Libya

- This article is about the country of Libya. For other uses of the term, see Libya (disambiguation).

| الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية العظمى Al-Jamāhīriyyah al-`Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah aš-Ša`biyyah al-Ištirākiyyah al-`Udhmā Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Allahu Akbar (Arabic) God is Great | |||||

| Capital | Tripoli 32°54′N 13°11′E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||

| Government | Jamahiriya | ||||

| - Leader and Guide of the Revolution | Muammar al-Gaddafi | ||||

| - Head of State | Zenati Muhammad az-Zenati | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Baghdadi Mahmudi | ||||

| Independence | |||||

| - relinquished by Italy | February 10 1947 | ||||

| - from France/UK under UN Trusteeship | December 24 1951 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 1,759,540 km² (17th) 679,359 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2006 census | 5,670,6881 | ||||

| - Density | 3.2/km² 8.4/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $74.97 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $12,700 | ||||

| HDI (2005) | |||||

| Currency | Dinar (LYD)

| ||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .ly | ||||

| Calling code | +218 | ||||

Libya (Arabic: ليبيا Lībiyā; Libyan vernacular: Lībya; Amazigh: ⵍⵉⴱⵢⴰ), officially the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya ( الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الإشتراكية العظمى Al-Jamāhīriyyah al-`Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah aš-Ša`biyyah al-Ištirākiyyah al-`Udhmā), is a country in North Africa. Bordering the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Libya lies between Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west. With an area of almost 1.8 million square kilometres (700,000 sq mi), 90% of which is desert, Libya is the fourth largest country in Africa by area, and the 17th largest in the world.[1] The capital, Tripoli, is home to 1.7 million of Libya's 5.7 million people. The three traditional parts of the country are Tripolitania, the Fezzan and Cyrenaica.

The name "Libya" is an indigenous (i.e. Berber) one, which is already attested in Egyptian texts as ![]() , R'bw (= Libu), which refers to one of the tribes of Berber peoples living west of the Nile. In Greek the tribesmen were called Libyes and their country became "Libya", although in ancient Greece the term had a broader meaning, encompassing all of North Africa west of Egypt. Later on, at the time of Ibn Khaldun, the same, big tribe was known as Lawata[citation needed].

, R'bw (= Libu), which refers to one of the tribes of Berber peoples living west of the Nile. In Greek the tribesmen were called Libyes and their country became "Libya", although in ancient Greece the term had a broader meaning, encompassing all of North Africa west of Egypt. Later on, at the time of Ibn Khaldun, the same, big tribe was known as Lawata[citation needed].

Libya has one of the highest Gross Domestic Products per person in Africa, largely because of its large petroleum reserves.[2][3]

The country is led by Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi, whose foreign policy has often brought him into conflict with the West and governments of other African countries. However, Libya publicly gave up any nuclear aspirations after the US invasion of Iraq, and Libya's foreign relations today are less contentious.

History of Libya

Archaeological evidence indicates that from as early as the 8th millennium B.C.E., Libya's coastal plain was inhabited by a Neolithic people who were skilled in the domestication of cattle and the cultivation of crops.[4] This culture flourished for thousands of years in the region, until they were displaced or absorbed by the Berbers. The area known in modern times as Libya was later occupied by a series of peoples, with the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Vandals and Byzantines ruling all or part of the area. Although the Greeks and Romans left ruins at Cyrene, Leptis Magna and Sabratha, little other evidence remains of these ancient cultures.

The Phoenicians were the first to establish trading posts in Libya, when the merchants of Tyre (in present-day Lebanon) developed commercial relations with the Berber tribes and made treaties with them to ensure their cooperation in the exploitation of raw materials.[5][6] By the 5th century B.C.E., Carthage, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, had extended its hegemony across much of North Africa, where a distinctive civilisation, known as Punic, came into being. Punic settlements on the Libyan coast included Oea (Tripoli), Libdah (Leptis Magna) and Sabratha. All these were in an area that was later called Tripolis, or "Three Cities". Libya's current-day capital Tripoli takes its name from this.

The Greeks conquered Eastern Libya when, according to tradition, emigrants from the crowded island of Thera were commanded by the oracle at Delphi to seek a new home in North Africa. In 631 B.C.E., they founded the city of Cyrene.[7] Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area: Barce (Al Marj); Euhesperides (later Berenice, present-day Benghazi); Teuchira (later Arsinoe, present-day Tukrah); and Apollonia (Susah), the port of Cyrene. Together with Cyrene, they were known as the Pentapolis (Five Cities).

