Karajan, Herbert von

Dave Eaton (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (38 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} | ||

| + | {{epname|Karajan, Herbert von}} | ||

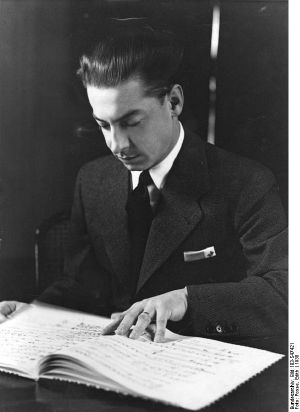

[[Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-S47421, Herbert von Karajan.jpg|thumb|Herbert von Karajan]] | [[Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-S47421, Herbert von Karajan.jpg|thumb|Herbert von Karajan]] | ||

| − | '''Herbert von Karajan''' (5 | + | '''Herbert von Karajan''' (April 5, 1908 - July 16, 1989) was an [[Austria]]n [[orchestra]] and [[opera]] [[conducting|conductor]], one of the most renowned twentieth century conductors, and a major contributor to the advancement of classical [[music]] recordings. |

| + | |||

| + | Karajan held the position of music director of the [[Berlin Philharmonic]] for 35 years and made numerous audio and video recordings with that ensemble. Although his [[Nazi]] past resulted in his being shunned by prominent [[Jewish]] [[musician]]s, his career in European music capitals was nevertheless one of the most successful in the annals of twentieth century [[classical music]]. He also played an important role bringing credibility to London's [[Philharmonia Orchestra]] in the 1950s. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Karajan is the top-selling classical music recording artist of all time, with an estimated 200 million records sold. He was one of the first international classical [[musician]]s to understand the importance of the [[recording industry]] and eventually established his own video production company, Telemondial. Along with American [[composer]]/conductor, [[Leonard Bernstein]], Karajan is probably the most recognized name among [[conductor]]s of the twentieth century. | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

===Early years=== | ===Early years=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-R92291, Herbert von Karajan und Germaine Lubin.jpg|thumb|Karajan with French [[soprano]] [[Germaine Lubin]] in 1941.]] | ||

| − | Karajan was born in [[Salzburg]], Austria | + | Karajan was born in [[Salzburg]], Austria, the son of an upper-bourgeois Salzburg family. A child prodigy at the [[piano]], he studied at the [[Mozarteum]] in Salzburg from 1916 to 1926, where he eventually became interested in conducting. |

| − | In 1929, | + | In 1929, Karajan conducted [[Richard Strauss]]' [[opera]] ''[[Salome (opera)|Salome]]'' at the [[Festspielhaus]] in Salzburg, and from 1929 to 1934, he served as first [[Kapellmeister]] at the Stadttheater in [[Ulm]]. In 1933, he conducted for the first time at the prestigious [[Salzburg Festival]] in [[Max Reinhardt (theatre director)|Max Reinhardt]]'s production of ''[[Faust (opera)|Faust]]''. The following year, again in Salzburg, Karajan led the [[Vienna Philharmonic]]. |

| − | In 1935, Karajan's career was given a significant boost when he | + | In 1935, Karajan's career was given a significant boost when he was appointed Germany's youngest ''Generalmusikdirektor'' and was a guest conductor in [[Bucharest]], [[Brussels]], [[Stockholm]], [[Amsterdam]], and [[Paris]]. From 1934 to 1941 he also conducted [[opera]] and [[symphony]] concerts at the [[Aachen]] opera house. In 1937, Karajan made his debut with the [[Berlin Philharmonic]] and the [[Berlin State Opera]] with [[Beethoven]]'s ''[[Fidelio]]''. He enjoyed a major success in the State Opera with ''[[Tristan und Isolde]]'' in 1938. The performance was hailed as "the Karajan miracle," and led to comparisons with Germany's most famous conductors. Receiving a contract with Europe's premiere recoding company, [[Deutsche Grammophon]] that same year, Karajan made the first of numerous recordings by conducting the [[Staatskapelle Berlin]] in [[Mozart]]'s overture to ''[[Die Zauberflöte]]''. |

