Great Pyramid of Giza

| Great Pyramid of Giza | |

Great Pyramid of Giza was the world's tallest building from c. 2570 B.C.E. to c. 1300 C.E.*

| |

| Preceded by | Red Pyramid of Sneferu, Egypt |

| Surpassed by | Lincoln Cathedral |

| Information | |

|---|---|

| Location | Giza, Egypt |

| Status | Complete |

| Constructed | c. 2570 B.C.E. |

| Height | |

| Roof | 138.8 m, 455.2 ft (Originally: 146.6 m, 480.9 ft) |

|

*Fully habitable, self-supported, from main entrance to highest structural or architectural top. | |

The Great Pyramid is the oldest and the largest of the three pyramids in the Giza Necropolis bordering what is now Cairo, Egypt in Africa. The oldest and only remaining member of the Seven Wonders of the World, it is believed to have been constructed over a 20 year period concluding around 2560 B.C.E.[1] The Great Pyramid was built as a tomb for Fourth dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu (hellenized as Χεωψ, Cheops), and is sometimes called Khufu's Pyramid or the Pyramid of Khufu.[2]

Historical context

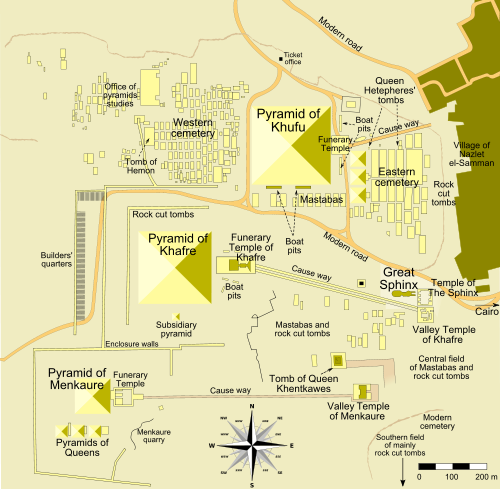

The Great Pyramid is the main part of a complex setting of buildings that included two mortuary temples in honour of Khufu (one close to the pyramid and one near the Nile), three smaller pyramids for Khufu's wives, an even smaller "satellite" pyramid, a raised causeway connecting the two temples, and small mastaba tombs surrounding the pyramid for nobles. One of the small pyramids contains the tomb of queen Hetepheres (discovered in 1925), sister and wife of Sneferu and the mother of Khufu. There was a town for the workers of Giza, including a cemetery, bakeries, a beer factory and a copper smelting complex. More buildings and complexes are being discovered by The Giza Mapping Project.

A few hundred metres south-west of the Great Pyramid lies the slightly smaller Pyramid of Khafre, one of Khufu's successors who is also commonly considered the builder of the Great Sphinx, and a few hundred metres further south-west is the Pyramid of Menkaure, Khafre's successor, which is about half as tall.

The generally accepted estimated date of its completion is c. 2500 B.C.E.[1] Although this date contradicts radiocarbon dating evidence[3] it is loosely supported by a lack of archaeological findings for the existence prior to the fourth dynasty of a civilization with sufficient population or technical ability in the area.

Khufu's vizier, Hemon, is credited as the architect of the Great Pyramid.[3]

Construction theories

Materials and workforce

Many varied estimates have been made regarding the workforce needed to construct the Great Pyramid. Herodotus, the Greek historian in the 5th century B.C.E., estimated that construction may have required 100,000 workers for 20 years. Recent evidence has been found that suggests the workforce was in fact paid [citation needed], which would require accounting and bureaucratic skills of a high order. Polish architect Wieslaw Kozinski believed that it took as many as 20 men to transport a 1.5-ton stone block. Based on this, he estimated the workforce to be 300,000 men on the construction site, with an additional 60,000 off-site. 19th century Egyptologist William Flinders Petrie proposed that the workforce was largely composed not of slaves but of the rural Egyptian population, working during periods when the Nile river was flooded and agricultural activity suspended.[4] Egyptologist Miroslav Verner posited that the labor was organized into a hierarchy, consisting of two gangs of 100,000 men, divided into five zaa or phyle of 200 men each, which may have been further divided according to the skills of the workers.[5] Some research suggests alternate estimates to the accepted workforce size. For instance, mathematician Kurt Mendelssohn calculated that the workforce may have been 50,000 men at most, while Ludwig Borchardt and Louis Croon placed the number at 36,000. According to Verner, a workforce of no more than 30,000 was needed in the Great Pyramid's construction.[4]

