Haakon IV of Norway

| Håkon Håkonsson | ||

|---|---|---|

| King of Norway | ||

| Reign | 1217 – December 16 1263 | |

| Coronation | July 29 1247, old cathedral of Bergen | |

| Born | 1204 | |

| Varteig | ||

| Died | December 16 1263 | |

| Kirkwall, Orkney Islands | ||

| Buried | Old cathedral of Bergen | |

| Consort | Margrét Skúladóttir | |

| Issue | Olav (Óláfr) (1226-29) Håkon (Hákon) (Håkon the Young) (1232-1257) Christina (Kristín) (1234-62) Magnus (Magnús) (1238-1280)

| |

| Father | Håkon III Sverreson | |

| Mother | Inga of Varteig (died 1234) | |

Haakon Haakonsson (1204 – December 15, 1263) (Norwegian Håkon Håkonsson, Old Norse Hákon Hákonarson), also called Haakon the Old, was king of Norway from 1217 to 1263. Under his rule, medieval Norway reached its peak. A patron of the arts, he entered a trade treaty with Henry III of England and extended Norwegian rule over both Iceland and Greenland (61-62). He enjoyed cordial relations with the Church and Much of his reign was marked by internal peace and more prosperity than Norway had known for many years. This was the start of what has traditionally been known as the golden age of the Norwegian medieval kingdom.

Background and childhood

Håkon's mother was Inga of Varteig. She claimed he was the illegitimate son of Håkon III of Norway, the leader of the birkebeiner faction in the ongoing civil war against the bagler. Håkon III had visited Varteig, in what is now Østfold county, the previous year. He was dead by the time Håkon was born, but Inga's claim was supported by several of Håkon III's followers, and the birkebeiner recognized Håkon as a king's son.

The civil war era in Norwegian history lasted from 1130 to 1240. During this period there were several interlocked conflicts of varying scale and intensity. The background for these conflicts were the unclear Norwegian succession laws, social conditions and the struggle between different aristocratic parties and between Church and King. There were opposing factions, firstly known by varying names or no names at all, but finally condensed into the two parties birkebeiner and bagler. The rallying point regularly was a royal son, who was set up as the figurehead of the party in question, to oppose the rule of a king from the contesting party. Håkon's putative father Håkon III had already sought some reconciliation with the Bagler party and with exiled bishops. His death was early and poisoning was suspected. He was not married. After his death, the bagler started another rising leading to the de facto division of the country into a bagler kingdom in the south-east, and a birkebeiner kingdom in the west and north.

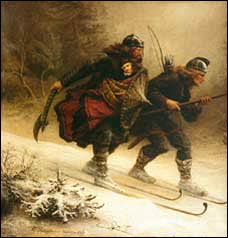

Håkon was born in territory controlled by the Bagler faction, and his mother's claim that he was a birkebeiner royal son placed them both in a very dangerous position. When in 1206 the Bagler tried to take advantage of the situation and started hunting Håkon, a group of Birkebeiner warriors fled with the child, heading for King Inge II of Norway, the birkebeiner king in Nidaros (now Trondheim). On their way they a blizzard developed, and only the two strongest warriors, Torstein Skevla and Skjervald Skrukka, continued on skis, carrying the child in their arms. They managed to bring the heir to safety. This event is still commemorated in Norway's most important annual skiing event, the Birkebeiner ski race.

Early reign

The rescued child was placed under the protection of King Inge Bårdsson. After King Inge's death in 1217, at the age of 13, he was chosen as king against the candidacy of Inge's half-brother, earl Skule Bårdsson. Skule, however, as earl, retained the real royal power. In connection with the dispute over the royal election, Håkon's mother Inga had to prove his parentage through a trial by ordeal in Bergen in 1218. The church at first refused to recognize him, partly on the ground of illegitimacy.

In 1223 a great meeting of all the bishops, earls, lendmenn and other prominent men was held in Bergen to finally decide on Håkon's right to the throne. The other candidates to the throne were Guttorm Ingesson, the 11-year-old illegitimate son of King Inge Bårdsson; Knut Haakonson, legitimate son of earl Haakon the Crazy, who resided in Västergötland, Sweden, with his mother Kristin; earl Skule, who based his claim on being the closest living relative - a legitimate brother - of king Inge; and Sigurd Ribbung, who was at the time a captive of earl Skule. Haakon was confirmed as king of Norway, as a direct heir of King Håkon Sverresson, king Inge's predecessor. A most important factor in his victory was the fact that the church now took Håkon's side, despite his illegitimate birth. However, the Pope's dispensation for his coronation was not gained until 1247.