| − | + | [[Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-R92264, Herbert von Karajan.jpg|left|250px|thumb|Karajan conducts in [[Berlin]] during WWII.]] | |

| − | + | Karajan suffered a major embarrassment during a 1939 performance of [[Wagner]]'s ''[[Die Meistersinger]],'' which he conducted without a score. As a result of a memory slip, he lost his way, causing the singers to become confused. The performance halted and the curtain was brought down. As a result of this error, [[Adolf Hitler]] decided that Karajan was never to conduct at the annual [[Bayreuth Festival]] of Wagnerian works. However, as a favorite of [[Hermann Göring]], Karajan continued his work as [[conductor]] of the Staatskapelle (1941-1945), the [[orchestra]] of the [[Berlin State Opera]], where he would conduct about 150 [[opera]] performances in total. | |

| − | + | In October 1942, at the height of the war, Karajan married his second wife, the daughter of a well-known sewing machine magnate, Anna Maria "Anita" Sauest, née Gütermann, who had a [[Jewish]] grandfather. By 1944, Karajan, a [[Nazi]] party member, was losing favor with the Nazi leaders. However, he still conducted concerts in wartime Berlin as late as February 1945. In the closing stages of the war, Karajan relocated his family to [[Italy]] with the assistance of Italian conductor [[Victor de Sabata]]. | |

| − | + | ==Nazi controversy== | |

| + | Like many musicians in [[Germany]], the period from 1933 to 1946 was especially vexatious. Few in the early part of [[Hitler]]'s rise to power envisioned the atrocities that were to be perpetrated in the name of the [[Nazi]] [[ideology]]. Certain musicians looked at joining the party as a gesture of national pride. Others viewed it as a stepping stone to higher positions and opportunities for better employment. Though some prominent musicians (conductor [[Karl Bohm]], for example) were unapologetic in the their Nazi affiliations, some remained agnostic ([[Wilhelm Furtwangler]]), and others fled Germany (such as composer [[Paul Hindemith]]) out of fear of retribution for their criticism of Nazi ideas. | ||

| − | + | Karajan's case is particularly interesting due to the fact that there exists two records of his joining the party. If the later of the two enrollments was correct, it gives rise to the notion that he joined the party knowing of Hitler's intentions and chose to join for career advancement. This was a charge levied at many German musicians in the post-war era. However there has been little evidence and/or testimonies by those who knew him in the Nazi years to support any claims that he was an active collaborator in the Nazi machine beyond careerism. Still, the stigma of his being a Nazi sympathizer remained a part of his musical life. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Postwar career=== | |

| + | [[Image:ItzhakPerlmanWhitehouse2.jpg|thumb|Jewish musicians such as [[Itzhak Perlman]] refused to play with Krajan because of his [[Nazi]] past.]] | ||

| + | Karajan was discharged by the Austrian de-Nazification examining board on March 18, 1946, and resumed his conducting career shortly thereafter. | ||

| + | He soon gave his first post-war concert with the Vienna Philharmonic. However, he was banned from further conducting activities by the Soviet occupation authorities because of his [[Nazi]] party membership. That summer, he participated anonymously in the [[Salzburg Festival]]. The following year, he was allowed to resume conducting. | ||

| − | + | Jewish musicians such as [[Isaac Stern]], [[Arthur Rubinstein]], and [[Itzhak Perlman]] refused to play in concerts with Karajan because of his Nazi past. Tenor [[Richard Tucker]] pulled out from a 1956 recording of ''[[Il trovatore]]'' when he learned that Karajan would be conducting, and threatened to do the same on the [[Maria Callas]] recording of ''[[Aida]],'' until Karajan was replaced by [[Tullio Serafin]]. | |