A construction management study (testing) carried out by the firm Daniel, Mann, Johnson, & Mendenhall in association with Mark Lehner and other Egyptologists, estimates that the total project required an average workforce of 14,567 people and a peak workforce of 40,000. Without the use of pulleys, wheels, or iron tools, they surmise the Great Pyramid was completed from start to finish in approximately 10 years.[6] Their critical path analysis study reveals estimates that the number of blocks used in construction was between 2-2.8 million (an average of 2.4 million), but settles on a reduced finished total of 2 million after subtracting the estimated area of the hollow spaces of the chambers and galleries.[6] Most sources agree on this number of blocks somewhere above 2.3 million.[7] The Egyptologists' calculations suggest the workforce could have sustained a rate of 180 blocks per hour (3 stones/minute) with ten hour work days for putting each individual block in place. They derived these estimates from construction projects that did not use modern machinery.[6] This study fails to take into account however, especially when compared to modern third world construction projects, the logistics and craftsmanship time inherent in constructing a building of nearly unparalleled magnitude with such precision, or among other things, the use of up to 60-80 ton stones being quarried and transported a distance of over 500 miles.

In contrast, a Great Pyramid feasibility study relating to the quarrying of the stone was performed in 1978 by Technical Director Merle Booker of the Indiana Limestone Institute of America. Consisting of 33 quarries, the Institute is considered by many architects to be one of the world’s leading authorities on limestone. Using modern equipment, the study concludes:

- “Utilizing the entire Indiana Limestone industry’s facilities as they now stand [for 33 quarries], and figuring on tripling present average production, it would take approximately 27 years to quarry, fabricate and ship the total requirements.”

Booker points out the time study assumes sufficient quantities of railroad cars would be available without delay or downtime during this 27 year period and does not factor in the increasing costs of completing the work.[8]

The entire Giza Plateau is believed to have been constructed over the reign of five pharaohs in less than a hundred years. In the hundred years prior to Giza, beginning with Djoser who ruled from 2687-2667 B.C.E., three other massive pyramids were built - the Step pyramid of Saqqara (believed to be the first Egyptian pyramid), the Bent Pyramid, and the Red Pyramid. Also during this period (between 2686 and 2498 B.C.E.) the Wadi Al-Garawi dam which used an estimated 100,000 cubic meters of rock and rubble was built.[9]

The accepted values by Egyptologists bear out the following result: 2,400,000 stones used ÷ 20 years ÷ 365 days per year ÷ 10 work hours per day ÷ 60 minutes per hour = 0.55 stones laid per minute.

Thus no matter how many workers were used or in what configuration, 1.1 blocks on average would have to be put in place every 2 minutes, ten hours a day, 365 days a year for twenty years to complete the Great Pyramid within this time frame. This equation, however, does not take into account among other things the designing, planning, surveying, and leveling the 13 acre site the Great Pyramid sits on.

Layout

Papyrus documents [citation needed] and existing cubit measuring rods give us the units of measure used to specify the plan of the pyramid and so it is thought that, at construction, the Great Pyramid was 280 Egyptian royal cubits tall (146.6 meters or 480.9 feet), but with erosion and the theft of its topmost stone (the pyramidion) its current height is 455.2 feet approximately 138.8 m. Each base side was 440 royal cubits, with each royal cubit measuring 0.523/4m (20.63 inches).[10] Thus, the base was originally almost 231 m on a side and covered approximately 53,000 square metres with a slope angle of 51.50.40 degrees (seked = 5½)—.

Today each side of the pyramid has an approximate length of about 230.4 meters(755.8 feet). The reduction in size and area of the structure into its current rough-hewn appearance is due to the absence of its original polished casing stones, some of which measured up to two and a half metres thick and weighed more than 15 tonnes.

