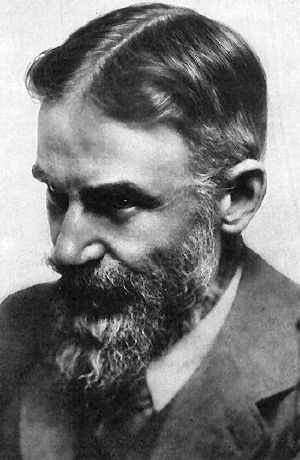

George Bernard Shaw

(George) Bernard Shaw[1] (July 26, 1856 – November 2, 1950) was an Irish-British playwright and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925 and the Academy Award in 1938 for Pygmalion. After those of William Shakespeare, Shaw's plays are some of the most widely produced in English language theatre.[citation needed]

Life

Born at 33 Synge Street in Dublin, Ireland to rather poor Church of Ireland parents, Shaw was educated at Wesley College, Dublin and moved to London during the 1870s to embark on his literary career. He wrote five novels, none of which were published, before finding his first success as a music critic on the Star newspaper. He wrote his music criticism under the pseudonym Corno di Bassetto.

In the meantime he had become involved in politics, and served as a local councillor in the St Pancras district of London for several years from 1897. He was a noted socialist who took a leading role in the Fabian Society.[2]

From 1895 to 1898, Shaw was the drama critic of the Saturday Review.[citation needed] In 1898, he married an Irish heiress, Charlotte Payne-Townshend.

Shaw completed his first play, Widower's Houses, in 1892. He would write over 50 plays, most of them full-length. Many of his earliest works had to wait years to receive major productions in London, but they are still being performed today. Among them are Mrs. Warren's Profession (1893), Arms And The Man (1894), Candida (1894) and You Never Can Tell (1895).

His first financial success as a playwright came from Richard Mansfield's American production of The Devil's Disciple (1897). Shaw became a popular playwright in America and Germany before he was so in London.

His plays at this point tend to become less compact, talkier, but no less successful. These works include Caesar And Cleopatra (1898), Man And Superman (1903), Major Barbara (1905) and The Doctor's Dilemma (1906). From 1904 to 1907, several of his plays had their London premieres in notable productions at the Court Theatre, managed by Harley Granville-Barker and J.E. Vedrenne.

His first original play performed at the Court, John Bull's Other Island (1904), was a piece about Ireland. Though not one of his more popular plays today, more than any other it made his reputation in London when, during a command perfomance for King Edward VII, the King laughed so much he broke his chair.

By the 1910s, Shaw was a well-established playwright. New works such as Fanny's First Play (1911) and Pygmalion (1913) – which My Fair Lady was based on – had long runs in front of large London audiences.

Shaw opposed World War I and became unpopular with many of his fellow citizens. His work after the War was, in general, darker, though still full of the Shavian wit. His first full-length play after the war, written mostly during it, was Heartbreak House (1919). In 1923, he completed Saint Joan (1923), a play that brought him international fame and led to his Nobel Prize in Literature.

He continued writing plays for the rest of his life, but very few of them are as notable—or as often revived—as his earlier work. Probably his most popular work of this era was The Apple Cart (1929). His last full-length work was Bouyant Billions, (1947), written when he was in his nineties.

Many of Shaw's published plays come with lengthy prefaces. These tend to be essays more about Shaw's opinions on the issues dealt with in the plays than about the plays themselves. Some prefaces are much longer than the actual play. For example, the Penguin edition of his one-act The Shewing-up Of Blanco Posnet (1909) has a 67-page preface for the 29-page piece.

Shaw died in 1950 at the age of 94 due to a fall from a ladder.[3]

After his death

By the time of his death, Shaw was not only a household name in Britain, but a world figure. His ironic wit endowed the language with the adjective "Shavian" to refer to such clever observations as "England and America are two countries divided by a common language."[4]

From 1906 until his death, Shaw lived at Shaw's Corner in the small village of Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire. The house is now a National Trust property, open to the public.

