John Dee

John Dee (July 13, 1527–1609) was a noted Welsh mathematician, geographer, occultist, astronomer, and astrologer, whose expertise in these interrelated fields led him to become a personal consultant to Queen Elizabeth I. Due to his interest in magic and the occult, he also devoted much of his life to alchemy, divination, and Hermetic philosophy.

Dee straddled the worlds of science and magic just as the two disciplines were becoming distinguishable. One of the most learned men of his age, he began his prolific academic career early, lecturing to crowded halls at the University of Paris while still in his twenties. As an natural philosopher, John was an ardent promoter of mathematics, leading to the popularization of geometry as a discipline and to an increased level of respect for mathematics among the general populace. Likewise, he was also a renowned astronomer and a leading expert in navigation, leading to his theoretical and practical involvement in instructing and training many of the British sailors who would take part in England's voyages of discovery. In this capacity, his writings are the first recorded use of the the term "British Empire."

At the same time, he immersed himself deeply into the study of various occult disciplines, including alchemy, magic and Hermetic philosophy. His fascination with such practices, most notably his interest in communing with angels (for the purpose of delving into the mystical fountainhead of creation), was so intense that he devoted the last third of his life almost exclusively to these pursuits. For Dee, as with many of his contemporaries, these activities were not contradictory, but instead were particular aspects of a consistent world-view. Indeed, his fascination with the occult creates a notable parallel with his famed (spiritual) successor, Isaac Newton, a noted scientist whose interest in alchemy caused a biographer to opine: "Newton was not the first of the age of reason: he was the last of the magicians."[1]

Biography

Youth and Education

In 1527, John Dee was born in Tower Ward, London, to a Welsh family, whose surname derived from the Welsh du ("black"). His father Roland was a mercer (an importer and trader of fine cloth) and a minor courtier. Due to his relatively privileged upbringing, young John was free to be educated, first attending the Chelmsford Catholic School and later (1542–1548) St. John's College, Cambridge, where he was awarded with both a bachelor's and a master's degree. His prodigious abilities as a natural philosopher were recognized during his studies, and he was made a founding fellow of Trinity College.

In the late 1540s and early 1550s, he supplemented his education by traveling to Europe, where he studied at Leuven and Brussels, apprenticed himself to Gemma Frisius (a famed Dutch mathematician, cartographer and instrument maker), and became a close friend of the cartographer Gerardus Mercator. From these valuable acquaintanceships, he received both tutelage and state-of-the-art technology, returning to England with an important collection of mathematical and astronomical instruments. Even at this early stage, Dee's interests as a natural philosopher transcended what today would be called "science." As one example, we can turn to his 1552 meeting with Gerolamo Cardano in London: during the latter's sojourn in England, the duo investigated astrology, perpetual motion machines, and also did some experiments upon a gem purported to have magical properties.[2] Likewise, his interest in alchemy (as evidenced in diary entries ennumerating his reading lists) was also well established by this point.[3]

Early Professional Life

Dee was offered a readership in mathematics at Oxford in 1554, which he declined; he was already occupied with writing and was perhaps hoping for a better position in the royal court.[4] Such an opportunity arose in 1555, when Dee became a member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers, as his father had, through the company's system of patrimony.[5] Unfortunately, this period also saw the first of his run-ins with secular and religious authorities. Specifically, that same year (1555), he was arrested and charged with "calculating" for having cast (presumably inauspicious) horoscopes for Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth; more distressing still, these charges were then expanded to treason against Mary.[4][6] In response, Dee appeared before the high court at the Palace of Westminster's Star Chamber and exonerated himself from the charge of treason. However, it was still suggested that his theories and practices bordered on witchcraft, so he was turned over to the reactionary Catholic Bishop Bonner for a religious inquiry. Eventually, the young scholar cleared his name yet again, and soon became a close associate of Bonner.[4] In both cases, Dee's potent lifelong penchant for secrecy likely worsened matters and left his open to such critiques. Indeed, these two episodes were only the most dramatic in a series of attacks and slanders that dogged Dee throughout his life.