The Romans unified both regions of Libya, and for more than 400 years Tripolitania and Cyrenaica became prosperous Roman provinces.[8] Roman ruins, such as those of Leptis Magna, attest to the vitality of the region, where populous cities and even small towns enjoyed the amenities of urban life. Merchants and artisans from many parts of the Roman world established themselves in North Africa, but the character of the cities of Tripolitania remained decidedly Punic and, in Cyrenaica, Greek. Arabs conquered Libya in the 7th century AD. In the following centuries, many of the indigenous peoples adopted Islam, and also the Arabic language and culture. The Ottoman Turks conquered the country in the mid-16th century, and the three States or "Wilayat" of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan (which make up Libya) remained part of their empire with the exception of the virtual autonomy of the Karamanlis who ruled from 1711 until 1835 mainly in Tripolitania but had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well, at the peak their reign (mid 18th century). This constituted a first glimpse in recent history of the united and independent Libya that was to re-emerge two centuries later. Ironically, reunification came about through the unlikely route of an invasion (Italo-Turkish War, 1911-1912) and occupation starting from 1911 when Italy simultaneously turned the three regions into colonies.[9]

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony (made up of the three Provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). King Idris I, Emir of Cyrenaica, led Libyan resistance to Italian occupation between the two World Wars. From 1943 to 1951, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.[10]

On November 21 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1 1952. Idris represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris. Template:History of Libya

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world's poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's finances, popular resentment began to build over the increased concentration of the nation's wealth in the hands of King Idris and the national elite. This discontent continued to mount with the rise of Nasserism and Arab nationalism throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

On September 1 1969, a small group of military officers led by then 28-year-old army officer Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris. At the time, Idris was in Turkey for medical treatment. His nephew, Crown Prince Sayyid Hasan ar-Rida al-Mahdi as-Sanussi, became King. It was clear that the revolutionary officers who had announced the deposition of King Idris did not want to appoint him over the instruments of state as King. Sayyid quickly found that he had substantially less power as the new King than he had earlier had as a mere Prince. Before the end of September 1, Sayyid Hasan ar-Rida had been formally deposed by the revolutionary army officers and put under house arrest. Meanwhile, revolutionary officers abolished the monarchy, and proclaimed the new Libyan Arab Republic. Gaddafi was, and is to this day, referred to as the "Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official press.[11]

Politics

There are two branches of government in Libya. The "revolutionary sector" comprises Revolutionary Leader Gaddafi, the Revolutionary Committees and the remaining members of the 12-person Revolutionary Command Council, which was established in 1969.[12] The historical revolutionary leadership is not elected and cannot be voted out of office; they are in power by virtue of their involvement in the revolution. The revolutionary sector dictates the decision-making power of the second sector, the "Jamahiriya Sector".

Constituting the legislative branch of government, this sector comprises Local People's Congresses in each of the 1,500 urban wards, 32 Sha'biyat People's Congresses for the regions, and the National General People's Congress. These legislative bodies are represented by corresponding executive bodies (Local People's Committees, Sha'biyat People's Committees and the National General People's Committee/Cabinet).

Every four years, the membership of the Local People's Congresses elects their own leaders and the secretaries for the People's Committees, sometimes after many debates and a critical vote. The leadership of the Local People's Congress represents the local congress at the People's Congress of the next level. The members of the National General People's Congress elect the members of the National General People's Committee (the Cabinet) at their annual meeting.

The government controls both state-run and semi-autonomous media. In cases involving a violation of "certain taboos", the private press, like The Tripoli Post, has been censored,[13] although articles that are critical of policies have been requested and intentionally published by the revolutionary leadership itself as a means of initiating reforms.

Political parties were banned by the 1972 Prohibition of Party Politics Act Number 71.[14] According to the Association Act of 1971, the establishment of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) is allowed. However, because they are required to conform to the goals of the revolution, their numbers are small in comparison with those in neighbouring countries. Trade unions do not exist,[15] but numerous professional associations are integrated into the state structure as a third pillar, along with the People's Congresses and Committees. These associations do not have the right to strike. Professional associations send delegates to the General People's Congress, where they have a representative mandate.

Foreign relations

Libya's foreign policies have undergone much fluctuation and change since the state was proclaimed on Christmas Eve, 1951. As a Kingdom, Libya maintained a definitively pro-Western stance, yet was recognized as belonging to the conservative traditionalist bloc in the League of Arab States (Arab League), of which it became a member in 1953.[16] The government was in close alliance with Britain and the United States; both countries maintained military base rights in Libya. Libya also forged close ties with France, Italy, Greece, and established full diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1955.