| − | + | In 1949, Karajan became artistic director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, (Society of Music Friends) in Vienna. He also conducted at [[La Scala]] in Milan. However, his most prominent activity at this time was recording with the newly-formed [[Philharmonia Orchestra]] in [[London]], helping to establish the ensemble into one of the world's finest. It was also in 1949 that Karajan began his lifetime long association with the [[Lucerne Festival]]. In 1951 and 1952, he was once again invited to conduct at the [[Bayreuth Festival]]. | |

| − | Karajan | ||

| − | Karajan | + | In 1955, Karajan was appointed [[music director]] for life of the [[Berlin Philharmonic]] as successor to the legendary [[Wilhelm Furtwängler]]. From 1957 to 1964, he was artistic director of the [[Vienna State Opera]]. He was closely involved with the [[Vienna Philharmonic]] and the [[Salzburg Festival]], where he initiated the annual Easter Festival. He continued to perform, conduct and record prolifically, primarily with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Berlin Philharmonic until his death in [[Anif]] in 1989. In 1989, on one of his final American appearances in [[New York City]], Jewish demonstrators protested his appearance at [[Carnegie Hall]]. |

| − | + | Karjan recorded the nine symphonies of [[Beethoven]] on four different occasions during his lifetime. His 1963 accounts with the Berlin Philharmonic remain among the highest selling sets of these seminal works. | |

| − | + | ==Musicianship and style== | |

| + | There is widespread agreement that Karajan possessed a special gift for extracting beautiful sounds from an orchestra. Opinion varies concerning the greater aesthetic ends to which ''The Karajan Sound'' was applied. Some critics felt the highly polished and "creamy" sounds that became his trademark did not work in certain repertory, such as the classical symphonies of [[Mozart]] and [[Haydn]] and contemporary works by [[Stravinsky]] and [[Bartok]]. However, it has been argued that Karajan's pre-1970 style did not sound as polished is indicated in his later performances and recordings. | ||

| − | + | Regarding [[contemporary music|twentieth century]] music, Karajan had a strong preference for conducting and recording pre-1945 works (such as those by [[Gustav Mahler|Mahler]], [[Arnold Schoenberg|Schoenberg]], [[Alban Berg|Berg]], [[Anton Webern|Webern]], [[Béla Bartók|Bartók]], [[Jean Sibelius|Sibelius]], [[Richard Strauss]], [[Giacomo Puccini|Puccini]], [[Ildebrando Pizzetti]], [[Arthur Honegger]], [[Sergei Prokofiev|Prokofiev]], [[Claude Debussy|Debussy]], [[Ravel]], [[Paul Hindemith]], [[Carl Nielsen]], and [[Igor Stravinsky|Stravinsky]]), but also recorded [[Dmitri Shostakovich|Shostakovich's]] ''Symphony No. 10'' (1953) twice, and premiered [[Carl Orff]]'s "De Temporum Fine Comoedia" in 1973. | |

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | + | [[Image:CD autolev crop.jpg|thumb|200px|Karajan was instrumental in the development of the [[compact disc]].]] | |

| + | Karajan was one of the first international figures to understand the importance of the recording industry. He always invested in the latest state-of-the-art sound systems and made concerted efforts to market and protect the ownership of his recordings. This eventually led to the creation of his own production company (Telemondial) to record, duplicate and market his recorded legacy. | ||

| − | + | He also played an important role in the development of the original [[compact disc]] digital audio format. He championed this new consumer playback technology, lent his prestige to it, and appeared at the first press conference announcing the format. It was widely reported, though unverified, that the expansion of the CD's prototype format of 60 minutes to its final specification of 74 minutes was due to Karajan's insistence that the format have sufficient capacity to contain Beethoven's [[Symphony No. 9 (Beethoven)|Ninth Symphony]] on a single disc. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | He also played an important role in the development of the original [[compact disc]] digital audio format. He championed this new consumer playback technology, lent his prestige to it, and appeared at the first press conference announcing the format. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The controversy surrounding his affiliation with [[Adolf Hitler]] and the [[Nazi]]s not withstanding, Herbert von Karajan was undoubtedly the most prominent conductor in Europe in that later half of the twentieth century. | ||

