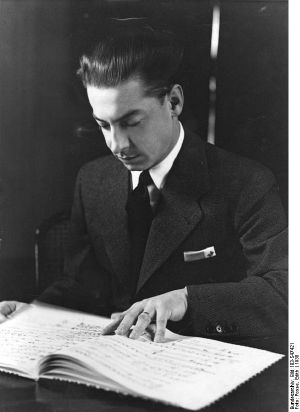

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (5 April 1908–16 July 1989) was an Austrian orchestra and opera conductor, one of the most renowned twentieth-century conductors. His obituary in The New York Times described him as "probably the world's best-known conductor and one of the most powerful figures in classical music."[1] Karajan held the position of music director of the Berlin Philharmonic for 35 years and made numerous audio and video recordings with that ensemble. Along with classical recording mogul, Walter Legge, he played an important role in bringing credibility to London's Philharmonia Orchestra in the 1950s. He is the top-selling classical music recording artist of all time with an estimated at 200 million records sold.[2] He was one of the first international classical musicians to understand the importance of the recording industry and eventually established his own video production company, Telemondial.

Biography

Early years

Karajan was born in Salzburg, Austria as Heribert Ritter von Karajan.[3] He was the son of an upper-bourgeois Salzburg family and was a child prodigy at the piano.[4] From 1916 to 1926, he studied at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, where he eventually became interested in conducting.

In 1929, he conducted Richard Strauss' opera Salome at the Festspielhaus in Salzburg, and from 1929 to 1934, Karajan served as first Kapellmeister at the Stadttheater in Ulm. In 1933, Karajan made his conducting debut at the Salzburg Festival with the Walpurgisnacht Scene in Max Reinhardt's production of Faust. The following year, and again in Salzburg, Karajan led the Vienna Philharmonic for the first time, and from 1934 to 1941, Karajan also conducted opera and symphony concerts at the Aachen opera house.

In 1935, Karajan's career was given a significant boost when he was appointed Germany's youngest Generalmusikdirektor and was a guest conductor in Bucharest, Brussels, Stockholm, Amsterdam, and Paris [1] [5]. Moreover, in 1937, Karajan made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Berlin State Opera with Beethoven's Fidelio. He enjoyed a major success in the State Opera with Tristan und Isolde and in 1938, his performance of the opera was hailed by a Berlin critic as Das Wunder Karajan (The Karajan miracle), claiming that his "success with Wagner's demanding work Tristan und Isolde sets himself alongside Furtwängler and de Sabata, the greatest opera conductors in Germany at the present time".[6]

Receiving a contract with Europe's premiere recoding company, Deutsche Grammophon that same year, Karajan made the first of numerous recordings by conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin in Mozart's overture to Die Zauberflöte.

Adolf Hitler did not appreciate Karajan's 1939 performance of Wagner's Die Meistersinger according to Winifred Wagner, because Karajan, who was conducting without a score, lost his way due to a memory slip, causing the singers to be confused, the performance halted and the curtain rung down in confusion. According to Winifred Wagner, Hitler decided that Karajan was never to conduct at the annual Bayreuth festival. However, as a favorite of Hermann Göring he would continue his work as conductor of the Staatskapelle (1941-1945), the orchestra of the Berlin State Opera, where he would accompany about 150 opera performances in total.

On 22 October 1942, at the height of the war, Karajan married his second wife, Anna Maria "Anita" Sauest, née Gütermann, the daughter of a well-known sewing machine magnate, and who, having a Jewish grandfather, was considered Vierteljüdin (one-quarter Jewish). By 1944, Karajan was, by his own account, losing favor with the Nazi leaders, but he still conducted concerts in wartime Berlin on 18 February 1945, and fled Germany with Anita for Milan a short time later.[7] Karajan and Anita divorced in 1958.

In the closing stages of the war, Karajan relocated his family to Italy with the assistance of Victor de Sabata.[8]Karajan was discharged by the Austrian denazification examining board on 18 March 1946, and resumed his conducting career shortly thereafter.[9]

Postwar years

In 1946, Karajan gave his first post-war concert, in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic, but he was banned from further conducting activities by the Soviet occupation authorities because of his Nazi party membership. That summer, he participated anonymously in the Salzburg Festival. The following year, he was allowed to resume conducting.