Although the government supported Arab causes, including the Moroccan and Algerian independence movements, it took little active part in the Arab-Israeli dispute or the tumultuous inter-Arab politics of the 1950s and early 1960s. The Kingdom was noted for its close association with the West, while it steered an essentially conservative course at home.[17]

After the 1969 coup, Gaddafi closed American and British bases and partially nationalized foreign oil and commercial interests in Libya. He also played a key role in promoting oil embargoes as a political weapon for challenging the West, hoping that an oil price rise and embargo in 1973 would persuade the West, especially the United States, to end support for Israel. Gaddafi rejected both Eastern (Soviet) communism and Western (United States) capitalism and claimed he was charting a middle course for his government.[18]

In the 1980s, Libya increasingly distanced itself from the West, and was accused of committing mass acts of state sponsored terrorism. When evidence of Libyan complicity was discovered in the Berlin discotheque terrorist bombing that killed two American servicemen, the United States responded by launching an aerial bombing attack against targets near Tripoli and Benghazi in April 1986.[19]

In 1991, two Libyan intelligence agents were indicted by federal prosecutors in the U.S. and Scotland for their involvement in the December 1988 bombing of Pan Am flight 103. Six other Libyans were put on trial in absentia for the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772. The UN Security Council demanded that Libya surrender the suspects, cooperate with the Pan Am 103 and UTA 772 investigations, pay compensation to the victims' families, and cease all support for terrorism. Libya's refusal to comply led to the approval of UNSC Resolution 748 on March 31, 1992, imposing sanctions on the state designed to bring about Libyan compliance. Continued Libyan defiance led to further sanctions by the UN against Libya in November 1993.[20]

In 2003, more than a decade after the sanctions were put in place, Libya began to make dramatic policy changes vis-à-vis the Western world with the open intention of pursuing a Western-Libyan détente. The Libyan government announced its decision to abandon its weapons of mass destruction programs and pay almost 3 billion US dollars in compensation to the families of Pan Am flight 103 as well as UTA Flight 772.[21] The decision was welcomed by many western nations and was seen as an important step for Libya toward rejoining the international community.[22] Since 2003 the country has made efforts to normalize its ties with the European Union and the United States and has even coined the catchphrase, 'The Libya Model', an example intended to show the world what can be achieved through negotiation rather than force when there is goodwill on both sides.

HIV trials (1999–current)

Five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor were charged with intentionally infecting 426 Libyan children with HIV at a Benghazi children hospital, as part of a supposed plot by the West to destabilize the regime. Initially there were 23 accused Bulgarians and many Libyan health officials but the investigation narrowed the number to five nurses, two doctors, a Bulgarian, a Palestinian, and a number of Libyan health officials. The Bulgarians and the Palestinian had their lawyers present in all trial sessions as well as attorneys from Lawyers Without Borders, although they were not allowed to see their lawyers or even to talk to Bulgarian diplomats during the first year and a half of their arrest, when they were allegedly tortured with beatings and electroshocks. The nurses appeared healthy throughout the trial, and were occasionally seen smiling, but they were subjected to enormous psychological stress, and as a result their health deteriorated and even one of the nurses tried to commit suicide to avoid being tortured. [2]

The Bulgarian ambassador to Libya, Mr. Zdravko Velev, attended almost all trial sessions, as did diplomats from 13 other countries. Two Amnesty International officers also attended the trial as observers. Television crews from Bulgarian TV covered the late sessions of the trial, although at some occasions Bulgarian journalists were refused Lybian entry visa and as a result they were prevented from covering certain court hearings. In 2004, the court cleared one Bulgarian doctor, Dr. Zdravko Georgiev, who was found guilty only of illegal transactions in foreign currency and was sentenced to four years in prison plus a fine of 600 dinars. As he had already been in Libyan custody for more than five years and over served his sentence, he was released from prison, but not allowed to leave Libya for next three years. He lived at the Bulgarian embassy and visited the nurses weekly. The remaining five nurses and the Palestinian doctor were sentenced to death. After a retrial in late 2006, they were again sentenced to death. The court's methods were criticized by a number of human rights organizations, and its verdicts condemned by the United States and the European Union.[23] However, on 17 July, 2007, the sentences were commuted to life imprisonment.[24] After prolonged and complex negotiations with the participation of the European Union, Germany, France etc. on 24 July 2007, all five Bulgarian nurses and the Palestinian doctor were released and arrived in Bulgaria.[25] Their release may have been exchanged against a contract for the construction of a nuclear plant by France.

Human rights

According to the U.S. Department of State’s annual human rights report for 2004, Libya’s authoritarian regime continued to have a poor record in the area of human rights. Some of the numerous and serious abuses on the part of the government include poor prison conditions, arbitrary arrest and detention, prisoners held incommunicado, and political prisoners held for many years without charge or trial. The judiciary is controlled by the state, and there is no right to a fair public trial. Libyans do not have the right to change their government. Freedom of speech, press, assembly, association, and religion are restricted. Independent human rights organizations are prohibited. Ethnic and tribal minorities suffer discrimination, and the state continues to restrict the labor rights of foreign workers.