| + | Karajan was the recipient of many honors and awards. On June 21, 1978, he received the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from [[Oxford University]]. He was honored by the "Médaille de Vermeil" in Paris, the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in London, the Olympia Award of the Onassis Foundation in Athens and the [[UNESCO]] International Music Prize. He received two Gramophone awards for recordings of Mahler's Ninth Symphony and the complete ''[[Parsifal]]'' recordings in 1981. In 2002, the [[Herbert von Karajan Music Prize]] was founded in his honor. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Conductor (music)|Conductor]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * Alessandro, Zignani. ''Herbert von Karajan. Il Musico perpetuo.'' Varese: Zecchini Editore, 2008. ISBN 8887203679. |

| − | * | + | * Layton, Robert, Edward Greenfield, and Ivan March. ''Penguin Guide to Compact Discs.'' New York: Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 0140513671. |

| − | * | + | * Lebrecht, Norman. ''The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit of Power.'' New York: Citadel Press, 2001. ISBN 0806520884. |

| − | + | * —. ''The Life and Death of Classical Music.'' New York: Anchor Books, 2007. ISBN 9781400096589. | |

| − | * | + | * Monsaingeon, Bruno. ''Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations.'' Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 0571205534. |

| − | * | + | * Osborne, Richard. ''Herbert von Karajan.'' London: Chatto & Windus, 1998. ISBN 0701167149. |

| − | * | + | * —. ''Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music.'' Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000. ISBN 1555534252. |

| − | + | * Raymond, Holden. ''The Virtuoso Conductors.'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300093268. | |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http:// | + | All links retrieved December 20, 2017. |

| + | *[http://karajan.org/jart/prj3/karajan/main.jart?reserve-mode=active&rel=en Official Karajan website] | ||

*[http://www.overgrownpath.com/2008/09/karajan-on-boulez-stockhausen-and.html 1963 Stereo Review interview] | *[http://www.overgrownpath.com/2008/09/karajan-on-boulez-stockhausen-and.html 1963 Stereo Review interview] | ||

*[http://www.karajan.co.uk/index.html Tribute site to Herbert von Karajan] | *[http://www.karajan.co.uk/index.html Tribute site to Herbert von Karajan] | ||

*[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DE3DD173BF934A25754C0A96F948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1 Obituary by the New York Times] | *[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DE3DD173BF934A25754C0A96F948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1 Obituary by the New York Times] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 15:16, 20 December 2017

Herbert von Karajan (April 5, 1908 - July 16, 1989) was an Austrian orchestra and opera conductor, one of the most renowned twentieth century conductors, and a major contributor to the advancement of classical music recordings.

Karajan held the position of music director of the Berlin Philharmonic for 35 years and made numerous audio and video recordings with that ensemble. Although his Nazi past resulted in his being shunned by prominent Jewish musicians, his career in European music capitals was nevertheless one of the most successful in the annals of twentieth century classical music. He also played an important role bringing credibility to London's Philharmonia Orchestra in the 1950s.

Karajan is the top-selling classical music recording artist of all time, with an estimated 200 million records sold. He was one of the first international classical musicians to understand the importance of the recording industry and eventually established his own video production company, Telemondial. Along with American composer/conductor, Leonard Bernstein, Karajan is probably the most recognized name among conductors of the twentieth century.

Biography

Early years

Karajan was born in Salzburg, Austria, the son of an upper-bourgeois Salzburg family. A child prodigy at the piano, he studied at the Mozarteum in Salzburg from 1916 to 1926, where he eventually became interested in conducting.

In 1929, Karajan conducted Richard Strauss' opera Salome at the Festspielhaus in Salzburg, and from 1929 to 1934, he served as first Kapellmeister at the Stadttheater in Ulm. In 1933, he conducted for the first time at the prestigious Salzburg Festival in Max Reinhardt's production of Faust. The following year, again in Salzburg, Karajan led the Vienna Philharmonic.