In the 14th century (1301 C.E.), a massive earthquake loosened many of the outer casing stones, which were then carted away by Bahri Sultan An-Nasir Nasir-ad-Din al-Hasan in 1356 in order to build mosques and fortresses in nearby Cairo; the stones can still be seen as parts of these structures to this day. Later explorers reported massive piles of rubble at the base of the pyramids left over from the continuing collapse of the casing stones which were subsequently cleared away during continuing excavations of the site. Nevertheless, many of the casing stones around the base of the Great Pyramid can be seen to this day in situ displaying the same workmanship and precision as has been reported for centuries.

The first precision measurements of the pyramid were done by Sir Flinders Petrie in 1880–82 and published as "The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh".[11] Almost all reports are based on his measurements. Petrie found the pyramid is oriented 4' West of North and the second pyramid is similarly oriented. Petrie also found a different orientation in the core and in the casing ( – 5 ft 16 in ± 10"). Petrie suggested a redetermination of north was made after the construction of the core, but a mistake was made, and the casing was built with a different orientation. This deviation from the north in the core, corresponding to the position of the stars b-Ursae Minoris and z-Ursae Majoris about 3,000 years ago, takes into account the precession of the axis of the Earth. A study by egyptologist Kate Spence, shows how the changes in orientation of 8 pyramids corresponds with changes of position of those stars through time. This would date the start of the construction of the pyramid at 2467 B.C.E.[12]

For four millennia it was the world's tallest building, unsurpassed until the 160 metre tall spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed c. 1300. The accuracy of the pyramid's workmanship is such that the four sides of the base have a mean error of only 58 mm in length, and 1 minute in angle from a perfect square. The base is horizontal and flat to within 15 mm. The sides of the square are closely aligned to the four cardinal compass points to within 3 minutes of arc and is based not on magnetic north, but true north. The design dimensions, as confirmed by Petrie's survey and all those following this, are assumed to have been 280 cubits in height by 4x440 cubits around originally, and as these proportions equate to 2xpi to an accuracy of better than 0.05%, this was and is considered to have been the deliberate design proportion, by Professors Flinders Petrie, I.E.S Edwards and Verner [13] amongst many other Egyptologists. Other proportions of the King's Chamber supported this conclusion, and discussion continues as to the possible methods of implementation, in light of information regarding 'seked' slope angle techniques and geometrical problems concerning pyramids from the Rhind Papyrus.

The pyramid was constructed of cut and dressed blocks of limestone, basalt or granite. The core was made mainly of rough blocks of low quality limestone taken from a quarry at the south of Khufu’s Great Pyramid. These blocks weighed from two to four tonnes on average, with the heaviest used at the base of the pyramid. An estimated 2.4 million blocks were used in the construction. High quality limestone was used for the outer casing, with some of the blocks weighing up to 15 tonnes. This limestone came from Tura, about 8 miles away on the other side of the Nile. Granite quarried nearly 500 miles away in Aswan with blocks weighing as much as 60-80 tonnes, was used for the King's Chamber and relieving chambers.

The total mass of the pyramid is estimated at 5.9 million tonnes with a volume (including an internal hillock) believed to be 2,600,000 cubic metres. The pyramid is the largest in Egypt and the tallest in the world. It is surpassed only by the Great Pyramid of Cholula in Puebla, Mexico, which, although much lower in height, occupies a greater volume.

At completion, the Great Pyramid was surfaced by white 'casing stones' – slant-faced, but flat-topped, blocks of highly polished white limestone. These caused the monument to shine brightly in the sun, making it visible from a considerable distance. Visibly all that remains is the underlying step-pyramid core structure seen today, but several of the casing stones can still be found around the base. The casing stones of the Great Pyramid and Khafre's Pyramid (constructed directly beside it) were cut to such optical precision as to be off true plane over their entire surface area by only 1/50th of an inch. They were fitted together so perfectly that the tip of a knife cannot be inserted between the joints even to this day.

The passages inside the pyramid are all extremely straight and precise, such that the longest of them, referred to as the descending passage, which is 350' 0.25" long deviates from being truly straight by less than 0.25 inches, while one of the shorter passages with a length of just over 150 feet deviates from being truly straight by a mere 0.020 inches.

