Difference between revisions of "Gnosticism" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Gnostic sects) |

m (→Creation) |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

===Manicheism=== | ===Manicheism=== | ||

Manichaeism, a gnostic religion that originated in third century Babylon (a province of Persia at the time), reached, over the span of the next ten centuries, from North Africa to China. Named after its prophet, Mani, its teachings moved west into Syria, Northern Arabia, Egypt and North Africa, where the future Saint Augustine was a member of its school from 373-382. From Syria it progressed into Palestine, Asia Minor, and Armenia. There is evidence for Manicheans in Rome and Dalmatia in the foruth century, and also in Gaul and Spain. Many of the members of earlier Christian gnostic sects may have been dawn into its orbit. | Manichaeism, a gnostic religion that originated in third century Babylon (a province of Persia at the time), reached, over the span of the next ten centuries, from North Africa to China. Named after its prophet, Mani, its teachings moved west into Syria, Northern Arabia, Egypt and North Africa, where the future Saint Augustine was a member of its school from 373-382. From Syria it progressed into Palestine, Asia Minor, and Armenia. There is evidence for Manicheans in Rome and Dalmatia in the foruth century, and also in Gaul and Spain. Many of the members of earlier Christian gnostic sects may have been dawn into its orbit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Cathars-Expelled.jpg|thumb|250px|Cathars expelled from France.]] | ||

Manicheanism was attacked by imperial edicts and polemical writings, but the religion remained strong in the western Roman Empire until the sixth century. In the east, Manicheanism was able to bloom. In the early years of the Arab conquest, Manicheanism again found followers in Persia and flourished especially in Central Asia, where it had spread through Iran. Here, in 762, Manicheanism became the state religion of the Uigar Empire. | Manicheanism was attacked by imperial edicts and polemical writings, but the religion remained strong in the western Roman Empire until the sixth century. In the east, Manicheanism was able to bloom. In the early years of the Arab conquest, Manicheanism again found followers in Persia and flourished especially in Central Asia, where it had spread through Iran. Here, in 762, Manicheanism became the state religion of the Uigar Empire. | ||

| Line 93: | Line 95: | ||

===Creation=== | ===Creation=== | ||

| − | The "classical" gnostic mythology posits a sort of prologue to the Judeo-Christian version of creation as described in the Book of Genesis. It speaks of an unknown God, defined as immovable, invisible, intangible, and ineffable. God is seen as being androgynous, both male and female, and "all-containing" or sometimes "the uncontained." God may also be referred to as the ''[[Monad]]'', or the first [[Aeon]]. In gnosticism, God cannot be accurately described in any positive sense through words; it is more possible to say what God isn't. It is only in experiencing God through ''gnosis'' that the Deity can be truly understood — but this, too, defies verbal description. | + | The "classical" gnostic mythology posits a sort of prologue to the Judeo-Christian version of creation as described in the Book of Genesis. It speaks of an unknown God, defined as immovable, invisible, intangible, and ineffable. God is seen as being androgynous, both male and female, and "all-containing" or sometimes "the uncontained." God may also be referred to as the ''[[Monad]]'', or the first [[Aeon]]. In gnosticism, God cannot be accurately described in any positive sense through words; it is more possible to say what God isn't. It is only in experiencing God through ''gnosis'' that the Deity can be truly understood — but this, too, defies verbal description. |

| + | |||

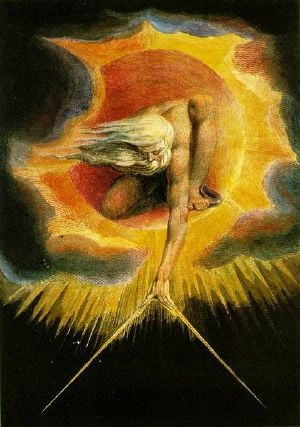

| + | [[Image:Ancient-of-Days.jpg|thumb|Blake's "Ancient of Days"]] | ||

:He did not lack anything, that he might be completed by it; rather he is always completely perfect in light. He is illimitable, since there is no one prior to him to set limits to him. He is unsearchable, since there exists no one prior to him to examine him. He is immeasurable, since there was no one prior to him to measure him. He is invisible, since no one saw him. He is eternal, since he exists eternally. He is ineffable, since no one was able to comprehend him to speak about him. He is unnameable, since there is no one prior to him to give him a name. He is immeasurable light, which is pure, holy, immaculate. He is ineffable, being perfect in incorruptibility. (He is) not in perfection, nor in blessedness, nor in divinity, but he is far superior. He is not corporeal nor is he incorporeal. He is neither large nor is he small. There is no way to say, 'What is his quantity?' or, 'What is his quality?', for no one can know him. | :He did not lack anything, that he might be completed by it; rather he is always completely perfect in light. He is illimitable, since there is no one prior to him to set limits to him. He is unsearchable, since there exists no one prior to him to examine him. He is immeasurable, since there was no one prior to him to measure him. He is invisible, since no one saw him. He is eternal, since he exists eternally. He is ineffable, since no one was able to comprehend him to speak about him. He is unnameable, since there is no one prior to him to give him a name. He is immeasurable light, which is pure, holy, immaculate. He is ineffable, being perfect in incorruptibility. (He is) not in perfection, nor in blessedness, nor in divinity, but he is far superior. He is not corporeal nor is he incorporeal. He is neither large nor is he small. There is no way to say, 'What is his quantity?' or, 'What is his quality?', for no one can know him. | ||

| Line 103: | Line 107: | ||

In some versions of the myth, one of the first aeons was Christos, or Christ, who was later sent to earth as the savior. In others, Christ appears to embody several of the characteristics of the first aeons. One Valentinian list (the genealogies vary quite significantly) list identifies the following generations of aeons: | In some versions of the myth, one of the first aeons was Christos, or Christ, who was later sent to earth as the savior. In others, Christ appears to embody several of the characteristics of the first aeons. One Valentinian list (the genealogies vary quite significantly) list identifies the following generations of aeons: | ||