In 2005, the Freedom House rated political rights in Libya as "7" (1 representing the most free and 7 the least free rating), civil liberties as "7" and gave it the freedom rating of "Not Free"[26], although the organisation itself has been criticized as politically slanted. See Freedom House#Criticism and praise

Municipalities

Libya was divided into several governorates (muhafazat) [3] before being split into 25 municipalities (baladiyat), see map of 25 baladiyat in Municipalities of Libya.[27] Recently, Libya was divided into thirty two sha'biyah.[28][29]. Then these got further rearanged into twenty two. The following list and map show the previous arrangement which is slightly different than the current one.[30]

| The 32 municipalities are: | ||

| 1 Ajdabiya | 17 Ghat | |

| 2 Al Butnan | 18 Ghadamis | |

| 3 Al Hizam Al Akhdar | 19 Gharyan | |

| 4 Al Jabal al Akhdar | 20 Murzuq | |

| 5 Al Jfara | 21 Mizdah | |

| 6 Al Jufrah | 22 Misratah | |

| 7 Al Kufrah | 23 Nalut | |

| 8 Al Marj | 24 Tajura Wa Al Nawahi AlArba' | |

| 9 Al Murgub | 25 Tarhuna Wa Msalata | |

| 10 An Nuqat al Khams | 26 Tarabulus (Tripoli) | |

| 11 Al Qubah | 27 Sabha | |

| 12 Al Wahat | 28 Surt | |

| 13 Az Zawiyah | 29 Sabratha Wa Surman | |

| 14 Benghazi | 30 Wadi Al Hayaa | |

| 15 Bani Walid | 31 Wadi Al Shatii | |

| 16 Darnah | 32 Yafran | |

Geography

Libya extends over 1,759,540 square kilometres (679,182 sq. mi), making it the 17th largest nation in the world by size. Libya is somewhat smaller than Indonesia, and roughly the size of the US state of Alaska. It is bound to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, the west by Tunisia and Algeria, the southwest by Niger, the south by Chad and Sudan and to the east by Egypt. At 1770 kilometres (1100 miles), Libya's coastline is the longest of any African country bordering the Mediterranean.[32][33] The climate is mostly dry and desert-like in nature. However, the northern regions enjoy a milder Mediterranean climate.

Natural hazards come in the form of hot, dry, dust-laden sirocco (known in Libya as the gibli). This is a southern wind blowing from one to four days in spring and autumn. There are also dust storms and sandstorms. Oases can also be found scattered throughout Libya, the most important of which are Ghadames and Kufra as well as others.

Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert, which covers much of eastern Libya, is one of the most arid places on earth. In places, decades may pass without rain, and even in the highlands rainfall happens erratically, once every 5–10 years. At Uweinat, the last recorded rainfall was in September 1998.[34] There is a large depression, the Qattara Depression, just to the south of the northernmost scarp, with Siwa oasis at its western extremity. The depression continues in a shallower form west, to the oases of Jaghbub and Jalo.

Likewise, the temperature in the Libyan desert can be extreme; in 1922, the town of Al 'Aziziyah, which is located west of Tripoli, recorded an air temperature of 57.8 °C (136.0 °F), generally accepted as the highest recorded naturally occurring air temperature reached on Earth.[35]

There are a few scattered uninhabited small oases, usually linked to the major depressions, where water can be found by digging to a few feet in depth. In the west there is a widely dispersed group of oases in unconnected shallow depressions, the Kufra group, consisting of Tazerbo, Rebiana and Kufra.[34] Aside from the scarps, the general flatness is only interrupted by a series of plateaus and massifs near the centre of the Libyan Desert, around the convergence of the Egyptian-Sudanese-Libyan Borders.

Slightly further to the south are the massifs of Arkenu, Uweinat and Kissu. These granite mountains are very ancient, having formed much before the sandstones surrounding them. Arkenu and Western Uweinat are ring complexes very similar to those in the Air Mountains. Eastern Uweinat (the highest point in the Libyan Desert) is a raised sandstone plateau adjacent to the granite part further west.[34] The plain to the north of Uweinat is dotted with eroded volcanic features.

With the discovery of oil in the 1950s also came the discovery of a massive aquifer underneath much of the country. The water in this aquifer pre-dates the last ice ages and the Sahara desert itself.[36] The country is also home to the Arkenu craters, double impact craters found in the desert.