In 1217, Philip Simonsson, the last Bagler king, died. Speedy political and military manoeuvering by Skule Bårdsson led to reconciliation between the birkebeiner and bagler, and the reunification of the kingdom. However, some discontented elements among the bagler found a new royal pretender, Sigurd Ribbung and launched a new rising in the eastern parts of the country. This was finally quashed in 1227, leaving Håkon more or less uncontested monarch.

In the earlier part of Håkon's reign much of the royal power was in the hands of Skule Bårdsson. From the start of his reign, it was decided that Skule should rule one third of the kingdom, as earl, and Skule helped put down the rising of Sigurd Ribbung. But the relationship between Skule and Håkon became more and more strained as Håkon came of age, and asserted his power. As an attempt to reconcile the two, in 1225 Håkon married Skule's daughter Margrét Skúladóttir. In 1239 the conflict between the two erupted into open warfare, when Skule had himself proclaimed king in Nidaros. The rebellion ended in 1240 when Skule was put to death. The rebellion also led to the death of Snorri Sturluson. Skule's other son-in-law, the one-time claimant Knut Håkonsson, did not join the revolt, but remained loyal to king Håkon. This rebellion is generally taken to mark the end of Norway's age of civil wars.

Later reign

From this time onward Håkon’s reign was marked by internal peace and more prosperity than Norway had known for many years. This was the start of what has traditionally been known as the golden age of the Norwegian medieval kingdom. In 1247 Håkon finally achieved recognition by the pope, who sent Cardinal William of Sabina to Bergen to crown him. Abroad, Håkon mounted a campaign against the Danish province of Halland in 1256. In 1261 the Norse community in Greenland agreed to submit to the Norwegian king, and in 1262, Håkon achieved one of his long-standing ambitions when Iceland, racked by internal conflict and prompted by Håkon's Icelandic clients, did the same. The kingdom of Norway was now the largest it has ever been. In 1263 a dispute with the Scottish king concerning the Hebrides, a Norwegian possession, induced Håkon to undertake an expedition to the west of Scotland. Alexander III of Scotland had conquered the Hebrides the previous year. Håkon retook the islands with his formidable leidang fleet, and launched some forays onto the Scottish mainland as well. A division of his army seems to have repulsed a large Scottish force at Largs (though the later Scottish accounts claim this battle as a victory). Negotiations between the Scots and the Norwegians took place, which were purposely prolonged by the Scots, as Håkon's position would grow more difficult the longer he had to keep his fleet together so far away from home. An Irish delegation approached Håkon with an offer to provide for his fleet through the winter, if Håkon would help them against the English. Håkon seems to have been favorable to this proposition, but his men refused. Eventually the fleet retreated to the Orkney Islands for the winter.

While Håkon was wintering in the Orkney Islands and staying in the Bishop's Palace, Kirkwall, he fell ill, and died on December 16 1263. A great part of his fleet had been scattered and destroyed by storms. Håkon was buried for the winter in St Magnus' Cathedral in Kirkwall. When spring came he was exhumed and his body taken back to Norway, where he was buried in the old cathedral in his capital, Bergen. This cathedral was demolished in 1531, the site is today marked by a memorial.

Dipomacy

In 1217 he entered a trade treaty with the English king. This is the earliest commercial treaty on record for both kingdoms. Håkon also entered negotiations with the Russians regarding border dispute and signed a treaty establishing their Northern boundary.

In 1250, he signed another commercial treaty with the German city of Lübeck. He passed laws outlawing blood feuds and a law confirming hereditary succession to the throne. From 800 until 1066 the Norwegians, with the Swedes and Danes were renowned as Viking raiders although they also engaged in trade. Now, Norway was becoming more interested in commerce than in surviving by striking terror into the hearts of people across the seas so skillfully sailed by her long-boats.

Culture

Håkon wanted to transform his court into one that compared favorable with "those in European" where culture and learning flourished. He commissioned translations of Latin texts into the vernacular.<ref>Pulsiano and Wolf, page 258.<.ref>

Succession

On his deathbed Håkon declared that he only knew of one son who was still alive, Magnus, who subsequently succeeded him as king. Magnus' succession was confirmed by the bishops. The bishops role in the confirmation process "validated the principles concerning ecclesiastical influence the succession." Hereditary succession to the throne of the eldest legitimate son was thus established in "collaboration with the Church" since an "older, illegitimate half-brother" was bypassed. Pulsiano and Wolf comment that "practical cooperation" with the Church characterized Håkon's reign.<ref>Pulsiano and Wolf, page 258.<.ref>

In 1240, a group of Bjarmians told Håkon that they were refugees from the Mongols. He gave them land in Malangen.