| − | ''First generation'' | + | ''First generation'': Bythos or the Monad (the One) |

| − | :Bythos or the Monad (the One) | + | |

| − | ''Second generation'' | + | ''Second generation'': Caen (Power) and Akhana (Love) |

| − | :Caen (Power) and Akhana (Love) | + | |

| − | ''Third generation, emanated from Caen and Akhana'' | + | ''Third generation, emanated from Caen and Akhana'': Nous (Nus, Mind) and Aletheia (Veritas, Truth) |

| − | :Nous (Nus, Mind) and Aletheia (Veritas, Truth) | + | |

| − | ''Fourth generation, emanated from Nous and Aletheia'' | + | ''Fourth generation, emanated from Nous and Aletheia'': Sermo (the Word) and Vita (the Life) |

| − | :Sermo (the Word) and Vita (the Life) | + | |

| − | ''Fifth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita'' | + | ''Fifth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita'': Anthropos (Humanity) and Ecclesia (Church) |

| − | :Anthropos ( | + | |

| − | ''Sixth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita'' | + | ''Sixth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita'': Bythios (Profound) and Mixis (Mixture), Ageratos (Never old) and Henosis (Union), Autophyes (Essential nature) and Hedone (Pleasure), Acinetos (Immovable) and Syncrasis (Commixture), Monogenes (Only-begotten) and Macaria (Happiness); ''emanated from Anthropos and Ecclesia'': Paracletus (Comforter) and Pistis (Faith), Patricas (Paternal) and Elpis (Hope), Metricos (Maternal) and Agape (Love), Ainos (Praise) and Synesis (Intelligence), Ecclesiasticus (Son of Ecclesia) and Macariotes (Blessedness), Theletus (Perfect) and Sophia (Wisdom). |

| − | :Bythios (Profound) and Mixis (Mixture), Ageratos (Never old) and Henosis (Union), Autophyes (Essential nature) and Hedone (Pleasure), Acinetos (Immovable) and Syncrasis (Commixture), Monogenes (Only-begotten) and Macaria (Happiness) | ||

| − | '' | ||

| − | :Paracletus (Comforter) and Pistis (Faith), Patricas (Paternal) and Elpis (Hope), Metricos (Maternal) and Agape (Love), Ainos (Praise) and Synesis (Intelligence), Ecclesiasticus (Son of Ecclesia) and Macariotes (Blessedness), Theletus (Perfect) and Sophia (Wisdom). | ||

At this point in the gnostic cosmology, the universe was still entirely non-material. However, the emanations of God into increasing numbers of aeons led, eventually, to potential instability within the primordial universe. This reached a critical point with the appearance of the aeon most distant from the origin, [[Sophia]] (Greek for "wisdom"). | At this point in the gnostic cosmology, the universe was still entirely non-material. However, the emanations of God into increasing numbers of aeons led, eventually, to potential instability within the primordial universe. This reached a critical point with the appearance of the aeon most distant from the origin, [[Sophia]] (Greek for "wisdom"). | ||

Revision as of 02:57, 7 August 2006

Gnosticism is a general term describing various mystically oriented groups and their teachings, which were most prominent in the first few centuries C.E.. It is also applied to later and modern revivals of these teachings. The term gnosticism comes from the Greek word for knowledge, gnosis (γνώσις), referring esoteric consciousness, a key to transcendent understanding, self-realization, and/or unity with God.

The origins of gnosticism are controversial. Some scholars believe it to be of Eastern origin because of its similarities to Buddhist ideas of englightenment, while others believe it have Mesopotamian, Hellenistic, or even Jewish roots. Gnostic groups became popular around the same time and often in the same places that Christianity did. Indeed, gnosticism was widespread within the early Christian church until the gnostics were expelled in the second and third centuries. The response of othodoxy to gnosticism singificantly defined the evolution of Christian doctrine and church order. Gnostic Christianity continued as a separate movement from orthodoxy in some areas for centuries.

Christian gnostic groups portrayed Jesus as the greatest of gnostic teachers, and number of gnostic ideas seem to have been adopted into orthodox Christianity, while other gnostic doctrines were specifically rejected. Gnosticism was one of the first ideas to be specifically declared a heresy, and Gnostic movements both within and outside of the Christian chruch have often been persecuted as a result. Gnosticism has reappeared in various forms throughout history and into the contemporary era.

Sources

There are two main historical sources for information on gnosticism: critiques by ancient orthodox Chruch Fathers and the original gnostic works.

Gnostics were prolific producers of sacred literature, and there were considerably more gnostic scriptures written than orthodox ones. However, until the late 19th and the 20th centuries, no early gnostic literature was available except in isolated quotations in the writings of their opponents. Scholars in the 19th century devoted considerable effort to collecting the scattered references in the works of opponents and reassembling the gnostic materials.

Several important finds of gnostic manuscripts have been made since, most importantly the so-called Nag Hammadi library. But though we now possess a large collection of gnostic texts, they are still often difficult to interpret, due to the esoteric nature of gnostic teaching and difficulties in identifying which teachers or sects were associated with particular texts.

Gnosticism and Christianty

Many gnostic sects were made up of Christians who embraced mystical theories of the nature of Jesus. The Gospel of Thomas, an early semi-gnostic collection of Jesus' sayings, represents this tendency. In this account, Jesus institutes no sacraments, and his death and resurrection are never mentioned. His role is not to die for mankind's sins, but to impart knowledge to those of his disciples who are able to receive it. "Whoever discovers the interpretation of these sayings," the gospel begins, "will not taste death." Thus it is not by faith in Jesus, but by knowing the true meaning of his teachings, that the believer will enter into eternal life.