Economy

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which constitute practically all export earnings and about one-quarter of gross domestic product (GDP). These oil revenues and a small population give Libya one of the highest GDPs per person in Africa and have allowed the Libyan state to provide an extensive and impressive level of social security, particularly in the fields of housing and education.[37]

Compared to its neighbours, Libya enjoys an extremely low level of both absolute and relative poverty. Libyan officials in the past three years have carried out economic reforms as part of a broader campaign to reintegrate the country into the global capitalist economy.[38] This effort picked up steam after UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and as Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction.[39]

Libya has begun some market-oriented reforms. Initial steps have included applying for membership of the World Trade Organisation, reducing subsidies, and announcing plans for privatisation.[40] The non-oil manufacturing and construction sectors, which account for about 20% of GDP, have expanded from processing mostly agricultural products to include the production of petrochemicals, iron, steel and aluminium. Climatic conditions and poor soils severely limit agricultural output, and Libya imports about 75% of its food.[38] Water is also a problem, with some 28% of the population not having access to safe drinking water in 2000.[41]

Under the previous Prime Minister, Shukri Ghanem, and current prime minister Baghdadi Mahmudi, Libya is undergoing a business boom. Many government-run industries are being privatised. Most US sanctions have been lifted; and as of May 2006, the remaining vestiges are scheduled for removal pending US Congressional approval. Many international oil companies have returned to the country, including oil giants Shell and ExxonMobil.[42] Tourism is on the rise, bringing increased demand for hotel accommodation and for capacity at airports such as Tripoli International. A multi-million dollar renovation of Libyan airports has recently been approved by the government to help meet such demands.[43] At present 130,000 people visit the country annually; the Libyan government hopes to increase this figure to an ambitious 1,000,000 by 2015.[44]

Demographics

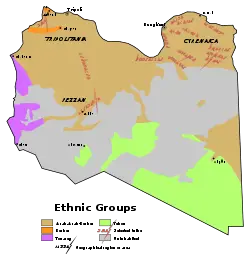

Libya has a small population within its large territory, with a population density of about 3 people per square kilometre (8.5/mi²) in the two northern regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, and less than one person per square kilometre (1.6/mi²) elsewhere. Libya is thus one of the least dense nations by area in the world.[45] 90% of the people live in less than 10% of the area, mostly along the coast. More than half the population is urban, concentrated to a greater extent, in the two largest cities, Tripoli and Benghazi.[46] Native Libyans are a mixture of indigenous Berber peoples and the later arriving Arabs.

A large number of Libyans are called Khoulougli (Sons of Soldiers) who descended from marriages of Ottoman Turkish empire soldiers to native Libyan women. They are mainly found in Misrata (200 km west of Tripoli), Tajoura (Suburb of Tripoli), and Zawiya (about 50 km West of Tripoli). For a long time they were exempt from tax and had the right to bear arms. Now they have merged into the mainly Arab population but can be distinguished easily by complexion and family name.[citation needed]

There are small Tuareg (a Berber population) and Tebu tribal groups concentrated in the south, living nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles. Among foreign residents, the largest groups are citizens of other African nations, including North Africans (primarily Egyptians and Tunisians), and Sub-Saharan Africans.[47] According to the CIA Factbook, Libyan Berbers and Arabs constitute 97% of the population; the other 3% are Greeks, Maltese, Italians, Egyptians, Afghanis, Turks, Indians, and Sub-Saharan Africans.[48]

The main language spoken in Libya is Arabic, which is also the official language. Tamazight (i.e. Berber languages), which do not have official status, are spoken by Libyan Berbers.[49] Berber speakers live above all in the Jebel Nafusa region (Tripolitania), the town of Zuwarah on the coast, and the city-oases of Ghadames, Ghat and Awjila. In addition, Tuaregs speak Tamahaq, the only known Northern Tamasheq language. Italian and English are sometimes spoken in the big cities, although Italian speakers are mainly among the older generation.

Family life is important for Libyan families, the majority of which live in apartment blocks and other independent housing units, with precise modes of housing depending on their income and wealth. Although the Libyan Arabs traditionally lived nomadic lifestyles in tents, they have now settled in various towns and cities.[50] Because of this, their old ways of life are gradually fading out. An unknown small number of Libyans still live in the desert as their families have done for centuries. Most of the population has occupations in industry and services, and a small percentage is in agriculture.

