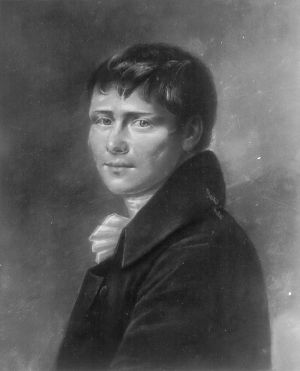

Heinrich von Kleist

Bernd Heinrich Wilhelm von Kleist (October 18, 1777 – November 21, 1811) was a German poet, dramatist, novelist, and short story writer. He was the first among the great German dramatists of the nineteenth century. The Kleist Prize, a prestigious prize for German literature, is named after him. A reading of Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, which systematized the epistemological doubt of Rene Descartes, throwing into doubt the certainty of human knowledge, caused Kleist to abandon the rationalism of the Enlightenment in favor of emotionalism. In this regard, Kleist was a precursor to Romanticism. He had the Romantics' predisposition toward extreme states of consciousness; his works were a precursor to those of Sigmund Freud and the unconscious.

Life

Kleist was born of aristocratic descent at Frankfurt an der Oder, on October 18, 1777. After a scanty education, he entered the Prussian army in 1792, serving in the Rhine campaign of 1796. Dissatisfied with military life, he resigned his commission, retiring from the service in 1799, with the rank of lieutenant, to study law and philosophy at Viadrina University, receiving a subordinate post in the ministry of finance at Berlin, in 1800.

In the following year, his roving, restless spirit got the better of him, and procuring a lengthened leave of absence, he visited Paris and then settled in Switzerland. Here he found congenial friends in Heinrich Zschokk and Ludwig Friedrich August Wieland (d. 1819), son of the poet Christoph Martin Wieland; and to them, he read his first drama, a gloomy tragedy, Die Familie Schroffenstein (1803), originally entitled Die Familie Ghonorez.

In the autumn of 1802, Kleist returned to Germany, visiting Goethe, Schiller and Wieland in Weimar, staying for a while in Leipzig and Dresden. He then went again to Paris, before returning in 1804, to his post in Berlin. He was transferred to the Domänenkammer (department for the administration of crown lands) at Königsberg. On a journey to Dresden in 1807, Kleist was arrested by the French as a spy, sent to France and kept for six months as a prisoner at Châlons-sur-Marne. On regaining his liberty, he proceeded to Dresden, where in conjunction with Adam Heinrich Müller (1779-1829), he published in 1808 the journal Phöbus.

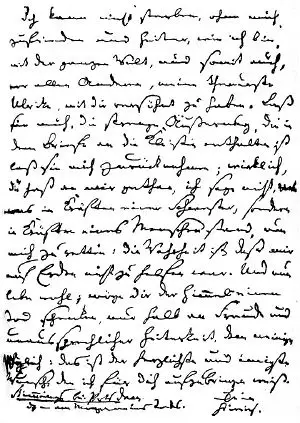

In 1809, he went to Prague, and ultimately settled in Berlin, where he edited (1810/1811) the Berliner Abendblätter. Captivated by the intellectual and musical accomplishments of a certain Frau Henriette Vogel, Kleist, who was himself more disheartened and embittered than ever, agreed to do her bidding and die with her, carrying out this resolution by first shooting Frau Vogel and then himself on the shore of the Kleiner Wannsee Lake in southwest Berlin, on November 21, 1811.

Kleist's whole life was filled by a restless striving after ideal and illusory happiness, and this is largely reflected in his work. He was by far the most important North German dramatist of the Romantic movement, and no other of the Romanticists approaches him in the energy with which he expresses patriotic indignation.

Literary works

His first tragedy, Die Familie Schroffenstein, was followed by Penthesilea (1808). The material for this second tragedy about the queen of the Amazons is taken from a Greek source and presents a picture of wild passion. While not particularly successful, it has been deemed by critics to contain some of Kleist's finest poetry. More successful than either of these was his romantic play, Das Käthchen von Heilbronn, oder Die Feuerprobe (1808), a poetic drama full of medieval bustle and mystery, which has retained its popularity.

In comedy, Kleist made a name with Der zerbrochne Krug (1811). Unsuccessfully produced by Goethe in Weimar, it is now considered among the finest German comedies for its skillful dialogue and subtle realism. Amphitryon (1808), an adaptation of Moliere's comedy written while in French prison, is of less importance. Of Kleist's other dramas, Die Hermannschlacht (1809) is a dramatic treatment of a historical subject and is full of references to the political conditions of his own times, namely the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte.

In it, he gives vent to his hatred of his country's oppressors. This, together with the drama, Prinz Friedrich von Homburg,—accounted as Kleist's best work—was first published by Ludwig Tieck in Kleist's Hinterlassene Schriften (1821). Robert Guiskard, a drama conceived on a grand plan, was left only as a fragment.