While gnosticism was a highly diverse and flexible phenomenon, certain elements can be identified as typifying the movement in its Christian manifestation.

- Gnostics tended toward a dualistic view in which matter was seen as essentially illusory.

- Christian gnostics emphasized spiritual knowledge and experience, rather than faith and the sacraments of the church, as the key to salvation or unity with God.

- They tended to deny the physical resurrection of Jesus, believing this event to be purely spiritual in nature.

- By the mid-second century, Chrisstian gnostics often believed that the God of the Jews was a different, lower being from the True God, having come into existence through the Fall of Sophia (see below).

Many gnostics, such as the Valentinians, were highly disciplined and ascetic. Others, however, were accused of teaching that gnosis liberates a person from moral constraint. Many believed in a doctrine known as docetism, the teaching that Jesus only appeared to possess a physical body. It was against this doctrine that 2 John 1:7 famously objects when it states:

- "Many deceivers, who do not acknowledge Jesus Christ as coming in the flesh, have gone out into the world. Any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist."

Various gnostic groups taught other doctrines which were rejected by the orthodox church, including:

- that God is androgynous (embracing both masculinity and feminity)

- that God himself is not a Trinity but a Unity

- that the Trinity which emerged from God is Father, Mother, and Son (or alternatively, that the Holy Spirit is feminine)

- that certain disciples (such as Thomas of Mary Magdalene) received special knowledge from Jesus, which withheld from less enlightened disciples such as Peter

- that spiritual knowledge is more important than sacraments such as Holy Communion

- that women can administer baptsim and act as priests

Some gnostics, in common with such Neoplatonic philosophers as Plotinus, held matter to be evil. However, others believed that matter is not evil in and of itself. Rather, it is a persons association with matter rather than spirit that leads one astray. Gnostics often taught a doctrine of the "bridal chamber," in which the human soul is reunited with God. In association with this idea, they were accused by orthodox Christians of engaging in licentious sexual rituals. Evidence from gnostic sources regarding this, however, is lacking. Indeed, many gnostic text portray not only an ascetic tradition, but even a rejection of sexuality for those seeking gnosis.

History

Early Jewish Gnosticism

Some scholars, notably Gershom Scholem, believe that Jewish gnosticism predated its Christian counterpart. There is indeed some evidence of Jewish mysticism in the pre-Christian era. This can be seen for exmaple in the philosophical writings of Philo of Alexandria, the revelations of Ezekiel (which produced a vast quantity of later kabbalistic speculation), the apocalyptic sections of the Book of Daniel, and detailed explanations about the angelic world in the apocyphal Book of Enoch. The latter certainly contributed to gnostic descriptions and names of the archons, aeons, etc. (See "Gnostic Cosmology" below.)

However, the data supporting a specifically gnostic Jewish worldview during this period is sparse. In later centuries, the works of the kabbalah clearly indicate a type of Jewish gnosticism. It has yet to be demonstrated, however, that this literature did not evolve out the interaction between gnostics and Jews in Europe during the middle ages, as many believe.

Christian tradition blames the Jewish (or Samaritan) "sorcerer" Simon Magus as the originator gnosticism. The Church Fathers described him as founding a gnostic sect that practiced antinomianism — the doctrine that moral laws did not apply to one who had attained salvation or enlightenment. According to the Book of Acts, this Simon was simply a magician whose sin was that he wanted to pay money so that he could obtain the power of the Holy Spirit for personal gain. It is impossible to say whether the actual Simon was an historical figure, let alone whether his teachings might have constituted a type of gnosticism, Jewish or otherwise.

Christian Gnosticism

Gnosticism can be viewed as one of the three main branches of early Christianity. The others are are Jewish Christianity, which was practiced by the disciples of Jesus; and orthodox Pauline Christianty, which rejected Jewish tradition but did not go as far as gnostic Christianity in adopting Hellenistic ideas.

For some time, Pauline Christianity and gnostic Christianity appear to have coexisted. Certain of Paul's letters teach concepts in accord with gnostic teaching — such as the struggle between the flesh and the spirit (Rom. 7:23), the superiority of the spiritual man over the man of flesh (Rom. 8:5), and the existence of secret spiritual teachings that could not be shared with immature Christians (1 Cor 3:1-2). So too, the gospels speak of gnostic themes such as Christ as a pre-existent being of light (John 1:3-5), the triumph of light over darkness, and the struggle of the spirit vs. the flesh. Gnostic teachers made great use both of Paul's letters as the gospels, especially Luke and John.

Later Christian scriptures appear to attack early gnosticism directly. For example:

- I Timothy 1:3-4 directs: "Stay there in Ephesus so that you may command certain men not to teach false doctrines any longer nor to devote themselves to myths and endless genealogies." The letter urges Timothy to "Turn away from godless chatter and the opposing ideas of what is falsely called knowledge (gnosis), which some have professed and in so doing have wandered from the faith. (6:20-21)

- The short Letter of Jude appears to have been written to warn of "certain men.. who have secretly slipped in among you. They are godless men, who change the grace of our God into a license for immorality..." (1:4) — a possible reference to gnostic teachers who went so far as to affirm that not only the Jewish kosher and circumcision laws, but also the Ten Commandements themselves held no authority over Christians.

Thus, various gnostic and semi-gnostic sects worked within mainline Christian groups. One such group has been named by contemporary scholars the "School of Thomas" — those who accepted the Gospel of Thomas and believed the resurrection to have been spiritual rather than physical.