In 1556, John Dee presented Queen Mary with a visionary plan for the preservation of old books, manuscripts and records and the founding of a national library. His far-reaching proposal was both rationally argued and rhetorically passionate:

- Dee uses powerful arguments to enforce his plea, choosing such as would make the most direct appeal to both Queen and people. She will build for herself a lasting name and monument; they will be able all in common to enjoy what is now only the privilege of a few scholars, and even these have to depend on the goodwill of private owners. He proposes first that a commission shall be appointed to inquire what valuable manuscripts exist; that those reported on shall be borrowed (on demand), a fair copy made, and if the owner will not relinquish it, the original be returned. Secondly, he points out that the commission should get to work at once, lest some owners, hearing of it, should hide away or convey away their treasures, and so, he pithily adds, "prove by a certain token that they are not sincere lovers of good learning because they will not share them with others."[7]

Despite (or perhaps because of) the revolutionary nature of his suggestions, his proposal was not taken up.[4] Instead, he found it necessary to expand his personal library at his home in Mortlake, tirelessly acquiring books and manuscripts from England and the European Continent. Dee's library, a notable hub of learning and scholarship outside the university system, became the greatest in England and attracted many scholars.[8]

When Elizabeth took the throne in 1558, Dee became her trusted advisor on astrological and scientific matters, choosing Elizabeth's coronation date himself.[9][10] From the 1550s through the 1570s, he served as an advisor to England's voyages of discovery, providing technical assistance in navigation and ideological backing in the creation of a "British Empire", and was the first to use that term.[11] In 1577, Dee published General and Rare Memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation, a work that set out his vision of a maritime empire and asserted English territorial claims on the New World. Dee was acquainted with Humphrey Gilbert and was close to Sir Philip Sidney and his circle.[11]

In 1564, Dee wrote the Hermetic work Monas Hieroglyphica ("The Hieroglyphic Monad"), an exhaustive Cabalistic interpretation of a glyph of his own design, meant to express the mystical unity of all creation. This work was highly valued by many of Dee's contemporaries, but the loss of the secret oral tradition of Dee's milieu makes the work difficult to interpret today.[12]

He published a "Mathematical Preface" to Henry Billingsley's English translation of Euclid's Elements in 1570, arguing the central importance of mathematics and outlining mathematics' influence on the other arts and sciences.[13] Intended for an audience outside the universities, it proved to be Dee's most widely influential and frequently reprinted work.[14]

Later life

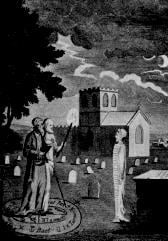

By the early 1580s, Dee was growing dissatisfied with his progress in learning the secrets of nature and with his own lack of influence and recognition. He began to turn towards the supernatural as a means to acquire knowledge. Specifically, he sought to contact angels through the use of a "scryer" or crystal-gazer, who would act as an intermediary between Dee and the angels.[15]

Dee's first attempts were not satisfactory, but, in 1582, he met Edward Kelley (then going under the name of Edward Talbot), who impressed him greatly with his abilities.[16] Dee took Kelley into his service and began to devote all his energies to his supernatural pursuits.[16] These "spiritual conferences" or "actions" were conducted with an air of intense Christian piety, always after periods of purification, prayer and fasting.[16] Dee was convinced of the benefits they could bring to mankind. (The character of Kelley is harder to assess: some have concluded that he acted with complete cynicism, but delusion or self-deception are not out of the question.[17] Kelley's "output" is remarkable for its sheer mass, its intricacy and its vividness.) Dee maintained that the angels laboriously dictated several books to him this way, some in a special angelic or Enochian language.[18][19]

In 1583, Dee met the visiting Polish nobleman Albert Łaski, who invited Dee to accompany him on his return to Poland.[6] With some prompting by the angels, Dee was persuaded to go. Dee, Kelley, and their families left for the Continent in September 1583, but Łaski proved to be bankrupt and out of favour in his own country.[20] Dee and Kelley began a nomadic life in Central Europe, but they continued their spiritual conferences, which Dee recorded meticulously.[18][19] He had audiences with Emperor Rudolf II and King Stephen of Poland in which he chided them for their ungodliness and attempted to convince them of the importance of his angelic communications. He was not taken up by either monarch.[20]

During a spiritual conference in Bohemia, in 1587, Kelley told Dee that the angel Uriel had ordered that the two men should share their wives. Kelley, who by that time was becoming a prominent alchemist and was much more sought-after than Dee, may have wished to use this as a way to end the spiritual conferences.[20] The order caused Dee great anguish, but he did not doubt its genuineness and apparently allowed it to go forward, but broke off the conferences immediately afterwards and did not see Kelley again. Dee returned to England in 1589.[20][21]

Final years

Dee returned to Mortlake after six years to find his library ruined and many of his prized books and instruments stolen.[8][20] He sought support from Elizabeth, who finally made him Warden of Christ's College, Manchester, in 1592. This former College of Priests had been re-established as a Protestant institution by a Royal Charter of 1578.[22]

