it must be noted that this distinction was not made in her original religious context. Thus, the understanding of cosmic order always implied the theology (and concomitant ritualisms) centered on the goddess, just as the goddess was, herself, seen as the personification of this self-same order. Attempting to separate the two does an injustice to the cohesiveness and concreteness of the Egyptian religio-philosophical milieu. This being said, such a distinction is still the most efficient means of discursively exploring the goddess/principle, so long as the artificiality of such a distinction is acknowledged.

Ma'at as a principle

As a principle, "Ma'at" designated the fundamentally meaningful and orderly nature of the human and cosmic realms. Thus, the single term would be used in both contexts: cosmically, to describe both the cyclical transformation of seasons and the seasonal flooding of the Nile, and humanistically, to describe the orderly operation of human society and the moral code of its citizens. The conflation of these two realms signifies the extent to which human social codes were seen to be analogies of cosmic cycles, which essentially means that they were seen as both ontologically real and objectively true.[18] Thus, "to the Egyptian mind, Ma'at bound all things together in an indestructible unity: the universe, the natural world, the state and the individual were all seen as parts of the wider order generated by Ma'at."[19] The connotative richness of the concept of ma'at is attested to by Frankfort, who suggests:

- We lack words for conceptions which, like Maat, have ethical as well as metaphysical implications. We must sometimes translate "order," sometimes "truth," sometimes "justice"; and the opposites of Maat requires a similar variety of renderings. ... The laws of nature, the laws of society, and the divine commands all belong to the one category of what is right. The creator put order (or truth) in the place of disorder (or falsehood). The creator's successor, Pharaoh, repeated this significant act at his succession, in every victory, at the renovation of a temple, and so on.[20]

Given the immanence of ma'at in all aspects of the cosmos, Egyptian creation accounts often suggest that the principle of order was either the first element brought into existence or, more strikingly, that ma'at was, in fact, eternal (thus predating the existence of the world):[21] "she is the order imposed upon the cosmos created by the solar demiurge and as such is the guiding principle who accompanied the sun god at all times."[22] After the initial act of creation, the principle of order was understood to be immanently present in all natural and social systems—a notion that essentially ruled out the possibility of development or progress, as the original created state of the universe came to be seen as its moral apex.[23] Further, the universality of the principle meant that it applied equally to mortals and divinities: "all gods functioned within the established order; they all 'lived by Maat' and consequently they all hated 'untruth.' We may say that in Egyptian thought Maat, the divine order, mediated between man and gods."[24]

The human understanding of ma'at, which was soon codified into Egyptian law, was partially recorded in the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Later, these same concepts would be discussed by scholars and philosophers in their culture's Wisdom Literature (seboyet).[25] While many of these texts seem on the surface to be mundane guides to etiquette (as pertaining to various social or professional situations), even these banal human interactions were understood in light of ma'at. In this way, the most basic human behaviors came to possess a cosmic significance. However, instead of transforming the system into a rigid and punitive standard of behavior, this perspective actually humanized moral discourse:

- When man erred, he did not commit, in the first place, a crime against a god; he moved against the established order, and one god or another saw to it that that order was vindicated. ... By the same token the theme of God's wrath is practically unknown in Egyptian literature; for the Egyptian, in his aberrations, is not a sinner whom God rejects but an ignorant man who is disciplined and corrected.[26]

Ma'at as a goddess

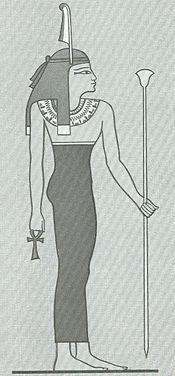

The goddess Ma'at is the personification of physical and moral law, order, and truth[27] represented as a woman, sitting or standing, holding a sceptre in one hand and an ankh in the other. Sometimes she is depicted with wings on each arm or a woman with an ostrich feather for a head.[28]

Because it was the pharaoh's duty to ensure truth and justice, many of them were referred to as Meri-Ma'at (Beloved of Ma'at). Since she was considered as merely the concept of order and truth, it was thought that she came into existence at the moment of creation, having no creator. When beliefs about Thoth arose and started to consume the earlier beliefs at Hermopolis about the Ogdoad, it was said that she was the mother of the Ogdoad and Thoth the father.