An important second century semi-gnostic leader was Marcion, a mid-second century teacher who gained a signficant following in the church of Rome. Marcion accepted the gnostic proposition that the Hebrew Creator-God was actually the Demiurge described in gnostic literature, and thus a different being from the loving Heavenly Father of Jesus Christ. He proposed that the Old Testament scriptures should be rejected by Christians and accepted only the Gospel of Luke and the letters of Paul as authoritative. The church's rejection of Marcionism resulted in two important developements: Christianity's formal accpetance of the Jewish God as identical with the God of Christianity, and the church's recognition of both the Old Testament scriptures and a growing list of Christian works that eventually became the New Testament canon.

Valentinus, Basilides and the Sethians

The second century Christian gnostic teacher of widest renown was Valentinus, who was to found his own school of gnosticism in both Alexandria and Rome. According to Tertullian, Valentinus had been a significant figure in the Roman church at one time. He claimed to have received a revelation directly from the Logas, and also to have been instructed Theudas, who in turn had received secret knowledge passed on to him by the Apostle Paul. According to Irenaeus, Valentinus was the author of the Gospel of Truth.

Valentinus lived from about 100–175 C.E. While in Alexandria, where he was born, Valentinus probably would have had contact with another major gnostic teacher Basilides, and may have been influenced by him. The followers of Basilides can be viewed as forming a distinct sect from the Valentians, although their views in many ways overlapped.

Valentinian gnosticism flourished throughout the early centuries of the common era, and the group's Christian opponents make its vitality clear. A list or heretics composed in 388 C.E., against whom Emperor Constantine intended legislation, includes the Valentians. Valentinus' students elaborated on the teachings and materials they received from him. Several varieties of their central myth are known. (see "Gnostic Cosmology.")

Valentinian works probably make up a significant part of the Nag Hammadi library, although some analysts identify the collection's "Sethian" literature as coming from a separate gnostic sect, with similar teachings to Valentinus. Several other gnostic groups existed as well, although the evidence for them most from their opponents. For example, "Ophites" is a blanket term refering to various gnostic sects of this period. Included among them were both the Sethians and the Naasseners, the latter supposedly honoring the Demiurge, whom they identified with the serpent of Genesis, as a hero.

Manicheism

Manichaeism, a gnostic religion that originated in third century Babylon (a province of Persia at the time), reached, over the span of the next ten centuries, from North Africa to China. Named after its prophet, Mani, its teachings moved west into Syria, Northern Arabia, Egypt and North Africa, where the future Saint Augustine was a member of its school from 373-382. From Syria it progressed into Palestine, Asia Minor, and Armenia. There is evidence for Manicheans in Rome and Dalmatia in the foruth century, and also in Gaul and Spain. Many of the members of earlier Christian gnostic sects may have been dawn into its orbit.

Manicheanism was attacked by imperial edicts and polemical writings, but the religion remained strong in the western Roman Empire until the sixth century. In the east, Manicheanism was able to bloom. In the early years of the Arab conquest, Manicheanism again found followers in Persia and flourished especially in Central Asia, where it had spread through Iran. Here, in 762, Manicheanism became the state religion of the Uigar Empire.

Manichean gnosticism exerted an important later influence in the west through the emergence of the Paulicians, Bogomils and Cathari in the middle ages. The Cathari, also called Abigensians, controlled signifcant areas of Sourthern France during the 12th century. Through the Inquisition and the Abligensian Crusade, these gnostic movements were ultimately and ruthlessly stamped out as heresy by the Catholic Church.

Mandaeanism

A gnostic sect with ancient roots, Mandaeanism is still practised in small numbers, in parts of southern Iraq and the Iranian province of Khuzestan. The name of the group derives from the term: Mandā d-Heyyi which roughly means "Knowledge of Life." Although its exact chronological origins are not known, the group looks to John the Baptist as a central figure and teacher. Frequent ritual immersions and vegetarianism play a important part in Mandaean practice. Unlike Christian gnosticism, Mandaeanism rejects Jesus as teacher of truth, believing him to be false prophet who perverted the teachings of the Baptist.

Significant amounts of early Mandaean scripture survive in the modern era. The primary source text, known as the Genzā Rabbā, and has portions identified by some scholars as being copied as early as the second century C.E.. Also important as the Qolastā, or Canonical Book of Prayer and The Book of John the Baptist. The Mandaeans were serverely repressed under the regime of Saddam Hussein. As of 2006, they were technically a legal religion in Iraq, but reported significant persecution by non-governmental forces, especially Shiite Muslims, who consider them to be pagan infidels rather than "People of the Book.'

Gnostic Cosmology

By the late second century, the gnostic movement had developed a rather involved cosmology. Although it varied widely and should not oversimplified, a basic outline can be useful for our understanding:

Creation

The "classical" gnostic mythology posits a sort of prologue to the Judeo-Christian version of creation as described in the Book of Genesis. It speaks of an unknown God, defined as immovable, invisible, intangible, and ineffable. God is seen as being androgynous, both male and female, and "all-containing" or sometimes "the uncontained." God may also be referred to as the Monad, or the first Aeon. In gnosticism, God cannot be accurately described in any positive sense through words; it is more possible to say what God isn't. It is only in experiencing God through gnosis that the Deity can be truly understood — but this, too, defies verbal description.

- He did not lack anything, that he might be completed by it; rather he is always completely perfect in light. He is illimitable, since there is no one prior to him to set limits to him. He is unsearchable, since there exists no one prior to him to examine him. He is immeasurable, since there was no one prior to him to measure him. He is invisible, since no one saw him. He is eternal, since he exists eternally. He is ineffable, since no one was able to comprehend him to speak about him. He is unnameable, since there is no one prior to him to give him a name. He is immeasurable light, which is pure, holy, immaculate. He is ineffable, being perfect in incorruptibility. (He is) not in perfection, nor in blessedness, nor in divinity, but he is far superior. He is not corporeal nor is he incorporeal. He is neither large nor is he small. There is no way to say, 'What is his quantity?' or, 'What is his quality?', for no one can know him.