Education

Libya's population includes 1.7 million students, over 270,000 of whom study at the tertiary level.[51] Education in Libya is free for all citizens,[52] and compulsory up until secondary level. The literacy rate is the highest in North Africa; over 88% of the population can read and write.[53] After Libya's independence in 1951, its first university, the University of Libya, was established in Benghazi.[54] In academic year 1975/76 the number of university students was estimated to be 13,418. As of 2004, this number has increased to more than 200,000, with an extra 70,000 enrolled in the higher technical and vocational sector.[51] The rapid increase in the number of students in the higher education sector has been mirrored by an increase in the number of institutions of higher education. Since 1975 the number of universities has grown from two to nine and after their introduction in 1980, the number of higher technical and vocational institutes currently stands at 84 (with 12 public universities).[51] Libya's higher education is financed by the public budget. In 1998 the budget allocated for education represented 38.2% of the national budget.[54]

The main universities in Libya are:

- Al Fateh University (Tripoli)

- Garyounis University (Benghazi)

Religion

By far the predominant religion in Libya is Islam with 97% of the population associating with the faith.[55] The vast majority of Libyan Muslims adhere to Sunni Islam, which provides both a spiritual guide for individuals and a keystone for government policy, but a minority (between 5 and 10%) adheres to Ibadism (a branch of Kharijism), above all in the Jebel Nefusa and the town of Zuwarah. This minority, both linguistic and religious, suffers from a lack of consideration by the official authorities.

Before the 1930s, the Sanusi Movement was the primary Islamic movement in Libya. This was a religious revival adapted to desert life. Its zawaayaa (lodges) were found in Tripolitania and Fezzan, but Sanusi influence was strongest in Cyrenaica. Rescuing the region from unrest and anarchy, the Sanusi movement gave the Cyrenaican tribal people a religious attachment and feelings of unity and purpose.[56] This Islamic movement, which was eventually destroyed by both Italian invasion and later the Gaddafi government,[56] was very conservative and somewhat different from the Islam that exists in Libya today. Gaddafi asserts that he is a devout Muslim, and his government is taking a role in supporting Islamic institutions and in worldwide proselytizing on behalf of Islam.[57] Libyan Islam, however, has always been considered traditional, but in no way harsh compared to Islam in other countries. A Libyan form of Sufism is also common in parts of the country.[58]

Other than the overwhelming majority of Sunni Muslims, there are also very small Christian communities, composed almost exclusively of foreigners. There is a small Anglican community, made up mostly of African immigrant workers in Tripoli; it is part of the Egyptian Diocese.[59] There are also an estimated 40,000 Roman Catholics in Libya who are served by two Bishops, one in Tripoli (serving the Italian community) and one in Benghazi (serving the Maltese community).

Libya was until recent times the home of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to at least 300 B.C.E.[60] A series of pogroms beginning in November of 1945 lasted for almost three years, drastically reducing Libya's Jewish population.[61] In 1948, about 38,000 Jews remained in the country. Upon Libya's independence in 1951, most of the Jewish community emigrated. After the Suez Crisis in 1956, all but about 100 Jews were forced to flee.

Culture

Libya is culturally similar to its neighboring Maghrebian states. Libyans consider themselves very much a part of a wider Arab community. The Libyan state tends to strengthen this feeling by considering Arabic as the only official language, and forbidding the teaching and even the use of the Berber language. Libyan Arabs have a heritage in the traditions of the nomadic Bedouin and associate themselves with a particular Bedouin tribe.

As with some other countries in the Arab world, Libya boasts few theatres or art galleries. Public entertainment is almost nonexistent, even in the big cities.[62] Recently however, there has been a revival of the arts in Libya, especially painting: private galleries are springing up to provide a showcase for new talent.[63] Conversely, for many years there have been no public theatres, and only a few cinemas showing foreign films. The tradition of folk culture is still alive and well, with troupes performing music and dance at frequent festivals, both in Libya and abroad. The main output of Libyan television is devoted to showing various styles of traditional Libyan music. Tuareg music and dance are popular in Ghadames and the south. Libyan television programmes are mostly in Arabic with a 30-minute news broadcast each evening in English and French. The government maintains strict control over all media outlets. A new analysis by the Committee to Protect Journalists has found Libya’s media the most tightly controlled in the Arab world.[13] To combat this, the government plans to introduce private media, an initiative intended to bring the country's media in from the cold.[64]

Many Libyans frequent the country's beaches. They also visit Libya's beautifully-preserved archaeological sites—especially Leptis Magna, which is widely considered to be one of the best preserved Roman archaeological sites in the world.[65]

The nation's capital, Tripoli, boasts many good museums and archives; these include the Government Library, the Ethnographic Museum, the Archaeological Museum, the National Archives, the Epigraphy Museum and the Islamic Museum. The Jamahiriya Museum, built in consultation with UNESCO, may be the country's most famous. It houses one of the finest collections of classical art in the Mediterranean.[66]

