Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert, stretching into modern day China and Mongolia, expands its harsh rocky terrain over 500,000 square miles. Unlike the romanticized image of deserts with sweeping sand dunes, most of the landscape of the Gobi consists of rocky, hard packed terrain. While the solid land under foot made it easier to transverse the desert, catipulting the Gobi onto the scene of history as a viable trade route, there was very little settled human occupation in the area until modern times. A clue to the historical perception of the Gobi as an unhospitable region is found in its name, whoch derives from the Mongolian word for "very large and dry." The Gobi Desert is Asia's largest desert[1].

The modern Gobi Desert is roughly cresent-shaped, lying between the Altai and Hangayn mountain ranges in the north and the Pei Mountains in the south. The eastern side of the desert is fringed by the Sinkiang region, a large basin that extends towards the Plateau of Tibet. Towards the west of the Gobi lies the Greater Khingan Range. The large area of the Gobi Desert is often broken into smaller sections, or ecoregions, in order to aid study of the region.

Geography

Ecoregions of the Gobi

The Gobi, is catagorized by teh World Wildlife Federation as consisting of two broadly defined ecoregions: The Gobi Steppe Desert and the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe region.

The Eastern Gobu Desert Steppe lies in the eastern portion of the Gobi Desert, reaching from the Inner Mongolia Palteau(found in China) into Mongolia. Overall, this region covers an area of approximately 108,800 square miles before its borders fade into the lush grasslands of MOngolia and Manchuria. Salt marshes and small ponds are commonly found in the lower elevations in this area, but disapear when the elevation rises to form the Yin Shan Mountain Range. The Eastern Gobi Desert Steppe is caratorized by drought adapted plantlife and occasional thin wild grass patches.The Gobi Desert also harbors a few plant species that have been useful for both animals and humans alike , including: wormwood, wild garlic, saltwort, and wild onion.

While the harsh environment and lack of visisble vegetation may make the Gobi Desert appear inhospitable and unoccupied, the reverse appears to be true upon closer examinantion. The desert teems with life, boasting particularly large populations of Asian wild ass , Saiga antelope , black-tailed gazelle , and marbled polecat. Smaller animals and insects also contribute to the desert ecosystem, along with sizable bird populations.

The other ecosystem recognized by the World Wildlife Federation in the Gobi Desert is the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe, situated between the Khangai range and the Gobi-Altai and Mongol-Altai ranges in southwestern MOngolia. The Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe is actually quite small for a complete ecosystem, measuring only 500 km long and 150 km wide. Despite its size, however, the region offers a broad range of lanscape diversity, ranging from sand dunes to salt marshes. The most distinct feature of the area, however, and the one that earned the region its name, is the large number of lakes that dot the landscape. These lakes, mainly the Orog, Boontsagaan, Taatsyn tsagaan, and the Ulaan nuur provide an unusual geographic feature for an area techically classified as a desert.

Like the East Gobi Desert Steppe, all the plant life found in the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Stepp region has adapted to the harsh conditions of life in the desert. In addition to the plants found in the East Gobi, the lakes of this region support a thriving aquatic community complete with marine animals and water dwelling plant forms. Lakes and marshes also provide a valuable habitat for bird communities.

In regards to the mammalian occupants of the Gobi Lakes Valley, most of the species are able to survive in the difficult terrain by using the terrain to their best advantage. Common species found in the Gobi include: Midday gerbil, dwarf hamster, long-eared hedgehog, and the Tibetan hare. Smaller animals like these are able to hide in the shade during the heat of the day and avoid direct exposure to the glaring midday sun. Some larger animals, however, also choose to make the Gobi Lakes Valley Desert Steppe their home, including :black-tailed Gazelle, Mongolian gazelle, and wild mountain sheep in the more montainous regions.

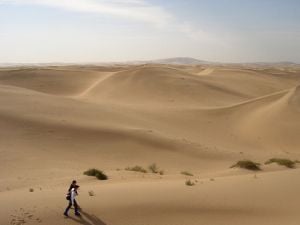

Sands of the Gobi Deserts

The origins of the of sand that make up the dunes (or barchans) in the Gobi are a source of debate. Some explorers consider them a product of marine or lacustrine denudation (ie. erosion). Most likely, however, the sands are the result of aerial denudation of the bordering mountain ranges and the remains of mountain ranges and hills within the Gobi itself. In this latter view, the winds would have a similar effect and obey similar laws as rivers and streams carrying sediment do in moister parts of the world.