Kleist was also a master in the art of narrative, and of his Gesammelte Erzählungen (1810-1811), Michael Kohlhaas, in which the famous Brandenburg horse dealer in Martin Luther's day is immortalized, is one of the best German stories of its time. Das Erdbeben in Chili (in Eng. The Earthquake in Chile) and Die heilige Cäcilie oder die Gewalt der Musik are also fine examples of Kleist's story-telling, as is Die Marquise von O. His short narratives were a major influence for Franz Kafka's short stories. He also wrote patriotic lyrics in the context of the Napoleonic wars.

Apparently a Romantic by context, predilection, and temperament, Kleist subverts clichéd ideas of Romantic longing and themes of nature and innocence and irony, instead taking up subjective emotion and contextual paradox to show individuals in moments of crises and doubt, with both tragic and comic outcomes, but as often as not his dramatic and narrative situations end without resolution. Because Kleist’s works so often present an unresolved enigma and do so with careful attention to language, they transcend their period and have as much impact on readers and viewers today as they have had over the last two hundred years. He was a precursor of both modernism and postmodernism; his work receives as much attention from scholars today as it ever has.

Seen as a precursor to Henrik Ibsen and modern drama because of his attention to the real and detailed causes of characters’ emotional crises, Kleist was also understood as a nationalist poet in the German context of the early twentieth century, and was instrumentalized by Nazi scholars and critics as a kind of proto-Nazi author. To this day, many scholars see his play Die Hermannsschlacht (The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, 1808) as prefiguring the subordination of the individual to the service of the Volk (nation) that became a principle of fascist ideology in the twentieth century. Kleist reception of the last generation has repudiated nationalist criticism and concentrated instead mainly on psychological, structural and post-structural, philosophical, and narratological modes of reading.

Kleist wrote one of the lasting comedies and most staged plays of the German canon, Der zerbrochene Krug (The Broken Jug, 1803-05), in which a provincial judge gradually and inadvertently shows himself to have committed the crime under investigation. In the enigmatic drama, Prinz Friedrich von Homburg (1811), a young officer struggles with conflicting impulses of romantic self-actualization and obedience to military discipline. Prince Friedrich, who had expected to be executed for his successful but unauthorized initiative in battle, is surprised to receive a laurel wreath from Princess Natalie. To his question, whether this is a dream, the regimental commander Kottwitz replies, “A dream, what else?”

Kleist wrote his eight novellas later in his life and they show his radically original prose style, which is at the same time careful and detailed, almost bureaucratic, but also full of grotesque, ironic illusions and various sexual, political, and philosophical references. His prose often concentrates on minute details that then serve to subvert the narrative and the narrator, and throw the whole process of narration into question. In Die Verlobung in Santo Domingo (Betrothal in St. Domingo, 1811) Kleist examines the themes of ethics, loyalty, and love in the context of the colonial rebellion in Haiti of 1803, driving the story with the expected forbidden love affair between a young white man and a black rebel woman, though the reader's expectations are confounded in typically Kleistian fashion, since the man is not really French and the woman is not really black. Here, for the first time in German literature, Kleist addresses the politics of a race-based colonial order and shows, through a careful exploration of a kind of politics of color (black, white, and intermediate shades), the self-deception and ultimate impossibility of existence in a world of absolutes.

Philosophical essays

Kleist is also famous for his essays on subjects of aesthetics and psychology which, to the closer look, show an unfathomable insight into the metaphysical questions discussed by first-rate philosophers of his time, like Kant, Fichte, or Schelling.

In his first of his larger essays, Über die allmähliche Verfertigung der Gedanken beim Reden (On the Gradual Development of Thoughts in the Process of Speaking), Kleist shows the conflict of thought and feeling in the soul of humanity, leading to unforeseeable results through incidents that provoke the inner forces of the soul (which can be compared to Freud's notion of the "unconscious") to express themselves in a spontaneous flow of ideas and words, both stimulating one another to further development.

The metaphysical theory in and behind the text is that consciousness, humanity's ability to reflect, is the expression of a fall out of nature's harmony, which may lead to disfunction, when the flow of feelings is interrupted or blocked by thought or to the stimulation of ideas, when the flow of feelings is cooperating or struggling with thought, without being able to reach a state of total harmony, where thought and feeling, life and consciousness come to be identical through the total insight of the latter, an idea elaborated and analyzed in Kleist's second essay The Puppet Theatre (Das Marionettentheater).