See also

- List of famous people from Libya

- Military of Libya

Template:Libyan topics

International rankings

| Organisation | Survey | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Heritage Foundation/The Wall Street Journal | 2006 Index of Economic Freedom | 152 out of 157 |

| The Economist | The World in 2005 - Worldwide quality-of-life index, 2005 | 70 out of 111 |

| Energy Information Administration | Greatest Oil Reserves by Country, 2006 | 9 out of 20 |

| Reporters Without Borders | Press Freedom Index (2005) | 162 out of 167 |

| Transparency International | Corruption Perceptions Index 2005 | 117 out of 158 |

| United Nations Development Programme | Human Development Index 2005 | 58 out of 177 |

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ U.N. Demographic Yearbook, (2003), "Demographic Yearbook (3) Pop., Rate of Pop. Increase, Surface Area & Density", United Nations Statistics Division, Accessed July 15 2006

- ↑ Annual Statistical Bulletin, (2004), "World proven crude oil reserves by country, 1980–2004", O.P.E.C., Accessed July 20 2006

- ↑ World Economic Outlook Database, (April, 2006), "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects", International Monetary Fund, Accessed July 15 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Early History of Libya", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 11 2006

- ↑ Herodotus, (c.430 B.C.E.), "'The Histories', Book IV.42–43" Fordham University, New York, Accessed July 18 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Tripolitania and the Phoenicians", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 11 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Cyrenaica and the Greeks", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 11 2006

- ↑ Heuser, Stephen, (July 24 2005), "When Romans lived in Libya", The Boston Globe Accessed July 18 2006

- ↑ Country Profiles, (May 16 2006), "Timeline: Libya, a chronology of key events" BBC News, Accessed July 18 2006

- ↑ Hagos, Tecola W., (November 20 2004), "Treaty Of Peace With Italy (1947), Evaluation And Conclusion", Ethiopia Tecola Hagos, Accessed July 18 2006

- ↑ US Department of State's Background Notes, (Nov 2005) "Libya - History", U.S. Dept. of State, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Government and Politics of Libya", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Special Report 2006, (May 2 2006), "North Korea Tops CPJ list of '10 Most Censored Countries'", Committee to Protect Journalists, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Case Study: Libya, (2001), "Political Culture", Educational Module on Chemical & Biological Weapons Nonproliferation, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Hodder, Kathryn, (2000), "Violations of Trade Union Rights", Social Watch Africa, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Independent Libya", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Abadi, Jacob (2000), "Pragmatism and Rhetoric in Libya's Policy Toward Israel", The Journal of Conflict Studies: Volume XX Number 1 Fall 2000, University of New Brunswick, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, (2001–2005), "Qaddafi, Muammar al-", Bartleby Books, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Boyne, Walter J., (March, 1999), "El Dorado Canyon", Air Force Association Journal, Vol. 82, No. 3, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ (2003), "Libya", Global Policy Forum, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Marcus, Jonathan, (May 15, 2006), "Washington's Libyan fairy tale", BBC News, Accessed July 15 2006

- ↑ U.K. Politics, (March 25, 2004), "Blair hails new Libyan relations", BBC news, Accessed July 15 2006

- ↑ December 19, 2006 "Statement by Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner on Libyan Court verdict on the Benghazi case".

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/africa/07/17/libya.medics.reut/index.html

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6912965.stm

- ↑ Freedom in the World 2006 (PDF). Freedom House (2005-12-16). Retrieved 2006-07-27.

See also Freedom in the World 2006, List of indices of freedom - ↑ Lahmeyer, Jan, (November 26 2004), "Historical demographical data of the administrative division", Universiteit Utrecht, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Jamahiriya News Agency, (July 19 2004), "Masses of the Basic People's Congresses select their Secretariats and People's Committees" Mathaba News, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ (Arabic) "Municipalities of Libya", Website of the General People's Committee of Libya Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ [1] شعبيات الجماهيرية العظمى - Sha'biyat of Great Jamahiriya, Accessed July 6 2007

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Climate & Hydrology of Libya", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 15 2006

- ↑ (2005), "Demographics of Libya", Education Libya, Accessed June 29 2006

- ↑ (July 20 2006), "Field Listings - Coastlines", CIA World Factbook, Accessed July 23 2006

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Zboray, András, "Flora and Fauna of the Libyan Desert", Fliegel Jezerniczky Expeditions, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Hottest Place, "El Azizia Libya, 'How Hot is Hot?'", Extreme Science, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ ""Fossil Water" in Libya", NASA, Accessed Mar 24, 2007

- ↑ United Nations Economic & Social Council, (Feb 16 1996), "Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Report", Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 The World Factbook, (2006), "Economy - Libya", CIA World Factbook, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ W.M.D., (2003), "Libya Special Weapons News", Global Security Report, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Reuters, (July 28 2004), "Libya to start WTO membership talks", Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa, Accessed July 16 2006

- ↑ (2001), "Safe Drinking Water", WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, Accessed October 8 2006