This original God went through a series of emanations, during which its essence is seen as expanding into many successive "generations" of paired male and female beings, called "aeons." Some gnostic texts posit 15-30 such pairs (probably the "endless genealogies" refered to in 2 Timothy, above). These can also be seen as representative of the various attributes of God. Collectively, God and the aeons comprise the sum total of the spiritual universe, known as the Pleroma. One of the first of the aeons was the feminine counterpart of God.

- His thought performed a deed and she came forth, namely she who had appeared before him in the shine of his light... the perfect glory in the aeons, the glory of the revelation, she glorified the virginal Spirit and it was she who praised him, because thanks to him, she had come forth. This is the first thought, his image. She became the womb of everything, for it is she who is prior to them all, the Mother-Father, the first man, the holy Spirit, the thrice-male, the thrice-powerful, the thrice-named androgynous one, and the eternal aeon among the invisible ones, and the first to come forth.

In some versions of the myth, one of the first aeons was Christos, or Christ, who was later sent to earth as the savior. In others, Christ appears to embody several of the characteristics of the first aeons. One Valentinian list (the genealogies vary quite significantly) list identifies the following generations of aeons:

First generation: Bythos or the Monad (the One)

Second generation: Caen (Power) and Akhana (Love)

Third generation, emanated from Caen and Akhana: Nous (Nus, Mind) and Aletheia (Veritas, Truth)

Fourth generation, emanated from Nous and Aletheia: Sermo (the Word) and Vita (the Life)

Fifth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita: Anthropos (Humanity) and Ecclesia (Church)

Sixth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita: Bythios (Profound) and Mixis (Mixture), Ageratos (Never old) and Henosis (Union), Autophyes (Essential nature) and Hedone (Pleasure), Acinetos (Immovable) and Syncrasis (Commixture), Monogenes (Only-begotten) and Macaria (Happiness); emanated from Anthropos and Ecclesia: Paracletus (Comforter) and Pistis (Faith), Patricas (Paternal) and Elpis (Hope), Metricos (Maternal) and Agape (Love), Ainos (Praise) and Synesis (Intelligence), Ecclesiasticus (Son of Ecclesia) and Macariotes (Blessedness), Theletus (Perfect) and Sophia (Wisdom).

At this point in the gnostic cosmology, the universe was still entirely non-material. However, the emanations of God into increasing numbers of aeons led, eventually, to potential instability within the primordial universe. This reached a critical point with the appearance of the aeon most distant from the origin, Sophia (Greek for "wisdom").

Fall

Sophia's distance from the Original One produced a sense of anxiety and fear of losing her life, as well as confusion and longing to return to God. In some versions of the myth, Sophia attempts to surmount the rigid hierarchy of the divine nature, in order to approach close to God. In other versions, she imitates God by performing an emanation of her own. In both cases, this intransigence causes a crisis within the Pleroma, leading to the creation of the Demiurge.

In the Apocryphon of John, the Demiurge is referred to as Yaldabaoth, a "serpent with a lion's head."

- "And when she saw (the consequences of) her desire, it changed into a form of a lion-faced serpent. And its eyes were like lightning fires which flash. She cast it away from her, outside that place, that no one of the immortal ones might see it, for she had created it in ignorance. — Apocryphon of John

Sophia hides the Demiurge, but he later escapes. The Demiurge then creates the physical world in which we live. To assist in the completion of his task, the Demiurge spawns a group of entities known collectively as Archons — the demigods and craftsmen of the physical world.

At this point, the events of the gnostic narrative join with the events of Genesis, with the Demiurge and his cohorts fulfilling the role of the Creator and his angels. The Demiurge declares himself to be the only god, and that none exist superior to him. Thus, humankind became trapped a the Demiurge's web of material illusion, cut off from the true God and source of divine light.

Redemption

Regreting her action, Sophia managed to infuse a spiritual spark or pneuma into the Demiurges creation. The savior (who is the Aeon Christos) comes to Sophia and allows her to see the light again. Christos and Sophia, in some version of the myth, work together to reawaken humans to the Truth. While Sophia remains in the Pleroma, Christos descends to earth in the form of the man Jesus to give men the gnosis they need to rescue themselves from the physical world and return to spiritual reality.

Three types of humans responsd differently to Christ's message. These types reflect the three sensations experienced by Sophia:

- hylics (bound to the matter, the principle of evil)

- psychics (bound to the soul and partly saved from evil)

- pneumatics, free to return to the Pleroma if they achieve gnosis

Thus Sophia, despite her negative role in the tragedy of creation, plays a positive role in relation to helping humankind to reawaken from "forgetfulness" into the light of truth. In some cases she is even seen as the spiritual consort or female counterpart of Christ:

- The perfect Savior said: "The Son of Man consented with Sophia, his consort, and revealed a great androgynous light. His male name is designated 'Savior, Begetter of All Things'. His female name is designated 'All-Begettress Sophia'. Some call her 'Pistis' (faith). — The Sophia of Jesus

Some gnostics not only rejected the Jewish God as the Demiurge, but consequently reinterpreted biblical stories so that the enemy of this god's tyranny became a hero. Thus, many gnostics regarded the serpent in the Garden of Eden as a messenger of light who could help humanity free itself of the chains of the Demiurge, or Yaldabaoth. In this version of the myth, Sophia gives wisdom to humankind by way of the serpent, opening the way to gnosis. This angered the Demiurge, who believed himself to be the sole creator of the universe and the exclusive ruler of this world.