Concerned about the inconsistency of English spelling, he willed a portion of his wealth to fund the creation of a new phonemic alphabet for the English language. On his death bed, he did not have much money to leave, so no effort was made to start such a project. However, his estate began to earn significant royalties from the rights to Pygmalion when My Fair Lady, a musical adapted from the play by his comrade film producer Gabriel Pascal, became a hit. It then became clear that the will was so badly worded that the relatives had grounds to challenge the will, and in the end an out-of-court settlement granted only a small portion of the money to promoting a new alphabet. This became known as the Shavian alphabet. The National Gallery of Ireland, RADA and the British Museum all received substantial bequests.

The Shaw Theatre, Euston Road, London was opened in 1971 and named in his honour.

The Shaw Festival, an annual theater festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, began as an eight week run of Don Juan in Hell and Candida in 1962 and has grown into an annual festival with over 800 performances a year, dedicated to producing the works of Shaw and his contemporaries.

Friends and correspondents

Shaw, in his lifetime, maintained correspondence with hundreds of personages, many notable and many not.[citation needed] His letters to and from Mrs. Patrick Campbell were adapted for the stage by Jerome Kilty as Dear Liar: A Comedy of Letters; as was his correspondence with the poet Lord Alfred 'Bosie' Douglas (the intimate friend of Oscar Wilde), into the drama Bernard and Bosie: A Most Unlikely Friendship by Anthony Wynn. His letters to the prominent actress, Ellen Terry, the boxer Gene Tunney, and H.G. Wells have also been published.

Shaw campaigned against the executions of the rebel leaders of the Easter Rising, and he became a personal friend of the Cork-born IRA leader Michael Collins, whom he invited to his home for dinner while Collins was negotiating the Anglo-Irish Treaty with Lloyd-George in London. After Collins's assassination in 1922, Shaw sent a personal message of condolence to one of Collins's sisters.

Shaw had a long time friendship with G. K. Chesterton, the Catholic-convert British writer, and there are many humorous stories about their complicated relationship.

Another great friend was the composer Edward Elgar.[citation needed]

Shaw's correspondence with the motion picture producer Gabriel Pascal, who was the first to successfully bring Shaw's plays to the screen and who later adapted Pygmalion into "My Fair Lady," is published in a book titled Bernard Shaw and Gabriel Pascal (ISBN 0802030025).

A stage play based on a book by Hugh Whitemore, The Best of Friends, provides a window on the friendships of Dame Laurentia McLachlan, OSB (late Abbess of Stanbrook) with Sir Sydney Cockerell and Shaw through adaptations from their letters and writings.

Socialism and political beliefs

Shaw had a vision (letter to Henry James of January 17, 1909):

- “I, as a Socialist, have had to preach, as much as anyone, the enormous power of the environment. We can change it; we must change it; there is absolutely no other sense in life than the task of changing it. What is the use of writing plays, what is the use of writing anything, if there is not a will which finally moulds chaos itself into a race of gods.”

Shaw held that each class worked towards its own ends, and that those from the upper echelons had won the struggle; for him, the working class had failed in promoting their interests effectively, making Shaw highly critical of the democratic system of his day. The writing of Shaw, such as his plays Major Barbara and Pygmalion, has a background theme of class struggle.

Shaw's second career — after the theatre — was in support of socialism. In 1882 Henry George’s lecture on land nationalization gave depth and direction to Shaw’s political ideology. Shortly thereafter he applied to join the Social Democratic Federation. Its leader H. M. Hyndman introduced him to the works of Karl Marx. Instead, in May of 1884 he joined the newly-formed Fabian Society. He played a pivotal role with the Fabian Society and wrote a number of their pamphlets. He argued that property was theft and for an equitable distribution of land and capital. He was involved with the formation of the Labour Party. For a clear statement of his position[citation needed] read The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism, and Fascism.

