Imhotep

Imhotep (sometimes spelled Immutef, Im-hotep, or Ii-em-Hotep, Egyptian ii-m-ḥtp *jā-im-ḥatāp meaning "the one who comes in peace") served under the Third Dynasty king Djoser (reigned ca. 2630-2610 B.C.E.)[1] as chancellor to the pharaoh and high priest of the creator god Ptah at Heliopolis. His excellence in practical scholarship has led to the preservation of his reputation as a preeminent architect and physician—arguably the earliest practitioner of each discipline known by name in human history.[2]

<cult>

Imhotep in an Egyptian Context

| Imhotep in hieroglyphs | ||||

|

As an Egyptian culture hero/deity, Imhotep belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.[3] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[4] The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[5] Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[6] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[7] Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[8]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the Hebrews, Mesopotamians and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[9] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[10] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

Biography

As is often the case for individuals whose historical existence was sufficiently remote, little is definitively known about the life of Imhotep, an Egyptian culture hero from the Third Dynasty period. Fortunately, the surviving complex of scribal records, artistic depictions, and mythic accounts paints a relatively consistent picture of the man, allowing us to draw up the following biographical sketch.

Imhotep, often thought to have been a commoner, entered into the service of King Djoser (reigned ca. 2630-2610 B.C.E.)[11] relatively early in life, gradually earning the position of royal chancellor.

Much else 'known' about him is hearsay and conjecture. The Egyptians credited him with many inventions. As one of the officials of the Pharaoh Djosèr he probably designed the Pyramid of Djoser (the Step Pyramid) at Saqqara in Egypt around 2630-2611 B.C.E. [12]. He may have been responsible for the first known use of columns in architecture. He has also been claimed to be the inventor of the Papyrus scroll being its oldest known bearer.

Imhotep is credited with being the founder of Egyptian medicine, and with being the author of a medical treatise remarkable for being devoid of magical thinking, the so-called Edwin Smith papyrus, detailing anatomical observations, ailments, and cures. The surviving papyrus was probably written around 1700 B.C.E. but may be a copy of texts a thousand years older. This attribution of authorship is speculative [13].

The full list of his titles, as preserved on a Third Dynasty stele, includes such epithets as "Chancellor of the King of Lower Egypt; First after the King of Upper Egypt; Administrator of the Great Palace; Hereditary nobleman; High Priest of Heliopolis; Builder; Chief Carpenter; Chief Sculptor and Maker of Vases in Chief."[14]

The knowledge of the location of Imhotep's tomb was lost in antiquity [15] and is still unknown, despite efforts to find it. The general consensus is that it is at Saqqara.

Cultural and Mythological Legacy

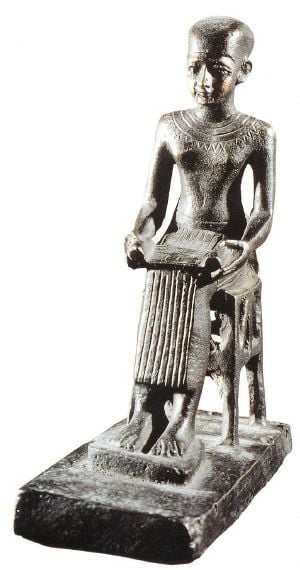

Imhotep is the only mortal to be depicted on the foot-stone of a king's statue and one of a few commoners to be accorded divine status after his death. The centre of his cult was Memphis. From the First Intermediate Period onward Imhotep was also revered as a poet and philosopher. His sayings were famously referred to in poems: I have heard the words of Imhotep and Hordedef with whose discourses men speak so much. [16]

Two thousand years after his death, his status was raised to that of a god. He became the god of medicine and healing. He was linked to Asclepius by the Greeks. The Encyclopedia Britannica says, "The evidence aforded by Egyptian and Greek texts support the view that Imhotep's reputation was very respected in early times... His prestige increased with the lapse of centuries and his temples in Greek times were the centers of medical teachings."

As the "son of Ian", his mother was sometimes said to be Sekhmet, who was often said to be married to Ptah, since she was the patron of Upper Egypt. As he was considered the inventor of healing, he was also sometimes said to be the one who held up Nut (deification of the sky), as the separation of Nut and Geb (deification of the earth) was said to be what held back chaos. Due to the position this would have placed him in, he was also sometimes said to be Nut's son. In artwork he is also linked with Hathor, who was the wife of Ra, Maat, which was the concept of truth and justice, and Amenhotep son of Hapu, who was another deified architect.

It is Imhotep, says Sir William Osler, who was the real Father of Medicine. "The first figure of a physician to stand out clearly from the mists of antiquity."

An inscription from Upper Egypt, dating from the Ptolemaic period, mentions a famine of seven years during the time of Imhotep. According to the inscription, the reigning pharaoh, Djoser, had a dream in which the Nile god spoke to him. Imhotep is credited with helping to solve the famine, and the obvious parallels with the biblical story of Joseph have long been commented upon. [17]. More recently, the Joseph parallels have led some alternative historians to actually identify Imhotep with Joseph, and to argue that the supposedly thousand years separating them are indicative of a faulty chronology. [18].

Notes

- ↑ Dates courtesy of BBC History. A slightly different timeline is suggested by wikipedia. Both retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ William Osler, The Evolution of Modern Medicine, (Kessinger Publishing, 2004). 12. ISBN 1426400217.

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

- ↑ Dates courtesy of BBC History. A slightly different timeline is suggested by wikipedia. Both retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ Ancient Egypt by Barry J. Kemp, Routledge 2005, p.159

- ↑ Fractures: A History and Iconography of Their Treatment By Leonard Francis Peltier, Norman Publishing 1990, p.16

- ↑ Jimmy Dunn, "Imhotep: Doctor, Architect, High Priest, Scribe and Vizier to King Djoser," a feature article for tour-egypt.net. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ The Harper's Lay, ca. 2000 B.C.E.

- ↑ Ancient Egypt by Barry J. Kemp, Routledge 2005, p.159

- ↑ Vandier, La Famine dans l Egypte ancienne

- ↑ Emmet Sweeney, The Genesis of Israel and Egypt, London, 1997

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dennis, James Teackle (translator). The Burden of Isis. 1910. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Klotz, David. Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple. New Haven, 2006. ISBN 0974002526.

- Larson, Martin A. The Story of Christian Origins. 1977. ISBN 0883310902.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.