The Great Pyramid differs in its internal arrangement from the other pyramids in the area. The greater number of passages and chambers, the high finish of parts of the work, and the accuracy of construction all distinguish it. The walls throughout the pyramid are totally bare and uninscribed, but there are inscriptions — or to be more precise, graffiti — believed to have been made by the workers on the stones before they were assembled. All the five relieving chambers are inscribed. The most famous inscription is one of the few that mentions the name of Khufu; it says "year 17 of Khufu's reign". Although alternative theorists have suggested otherwise, given its precarious location it is hard to believe it could have been inscribed after construction; even Graham Hancock[14] accepted this, after Dr Hawass let him examine the inscription. Another inscription refers to "the friends of Khufu", and probably was the name of one of the gangs of workers[15]. Though this doesn't offer indisputable proof Khufu originated the construction of the Great Pyramid or when building began, it does appear however to clear any doubt he at least took part in some phase of its construction (or later repairs to an existing building) during his reign.

There are three known chambers inside the Great Pyramid. These are arranged centrally, on the vertical axis of the pyramid. The lowest chamber (the "unfinished chamber") is cut into the bedrock upon which the pyramid was built. This chamber is the largest of the three, but totally unfinished, only rough-cut into the rock.

The middle chamber, or Queen's Chamber, is the smallest, measuring approximately 5.74 by 5.23 metres, and 4.57 metres in height. Its eastern wall has a large angular doorway or niche, and two narrow shafts, about 20 centimeters wide, extending from the chamber towards the outer surface of the pyramid. These shafts were explored using a robot, Upuaut 2, created by Rudolf Gantenbrink. Upuat 2 discovered that these shafts were blocked by limestone "doors" with eroded copper "handles". During Pyramids Live: Secret Chambers Revealed, National Geographic filmed the drilling of a small hole in the southern door only to find another larger door behind it. The northern passage (which was harder to navigate due to twists and turns) was also found to have a door. Egyptologist Mark Lehner believes that the Queen's chamber was intended as a serdab—a structure found in several other Egyptian pyramids—and that the niche would have contained a statue of the interred. The Ancient Egyptians believed that the statue would serve as a "back up" vessel for the Ka of the Pharaoh, should the original mummified body be destroyed. The true purpose of the chamber, however, remains a mystery.[16]

At the end of the lengthy series of entrance ways leading into the pyramid interior is the structure's main chamber, the King's Chamber. This chamber was originally 10 x 20 x 11.2 cubits, or about 17 x 34 x 19 ft, comprising a double 10x10 cubit square, and a height equal to half the double square's diagonal. This is consistent with then-available geometric methods for determining the Golden Ratio phi, which can be derived from other dimensions of the pyramid, such that if phi had been the design objective, then pi automatically follows to 'square the circle'. [4] Given that pre-hellenistic Egyptians did not have a similar geometric way to determine pi as accurately, it is unlikely that it was preferred over phi as a design objective, especially as phi has been found in other pre-hellenistic Egyptian monuments. (Alexander Badawi. Ancient Egyptian Architectural Design. Berkeley: 1965)

The other main features of the Great Pyramid consist of the Grand Gallery, the sarcophagus found in the King's Chamber, both ascending and descending passages, and the lowest part of the structure mentioned above, what is dubbed the "unfinished chamber".

The Grand Gallery (49 x 3 x 11 m) features an ingenious corbel halloed design and several cut "sockets" spaced at regular intervals along the length of each side of its raised base with a "trench" running along its center length at floor level. What purpose these sockets served is unknown. The Red Pyramid of Dashur also exhibits grand galleries of similar design.

The sarcophagus of the King's chamber was hollowed out of a single piece of Red Aswan granite and has been found to be too large to fit through the passageway leading to the King's chamber. Whether the sarcophagus was ever intended to house a body is unknown, but it is too short to accommodate a medium height individual without the bending of the knees (a technique not practised in Egyptian burial) and no lid was ever found.

The "unfinished chamber" lies 90 ft below ground level and is rough-hewn, lacking the precision of the other chambers. This chamber is dismissed by Egyptologists as being nothing more than a simple change in plans in that it was intended to be the original burial chamber but later King Khufu changed his mind wanting it to be higher up in the pyramid.[17] Considering the extreme precision and planning given to every other phase of the Great Pyramid's construction, this conclusion seems surprising.