In 1949, Karajan became artistic director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna. He also conducted at La Scala in Milan. However, his most prominent activity at this time was recording with the newly-formed Philharmonia Orchestra in London, helping to establish the ensemble into one of the world's finest. It was also in 1949 that Karajan began his lifetime long association with the Lucerne Festival[10].In 1951 and 1952, he was invited conducted at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

In 1955, he was appointed music director for life of the Berlin Philharmonic as successor to the legendary Wilhelm Furtwängler. From 1957 to 1964, he was artistic director of the Vienna State Opera. He was closely involved with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Salzburg Festival, where he initiated the Easter Festival, which would remain tied to the Berlin Philharmonic's Music Director after his tenure. He continued to perform, conduct and record prolifically until his death in Anif in 1989, primarily with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Berlin Philharmonic.

Nazi membership

Karajan joined the Nazi Party in Salzburg on 8 April 1933; his membership number was 1.607.525. In June the Nazi Party was outlawed by the Austrian government. However, Karajan's membership was valid until 1939. In this year the former Austrian members were verified by the general office of the Nazi Party. Karajan's membership was declared invalid, but his accession to the party was retroactively determined to have been on May 1, 1933 in Ulm, with membership number 3,430,914. [11] [12]

Karajan's membership in the Nazi Party and increasingly prominent career in Germany from 1933 to 1945 cast him in an uncomplimentary light after the war. While Karajan's defenders have argued that he joined the Nazis only to advance his own career, critics such as [[Jim Svejda] have pointed out that other prominent conductors, such as Bruno Walter, Erich Kleiber and Arturo Toscanini, fled from fascist Europe at the time. However, British music critic Richard Osborne argues that among the many well-known conductors who worked in Germany throughout the war years—a list that includes Wilhelm Furtwängler, Ernest Ansermet, Carl Schuricht, Karl Böhm, Hans Knappertsbusch, Clemens Krauss and Karl Elmendorff—Karajan was in fact one of the youngest and least advanced in his career.[13]

Some have argued that careerism could not have been Karajan's sole motivation, since he first joined the Nazi Party in 1933 in Salzburg, Austria, five years before the Anschluss. [14] In The Cultural Cold War, published in Britain as Who Paid the Piper?, Frances Stonor Saunders noted that Karajan "had been a party member since 1933, and opened his concerts with the Nazi favourite 'Horst Wessel Lied.'" In addition, although he did open a Paris concert with the Horst Wessel Lied, he had a history of avoiding political or nationalistic gestures at performances wherever possible.

Jewish musicians such as Isaac Stern, Arthur Rubinstein, and Itzhak Perlman refused to play in concerts with Karajan because of his Nazi past. Richard Tucker also pulled out from a 1956 recording of Il trovatore when he learned that Karajan would be conducting, and threatened to do the same on the Maria Callas recording of Aida, until Tullio Serafin replaced Karajan. There has been speculation as to whether Karajan was committed to the Nazi cause given his marriage in 1942 to Anita Gütermann, who was partly of Jewish origin. Evidence suggests that he received several threats to his career as a result of the engagement, and had attempted to resign from the Nazi Party when questioned about it.

Commentators such as Osborne and the British journalist Mark Lawson[15] have suggested that music, and access to making music, over-rode everything for Karajan, and that may have led to him making amoral decisions such as Nazi membership in order to get what he wanted with regard his conducting aspirations. Lawson in particular has suggested that the lack of conclusive evidence about Karajan's personal political ideology, and apparently contradictory episodes in his life (such as his marriage), at least suggests that his membership was more a means to an end than the expression of an ideological standpoint. However, the debate continues to this day.

Musicianship and Style

There is widespread agreement that Karajan possessed a special gift for extracting beautiful sounds from an orchestra. Opinion varies concerning the greater aesthetic ends to which The Karajan Sound was applied. Some critics felt the highly polished and "creamy" sounds that became his trademark sound, did not work in certain repertory, such as the classical symphonies of Mozart and Haydn and contemporary works by Stravinsky and Bartok. However, it has been argued by commentator Jim Svejda and others that Karajan's pre-1970 manner did not sound polished as it is later alleged to have become.