Potanin points out that there is a certain amount of regularity observable in the distribution of the sandy deserts over the vast uplands of central Asia. Two agencies are represented in the distribution of the sands, though what they really are is not quite clear; and of these two agencies one prevails in the north-west, the other in the south-east, so that the whole of Central Asia may be divided into two regions, the dividing line between them being drawn from north-east to south-west, from Ulaanbaatar via the eastern end of the Tian Shan to the city of Kashgar. North-west of this line the sandy masses are broken up into detached and disconnected areas, and are almost without exception heaped up around the lakes, and consequently in the lowest parts of the several districts in which they exist. Moreover, we find also that these sandy tracts always occur on the western or south-western shores of the lakes; this is the case with the lakes of Balkash, Ala-kul, Ebi-nor, Ayar-nor (or Telli-nor), Orku-nor, Zaisan-nor, Ulungur-nor, Ubsa-nor, Durga-nor and Kara-nor lying east of Kirghiz-nor. South-east of the line the arrangement of the sand is quite different. In that part of Asia we have three gigantic but disconnected basins. The first, lying farthest east, is embraced on the one side by the ramifications of the Kentei and Khangai Mountains and on the other by the In-shan Mountains. The second or middle division is contained between the Altay of the Gobi and the Ala-shan. The third basin, in the west, lies between the Tian Shan and the border ranges of western Tibet. The deepest parts of each of these three depressions occur near their northern borders; towards their southern boundaries they are all alike very much higher. However, the sandy deserts are not found in the low-lying tracts but occur on the higher uplands which foot the southern mountain ranges, the In-shan and the Nan-shan. Our maps show an immense expanse of sand south of the Tarim in the western basin; beginning in the neighbourhood of the city of Yarkent (Yarkand),it extends eastwards past the towns of Khotan, Kenya and Cherchen to Sa-chow. Along this stretch there is only one locality which forms an exception to the rule we have indicated, namely, the region round the lake of Lop-nor. In the middle basin the widest expanse of sand occurs between the Edzin-gol and the range of Ala-shan. On the south it extends nearly as far as a line drawn through the towns of Lian-chow, Kan-chow and Kao-tai at the foot of the Nan-shan; but on the south it does not approach anything like so far as the latitude (42° north) of the lake of Ghashiun-nor. Still farther east come the sandy deserts of Ordos, extending southeastward as far as the mountain range which separates Ordos from the (Chinese) provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi. In the eastern basin drift-sand is encountered between the district of Ude in the north (44° 30'north) and the foot of the In-shan in the south. In two regions, if not in three, the sands have overwhelmed large tracts of once cultivated country, and even buried the cities in which men formerly dwelt. These regions are the southern parts of the desert of Takla Makan (where Sven Hedin and A. Stein have discovered the ruins under the desert sands), along the north foot of the Nan-shan, and probably in part (other agencies having helped) in the north of the desert of Lop, where Sven Hedin discovered the ruins of Lou-lan and of other towns or villages. For these vast accumulations of sand are constantly in movement; though the movement is slow, it has nevertheless been calculated that in the south of the Takla Makan the sand dunes travel bodily at the rate of roughly 50 m in a year. The shape and arrangement of the individual sand dunes, and of the barkhans, generally indicate from which direction the predominant winds blow. On the windward side of the dune the slope is long and gentle, while the leeward side is steep and in outline concave like a horse shoe. The dunes vary in height from 10-100 m, and in some places mount as it were upon one another's shoulders, and in some localities it is even said that a third tier is sometimes superimposed.

Climate

The climate of the Gobi is one of great extremes, combined with rapid changes of temperature, not only through the year but even within 24 hours (by as much as 32 °C or 58 °F).

| Ulaanbaatar (1150 m) | Sivantse (1190 m) | |

|---|---|---|

| Annual mean | -2.5 °C (27 °F) | +2.8 °C (37 °F) |

| January mean | -26.5 °C (-15.7 °F) | -16.5 °C (2 °F) |

| July mean | 17.5 °C (63.5 °F) | 19.0 °C (66 °F) |

| Extremes | 38.0 °C and -43 °C (100 °F and -45 °F) | 33.9 °C and -47 °C (93 °F and -52 °F) |

Even in southern Mongolia the thermometer goes down as low as -32.8 °C (-27 °F), and in Ala-shan it rises as high as 37 °C (98.6 °F) in July.

Average winter minimals are a frigid -40 °C (-40 °F) while summertime temperatures are warm to hot, highs range up to 45 °C (113 °F). Most of the precipitation falls during the summer.

Although the southeast monsoons reach the southeast parts of the Gobi, the area throughout this region is generally characterized by extreme dryness, especially during the winter. Hence, the icy sandstorms and snowstorms of spring and early summer.

Conservation Efforts

The Gobi Desert is the source of many important fossil finds, including the first dinosaur eggs.