Two French amateur Egyptologists, Gilles Dormion and Jean-Yves Verd'hurt, claimed in August 2004 that they had discovered a previously unknown chamber inside the pyramid underneath the Queen's Chamber using ground-penetrating radar and architectural analysis. They believe the chamber to be unviolated and could contain the king's remains. They believe the King's Chamber, the chamber generally assumed to be Khufu's original resting place, was not constructed to be a burial chamber.[18]

Dating evidence

Traditionally, the evidence for dating the Great Pyramid by Egyptologists has been based primarily on fragmented summaries of early Christian writings gleaned from the work of the Hellinistic Period Egyptian priest Manethô who compiled the now lost revisionist Egyptian history Aegyptika. These works, and to a lesser degree earlier Egyptian sources, mainly the "Turin Canon" and "Table of Abydos" among others, combine to form the main body of historical reference for Egyptologists giving a timeline by popular consensus of rulers known as the "King's List", found in the reference archive; the Cambridge Ancient History [19][20]. As a result, being Egyptologists have ascribed the pyramid to Khufu, establishing the time he reigned by default subsequently dates the monument as well as the confines for its completion of construction.

The Edgar Cayce Foundation, researching claims that the pyramids were at least 10,000 years old, funded the "David H. Koch Pyramids Radiocarbon Project" in 1984. The project took samples of organic material (such as ash and charcoal deposits) from several locations within the Great Pyramid, and other pyramids and monuments from the Old Kingdom period (ca. 3rd millennium B.C.E.). These samples were subjected to radiocarbon dating to produce calibrated date-equivalent estimates of their age. This yielded results averaging 374 years earlier than the estimated historical date accepted by Egyptologists (2589 – 2504 B.C.E.) but still more recent than 10,000 years ago.[21] An astronomical study by Kate Spence suggests the pyramid dates to 2467 B.C.E.[12]

A second dating in 1995 with new but similar material obtained dates ranging between 100-400 years earlier than those indicated by the historic record. This raised questions concerning the origin and date of the wood. Massive quantities of wood were used and burned, so to reconcile the earlier dates the authors of the study theorized that possibly "old wood" was used, assuming that wood was harvested from any source available, including old construction material from all over Egypt. It is also known, given the poor quality and relative scarcity of native Egyptian woods, that King Sneferu (and later Egyptian pharohs) imported fine woods from Lebanon and other countries such as Nubia for the creation of decorative furniture, royal boats (as found buried around the Giza Plateau), or other luxuries generally reserved for royalty[22]. But as Mark Lehner points out such efforts were not without "great cost"[23]. It is unknown, given the expense, effort, and value of such woods, if they were ever imported as an expendable source of industrial fuel, especially on such a large scale.

Project scientists based their conclusions on the evidence that some of the material in the 3rd Dynasty pyramid of Pharaoh Djoser and other monuments had been recycled, concluding that the construction of the pyramids marked a major depletion of Egypt's exploitable wood. Dating of more short-lived material around the pyramid (cloth, small fires, etc) yielded dates nearer to those indicated by historical records. As of yet the full data of the study has yet to be released[24] in which the authors insist more evidence is needed to settle this issue. In the absence of the "old wood" theory, the study admits "The 1984 results left us with too little data to conclude that the historical chronology of the Old Kingdom was in error by nearly 400 years, but we considered this at least a possibility." [21]

In his book Voyages of the Pyramid Builders [24], Boston University geology professor Robert Schoch details key anomalies in both radiocarbon studies; most notably that samples taken in 1984 from the upper courses of the Great Pyramid gave upper dates of 3809 B.C.E. (± 160yrs), nearly 1400yrs before the time of Khufu, while the lower courses provided dates ranging from 3090-2723 B.C.E. (± 100-400yrs) which correspond much more closely to the time Khufu is believed to have reigned. Given that the data imply the pyramid was built (impossibly) from the top down, Dr. Schoch argues that if the information provided by the study is correct, it makes sense if it is assumed the pyramid was built and rebuilt in several stages suggesting later Pharaohs such as Khufu were only inheritors of an existing monument, not the original builders, and merely rebuilt or repaired previously constructed sections.

Alternative theories

In common with many other monumental structures from antiquity, the Great Pyramid has over time been the subject of a great number of speculative or alternative theories, which put forward a variety of explanations about its origins, dating, construction and purpose. In support of these claims such accounts either rely upon novel reinterpretations of the available data from fields such as archaeology, history and astronomy, or appeal to biblical, mythological, mystical, numerological, astrological and other esoteric sources of knowledge, or some combination of these.

