Igloo

- Quinzhee redirects here.

Origin

An igloo (Inuit language: iglu, Inuktitut syllabics: ᐃᒡᓗ, "house", plural: iglooit or igluit, but in English commonly "igloos"), translated sometimes as "snowhouse," is the Inuit word for house or habitation. As such, the Inuit do not restrict the use of this term exclusively to snow houses but include traditional tents, sod houses, homes constructed of driftwood, and modern buildings.[1][2]

The Igluvijaq (ᐃᒡᓗᕕᔭᖅ) refers specifically to the snowhouse.[3] This is a shelter constructed from blocks of snow, generally in the form of a dome. Although such igloos are usually associated with all Inuit, they were predominantly constructed by people of Canada's Central Arctic and Greenlands Thule area. Other Inuit people tended to use snow to insulate their houses, which were constructed of whalebone and hides.

Snow is used for shelter because the air pockets trapped in it make it an excellent insulator. On the outside, temperatures may be as low as −45 °C (−49.0 °F), but on the inside of an igloo the temperature may range from −7 °C (19 °F) to 16 °C (61 °F) when warmed by body heat alone.[4]

A quinzhee or quinzee (IPA: /ˈkwɪnzi/) is a shelter made by hollowing out a pile of settled snow, and is a temporary shelter. This is in contrast to an igloo, which is made from blocks of snow and can be semi-permanent. The word quinzhee is of Athabaskan origin.[5]

Construction

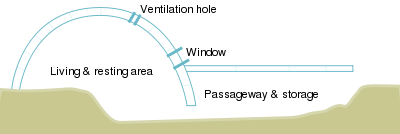

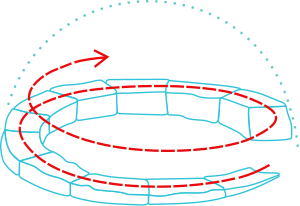

The snow used to build an igloo must have sufficient structural strength to be cut and stacked in the appropriate manner. The best snow to use for this purpose is snow which has been blown by wind, which can serve to compact and interlock the ice crystals. The hole left in the snow where the blocks are cut from is usually used as the lower half of the shelter. Sometimes, a short tunnel is constructed at the entrance to reduce wind and heat loss when the door is opened. Due to snow's excellent insulating properties, inhabited igloos are surprisingly comfortable and warm inside. In some cases a single block of ice is inserted to allow light into the igloo.

Architecturally, the igloo is unique in that it is a dome that can be raised out of independent blocks leaning on each other and polished to fit without an additional supporting structure during construction. The igloo, if correctly built, will support the weight of a person standing on the roof. Also, in the traditional Inuit igloo the heat from the kulliq (stone lamp) causes the interior to melt slightly. This melting and refreezing builds up an ice sheet and contributes to the strength of the igloo.[6]

The sleeping platform is a raised area compared to where one enters the igloo. Because warmer air rises and cooler air settles, the entrance area will act as a cold trap whereas the sleeping area will hold whatever heat is generated by a stove, lamp or body heat.

Use

There are three types of igloo, all of different sizes and all are used for different purposes. Although the most recognizable type of dwelling of the Inuit, the igloo was not the only type; nor was it used at all times.

The smallest of all iglooit was constructed as a temporary shelter. Hunters while out on the land or sea ice camped in one of these iglooit for one or two nights.

Next in size was the semi-permanent, intermediate sized family dwelling. This usually was a single room dwelling that housed one or two families. Often there were several of these in a small area, which formed an "Inuit village."

The largest of the igloos was normally built in groups of two. One of the buildings was a temporary building constructed for special occasions; the other was built near by for living. This was constructed either by enlarging a smaller igloo or building from scratch. These could have up to five rooms and housed up to 20 people. A large igloo may have been constructed from several smaller igloos attached by their tunnels giving a common access to the outside. These were used to hold community feasts and traditional dances.

Variations

Traditional types

There were three traditional types of igloos, all of different sizes and all used for different purposes.

The smallest was constructed as a temporary shelter, usually only used for one or two nights. These were built and used during hunting trips, often on open sea ice.

Next in size was the semi-permanent, intermediate-sized family dwelling. This was usually a single room dwelling that housed one or two families. Often there were several of these in a small area, which formed an "Inuit village".

The largest of the igloos was normally built in groups of two. One of the buildings was a temporary structure built for special occasions, the other built nearby for living. These might have had up to five rooms and housed up to 20 people. A large igloo might have been constructed from several smaller igloos attached by their tunnels, giving common access to the outside. These were used to hold community feasts and traditional dances.

The 1922 documentary Nanook of the North contains the oldest surviving movie footage of an Inuit constructing an igloo. In the film, Nanook (real name Allakariallak) builds a large family igloo as well as a smaller igloo for sled pups. Nanook demonstrates the use of an ivory knife to cut and trim snow block, as well as the use of clear ice for a window. His igloo was built in about one hour, and was large enough for five people. The igloo was cross-sectioned for filmmaking, so interior shots could be made.