Despite the fact that he identified as being a democratic socialist, in the 1930s Shaw approved of the regime of Stalin and also made some ambiguous statements that are often interpreted[citation needed] as being pro-Hitler. In 1945, his preface to the play Geneva staked a claim that the majority of the victims of the Nazi extermination camps had in fact died of "overcrowding". However, he also stated that Hitler had become a "mad messiah" over time. Shaw contrasted this with the situation in the Soviet Union where, according to Shaw, "Stalin... made good by doing things better and much more promptly than parliaments". Shaw also made numerous anti-semitic comments at this time, although the extent to which he was merely being ironic or provocative is unclear.

Vegetarianism

Bernard Shaw was a noted vegetarian. The following was taken from the archives of The Vegetarian Society UK[5]:

- The Summer of 1946 seems to have been a season of anniversaries and memorials. The Vegetarian Society itself was looking forward to its 100th anniversary and giving its members advance warnings of celebratory plans.

- But the big story of the July issue of The Vegetarian Messenger was the tribute to George Bernard Shaw, celebrating his 90th birthday on the 26th of that month. He had, at that time, been a vegetarian for 66 years and was commended as one of the great thinkers and dramatists of his era. "No writer since Shakespearean times has produced such a wealth of dramatic literature, so superb in expression, so deep in thought and with such dramatic possibilities as Shaw." The writer was a staunch vegetarian, anti-vivisectionist and opponent of cruel sports.

Sesquicentennial Anniversary of Birth

A programme of readings, guided tours and performances take place at 33 Synge Street, Dublin, the place of Shaw's birth, between July 22 and 29 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of his birth which is on July 26 2006. The National Gallery of Ireland, which regards Shaw as a generous benefactor, will have a series of celebratory festivities for the remainder of 2006. Several conferences are to be held across the globe and there will be theatre readings of all 52 Shaw plays.

Trivia

- Shaw was a motorcyclist, and gave TE Lawrence a Brough Superior.[citation needed]

- Upon visiting America, Shaw called New York Giants baseball manager John McGraw the "one true American"[citation needed].

- Shaw is the only person ever to have won both a Nobel Prize and an Academy Award.

- Shaw referred to Prophet Muhammad as the "Savior of Humanity" when he stated:

- "He must be called the Savior of Humanity. I believe that if a man like him were to assume the dictatorship of the modern world, he would succeed in solving its problems in a way that would bring it much needed peace and happiness."[6]

Works

Drama

|

|

Novels

- Immaturity (1879)

- The Irrational Knot 1880

- Love Among the Artists (1881)

- Cashel Byron's Profession (1882-83)

- An Unsocial Socialist (1883)

Essays

- Commonsense about the War

- The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism

- The Black Girl in Search of God

- Everybody's Political What's What? 1944 Constable

Music criticism

- The Perfect Wagnerite: A Commentary on the Niblung's Ring, 1923

Debate

- Shaw V. Chesterton, a debate between George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton 2000 Third Way Publications Ltd. ISBN 0953507777

References and footnotes

- ↑ Shaw never used his first name "George" personally or professionally: he was "Bernard Shaw" throughout his long career. Since his death it has become customary to use all three of his names, even in reference works.

- ↑ Holroyd, M, Bernard Shaw, London : Vintage, 1998,. ISBN 0099749017

- ↑ http://www.english.upenn.edu/~cmazer/mis1.html

- ↑ http://www.worldandi.com/newhome/public/2003/may/bkpub.asp

- ↑ http://www.ivu.org/history/shaw/index.html

- ↑ (1936) The Genuine Islam, Singapore, Vol. 1, No. 8.

See also

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- Comedy on screen

External links

- Works by George Bernard Shaw. Project Gutenberg

- "Excerpt from Caesar and Cleopatra" Creative Commons audio recording.

- Dan H. Laurence/Shaw Collection in the University of Guelph Library, Archival and Special Collections, holds more than 3,000 items related to his writings and career

- George Bernard Shaw at the Internet Movie Database

- Michael Holroyd. "Send for Shaw, not Shakespeare", The Times Literary Supplement, July 19, 2006.

- Sunder Katwala. "Artist of the impossible", Guardian Comment is Free, July 26, 2006.

- The Shaw Society

- The Bernard Shaw Society, New York

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.