Such ideas have been part of popular culture since at least the turn of the 20th century and can be traced back among others to such figures as the early-twentieth century American psychic Edgar Cayce, whose "psychic channeling" of "Ra Ta" purports to have conveyed that the pyramids were built by refugees from Atlantis, and even to his predecessor Ignatius L. Donnelly. In recent years, some of the more widely-publicized writers of alternative theories include Graham Hancock, Robert Bauval, John Anthony West, and Boston University geology professor Robert M. Schoch. These have written extensive alternative theories about the age and origin of the Giza pyramids and the Sphinx. While many Egyptologists and field scientists tend to dismiss such accounts out of hand as being a form of pseudoarchaeology, other specialists such as astronomy professor Ed Krupp who have been involved in the debate have put forward astronomical refutations based on the presented evidence for several of their claims.[25] The proponents have in their turn presented their counter-rebuttals.[26][27][28]

A theme found in some of the alternative theories put forward concerning the Giza pyramids and many other megalithic sites around the world, is the suggestion that these are not the products of the civilizations and cultures known to conventional history, but are instead the much older remnants of some hitherto unknown advanced ancient culture. This progenitor civilization is supposed to have been destroyed in antiquity by some devastating catastrophe brought about by the end of the last ice age, according to most of these accounts sometime around 10,000 B.C.E. For the Great Pyramid of Giza in particular, it is maintained (depending on the theorist) that either it was ordained and built by this now-vanished civilization, or else that its construction was somehow influenced by knowledge (now lost) acquired from this civilization. The latter point of view is more common among recent theorists such as Hancock and Bauval, who believe that the Great Pyramid incorporates star shafts 'locked in' to Orion's Belt and Sirius at around 2450 B.C.E., though they argue the Giza ground-plan was laid out in 10,450 B.C.E.[29]

The a priori existence of such a civilization is postulated by such theorists who believe this is the only reasonable explanation for how the most advanced of ancient cultures, such as Egypt and Sumer, were able to reach such high levels of unequaled technological advancement with what they claim is little or no precedent. This precedent they argue exists in the form of megalithic ruins found all over the globe discovered at the beginnings of history but too complex, they argue, to have been constructed by the cultures they are ascribed to by the mainstream. As another of these theorists John Anthony West writes in reference to Egypt in particular: "How does a complex civilization spring full blown into being? Look at a 1905 automobile and compare it to a modern one. There is no mistaking the process of 'development'. But in Egypt there are no parallels. Everything is right there from the start."[30]

Another alternative theory, put forward by a group who often refer to themselves as "pyramidologists", is that the Pyramid is a divine revelation, planned by prophets who influenced pharaoh Khufu. The founder of this group, Adam Rutherford, author of the four-volume set Pyramidology, drew from two primal texts bringing attention to the Great Pyramid in the West, Oxford astronomy professor John Greaves 1646 book Pyramidography, and John Taylor's The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built and Who Built It? (1859). Rutherford, Dr. Gene Scott[5], Larry Pahl[6], and others in this group claim that the Pyramid passage systems, when measured with the "Pyramid inch", contain a prophetic timeline which reveals the date of creation, the building of the Pyramid, the exodus from Egypt, and the birth and crucifixion of Christ.

It should be noted that all of these theories are disregarded by mainstream Egyptologists and archaeologists.

See also

- List of Egypt-related topics

- Archaeology

- Measures and Mathematics

- Pyramid inch

- World's tallest free standing structure on land

- The Upuaut Project

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (January 21, 2004) (2006) The Seven Wonders. The Great Pyramid of Giza.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, New York, 2001. Edited by Dana M Collins. Volume 2, Page 234.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael, "Egyptian Art: The Mysterious Lure of an Old Friend", The New York Times, 1999-09-17. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 (2006) Tour Egypt.Pyramid Workforce

- ↑ The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments, Oxbow Books: October 2001, 432 pages (ISBN 0-8021-1703-1)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Civil Engineering magazine, June 1999

- ↑ Khufu's Inside Story

- ↑ pgs. 104-105, 5/5/2000, Richard Noone, 1982 Three rivers Press, New York ISBN 0-609-80067-1