However, he could not exert much control over the Fellows, who despised or cheated him.[4] Early in his tenure, he was consulted on the demonic possession of seven children, but took little interest in the matter, although he did allow those involved to consult his still extensive library.[4]

He left Manchester in 1605 to return to London.[23] By that time, Elizabeth was dead, and James I, unsympathetic to anything related to the supernatural, provided no help. Dee spent his final years in poverty at Mortlake, forced to sell off various of his possessions to support himself and his daughter, Katherine, who cared for him until the end.[23] He died in Mortlake late in 1608 or early 1609 aged 82 (there are no extant records of the exact date as both the parish registers and Dee's gravestone are missing).[4][24]

Personal life

Dee was married twice and had eight children. Details of his first marriage are sketchy, but is likely to have been from 1565 to his wife's death in around 1576. From 1577 to 1601 Dee kept a meticulous diary.[5] In 1578 he married the twenty-three year old Jane Fromond (Dee was fifty-one at the time). She was to be the wife that Kelley claimed Uriel had demanded that he and Dee share, and although Dee complied for a while this eventually caused the two men to part company.[5] Jane died during the plague in Manchester in 1605, along with a number of his children: Theodore is known to have died in Manchester, but although no records exist for his daughters Madinia, Frances and Margaret after this time, Dee had by this time ceased keeping his diary.[4] His eldest son was Arthur Dee, about whom Dee wrote a letter to his headmaster at Westminster School which echos the worries of boarding school parents in every century; Arthur was also an alchemist and hermetic author.[4] John Aubrey gives the following description of Dee: "He was tall and slender. He wore a gown like an artist's gown, with hanging sleeves, and a slit.... A very fair, clear sanguine complexion... a long beard as white as milk. A very handsome man."[24]

Achievements

Thought

Dee was an intensely pious Christian, but his Christianity was deeply influenced by the Hermetic and Platonic-Pythagorean doctrines that were pervasive in the Renaissance.[25] He believed that number was the basis of all things and the key to knowledge, that God's creation was an act of numbering.[9] From Hermeticism, he drew the belief that man had the potential for divine power, and he believed this divine power could be exercised through mathematics. His cabalistic angel magic (which was heavily numerological) and his work on practical mathematics (navigation, for example) were simply the exalted and mundane ends of the same spectrum, not the antithetical activities many would see them as today.[14] His ultimate goal was to help bring forth a unified world religion through the healing of the breach of the Catholic and Protestant churches and the recapture of the pure theology of the ancients.[9]

Reputation and significance

About ten years after Dee's death, the antiquarian Robert Cotton purchased land around Dee's house and began digging in search of papers and artefacts. He discovered several manuscripts, mainly records of Dee's angelic communications. Cotton's son gave these manuscripts to the scholar Méric Casaubon, who published them in 1659, together with a long introduction critical of their author, as A True & Faithful Relation of What passed for many Yeers between Dr. John Dee (A Mathematician of Great Fame in Q. Eliz. and King James their Reignes) and some spirits.[18] As the first public revelation of Dee's spiritual conferences, the book was extremely popular and sold quickly. Casaubon, who believed in the reality of spirits, argued in his introduction that Dee was acting as the unwitting tool of evil spirits when he believed he was communicating with angels. This book is largely responsible for the image, prevalent for the following two and a half centuries, of Dee as a dupe and deluded fanatic.[25]

Around the same time the True and Faithful Relation was published, members of the Rosicrucian movement claimed Dee as one of their number.[26] There is doubt, however, that an organized Rosicrucian movement existed during Dee's lifetime, and no evidence that he ever belonged to any secret fraternity.[16] Dee's reputation as a magician and the vivid story of his association with Edward Kelley have made him a seemingly irresistible figure to fabulists, writers of horror stories and latter-day magicians. The accretion of false and often fanciful information about Dee often obscures the facts of his life, remarkable as they are in themselves.[27]

A re-evaluation of Dee's character and significance came in the 20th century, largely as a result of the work of the historian Frances Yates, who brought a new focus on the role of magic in the Renaissance and the development of modern science. As a result of this re-evaluation, Dee is now viewed as a serious scholar and appreciated as one of the most learned men of his day.[25][28]

His personal library at Mortlake was the largest in the country, and was considered one of the finest in Europe, perhaps second only to that of de Thou. As well as being an astrological, scientific and geographical advisor to Elizabeth and her court, he was an early advocate of the colonization of North America and a visionary of a British Empire stretching across the North Atlantic.[11]