Modifications

The Central Inuit, especially those around the Davis Strait, lined the living area with skin, which could increase the temperature within from around 2 °C (36 °F) to 10-20 °C (50-68 °F).

Quinzhee

Uses

For fun, or for winter camping and survival purposes, it is possible to construct a snow shelter by gathering a large pile of snow and excavating the inside.

Differences between a quinzhee and an igloo

The snow for a quinzhee need not be of the same quality as required for an igloo. Quinzhees are not usually meant as a form of permanent shelter, while igloos can be used for seasonal and year round habitation. The construction of a quinzhee is slightly easier than the construction of an igloo, although the overall result is somewhat less sturdy and more prone to collapsing in harsh weather conditions. Quinzhees are normally constructed in times of necessity, usually as an instrument of survival, so aesthetic and long-term dwelling considerations are normally exchanged for economy of time and materials.

Construction

To begin one must locate a relatively flat area where snow is in abundance. It is important to use snow that hasn't been piled naturally. If your snowpile is natural (i.e. a snow drift), break it up first. This is done to prevent a situation where there are two different levels of setness, which can cause collapse during excavations. One must then pile snow to its desired height (typically 6 - 10 feet) and leave it for a length of time to harden. It is worth noting that a small quinzhee is more desirable than a larger one as all of the heat within them rises to the top. In other words, a smaller quinzhee affords a warmer living environment than a larger one typically would. Quinzhees are not typically built so one can stand in them. The resident should be able to comfortably sit up inside while perhaps being able to crouch. One should also attempt to make a pile of snow in front of the quinzhee about four feet in length which will serve as a tunnel to gain access to the structure. After piling the snow the site should be left for up to several hours while the snow sets, making excavation possible. Before excavating one can put sticks in the roof and wall, approximately 10 in (25 cm) deep, to be used as a guide when digging out the interior. After this is completed one digs until the sticks are reached.

Dangers

People climbing on the house are the primary reason why quinzhees collapse. A collapsing quinzhee can be very dangerous if someone gets caught inside. Just as in an avalanche, the weight of the snow often makes it impossible to dig oneself free. Suffocation may occur if the occupants are not rescued quickly enough. In addition to this, many quinzhees collapse during their construction for a variety of reasons, including poor snow conditions, warm weather or failure to let the snow set long enough. To protect oneself against collapse during construction, one should only ever dig a qunizhee while on one's knees, never one's back. In the event of collapse, one stands a much better chance at digging oneself out if one is on one's knees.

A quinzhee should only be constructed alone if in a survival situation.

In popular use

In heraldry, the igloo appears as the crest in the coat of arms of Nunavut.

Notes

- ↑ Charles D. Arnold and Elisa J. Hart, "The Mackenzie Inuit Winter House," Arctic 45(2) (June 1992): 199-200. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Richard M. Levy, Peter C. Dawson, and Charles Arnold, "Reconstructing traditional Inuit house forms using three-dimensional interactive computer modelling," Visual Studies 19(1) (2004): 26-35. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Igloo," Asuilaak Living Dictionary. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Rich Holihan, Dan Keeley, Daniel Lee, Powen Tu and Eric Yang How Warm is an Igloo?, BEE453 Spring 2003. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Allen O'Bannon and Mike McClelland, Allen & Mike's Really Cool Backcountry Ski Book: Traveling and Camping Skills for a Winter Environment, (Chockstone Press, 1996, ISBN 1575400766), 80-86.

- ↑ What house-builders can learn from igloos, 2008, Dan Cruickshank, BBC

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hoyt, Alia. How Igloos Work. HowStuffWorks.com, January 17, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- O'Bannon, Allen, and Mike McClelland. Allen & Mike's Really Cool Backcountry Ski Book: Traveling and Camping Skills for a Winter Environment. Chockstone Press, 1996. ISBN 1575400766

- Weiss, Harvey. Shelters, from Teepee to Igloo. Ty Crowell Co, 1988. ISBN 0690045530

- Yankielun, Norbert E. How to Build an Igloo: And Other Snow Shelters. W. W. Norton, 2007. ISBN 0393732150

External links

- How to Build Winter Shelters and Survive

- Picture of a Quinzhee

- My Quinzhee Camping Page

- How to make a Snow Mound Shelter

- Quinzhee Hut Building

- Igloo — the Traditional Arctic Snow Dome

- How to Build an Igloo

- Fun Family Crafts - - Build an Igloo or Snow House

- How Igloos Work at HowStuffWorks

- Watch How to Build an Igloo

- Building an Igloo by Hugh McManners

- Field Manual for the U.S. Antarctic Program Chapter 11 Snow Shelters pp140-145

- Traditional Dwellings: Igloos (1) (Interview on igloos)

- An article on igloos from The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Nanook of the North: video from the 1922 film showing Nanook and Nyla building an igloo.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.