In some versions of the story, Seth, the third son of Adam, was introduced to the gnostic teachings by both his father and/or his mother, and this knowledge has been preserved throughout the genrations. Several of the gnostic writings discovered at Nag Hammadi take the form of revelations from Seth, Adam, Jesus or one of the disciples.

Gnostic texts

Note that like everything else about Gnosticism, the identification of a text as Gnostic or not may be controversial, however most Nag Hammadi codices may be assumed to be Gnostic in essence, except for the copy of Plato and the "sayings" Gospel of Thomas.

- Gnostic Works recovered before 1945:

- Works preserved by the Church:

- Acts of Thomas (Especially The Hymn of the Pearl and The Hymn of the Robe of Glory)

- The Acts of John (Especially The Hymn of Jesus)

- The Askew Codex (British Museum, bought in 1784):

- Pistis Sophia: Books of the Savior

- The Bruce Codex (discovered by James Bruce):

- The Gnosis of the Invisible God or The Books of Jeu

- The Untitled Apocalypse or The Gnosis of the Light

- The Berlin Codex or The Akhmim Codex (found in Akhmim, Egypt):

- The Gospel of Mary

- The Acts of Peter

- The Wisdom of Jesus Christ

- Unknown origin:

- The Secret Gospel of Mark

- The Hermetica

- Works preserved by the Church:

- The Nag Hammadi library found in December 1945. (Follow the link to Nag Hammadi library for a complete list.)

Gnosticism in modern times

... modern gnosticism has continued to develop, from origins in the Occultism of the 19th century. Thus "gnosticism" is also applied to many modern sects where only initiates have access to arcana. However, there has always been a great deal of diversity within gnosticism and modern gnostic doctrines sometimes have little to do with ancient gnosticism; the application of the antiquated term to these distinctly modern movements, far from being a clarification of the nature of gnosticism, further occludes its true nature.

Gnosticism has been treated at length by several modern authors, philosophers and psychologists:

- William Blake, the nineteenth century Romantic poet and artist, was according to some sources well-versed in the doctrines of the Gnostics, and his own personal mythology contains many points of cohesion with several Gnostic myths (for example, the Blakean figure of Urizen bears many resemblances to the Gnostic Demiurge). However, efforts to dub Blake a "Gnostic" have been complicated by the complex nature and extent of Blake's own mythology, and the variety of myths and themes that may be referred to as "Gnostic"; thus, the exact relationship between Blake and the Gnostics remains a point of scholarly contention, though a comparison of the two often reveals intriguing points of cohesion.

- After a series of visions and archival finds of Cathar-related documents, Jules Doinel "re-established" the Gnostic Church in the modern era. Founded on extant Cathar documents with a heavy influence of Valentinian cosmology, the church, officially established in the autumn 1890 in Paris, France, consisted of modified Cathar rituals as sacraments, a clergy that was both male and female, and a close relationship with several esoteric initiatory orders (see link http://www.gnostique.net for more information). The church eventually split into two opposing groups that were later reconciled in the leadership of Joanny Bricaud. Another splinter church with more occult leanings was established by Robert Ambelain around 1957, from which several other schisms have produced a multitude of distantly-related occult-oriented marginal groups.

- The "traditionalist" René Guénon founded in 1909 the Gnostic review La Gnose. He believed in and throughout his works exposed the idea that modern thought, by its preference to the quantity more than to the quality, is the root of all evil aspects of modernity. The whole scientific enterprise would just be the beheaded relic of a lost Sacred Science. Modern technology and its realizations, worshipped by his contemporaries, would have been just a latter epiphany of the Kali Yuga (alias Dark Age), in a Cyclical Conception of Time.

- Carl Jung and his associate G. R. S. Mead worked on trying to understand and explain the Gnostic faith from a psychological standpoint. Jung's "analytical psychology" in many ways schematically mirrors ancient Gnostic mythology, particularly those of Valentinus and the "classic" Gnostic doctrine described in most detail in the Apocryphon ("Secret Book") of John. Jung understands the emergance of the Demiurge out of the original, unified monadic source of the spiritual universe by gradual stages to be analogous to (and a symbolic depiction of) the emergence of the ego from the unconscious. However, it is uncertain as to whether the similarities between Jung's psychological teachings and those of the Gnostics are due to their sharing a "perennial philosophy", or whether Jung was unwittingly influenced by the Gnostics in the formation of his theories; Jung's own "Gnostic sermon", the Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, would tend to imply the latter. Uncertain too are Jung's claims that the Gnostics are aware of any psychological meaning behind their myths. On the other hand, what is known is that Jung and his ancient forebears disagreed on the ultimate goal of the individual: whereas the Gnostics clearly sought a return to a supreme, other-worldly Godhead, Jung would see this as analogous to a total identification with the unconscious, a dangerous psychological state.

- Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy enjoyed and wrote extensively on Gnostic ideas.

- The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in his concept of the "eternal return".

- The philosopher Hans Jonas wrote extensively on Gnosticism, interpreting it from an existentialist viewpoint.