In 1935, Karajan's career was given a significant boost when he was appointed Germany's youngest Generalmusikdirektor and was a guest conductor in Bucharest, Brussels, Stockholm, Amsterdam, and Paris. From 1934 to 1941 he also conducted opera and symphony concerts at the Aachen opera house. In 1937, Karajan made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Berlin State Opera with Beethoven's Fidelio. He enjoyed a major success in the State Opera with Tristan und Isolde in 1938. The performance was hailed as "the Karajan miracle," and led to comparisons with Germany's most famous conductors. Receiving a contract with Europe's premiere recoding company, Deutsche Grammophon that same year, Karajan made the first of numerous recordings by conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin in Mozart's overture to Die Zauberflöte.

Karajan suffered a major embarrassment during a 1939 performance of Wagner's Die Meistersinger, which he conducted without a score. As a result of a memory slip, he lost his way, causing the singers to become confused. The performance halted and the curtain was brought down. As a result of this error, Adolf Hitler decided that Karajan was never to conduct at the annual Bayreuth Festival of Wagnerian works. However, as a favorite of Hermann Göring, Karajan continued his work as conductor of the Staatskapelle (1941-1945), the orchestra of the Berlin State Opera, where he would conduct about 150 opera performances in total.

In October 1942, at the height of the war, Karajan married his second wife, the daughter of a well-known sewing machine magnate, Anna Maria "Anita" Sauest, née Gütermann, who had a Jewish grandfather. By 1944, Karajan, a Nazi party member, was losing favor with the Nazi leaders. However, he still conducted concerts in wartime Berlin as late as February 1945. In the closing stages of the war, Karajan relocated his family to Italy with the assistance of Italian conductor Victor de Sabata.

Nazi controversy

Like many musicians in Germany, the period from 1933 to 1946 was especially vexatious. Few in the early part of Hitler's rise to power envisioned the atrocities that were to be perpetrated in the name of the Nazi ideology. Certain musicians looked at joining the party as a gesture of national pride. Others viewed it as a stepping stone to higher positions and opportunities for better employment. Though some prominent musicians (conductor Karl Bohm, for example) were unapologetic in the their Nazi affiliations, some remained agnostic (Wilhelm Furtwangler), and others fled Germany (such as composer Paul Hindemith) out of fear of retribution for their criticism of Nazi ideas.

Karajan's case is particularly interesting due to the fact that there exists two records of his joining the party. If the later of the two enrollments was correct, it gives rise to the notion that he joined the party knowing of Hitler's intentions and chose to join for career advancement. This was a charge levied at many German musicians in the post-war era. However there has been little evidence and/or testimonies by those who knew him in the Nazi years to support any claims that he was an active collaborator in the Nazi machine beyond careerism. Still, the stigma of his being a Nazi sympathizer remained a part of his musical life.

Postwar career

Karajan was discharged by the Austrian de-Nazification examining board on March 18, 1946, and resumed his conducting career shortly thereafter. He soon gave his first post-war concert with the Vienna Philharmonic. However, he was banned from further conducting activities by the Soviet occupation authorities because of his Nazi party membership. That summer, he participated anonymously in the Salzburg Festival. The following year, he was allowed to resume conducting.

Jewish musicians such as Isaac Stern, Arthur Rubinstein, and Itzhak Perlman refused to play in concerts with Karajan because of his Nazi past. Tenor Richard Tucker pulled out from a 1956 recording of Il trovatore when he learned that Karajan would be conducting, and threatened to do the same on the Maria Callas recording of Aida, until Karajan was replaced by Tullio Serafin.

In 1949, Karajan became artistic director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, (Society of Music Friends) in Vienna. He also conducted at La Scala in Milan. However, his most prominent activity at this time was recording with the newly-formed Philharmonia Orchestra in London, helping to establish the ensemble into one of the world's finest. It was also in 1949 that Karajan began his lifetime long association with the Lucerne Festival. In 1951 and 1952, he was once again invited to conduct at the Bayreuth Festival.