Two reviews from the Penguin Guide to Compact Discs can be quoted to illustrate the point.

- Concerning a recording of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde, a canonical Romantic work, the Penguin authors wrote "Karajan's is a sensual performance of Wagner's masterpiece, caressingly beautiful and with superbly refined playing from the Berlin Philharmonic" and it is listed in first place on pages 1586-7 of the 1999 Penguin Guide to Compact Discs; 2005, p1477.

- About Karajan's recording of Haydn's "Paris" symphonies, the same authors wrote, "big-band Haydn with a vengeance ... It goes without saying that the quality of the orchestral playing is superb. However, these are heavy-handed accounts, closer to Imperial Berlin than to Paris ... the Minuets are very slow indeed ... These performances are too charmless and wanting in grace to be whole-heartedly recommended."[16]

The same Penguin Guide does nevertheless give the highest compliments to Karajan's recordings of the selfsame Haydn's two oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons.[17]

Regarding twentieth century music, Karajan had a strong preference for conducting and recording pre-1945 works (Mahler, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, Bartók, Sibelius, Richard Strauss, Puccini, Ildebrando Pizzetti, Arthur Honegger, Prokofiev, Debussy, Ravel, Paul Hindemith, Carl Nielsen and Stravinsky), but also did record Shostakovich's Symphony No. 10 (1953) twice, and did premiere Carl Orff's "De Temporum Fine Comoedia" in 1973.

Karajan and Recording Technology

Karajan was one of the first international figures to understand the importance of the recording industry. He always invested into the latest state-of-the-art sound systems and made concerted efforts to market and protect the ownership of his recordings. This eventually led to the creation of his own production company (Telemondial) to record, duplicate and market his recorded legacy.

He also played an important role in the development of the original compact disc digital audio format. He championed this new consumer playback technology, lent his prestige to it, and appeared at the first press conference announcing the format. The maximum playing time of CD prototypes was sixty minutes, but the final specification enlarged the disc size and extended the capacity to seventy-four minutes. There is a story that this was due to Karajan's insistence that the format have sufficient capacity to contain Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on a single disc. Though widely reported,Snopes says the veracity of this claim is unverifiable. [18].

What is undeniable is that SONY president Norio Ohga and chairman, Akio Morita greatly admired Karajan and sought to use his influence in marketing CD technology to the world. Karajan would eventually sign a contract with SONY to be the distributor of videos of his final concerts on the DVD format.

In popular culture

- Herbert von Karajan was recently selected as a main motif for a high value collectors' coin: the 100th Birthday of Herbert von Karajan commemorative coin. The nine-sided silver coin, in the reverse, shows Karajan in one of his typically dynamic poses while conducting. In the background is the score of Beethoven's Ninth.

- Karajan's recording of Johann Strauss An der schönen, blauen Donau (The Blue Danube waltz) was used by director Stanley Kubrick in his science-fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey (with Kubrick animating the sequence to match the prerecorded music, the opposite of the usual practice for soundtracks). The popular effect of this unconventional use of the music was such that the music became more identified for subsequent generations with space stations, primitive men, alien artifacts and such, than with the original waltz. Some years later, Kubrick again used Karajan's recordings, this time Béla Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta in The Shining. Although there is a 1958 version by Ferenc Fricsay of the second movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film A Clockwork Orange, the symphony's finale we hear at the end of the movie is Karajan's now-famous 1963 recording. These two versions are from DG and performed by the same orchestra, The Berlin Philharmonic.

Discography

A complete discography of Karajan's recordings is available at the website of the Herbert von Karajan Centrum.

See also

- Berlin State Opera

- Raffaello de Banfield

Notes

- ↑ John Rockwell. "Herbert von Karajan Is Dead; Musical Perfectionist was 81", The New York Times, 17 July 1989, pp. p. A1.

- ↑ The Life and Death of Classical Music by Norman Lebrecht, p. 137.