- Eric Voegelin identified a number of similarities between ancient Gnosticism and those held by a number of modernist political theories, particularly Communism and Nazism. He identifies the root of the Gnostic impulse as alienation, that is, a sense of disconnectedness with society and a belief that this lack of concord with society is the result of the inherent disorderliness or even evil of the world. This alienation has two effects. The first is the belief that the disorder of the world can be transcended by extraordinary insight, learning, or knowledge, called a Gnostic Speculation by Voegelin. The second is the desire to implement a policy to actualize the speculation, or as Voegelin describes to "Immanentize the Eschaton", to create a sort of heaven on earth within history. The totalitarian impulse is derived from the alienation of the proponents of the policy from the rest of society. This leads to a desire to dominate (libido dominandi) which has its roots not just in the conviction of the imperative of the Gnostic's vision but also in his lack of concord with a large body of his society. As a result, there is very little regard for the welfare of those in society who are impacted by the resulting politics, which ranges from coercive to calamitous (cf. Stalin's nostrum: "You have to crack a few eggs to make an omelet"). This totalitarian impulse in modernism has been noted by Catholic writers, particularly in Henri de Lubac's work "The Drama of Atheist Humanism", which explores the connection between the totalitarian impulses of political Communism, Fascism and Positivism with their philosophical progenitors Hegel, Feuerbach, Marx, Comte and Nietzsche. Indeed, Voegelin acknowledges his debt to this book in creating his seminal essay "Science, Politics, and Gnosticism". The Catholic catechism makes an oblique reference to the desire to "Immanentize the Eschaton" in article 676: The Antichrist's deception already begins to take shape in the world every time the claim is made to realize within history that messianic hope which can only be realized beyond history through the eschatological judgment. The Church has rejected even modified forms of this falsification of the kingdom to come under the name of millenarianism, especially the "intrinsically perverse" political form of a secular messianism. Other Catholic scholars have extended it using vivid imagery created by Abbé Augustin Barruél.

- Samael Aun Weor commented extensively on the Pistis Sophia in his book The Pistis Sophia Unveiled, and founded International Gnostic Movement, one of the Occultist movements that claimed inheritance from ancient Gnosticism.

- In the United States there are several gnostic churches with diverse lineages, one of which is the Ecclesia Gnostica, affiliated with an organization for studies of gnosticism named the Gnostic Society, primarily in Los Angeles. The current leader of both organizations is Stephan A. Hoeller who has also written extensively on Gnosticism and the occult.

- Aleister Crowley's Thelema system is influenced by and bears major features in common with Gnosticism, especially in that adherants work to come to their own direct knowledge of the divine (referred to as the Great Work). There are several Thelemic Gnostic organizations, including Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica as an ecclesiastical body and Ordo Templi Orientis as an initiatory body.

- Mar Didymos of the Thomasine Church has reinterpreted Gnosticism and the thomasine gospels from an Illuminist viewpoint. The method employed by clergy and initiates of the Thomasine Church involves the use of the scientific method and of critical thinking rather than dogmatism. Mar Didymos stresses the use of scientific theory or the use of a synthesis of well developed and verified hypotheses derived from empirical observation and deductive/indicative reasoning about factual data and tested through experimentation and peer review. This is antithetical in principle and method as compared to all of the existing modern Gnostic churches.

- Mar Iohannes of the Apostolic Johannite Church is President of the North American College of Gnostic Bishops, a group dedicated not to dogmatic statements, but to working together to promote gnostic growth. The AJC is a bridge-building Church with traditionally-styles Rites, but Gnostic understanding of those Rites. 'Experiential Knowledge' of the Divine is the final arbiter of Gnosis.

Gnosticism in popular culture

Gnosticism has also seen something of a resurgence in popular culture in recent years.

- Grant Morrison's comic series The Invisibles draws on Gnostic mythemes, both in terms of overall structure and through occasional direct reference. Morrison's other works, such as Animal Man and The Filth, also possess frequent moments of structural cohesion with Gnostic worldviews, though these make no direct reference.

- Alan Moore, acclaimed writer of From Hell, Watchmen, V for Vendetta and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, converted to Gnosticism in the late 1990s. His work, like that of the Gnostics, demonstrates a keen interest with the often-ambivalent relationship between subject and reality, consciousness (especially altered and enlightened states of consciousness) and revolt against constrictive systems of control. In Watchmen, one character who hatches a monstrous plot to save the world might be said to be subscribe to Gnosticism much as Voegelin describes the phenomenon.

- Anatole France's novel The Revolt of the Angels (La Revolte des Anges) weaves the story of an unhappy guardian angel and the doctrine of Yaldabaoth, to satiric effect.

- Several works of science fiction author Philip K. Dick draw on various gnostic notions, especially his late novel Valis and The Divine Invasion.

- Robert Charles Wilson's work has gnostic themes to it, particularly overt in his novel Mysterium (1994).

- Allen Ginsberg uses several Gnostic terms in his poem Plutonian Ode.

- Harold Bloom explores Gnosticism in his novel The Flight to Lucifer: A Gnostic Fantasy, and, with William Golding, traces Gnosticism in American beliefs in The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation. Another work of Bloom's - Genius, in which he reviews 100 literary figures and identifies their own peculiar genius - makes introductory reference to Gnosticism as "the religion of literature".

- Some conspiracy theories have Gnostic overtones. (Much due to Eric Voegelin.)

- Such films as Dark City, Pleasantville, The Matrix, The Truman Show, Twelve Monkeys, Groundhog day, Vanilla Sky and even Toy Story can be compared to Gnosticism because they present the idea that the world we perceive is an illusion created by someone who does not love us, and that the key to unravelling this illusion and perceiving reality (often this perception is concurrent to a "return" to reality) resides in a form of self-knowledge or enlightenment.

- Philip Pullman's trilogy His Dark Materials draws heavily on Gnostic themes.

- The role playing game Kult is also based on Gnostic ideas, as is the MTV animated science fiction television series, Æon Flux.

- Gnosticism figures heavily in the Jesus Mysteries Thesis of Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy.

- The authors Umberto Eco, Emile Cioran and Jorge Luis Borges are heavily inspired by gnosticism. In the case of the former, this is particularly evident in two novels: Foucault's Pendulum and Baudolino. In the latter novel, one character describes the Gnostic creation myth at length.