In Duat, the Egyptian underworld, the hearts of the dead were said to be weighed against the single Shu feather, symbolically representing the concept of Ma'at, in the Hall of Two Truths. A heart which was unworthy was devoured by Ammit and its owner condemned to remain in Duat. Those people with good, (and pure), hearts were sent on to Osiris in Aaru. The weighing of the heart, pictured on papyrus, (in the Book of the Dead, typically, or in tomb scenes, etc.), shows Anubis overseeing the weighing, the "lion-like" Ammit seated awaiting the results and the eating of the heart, the vertical heart on one flat surface of the balance scale, and the vertical Shu-feather standing on the other balance scale surface. Other traditions hold that Anubis brought the soul before the posthumous Osiris who performed the actual weighing.

Ma'at was commonly depicted in art as a woman with outstretched wings and a "curved" ostrich feather on her head or sometimes just as a feather. These images are on some sarcophagi as a symbol of protection for the souls of the dead. Egyptians believed that without Ma'at there would be only the primal chaos, ending the world. It was seen as the Pharaoh's necessity to apply just law.

Ma'at in Egyptian Religion

- judgment (should be intro'd above) - kingly offerings... no explicit temples

One aspect of ancient Egyptian funerary literature which is often mistaken for a codified ethic of ma'at is Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, often called the 42 Declarations of Purity or the Negative Confession. These declarations actually varied somewhat from tomb to tomb, and so can not be considered a canonical definition of ma'at. They appear rather to express each tomb owner's individual conception of ma'at, as well as working as a magical absolution (misdeeds or mistakes made by the tomb owner in life could be declared as not having been done, and through the power of the written word wipe that particular misdeed from his or her afterlife record). Many of the lines are similar, however, and they can help to give the student a "flavor" for the sorts of things which ma'at governed (which was basically everything- from the most formal to the most mundane aspect of life). Many versions are given online, unfortunately seldom do they ever note the tomb from which they came or whether they are a collection from various different tombs. Generally, they are each addressed to a specific deity, described in his or her most fearsome aspect. Ahmed Osman might believe the Book of the Dead preceded the Ten Commandments.[citation needed]

<this selection unifies the two domains (Maat as divine judge and Maat as objective standard)

Ma'at in the Egyptian Book of the Dead

- (1) "Hail, thou whose strides are long, who comest forth from Annu, I have not done iniquity.

- (2) "Hail, thou who art embraced by flame, who comest forth from Kheraba, I have not robbed with violence."

- (3) "Hail, Fentiu, who comest forth from Khemennu, I have not stolen."

- (4) "Hail, Devourer of the Shade, who comest forth from Qernet, I have done no murder; I have done no harm."

- (5) "Hail, Nehau, who comest forth from Re-stau, I have not defrauded offerings."

- (6) "Hail, god in the form of two lions, who comest forth from heaven, I have not minished oblations."

- (7) "Hail, thou whose eyes are of fire, who comest forth from Saut, I have not plundered the god."

- (8) "Hail, thou Flame, which comest and goest, I have spoken no lies."

- (9) "Hail, Crusher of bones, who comest forth from Suten-henen, I have not snatched away food."

- (10) "Hail, thou who shootest forth the Flame, who comest forth from Het-Ptah-ka, I have not caused pain."

- (11) "Hall, Qerer, who comest forth from Amentet, I have not committed fornication."

- (12) "Hail, thou whose face is turned back, who comest forth from thy hiding place, I have not caused shedding of tears."

- (13) "Hail, Bast, who comest forth from the secret place, I have not dealt deceitfully."

- (14) "Hail, thou whose legs are of fire, who comest forth out of the darkness, I have not transgressed."

- (15) "Hail, Devourer of Blood, who comest forth from the block of slaughter, I have not acted guilefully."

- (16) "Hail, Devourer of the inward parts, who comest forth from Mabet, I have not laid waste the ploughed land."

- (17) "Hail, Lord of Right and Truth, who comest forth from the city of Right and Truth, I have not been an eavesdropper."

- (18) "Hail, thou who dost stride backwards, who comest forth from the city of Bast, I have not set my lips in motion [against any man]."

- (19) "Hail, Sertiu, who comest forth from Annu, I have not been angry and wrathful except for a just cause."

- (20) "Hail, thou. being of two-fold wickedness, who comest forth from Ati (?) I have not defiled the wife of any man."

- (21) "Hail, thou two-headed serpent, who comest forth from the torture-chamber, I have not defiled the wife of any man."

- (22) "Hail, thou who dost regard what is brought unto thee, who comest forth from Pa-Amsu, I have not polluted myself."

- (23) "Hail, thou Chief of the mighty, who comest forth from Amentet, I have not caused terror."

- (24) "Hail, thou Destroyer, who comest forth from Kesiu, I have not transgressed."

- (25) "Hail, thou who orderest speech, who comest forth from Urit, I have not burned with rage."

- (26) "Hail, thou Babe, who comest forth from Uab, I have not stopped my ears against the words of Right and Truth."