- ↑ (September 16-22, 2004)(2006) Al Ahram. The World's Oldest Dam

- ↑ O.A.W. Dilke, Mathematics and Measurement, University of California Press/British Museum, 1987, 9&23

- ↑ Birdsall, Ronald. The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 (November 15, 2000) (2006) New Scientist. Pyramid precision

- ↑ Verner, M. The Pyramids, their archaeology and history 1997 pp70

- ↑ [1] Graham Hancock

- ↑ Miroslav Werner, The Pyramids – Their Archaeology and History p.455, "From a paleographic, grammatical and historical point of view, there is not the slightest doubt as their authenticity"]

- ↑ Winston, Alan. The Pyramid of Khufu at Giza in Egypt. InterCity Oz, Inc.

- ↑ Unfinished Chamber. PBS

- ↑ (2003)(2006) Tour Egypt. Secret Chambers of the Great Pyramid of Khufu by Jimmy Dunn.

- ↑ "http://www.phouka.com/pharaoh/egypt/history/00kinglists.html"

- ↑ "http://www.friesian.com/notes/oldking.htm"

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 (September/October 1999) (2006) Archeology Dating the Pyramids Volume 52 Number 5 by members of the David H. Koch Pyramids Radiocarbon Project

- ↑ http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/furniture.htm

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/1915mpyramid.html

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Schoch, Robert M. (2003). Voyages of the Pyramid Builders. Penguin Books, 14-18. ISBN 1585422037. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Schoch2003" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Krupp, Ed (March 2001). The Sphinx Blinks. Sky & Telescope 101 (3): pp.86–88.

- ↑ Correspondence between Hancock, Bauval and Krupp concerning Giza-Orion Correlation and Kate Spence's Nature article

- ↑ The Orion Correlation Theory and Ed Krupp

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ (2006) Graham Hancock. Like a Thief in the Night

- ↑ (1979)(2006). Serpent in the Sky.

External links

Archaeology

Exploration

- Travelers in Egypt

- 3d walkthru model of the Great Pyramid inside

- The Upuaut Project Homepage; information about robotic expeditions and CAD drawings of airshafts

- Real-Time 3D tour around Giza

Other theories

- Ron Wyatt [7]

- Vincent Brown's Pyramid of Man

- Pyramids in relation with the Noble Quraan (Quran)

- Wall, John, "The Wrong Question (or: The Myth of the Mystery of the Missing Messages)". In the Hall of Maat.

- World-Mysteries.com - Mystic Places : The Great Pyramid

- Composition of Giza Plateau

- Ottar Vendel's Age of the Pyramids

- Pyramid construction theory

- Joseph Davidovits' "Ari-Kat Technology" - Geopolymer theory of pyramid construction

- Maureen Clemmons' "How Many Caltechers Does It Take to Raise An Egyptian Obelisk?" - Wind power construction theory

- W.T. Wallington's "[8] - Moving and hoisting of heavy weights without wheels, rollers and ropes

- Chris Dunn "[9]" - The Theory that the Giza Pyramid was a giant Maser

- Ralph Ellis The Great Pyramid as a map.

- The Speed of Light in Stone at The Giza Plateau "[10]"

News

- Guardian's Pyramids of Egypt

- Secret chamber may hold key to mystery of the Great Pyramid (The Guardian, August 30 2004.)

- Amateur archaeologists track lost tomb of Cheops (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, August 30 2004.)

- Pyramid Construction: Ancient ramp leading to the Great Pyramid discovered, but only of maximal height approximately 100 feet (30 m). Pyramid's original height was 481 feet. Also, the heaviest stone blocks were discovered to have holes bored on opposite sides, indicating the use of cranes (or other mechanical means) to raise and precisely position them.

Images

- Satellite image of Khufu's Pyramid (29°58'51"N 31°09'00"E) - at WikiMapia = Google maps + wiki

- A Picture Tour of The Great Pyramid at the Great Pyramid of Giza Research Association.

- Fullscreen Quicktime VR Panorama' Pyramids of Giza

- Pyramid of Giza Images

- Pyramidcam!

- digital.egypt - QTVR fullscreen panoramas on Giza Plateau

- Egypt Pyramids Pictures of Pyramids in Giza published under Creative Commons License

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.