Dee promoted the sciences of navigation and cartography. He studied closely with Gerardus Mercator, and he owned an important collection of maps, globes and astronomical instruments. He developed new instruments as well as special navigational techniques for use in polar regions. Dee served as an advisor to the English voyages of discovery, and personally selected pilots and trained them in navigation.[4][11]

He believed that mathematics (which he understood mystically) was central to the progress of human learning. The centrality of mathematics to Dee's vision makes him to that extent more modern than Francis Bacon, though some scholars believe Bacon purposely downplayed mathematics in the anti-occult atmosphere of the reign of James I.[29] It should be noted, though, that Dee's understanding of the role of mathematics is radically different from our contemporary view.[14][27][30]

Dee's promotion of mathematics outside the universities was an enduring practical achievement. His "Mathematical Preface" to Euclid was meant to promote the study and application of mathematics by those without a university education, and was very popular and influential among the "mecanicians": the new and growing class of technical craftsmen and artisans. Dee's preface included demonstrations of mathematical principles that readers could perform themselves.[14]

Dee was a friend of Tycho Brahe and was familiar with the work of Copernicus.[4] Many of his astronomical calculations were based on Copernican assumptions, but he never openly espoused the heliocentric theory. Dee applied Copernican theory to the problem of calendar reform. His sound recommendations were not accepted, however, for political reasons.[9]

He has often been associated with the Voynich Manuscript.[16][31] Wilfrid M. Voynich, who bought the manuscript in 1912, suggested that Dee may have owned the manuscript and sold it to Rudolph II. Dee's contacts with Rudolph were far less extensive than had previously been thought, however, and Dee's diaries show no evidence of the sale. Dee was, however, known to have possessed a copy of the Book of Soyga, another enciphered book.[32]

Artifacts

The British Museum holds several items once owned by Dee and associated with the spiritual conferences:

- Dee's Speculum or Mirror (an obsidian Aztec cult object in the shape of a hand-mirror, brought to Europe in the late 1520s), which was once owned by Horace Walpole.

- The small wax seals used to support the legs of Dee's "table of practice" (the table at which the scrying was performed).

- The large, elaborately-decorated wax "Seal of God", used to support the "shew-stone", the crystal ball used for scrying.

- A gold amulet engraved with a representation of one of Kelley's visions.

- A crystal globe, six centimetres in diameter. This item remained unnoticed for many years in the mineral collection; possibly the one owned by Dee, but the provenance of this object is less certain than that of the others.[33]

In December 2004, both a shew stone (a stone used for scrying) formerly belonging to Dee and a mid-1600s explanation of its use written by Nicholas Culpeper were stolen from the Science Museum in London; they were recovered shortly afterwards.[34]

Notes

- ↑ Keynes, John Maynard (1972). ""Newton, The Man"", The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes Volume X, pp. 363-4.

- ↑ Gerolamo Cardano (trans. by Jean Stoner) (2002). De Vita Propria (The Book of My Life). New York: New York Review of Books, viii.

- ↑ Nicholas H. Cluelee, "The Monas Hieroglyphica and the Alchemical Thread of John Dee’s Career," Ambix, Vol. 52, No. 3, November 2005, 197–215. 198.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 A John Dee Chronology, 1509–1609. RENAISSANCE MAN: The Reconstructed Libraries of European Scholars: 1450–1700 Series One: The Books and Manuscripts of John Dee, 1527–1608. Adam Matthew Publications (2005). Retrieved 27 October, 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 (1792)Mortlake. The Environs of London: County of Surrey 1: 364-88.

- ↑ Fell-Smith, Chapter II, accessed at johndee.org. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Books owned by John Dee. St. John's College, Cambridge. Retrieved 26 October, 2006.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Dr. Robert Poole (2005-09-06). John Dee and the English Calendar: Science, Religion and Empire. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 26 October, 2006.

- ↑ Szönyi, György E. (2004). John Dee and Early Modern Occult Philosophy. Literature Compass 1 (1): 1–12.

- ↑ Forshaw, Peter J. (2005). The Early Alchemical Reception of John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica. Ambix 52 (3): 247–269.

- ↑ John Dee (1527–1608): Alchemy - the Beginings of Chemistry. Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester (2005). Retrieved 26 October, 2006.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Stephen Johnston (1995). The identity of the mathematical practitioner in 16th-century England. Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Retrieved 27 October, 2006.