These deserts and the surrounding regions sustain many animals, including black-tailed gazelles, marbled polecats, and sandplovers, and are occasionally visited by snow leopards, brown bears, and wolves. The desert features a number of drought-adapted shrubs such as gray sparrow's saltwort, gray sagebrush, and low grasses such as needle grass and bridlegrass.

The area is vulnerable to trampling by livestock and off-road vehicles (human impacts are greater in the eastern Gobi Desert, where rainfall is heavier and may sustain livestock). In Mongolia, grasslands have been degraded by goats, raised by nomadic herders as source of cashmere wool. Economic trends of livestock privatization and the collapse of the urban economy have caused people to return to rural lifestyles, a movement contrary to urbanization. This movement has resulted in a great increase of nomadic herder population and livestock raising.

Large copper and gold deposits are located at Oyu Tolgoi, about 80 kilometers from the Chinese border into Mongolia and the feasibility of setting up a mining operation is being investigated.[1]

History

This great desert country of Gobi is crossed by several trade routes, some of which have been in use for thousands of years. Among the most important are those from Kalgan on the frontier of China to Ulaanbaatar (960 km), from Suzhou (in Gansu) to Hami (670 km) from Hami to Beijing (2000 km), from Kwei-hwa-cheng (or Kuku-khoto) to Hami and Barkul, and from Lanzhou (in Gansu) to Hami.

European exploration up to 1911

The Gobi had a long history of human habitation, mostly by nomadic peoples. By the early 20th century the region was under the nominal control of China, and inhabited mostly by Mongols, Uyghurs, and Kazakhs. The Gobi desert as a whole was only very imperfectly known to outsiders, information being confined to the observations which individual travellers had made from their respective itineraries across the desert. Amongst the European explorers who contributed to early 20th century understanding of the Gobi, the most important were:

- Marco Polo (1273-1275)

- Jean-François Gerbillon (1688-1698)

- Eberhard Isbrand Ides (1692-1694)

- Lorenz Lange (1727-1728 and 1736)

- Fuss and Alexander G. von Bunge (1830-1831)

- Hermann Fritsche (1868-1873)

- Pavlinov and Z.L. Matusovski (1870)

- Ney Elias (1872-1873)

- N.M. Przhevalsky (1870-1872 and 1876-1877)

- Zosnovsky (1875)

- Mikhail V. Pevtsov (1878)

- Grigory N. Potanin (1877 and 1884-1886)

- Count Béla Széchenyi and Lajos Lóczy (1879-1880)

- The brothers Grum-Grzhimailo (1889-1890)

- Pyotr Kuzmich Kozlov (1893-1894 and 1899-1900)

- Vsevolod I. Roborovsky (1894)

- Vladimir A. Obruchev (1894- 1896)

- Karl Josef Futterer and Dr. Holderer (1896)

- Charles-Etienne Bonin (1896 and 1899)

- Sven Hedin (1897 and 1900-1901)

- K. Bogdanovich (1898)

- Ladyghin (1899-1900) and Katsnakov (1899-1900)

See also

- Geography of China

- Geography of Mongolia

- Battle of Ikh Bayan

- List of deserts by area

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- ↑ Wright, John W. (ed.) and Editors and reporters of The New York Times (2006). The New York Times Almanac, 2007, New York, New York: Penguin Books, 456. ISBN 0-14-303820-6.

Further reading

- Cable, Mildred and French, Francesca. 1943. The Gobi Desert. London. Landsborough Publications.

- Man, John. 1997. Gobi : Tracking the Desert. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Paperback by Phoenix, Orion Books. London. 1998.

- Stewart, Stanley. 2001. In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey among Nomads. HarperCollinsPublishers, London. ISBN 0-00-653027-3.

External links

- Map, from "China the Beautiful"

- Flickr: Photos tagged with gobi

- Gobi Desert in Google Earth Requires Google Earth

| Deserts |

|---|

| Ad-Dahna | Alvord | Arabian | Aral Karakum | Atacama | Baja California | Barsuki | Betpak-Dala | Chalbi | Chihuahuan | Dasht-e Kavir | Dasht-e Lut | Dasht-e Margoh | Dasht-e Naomid | Gibson | Gobi | Great Basin | Great Sandy Desert | Great Victoria Desert | Kalahari | Karakum | Kyzylkum | Little Sandy Desert | Mojave | Namib | Nefud | Negev | Nubian | Ordos | Owyhee | Qaidam | Registan | Rub' al Khali | Ryn-Peski | Sahara | Saryesik-Atyrau | Sechura | Simpson | Sonoran | Strzelecki | Syrian | Taklamakan | Tanami | Thar | Tihamah | Ustyurt |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.