Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert, stretching into modern day China and Mongolia, expands its harsh rocky terrain over 500,000 square miles. Unlike the romanticized image of deserts with sweeping sand dunes, most of the landscape of the Gobi consists of rocky, hard packed terrain. While the solid land under foot made it easier to transverse the desert, catipulting the Gobi onto the scene of history as a viable trade route, there was very little settled human occupation in the area until modern times. A clue to the historical perception of the Gobi as an unhospitable region is found in its name, whoch derives from the Mongolian word for "very large and dry." The Gobi Desert is Asia's largest desert[1].

The modern Gobi Desert is roughly cresent-shaped, lying between the Altai and Hangayn mountain ranges in the north and the Pei Mountains in the south. The eastern side of the desert is fringed by the Sinkiang region, a large basin that extends towards the Plateau of Tibet. Towards the west of the Gobi lies the Greater Khingan Range. The large area of the Gobi Desert is often broken into smaller sections, or ecoregions, in order to aid study of the region.

Geography

Ecoregions of the Gobi

The Gobi, is catagorized by teh World Wildlife Federation as consisting of two broadly defined ecoregions: The Gobi Steppe Desert and the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe region.

The Eastern Gobu Desert Steppe lies in the eastern portion of the Gobi Desert, reaching from the Inner Mongolia Palteau(found in China) into Mongolia. Overall, this region covers an area of approximately 108,800 square miles before its borders fade into the lush grasslands of MOngolia and Manchuria. Salt marshes and small ponds are commonly found in the lower elevations in this area, but disapear when the elevation rises to form the Yin Shan Mountain Range. The Eastern Gobi Desert Steppe is caratorized by drought adapted plantlife and occasional thin wild grass patches.The Gobi Desert also harbors a few plant species that have been useful for both animals and humans alike , including: wormwood, wild garlic, saltwort, and wild onion.

While the harsh environment and lack of visisble vegetation may make the Gobi Desert appear inhospitable and unoccupied, the reverse appears to be true upon closer examinantion. The desert teems with life, boasting particularly large populations of Asian wild ass , Saiga antelope , black-tailed gazelle , and marbled polecat. Smaller animals and insects also contribute to the desert ecosystem, along with sizable bird populations.

The other ecosystem recognized by the World Wildlife Federation in the Gobi Desert is the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe, situated between the Khangai range and the Gobi-Altai and Mongol-Altai ranges in southwestern MOngolia. The Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe is actually quite small for a complete ecosystem, measuring only 500 km long and 150 km wide. Despite its size, however, the region offers a broad range of lanscape diversity, ranging from sand dunes to salt marshes. The most distinct feature of the area, however, and the one that earned the region its name, is the large number of lakes that dot the landscape. These lakes, mainly the Orog, Boontsagaan, Taatsyn tsagaan, and the Ulaan nuur provide an unusual geographic feature for an area techically classified as a desert.

Like the East Gobi Desert Steppe, all the plant life found in the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Stepp region has adapted to the harsh conditions of life in the desert. In addition to the plants found in the East Gobi, the lakes of this region support a thriving aquatic community complete with marine animals and water dwelling plant forms. Lakes and marshes also provide a valuable habitat for bird communities.

In regards to the mammalian occupants of the Gobi Lakes Valley, most of the species are able to survive in the difficult terrain by using the terrain to their best advantage. Common species found in the Gobi include: Midday gerbil, dwarf hamster, long-eared hedgehog, and the Tibetan hare. Smaller animals like these are able to hide in the shade during the heat of the day and avoid direct exposure to the glaring midday sun. Some larger animals, however, also choose to make the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe their home, including :black-tailed Gazelle, Mongolian gazelle, and wild mountain sheep in the more montainous regions.

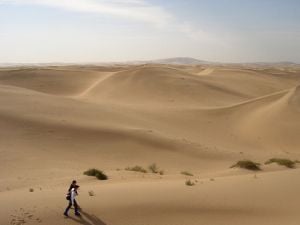

Sands of the Gobi Deserts

Depsite the fact that much of the Gobi desert consists of gravel or rocky terrain, the few sand dunes that due exist continue to draw scientific inquiry and toursts alike. There are two major theories about the origins of the sand dunes in Mongolia. One theory, which is the more popular theory among scientists, states that the sands where flown into the desert on wind currents, much the way that water can carry sand. This theory has gained popularity as science as been able to track wind currents in the region, and the sand dunes have been proven to have developed along traditional wind paths. While this is the more predominant theory, an alternative idea exists that claims the sand dunes were originally a product of water erosion.

Climate

The Gobi Desert is noted for its extreme tempature variation, with days commonly dipping from sweltering midday heat to freezing temaptures at night. During the winter, the Gobi Desert experiences extremely low temaptures that are not found in other surrounding areas of China and MOngolia. The reason for the the cooler temaptures, like the formation of the sand dunes, is the strong winds that sweep across the plains of the Gobi Desert. Unstopped by any significant mountain formations, the winds add a chill to the tempature that makes life in the winter Gobi Desert particularly difficult.