- ↑ Volume: 23, No. 27, (2006), "Shell returns to Libya with gas exploration pact", Oil & Gas Worldwide News, Accessed July 14 2006

- ↑ Jawad, Rana, (May 31 2006), "Libyan aviation ready for take-off" BBC News, Accessed July 22 2006

- ↑ Phoenicia Group, (Mar 20, 2007), "Libya Plans Ambitious Tourism Makeover; Predicts Free Zones Will Spur Investment", Yahoo Finance, Accessed Mar 20 2007

- ↑ Earth Trends, Environmental Information, (2004), "Population: Population density", World Resources Institute, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Al-Amari, Mailud, (Nov 2004), "Population Dynamics and Fertility Trends in Libya", American Public Health Association, Accessed July 17 2006

- ↑ Libya Demographics and Geography, (2005), "Libya - Population" The Columbia Gazetteer of the World, Accessed July 17 2006

- ↑ The World Factbook, (2006), "People - Libya", CIA World Factbook, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Anderson, Lisa, (2006), "'Libya', III. People, B. Religion & Language", MSN Encarta, Accessed July 17 2006

- ↑ Al-Hawaat, Dr. Ali, (1994), "The Family and the work of women, A study in the Libyan Society" National Center for Research and Scientific Studiesof Libya, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Clark, Nick, (July 2004), "Education in Libya", World Education News and Reviews, Volume 17, Issue 4, Accessed July 22 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Education of Libya", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 22 2006

- ↑ (Sep 14, 2006), "Libya Cuts Illiteracy Rate to 11.9 Percent: Census", Reuters, Accessed September 15 2006

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 El-Hawat, Ali, (2000), "Country Higher Education Profiles - Libya", International Network for Higher Education in Africa", Accessed July 22 2006

- ↑ Religious adherents by location, "'42,000 religious geography and religion statistics', Libya" Adherents.com, Accessed July 15, 2006

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1989), "The Sanusis", U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed July 22, 2006

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1989), "Islam in Revolutionary Libya", US Library of Congress, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Libya - Religion, (July 8 2006), "Sufi Movement to be involved in Libya" Arabic News, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ (2004), "International Religious Freedom Report: Libya" Jewish Virtual Library, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ The World Jewish Congress, "History of the Jewish Community in Libya", University of California at Berkeley, Accessed July 16 2006

- ↑ Harris, David A. (2001), "In the Trenches: Selected Speeches and Writings of an American Jewish Activist", 1979–1999, pp. 149–150

- ↑ News and Trends: Africa, (September 17 1999), "Libya looking at economic diversification" Alexander's Gas & Oil Connections, Accessed July 19 2006.

- ↑ About Libya, "Libya Today", Discover Libya Travel, Accessed July 14 2006.

- ↑ (Jan 30 2006), "Libya to allow independent media", Middle East Times, Accessed July 21 2006

- ↑ Donkin, Mike, (July 23 2005), "Libya's tourist treasures", BBC News, Accessed July 19 2006

- ↑ Bouchenaki, Mounir, (1989), "The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Museum: a first in the Arab world", UNESCO, Museum Architecture: beyond the <<temple>> and ... beyond, Accessed July 19 2006

- Libya, Anthony Ham, Lonely Planet Publications, 2002, ISBN 0-86442-699-2

- Libya Handbook, Jamez Azema, Footprint Handbooks, 2001, ISBN 1-900949-77-6

- Harris, David A. (2001). In the Trenches: Selected Speeches and Writings of an American Jewish Activist, 1979–1999. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. ISBN 0-88125-693-5

- Wright, John L. Nations of the Modern World: Libya, Ernest Benn Ltd, 1969

- Template:CIAfb

- This article contains material from the US Department of State's Background Notes which, as a US government publication, is in the public domain.

External links

- General People's Committee (The Cabinet)

- The People's Committee of Foreign Affairs

- Libya in Encyclopaedia Britannica Online

- Worldstatesmen.org's History and list of rulers of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, Fezzan and Libya (before and after unification).

- Zum.de's History of Cyrenaica.

- Population of Libyan municipalities and cities in different censuses and estimations

- Libya-Watanona.com's page includes pages on historic Libyans and links to websites of contemporary famous ones.

- Information on Libyan high education institutions

- Libyan Liaison Office, Washington D.C.

- Libyan People's Bureau (Libyan Embassy), Ottawa

- Libyan Cultural Affairs, London.

- Libyan American Chamber of Commerce

- Travel guide to Libya from Wikitravel

- Libyan Arab Airlines

- Libya Forum| A Valuable Resource On Libya News

- Limes Tripolitanus

- (French) (Arabic) (English) News and Views of the Maghreb

- 20 digital objects in The European Library

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.