In 1955, Karajan was appointed music director for life of the Berlin Philharmonic as successor to the legendary Wilhelm Furtwängler. From 1957 to 1964, he was artistic director of the Vienna State Opera. He was closely involved with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Salzburg Festival, where he initiated the annual Easter Festival. He continued to perform, conduct and record prolifically, primarily with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Berlin Philharmonic until his death in Anif in 1989. In 1989, on one of his final American appearances in New York City, Jewish demonstrators protested his appearance at Carnegie Hall.

Karjan recorded the nine symphonies of Beethoven on four different occasions during his lifetime. His 1963 accounts with the Berlin Philharmonic remain among the highest selling sets of these seminal works.

Musicianship and style

There is widespread agreement that Karajan possessed a special gift for extracting beautiful sounds from an orchestra. Opinion varies concerning the greater aesthetic ends to which The Karajan Sound was applied. Some critics felt the highly polished and "creamy" sounds that became his trademark did not work in certain repertory, such as the classical symphonies of Mozart and Haydn and contemporary works by Stravinsky and Bartok. However, it has been argued that Karajan's pre-1970 style did not sound as polished is indicated in his later performances and recordings.

Regarding twentieth century music, Karajan had a strong preference for conducting and recording pre-1945 works (such as those by Mahler, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, Bartók, Sibelius, Richard Strauss, Puccini, Ildebrando Pizzetti, Arthur Honegger, Prokofiev, Debussy, Ravel, Paul Hindemith, Carl Nielsen, and Stravinsky), but also recorded Shostakovich's Symphony No. 10 (1953) twice, and premiered Carl Orff's "De Temporum Fine Comoedia" in 1973.

Legacy

Karajan was one of the first international figures to understand the importance of the recording industry. He always invested in the latest state-of-the-art sound systems and made concerted efforts to market and protect the ownership of his recordings. This eventually led to the creation of his own production company (Telemondial) to record, duplicate and market his recorded legacy.

He also played an important role in the development of the original compact disc digital audio format. He championed this new consumer playback technology, lent his prestige to it, and appeared at the first press conference announcing the format. It was widely reported, though unverified, that the expansion of the CD's prototype format of 60 minutes to its final specification of 74 minutes was due to Karajan's insistence that the format have sufficient capacity to contain Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on a single disc.

The controversy surrounding his affiliation with Adolf Hitler and the Nazis not withstanding, Herbert von Karajan was undoubtedly the most prominent conductor in Europe in that later half of the twentieth century.

Karajan was the recipient of many honors and awards. On June 21, 1978, he received the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from Oxford University. He was honored by the "Médaille de Vermeil" in Paris, the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in London, the Olympia Award of the Onassis Foundation in Athens and the UNESCO International Music Prize. He received two Gramophone awards for recordings of Mahler's Ninth Symphony and the complete Parsifal recordings in 1981. In 2002, the Herbert von Karajan Music Prize was founded in his honor.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alessandro, Zignani. Herbert von Karajan. Il Musico perpetuo. Varese: Zecchini Editore, 2008. ISBN 8887203679.

- Layton, Robert, Edward Greenfield, and Ivan March. Penguin Guide to Compact Discs. New York: Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 0140513671.

- Lebrecht, Norman. The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit of Power. New York: Citadel Press, 2001. ISBN 0806520884.

- —. The Life and Death of Classical Music. New York: Anchor Books, 2007. ISBN 9781400096589.

- Monsaingeon, Bruno. Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations. Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 0571205534.

- Osborne, Richard. Herbert von Karajan. London: Chatto & Windus, 1998. ISBN 0701167149.

- —. Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000. ISBN 1555534252.

- Raymond, Holden. The Virtuoso Conductors. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300093268.

External links

All links retrieved December 20, 2017.

- Official Karajan website

- 1963 Stereo Review interview

- Tribute site to Herbert von Karajan

- Obituary by the New York Times

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.