Legacy

Norwegian historians have held strongly differing views on Håkon Håkonsson's reign. In the 19th century, the dominant view was of Håkon as the mighty king, who ended the civil wars and ruled over the largest Norwegian empire ever. The historian P. A. Munch represents this view. In the 1920s came a reaction. Håkon was now seen by many as an insignificant and average man, who happened to be king at a time of greatness for the Norwegian kingdom. This has often been stated by Marxist historians. The historian Halvdan Koht is typical of this view. Håkon has often been compared with Skule Bårdsson, his last rival, with modern historians taking sides in this 700-year-old conflict. He is also inevitably compared with his grandfather, King Sverre, and most historians tend to conclude that he wasn't quite the dynamic and charismatic leader that Sverre was. Recently, the historian Sverre Bagge and others have emphasized the fact that much of what we know about both Håkon and Sverre comes from their respective official biographies. Therefore what we might know about their individual character and personality is only what the authors of these have chosen to reveal to us, and therefore depends heavily on these authors' motivation in writing a biography. A comparison between Håkon and Sverre on these grounds seems arbitrary and unfair.

What remains clear is that Håkon was born in a war-torn society plagued by armed gangs and warlords, and died the undisputed ruler of a large and internationally respected kingdom. Håkon received embassies and exchanged gifts with rulers as far afield as Tunis, Novgorod and Castile. At his court, chivalric romances and Biblical stories were translated into the old Norse language, notably the translations linked to the cleric Brother Robert, and Håkon presided over several large-scale construction projects in stone, a novelty in Norway at that time. The great hall which he had built at his palace in Bergen (Håkonshallen) can still be seen today.

Our main source of information concerning Håkon is Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar (Håkon Håkonsson's saga) which was written in the 1260s, only a few years after his death. It was commissioned by his son Magnus, and written by the Icelandic writer and politician Sturla Þórðarson, nephew of the famous historian Snorri Sturluson.

A literary treatment of Håkon's struggle with Skule can be found in Henrik Ibsen's play The Pretenders (1863).

Descendants

By his mistress, Kanga the Young:

- Sigurd (Sigurðr) (<1225-1254)

- Cecilia (<1225-1248). She married Gregorius Andresson, a nephew of the last bagler king Filippus Simonsson. Widowed, she later married king Harald (Haraldr) of the Hebrides, a vassal of King Håkon, in Bergen. They both drowned on the return voyage to the British Isles.

By his wife Margrét Skúladóttir:

- Olav (Óláfr) (1226-29). Died in infancy.

- Håkon (Hákon) (Håkon the Young) (1232-1257). Married Rikitsa Birgersdóttir, daughter of the Swedish earl Birger. Was appointed king and co-ruler by his father in 1239, he died before his father.

- Christina (Kristín) (1234-62). Married the Spanish prince, Felipe, brother of King Alfonso X of Castile in 1258. She died childless.

- Magnus (Magnús) (1238-1280). Was appointed king and co-ruler following the death of Håkon the Young. Crowned as king in 1261 on the occasion of his wedding to the Danish princess Ingibjörg.

The appointment of co-rulers was meant to ensure the peaceful succession in case the king should die - as long as Håkon was still alive he was still the undisputed ruler of the kingdom.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bagge, Sverre. 1996. From gang leader to the Lord's anointed: kingship in Sverris saga and Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar. Odense, Denmark: Odense University Press. ISBN 9788778381088.

- Dasent, George Webbe, Sturla Þorðarson, and Sturla Þorðarson. 1894. Icelandic sagas and other historical documents relating to the settlements and descents of the Northmen on the British Isles. Vol.4, The saga of Hakon and a fragment of the saga of Magnus, with appendices. Chronicles and memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages. London: Printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office by Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- Derry, T. K. 1979. A history of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816608355

- Ibsen, Henrik, 2007. The Pretenders. Eastbourne: Gardners Books. ISBN 9780548341520.

- Koht, Halfdan. 1929. "The Scandinavian Kingdoms until the end of the thirteenth century". 362-92.Cambridge Mediaeval History. VI, Ch. XI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pulsiano, Phillip, and Kirsten Wolf. 1993. Medieval Scandinavia: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland. ISBN 9780824047870

- Snorri Sturluson, and Lee Milton Hollander. 1964. Heimskringla: history of the kings of Norway. Austin: Published for the American-Scandinavian Foundation by the University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292730618.

External links

| House of Sverre Cadet Branch of the Fairhair dynasty Born: 1204; Died: December 15 1263 | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Preceded by: Inge Bårdsson |

King of Norway 1217-1263 |

Succeeded by: Magnus the Law-mender |

Template:Monarchs of Norway

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.