The summer season, while marked by temaptures rising towards 100°, is the rainy season for the Gobi Desert. The high tempatures bring with them the promise of rain, which is much needed for the inhabitants of the desert. While a welcome respite from the heat, the rains never seem to last long enough, annually only dropping about 100 to 150 mm on the plains.

Conservation Efforts

The grasslands of the Gobi Desert are under extreme threat and may one day completely disappear if current practices in the region continue. The main culprit for the degregation of the grasslands is overgrazing by goats in the region, whose sheerings fetch a high price in the form of cashmere. The problem of overgrazing has become compounded in recent years, as more and more people return to a agricultural lifestyle after the destruction of much of the urban economy of Mongolia.

The increase of agriculturalists in the area also threatens to detach much of the sand and topsoil in the desert. UNder this threat, the loose sand or topsoil potentially could be swept away by the winds. This process is known as desertification, and is common situation faced by deserts around the world.

On a scientific level, the Gobi Desert has also proven to be a valuable resource that needs to be conserved for future generations. The Gobi Desert harbors rich fossil remains, including dinosaur eggs and bones. Particularly the Gobi Desert has been used to study the phenomenon commonly refered to as a "sand slides", where particle matter shifted on to living animals. This process, which resulted in death and physical preservation of the body, provides an important component for analysing the extinction of dinosaurs.

History

This great desert country of Gobi is crossed by several trade routes, some of which have been in use for thousands of years. Among the most important are those from Kalgan on the frontier of China to Ulaanbaatar (960 km), from Suzhou (in Gansu) to Hami (670 km) from Hami to Beijing (2000 km), from Kwei-hwa-cheng (or Kuku-khoto) to Hami and Barkul, and from Lanzhou (in Gansu) to Hami.

European exploration up to 1911

The Gobi had a long history of human habitation, mostly by nomadic peoples. By the early 20th century the region was under the nominal control of China, and inhabited mostly by Mongols, Uyghurs, and Kazakhs. The Gobi desert as a whole was only very imperfectly known to outsiders, information being confined to the observations which individual travellers had made from their respective itineraries across the desert. Amongst the European explorers who contributed to early 20th century understanding of the Gobi, the most important were:

- Marco Polo (1273-1275)

- Jean-François Gerbillon (1688-1698)

- Eberhard Isbrand Ides (1692-1694)

- Lorenz Lange (1727-1728 and 1736)

- Fuss and Alexander G. von Bunge (1830-1831)

- Hermann Fritsche (1868-1873)

- Pavlinov and Z.L. Matusovski (1870)

- Ney Elias (1872-1873)

- N.M. Przhevalsky (1870-1872 and 1876-1877)

- Zosnovsky (1875)

- Mikhail V. Pevtsov (1878)

- Grigory N. Potanin (1877 and 1884-1886)

- Count Béla Széchenyi and Lajos Lóczy (1879-1880)

- The brothers Grum-Grzhimailo (1889-1890)

- Pyotr Kuzmich Kozlov (1893-1894 and 1899-1900)

- Vsevolod I. Roborovsky (1894)

- Vladimir A. Obruchev (1894- 1896)

- Karl Josef Futterer and Dr. Holderer (1896)

- Charles-Etienne Bonin (1896 and 1899)

- Sven Hedin (1897 and 1900-1901)

- K. Bogdanovich (1898)

- Ladyghin (1899-1900) and Katsnakov (1899-1900)

See also

- Geography of China

- Geography of Mongolia

- Battle of Ikh Bayan

- List of deserts by area

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- ↑ Wright, John W. (ed.) and Editors and reporters of The New York Times (2006). The New York Times Almanac, 2007, New York, New York: Penguin Books, 456. ISBN 0-14-303820-6.

Further reading

- Cable, Mildred and French, Francesca. 1943. The Gobi Desert. London. Landsborough Publications.

- Man, John. 1997. Gobi : Tracking the Desert. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Paperback by Phoenix, Orion Books. London. 1998.

- Stewart, Stanley. 2001. In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey among Nomads. HarperCollinsPublishers, London. ISBN 0-00-653027-3.

External links

- Map, from "China the Beautiful"

- Flickr: Photos tagged with gobi

- Gobi Desert in Google Earth Requires Google Earth

| Deserts |

|---|

| Ad-Dahna | Alvord | Arabian | Aral Karakum | Atacama | Baja California | Barsuki | Betpak-Dala | Chalbi | Chihuahuan | Dasht-e Kavir | Dasht-e Lut | Dasht-e Margoh | Dasht-e Naomid | Gibson | Gobi | Great Basin | Great Sandy Desert | Great Victoria Desert | Kalahari | Karakum | Kyzylkum | Little Sandy Desert | Mojave | Namib | Nefud | Negev | Nubian | Ordos | Owyhee | Qaidam | Registan | Rub' al Khali | Ryn-Peski | Sahara | Saryesik-Atyrau | Sechura | Simpson | Sonoran | Strzelecki | Syrian | Taklamakan | Tanami | Thar | Tihamah | Ustyurt |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.