- ↑ Osborne (1987)

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Article for Herbert von Karajan

- ↑ The woman in the footage is Winifred Wagner, a lifetime friend of Adolf Hitler

- ↑ Osborne, (2000), p. 114]

- ↑ Osborne (2000).

- ↑ Andrews, Deborah. The Annual Obituary, St James Press, 1990. ISBN 1558620567, pp. 417.

- ↑ Osborne (2000); Karajan's deposition is presented in whole as Appendix C.

- ↑ Lucerne Festival homepage, Karajan Celebration 2008

- ↑ Fred K. Prieberg: Handbuch Deutsche Musiker 1933–1945 Kiel, 2004, CD-ROM-Lexicon, p. 3545f. The author inspected the files of Karajan (as part of the Reichskulturkammer) at the Bundesarchiv in Berlin (former Berlin Document Center). This background story was first published by Paul Moor in: High Fidelity Vol. 7/10 October 1957, p. 52-55, 190, 192-194 (The Operator). In addition, Prieberg's opinion about the Karajan biographer Richard Osborne has been stated: "his knowledge of history is sadly very low" (p. 3575)

- ↑ Karsten Kammholz (not quite with the accuracy of Prieberg: Der Mann, der zweimal in die NSDAP eintrat; in: Die Welt, January 26, 2008

- ↑ Osborne (2000), p. 85

- ↑ http://www.classicalnotes.net/features/furtwangler.html

- ↑ BBC Radio 4 broadcast

- ↑ [these recordings are no longer mentioned in the 1999 edition of the Penguin Guide to Compact Discs.]

- ↑ [The Creation is listed first on pp. 656-7 of the 1999 Penguin Guide to Compact Discs, and the comment reads: "Among Versions of The Creation sung in German, Karajan's 1969 set remains unsurpassed, and now reissued as one of DG's 'Originals' at mid-price, is a clear first choice despite two small cuts..."] [The Seasons is, by 1999, listed in the Penguin Guide to Compact Discs in third place on p. 661, and the text states "Karajan's 1973 recording of The Seasons offers a fine, polished performance which is often very dramatic too. The characterizations is strong ... the remastered sound is drier than the original but is vividly wide. etc. etc. ..."]

- ↑ Roll Over, Beethoven, 5.23.2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lebrecht, Norman (2001). The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit of Power. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 0806520884.

- Lebrecht, Norman (2007). The Life and Death of Classical Music. New York: Anchor Books,. ISBN 9781400096589.

- Layton, Robert and Greenfield, Edward; March, Ivan (1996). Penguin Guide to Compact Discs. London; New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140513671.

- Monsaingeon, Bruno (2001). Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0571205534.

- Osborne, Richard (1998). Herbert von Karajan. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701167149.

- Osborne, Richard (2000). Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1555534252.

- Raymond, Holden (2005). The Virtuoso Conductors. New Haven, Connecticut; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300093268.

- Alessandro, Zignani (2008). Herbert von Karajan. Il Musico perpetuo. Varese: Zecchini Editore,. ISBN 8887203679.

External links

- Official Herbert von Karajan website, Vienna

- 1963 Stereo Review interview

- Tribute site to Herbert von Karajan

- Obituary by the New York Times

- An obituary essay by James Wierzbicki

- A range of opinions from readers of Gramophone magazine

Video

- Karajan conducting Beethoven's Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21

- Karajan conducting Beethoven's Symphony No. 2

- Karajan conducting Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 'Eroica' - Part 1

- Karajan conducting Beethoven's 5th Symphony, rare old 1966 video

- Karajan conducting Beethoven's 9th Symphony (P1)

- Karajan conducting Beethoven's 9th Symphony (P2)

- Karajan cunducting Verdi's Requiem: Dies Irae

| Preceded by: Clemens Krauss |

Music Director, Berlin State Opera 1939–1945 |

Succeeded by: Joseph Keilberth |

| |||||

Template:Berliner Philharmoniker conductors

| |||||

| |||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Karajan, Herbert von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Karajan, Heribert Ritter von |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Austrian orchestra and opera conductor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 5 April 1908 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Salzburg, Austria |

| DATE OF DEATH | 16 July 1989 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Anif, Austria |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.