- ↑ Frank Klaassen (2002-08). John Dee's Conversations with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature. Canadian Journal of History.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Calder, I.R.F. (1952). John Dee Studied as an English Neo-Platonist. University of London. Retrieved 26 October, 2006.

- ↑ "Dee, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. (2006). Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved on 27 October.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Meric Casaubon (1659 Republished by Magickal Childe (1992)). A True & Faithful Relation of What passed for many Yeers between Dr. John Dee (A Mathematician of Great Fame in Q. Eliz. and King James their Reignes) and some spirits. ISBN 0-939708-01-9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dee, John. Quinti Libri Mysteriorum.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Mackay, Charles (1852). "4", Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. London: Office of the National Illustrated Library.

- ↑ History of the Alchemy Guild. International Alchemy Guild. Retrieved 26 October, 2006.

- ↑ "John Dee". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th Ed.). (1911). London: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608: Appendix 1. London: Constable and Company.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 John Aubrey (1898). in Rev. Andrew Clark: Brief Lives chiefly of Contemporaries set down John Aubrey between the Years 1669 and 1696. Clarendon Press.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Walter I. Trattner (01-1964). God and Expansion in Elizabethan England: John Dee, 1527–1583. Journal of the History of Ideas 25 (1): 17–34.

- ↑ Ron Heisler (1992). John Dee and the Secret Societies. The Hermetic Journal.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Katherine Neal (1999). The Rhetoric of Utility: Avoiding Occult Associations For Mathematics Through Profitability and Pleasure. University of Sydney. Retrieved 27 October, 2006.

- ↑ Frances A. Yates (1987). Theatre of the World. London: Routledge, 7.

- ↑ Brian Vickers (1992-07). Francis Bacon and the Progress of Knowledge. Journal of the History of Ideas 53 (3): 495–518.

- ↑ Stephen Johnston (1995). Like father, like son? John Dee, Thomas Digges and the identity of the mathematician. Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Retrieved 27 October, 2006.

- ↑ Gordon Rugg (2004-07). The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript. Scientific American. Retrieved 28 October, 2006.

- ↑ Jim Reeds (1996). John Dee and the Magic Tables in the Book of Soyga. Retrieved 8 November, 2006.

- ↑ BSHM Gazetteer — LONDON: British Museum, British Library and Science Museum. British Society for the History of Mathematics (2002-08). Retrieved 27 October, 2006.

- ↑ Adam Fresco (2004-12-11). Museum thief spirits away old crystal ball. The Times. Retrieved 27 October, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackroyd, Peter The House of Doctor Dee Penguin (1993)

- Calder, I.R.F. John Dee Studied as an English Neo-Platonist University of London Dissertation (1952) Available online

- Casaubon, M. A True and Faithful Relation of What Passed for many Yeers Between Dr. John Dee... (1659) repr. "Magickal Childe" ISBN 0-939708-01-9 New York 1992)

- Dee, John Quinti Libri Mysteriorum. British Library, MS Sloane Collection 3188. Also available in a fair copy by Elias Ashmole, MS Sloane 3677.

- Dee, John John Dee's five books of mystery: original sourcebook of Enochian magic: from the collected works known as Mysteriorum libri quinque edited by Joseph H. Peterson, Boston: Weiser Books ISBN 1-57863-178-5.

- Fell Smith, Charlotte John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company (1909) Available online.

- French, Peter J. John Dee: The World of an Elizabethan Magus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (1972)

- Woolley, Benjamin The Queen's Conjuror: The Science and Magic of Dr. John Dee, Adviser to Queen Elizabeth I. New York: Henry Holt and Company (2001)

External links

- Azogue: It is a section of the e-journal Azogue with original reproductions of Dee texts.

- John Dee reports of Dee and Kelley's conversations with Angels edited in PDF by Clay Holden:

- Mysteriorum Liber Primus (with Latin translations)

- Notes to Liber Primus by Clay Holden

- Mysteriorum Liber Secundus

- Mysteriorum Liber Tertius

- The J.W. Hamilton-Jones translation of Monas Hieroglyphica from Twilit Grotto: Archives of Western Esoterica

- The Private Diary of Dr. John Dee And the Catalog of His Library of Manuscripts at Project Gutenberg

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. John Dee at the MacTutor archive

- http://www.maney.co.uk/contents/ambix/52-3 John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica, Ambix Volume 52, Part 3 2005]

- Alchemical Manchester - The Dee Connection -(contemporary article on Dee)

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Dee, John |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dr Dee |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | British mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, occultist, alchemist and philosopher. |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 13 July 1527 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | c. 1608 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Mortlake, Surrey |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.