- The role-playing games Final Fantasy VII and X, Chrono Trigger, Chrono Cross, and Xenogears by Squaresoft as well as the Xenosaga series now in the hands of an ex-Square team known as Monolith Soft contain subtle, if not outright (as in the case of Xenosaga), themes of and references to Gnosticism.

- Dan Brown's bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code draws on Gnostic scriptures and modern re-interpretations of those works as well as a pseudohistory of christian faiths along the lines of Holy Blood, Holy Grail'.

- In her book "The Secret Magdalene", the writer Ki Longfellow explores the birth of gnosticism in her novel treatment of the life of Mary Magdalene, as well as in the life of Jesus - contending that both experienced "gnosis", which is also called "Christ Consciousness" as well as "Enlightenment".

- In her book "Piece By Piece", the musician Tori Amos explores the influences and experiences in her life that have shaped her musical compositions. In the first two chapters she explores the Gnostic belief that Mary Magdalene wrote the 4th Gospel of the apostles, this research would have a profound impact on her 2005 work The Beekeeper.

- In the Marvel Comics universe, the origins of the Earth are described using Gnostic conventions, specifcally the Demiurge as the creator of the universe, and other ideas. This view of the creation of the Marvel earth was expounded upon in the back-up features of the 1989 Annual issues of their comics, all part of the "Atlantis Attacks" crossover.

See also

- Abraxas

- Apocrypha

- Agnosticism

- Christian theosophy

- Christian Meditation

- First Council of Nicaea

- Gospel

- Zoroastrianism

- Esoteric Christianity

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Books

Primary sources

- Robinson, James (1978). The Nag Hammadi Library. . ISBN 0-06-066934-9. (549 pages)

Secondary sources

- Aland, Barbara (1978). Festschrift für Hans Jonas. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-58111-4.

- Freke, Timothy and Gandy, Peter (1999). The Hermetica: The Lost Wisdom of the Pharaohs. Tarcher. ISBN 0874779502.

- Freke, Timothy and Gandy, Peter (2002). Jesus and the Lost Goddess : The Secret Teachings of the Original Christians. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-00-710071-X.

- Haardt, Robert (1967). Die Gnosis: Wesen und Zeugnisse. Müller. . (352 pages)

- Hoeller, Stephan A. (2002). Gnosticism - New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing. . ISBN 0-8356-0816-6. (257 pages)

- Jonas, Hans (). Gnosis und spätantiker Geist vol. 2:1-2, Von der Mythologie zur mystischen Philosophie. . ISBN 3-525-53841-3.

- King, Karen L. (2003). What is Gnosticism?. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01071-X. (343 pages)

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (1993). Gnosis on the Silk Road: Gnostic Texts from Central Asia. Harper, San Francisco. ISBN 0-06-064586-5.

- Layton, Bentley, edited by L. Michael White, O. Larry Yarbrough (1995). Prolegomena to the study of ancient gnosticism (in The Social World of the First Christians: Essays in Honor of Wayne A. Meeks). Fortress Press, Minneapolis. ISBN 0800625854.

- Longfellow, Ki (2005). The Secret Magdalene. . ISBN 0-9759255-3-9. (458 pages)

- Pagels, Elaine (1979). The Gnostic Gospels. . ISBN 0679724532. (182 pages)

- Pagels, Elaine (1989). The Johannine Gospel in Gnostic Exegesis. . ISBN 1555403344. (128 pages)

- Williams,Michael (1996). Rethinking Gnosticism: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691011273.

Audio lectures

- BC Recordings - Offers an excellent and extensive collecton of downloadable MP3 lecture by Stephan A. Hoeller on Gnosticism.

Videos

- The Naked Truth - Exposing the Deceptions About the Origins of Modern Religions (1995) ASIN: 1568890060

External links

Ancient Gnosticism

- Gnostic Society - multiple texts on Gnosticism and a bibliography of secondary reading

- Early Christian Writings - primary texts

- Introduction to Gnosticism

- Religious Tolerance - A survey of Gnosticism

- Catholic Encyclopedia Entry

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Gnosticism

- Proto-gnostic elements in the Gospel according to John - Article in Theandros

- Gnosticweb - Article: Gnosis Through the Ages, Early Christian Gnostic texts to download.

Modern Gnosticism

- Apostolic Johannite Church

- Ecclesia Gnostica

- French Gnostic Tradition (i.e. Doinel, et al.)

- The North American College of Gnostic Bishops

- Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica Hermetica

- Eglise du Plérôme - Cathar/Valentinian

- Church of Gnosis (Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum)

- The Gnostic Friends Network

- Thomasine Church

- Gnosticweb Samael Aun Weor group.

- The Gnostic Movement Samael Aun Weor group.

- Mysticweb Samael Aun Weor group.

Gnosticism in popular culture

- Frances Flannery-Dailey & Rachel Wagner, Wake Up! - Gnosticism & Buddhism in The Matrix, an essay on Gnostic and Buddhist influences on The Matrix.

- Geoff Klock, X-Men, Emerson, Gnosticism, an essay discussing Gnostic influences on The X-Men.

Gnostic blogs

- inTerjeCted, weblog of Norwegian Gnostic Terje Bergersen

- fantastic planet, blog featuring Gnostic philosophy on events political, fortean and otherwise interesting

- Ecclesia Gnostica in Nova Albion, blog of Jordan Stratford, a priest in The Apostolic Johannite Church

- Homoplasmate, "A forum for the discussion of Gnosticism and Gnostic Christianity"

- Ecclesiastical Gnosis-Personal Reflections, weblog of Bishop Shaun McCann of The Apostolic Johannite Church

- Enormous Fictions: A website exploring Gnosticism, creativity, culture and various other ideas

Discussion groups and email lists

- gnosticism2 - Learn the history and ideas of Gnostics

- eglisegnostique - Eglise Gnostique, share information, discuss issues, network

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.