The puppet seems to have just one center, and therefore, all its movements seem to be harmonious. Humans have two, his consciousness is sign of this rupture in his nature, hindering him to reach a harmonic state and destroying the mythical paradise of harmony with god, nature and himself. Only as a utopian ideal this state of perfection may lead our endless strife for improvement (one of Fichte's main ideas which seems to have crossed Kleist's thoughts).

And without saying this expressly, works of art, like Kleist's own, may offer an artificial image of this ideal, though this is in itself really wrenched out from the same sinful state of insufficiency and rupture that it wants to transcend.

Kleist's philosophy is the ironic rebuff of all theories of human perfection, whether this perfection is projected in a golden age at the beginning (Friedrich Schiller), in the present (Hegel), or in the future (as Marx would have seen it). It shows humanity, like the literary works, torn apart by conflicting forces and held together on the surface only by illusions of real love (if this was not the worst of all illusions). Josephe in Kleist's Earthquake in Chile is presented as emotionally and socially repressed and incapable of self-control, but still clinging to religious ideas and hopes. At the end of a process marked by chance, luck, and coincidence, and driven by greed, hatred, and the lust for power, embodied in a repressive social order, the human being that at the beginning had been standing between execution and suicide, is murdered by a mob of brutalized maniacs who mistake their hatred for religious feelings.

Major works

His Gesammelte Schriften were published by Ludwig Tieck (3 vols. 1826) and by Julian Schmidt (new ed. 1874); also by F. Muncker (4 vols. 1882); by T. Zolling (4 vols. 1885); by K. Siegen, (4 vols. 1895); and in a critical edition by E. Schmidt (5 vols. 1904-1905). His Ausgewählte Dramen were published by K. Siegen (Leipzig, 1877); and his letters were first published by E. von Bühlow, Heinrich von Kleists Leben und Briefe (1848).

- Plays

- Die Familie Schroffenstein, written 1802, published anonymously in 1803, premiered 9 January 1804 in Graz

- Robert Guiskard, Herzog der Normänner, written 1802–1803, published April/May 1808 in Phöbus, first performed on 6 April 1901 at the Berliner Theater in Berlin

- Der zerbrochne Krug (The Broken Jug), written 1803–1806, premiered 2 March 1808 at the Hoftheater in Weimar

- Amphitryon, written 1807, first performed on 8 April 1899 at the Neuen Theater in Berlin

- Penthesilea, completed 1807, published 1808, first performed in May 1876 at the Königlichen Schauspielhaus in Berlin

- Das Käthchen von Heilbronn oder Die Feuerprobe. Ein großes historisches Ritterschauspiel, written 1807–1808, partially published in Phöbus 1808, premiered 17 March 1810 at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna, revised and fully published in 1810

- Die Hermannsschlacht, written 1809, posthumously published 1821, first performed on 18 October 1860 in Breslau

- [Prinz Friedrich von Homburg (The Prince of Homburg), written 1809–1811, first performed on 3 October 1821 as Die Schlacht von Fehrbellin at the Burgtheater in Vienna

- Novellas and short stories

- Das Erdbeben in Chili (The Earthquake in Chile), published under the original title Jeronimo und Josephe 1807 in Cottas Morgenblatt für gebildete Stände; revised and included in 1810 in Erzählungen (Volume 1)

- Die Marquise von O...., published February 1808 in Phöbus; revised and included in 1810 in Erzählungen (Volume 1)

- Michael Kohlhaas. Aus einer alten Chronik, partially published June 1808 in Phöbus; included in 1810 in Erzählungen (Volume 1)

- Das Bettelweib von Locarno (The Beggarwoman of Locarno), published 11 October 1810 in the Berliner Abendblättern; included in 1811 in Erzählungen (Volume 2)

- Die heilige Cäcilie oder die Gewalt der Musik. Eine Legende (St. Cecilia or The Power of Music), published 15-17 November 1810 in the Berliner Abendblättern; expanded and included in 1811 in Erzählungen (Volume 2)

- Die Verlobung in St. Domingo (The Betrothal in Santo Domingo), published 25 March to 5 April 1811 in Der Freimüthige; revised and included in 1811 in Erzählungen (Volume 2)

- Der Findling (The Foundling), published in 1811 in Erzählungen (Volume 2)

- Der Zweikampf (The Duel), published 1811 in Erzählungen (Volume 2)

- Anekdoten, published 1810–1811 in the Berliner Abendblättern

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Jacobs, Carol. Uncontainable Romanticism: Shelley, Brontë, Kleist. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780801837869

- Maass, Joachim. Kleist: A Biography. Ralph Manheim, trans. Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1983. ISBN 9780374181628

- Meldrum Brown, Hilda. Heinrich Von Kleist The Ambiguity of Art and the Necessity of Form. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998. ISBN 9780198158950

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- Works by Heinrich von Kleist. Project Gutenberg (German)

- Heinrich von Kleist IMDb

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.