- (27) "Hail, Kenemti, who comest forth from Kenemet, I have not worked grief"

- (28) "Hail, thou who bringest thy offering, I have not acted with insolence."

- (29) "Hail, thou who orderest speech, who comest forth from Unaset, I have not stirred up strife."

- (30) "Hail, Lord of faces, who comest forth from Netchfet, I have not judged hastily."

- (31) "Hail, Sekheriu, who comest forth from Utten, I have not been an eavesdropper."

- (32) "Hail, Lord of the two horns, who comest forth from Saïs, I have not multiplied words exceedingly."

- (33) "Hail, Nefer-Tmu, who comest forth from Het-Ptah-ka, I have done neither harm nor ill."[29]

Notes

- ↑ Heiroglyphs can be found in Collier and Manley (27, 29, 154). Some additional variants exist, so we have chosen to follow Budge's (1969) listing of the most common ones (Vol. I, 416).

- ↑ Information taken from phonetic symbols for Ma'at, and explanations on how to pronounce based upon modern reals, revealed in (Collier and Manley pp. 2-4, 154)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 417)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 418)

- ↑ (Strudwick p. 106)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 400)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ↑ http://www.wsu.edu:8000/~dee/EGYPT/MAAT.HTM

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 418)

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

- ↑ Pinch, 15; Wilkinson, 150.

- ↑ A. G. McDowell, "Jurisdiction in the Workmen's Community of Deir el-Medîna" [diss.], Egyptologische Uitgaven (5), Leiden, 1990. 23.

- ↑ Frankfort, 54.

- ↑ Assmann, 179.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 150.

- ↑ Frankfort, 62.

- ↑ Frankfort, 77.

- ↑ See Russ VerSteeg, Law in Ancient Egypt 19 (Carolina Academic Press 2002)

- ↑ Frankfort, 77.

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 417)

- ↑ Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 416)

- ↑ The Egyptian Book of the Dead, translated by Budge, 347-349. A strong parallel can be made between this confessional list and the "42 Negative Confessions" found in the Nebseni Papyrus, quoted in Budge's The Egyptian Book of the Dead, 350-351. Both retrieved July 21, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Collier, Mark and Manly, Bill. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520239490.

- Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Mancini, Anna. Ma'at Revealed: Philosophy of Justice in Ancient Egypt. New York: Buenos Books America, 2004. ISBN 1932848290.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Strudwick, Helen (General Editor). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Singapore: De Agostini UK, 2006. ISBN 1904687997.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

External links

- Principles of Ma'at (negative confessions) - Retrieved July 22, 2007

- Egypt: Law and the Legal System in Ancient Egypt by Mark Andrews - Retrieved July 22, 2007

- Ma'at at Encyclopdeia Mythica - Retrieved July 22, 2007

| Topics about Ancient Egypt edit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Places: Nile river | Niwt/Waset/Thebes | Alexandria | Annu/Iunu/Heliopolis | Luxor | Abdju/Abydos | Giza | Ineb Hedj/Memphis | Djanet/Tanis | Rosetta | Akhetaten/Amarna | Atef-Pehu/Fayyum | Abu/Yebu/Elephantine | Saqqara | Dahshur | |||

| Gods associated with the Ogdoad: Amun | Amunet | Huh/Hauhet | Kuk/Kauket | Nu/Naunet | Ra | Hor/Horus | Hathor | Anupu/Anubis | Mut | |||

| Gods of the Ennead: Atum | Shu | Tefnut | Geb | Nuit | Ausare/Osiris | Aset/Isis | Set | Nebet Het/Nephthys | |||

| War gods: Bast | Anhur | Maahes | Sekhmet | Pakhet | |||

| Deified concepts: Chons | Maàt | Hu | Saa | Shai | Renenutet| Min | Hapy | |||

| Other gods: Djehuty/Thoth | Ptah | Sobek | Chnum | Taweret | Bes | Seker | |||

| Death: Mummy | Four sons of Horus | Canopic jars | Ankh | Book of the Dead | KV | Mortuary temple | Ushabti | |||

| Buildings: Pyramids | Karnak Temple | Sphinx | Great Lighthouse | Great Library | Deir el-Bahri | Colossi of Memnon | Ramesseum | Abu Simbel | |||

| Writing: Egyptian hieroglyphs | Egyptian numerals | Transliteration of ancient Egyptian | Demotic | Hieratic | |||

| Chronology: Ancient Egypt | Greek and Roman Egypt | Early Arab Egypt | Ottoman Egypt | Muhammad Ali and his successors | Modern Egypt | |||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.