Difference between revisions of "Gene" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

In 1941, George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum showed that mutations in genes caused errors in certain steps in metabolic pathways. This showed that specific genes code for specific proteins, leading to the "one gene, one enzyme" hypothesis. Oswald Avery, Collin Macleod, and Maclyn McCarty showed in 1944 that DNA holds the gene's information. In 1953, James D. Watson and Francis Crick demonstrated the molecular structure of [[DNA]]. Together, these discoveries established the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that proteins are translated from [[RNA]] which is transcribed from DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription in [[retrovirus]]es. | In 1941, George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum showed that mutations in genes caused errors in certain steps in metabolic pathways. This showed that specific genes code for specific proteins, leading to the "one gene, one enzyme" hypothesis. Oswald Avery, Collin Macleod, and Maclyn McCarty showed in 1944 that DNA holds the gene's information. In 1953, James D. Watson and Francis Crick demonstrated the molecular structure of [[DNA]]. Together, these discoveries established the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that proteins are translated from [[RNA]] which is transcribed from DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription in [[retrovirus]]es. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Evolution and genes== |

| − | |||

| − | + | Broadly defined, [[evolution]] is any heritable change in a population of organisms over time. Evolutionary changes are those that are inheritable via the genetic material. As noted by Curtis & Barnes (1989) "The changes in populations that are considered evolutionary are those that are inheritable via the genetic material from one generation to another." As such, evolution can also be defined in terms of allele frequency, with allele being alternative forms of a gene, such as an allele for blue eye color versus brown eye color. | |

| − | === | + | Two important and popular evolutionary theories that address the pattern and process of evolution are the [[Evolution#Theory of descent with modification|Theory of descent with modification]] and the [[Evolution#Theory of natural selection|theory of natural selection]]." The theory of descent with modification, or the "theory of common descent" deals with the pattern of evolution and essentially postulates that all organisms have descended from common ancestors by a continuous process of branching. The "theory of modification through natural selection," or the "theory of natural selection," deals with mechanisms and causal relationships, and offers one explanation for how evolution might have occurred— the process by which evolution took place to arrive at the pattern. |

| − | The genes that exist today are those that have reproduced successfully in the past. Often, many individual organisms share a gene; thus, the death of an individual need not mean the extinction of the gene. Indeed, if the sacrifice of one individual enhances the survivability of other individuals with the same gene, the death of an individual may enhance the overall survival of the gene. This is the basis of the selfish gene view, popularized by Richard Dawkins. He points out in his book, ''The Selfish Gene'', that to be successful genes need have no other "purpose" than to propagate themselves, even at the expense of their host organism's welfare. A human that behaved in such a way would be described as "selfish," although ironically a selfish gene may promote altruistic behaviors. According to Dawkins, the possibly disappointing answer to the question "what is the meaning of life?" may be "the survival and perpetuation of ribonucleic acids and their associated proteins". | + | |

| + | According to the [[modern evolutionary synthesis]], which integrated Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, Gregor Mendel's theory of genetics as the basis for biological inheritance, and mathematical population genetics, evolution consists primarily of changes in the frequencies of alleles between one generation and another as a result of [[natural selection]]. Natural selection has traditionally been viewed as acting on individual organisms, but has also been seen as working on groups of organisms. The ''gene-centered view of evolution'', however, sees natural selection as working on the level of genes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Gene-centered view of evolution=== | ||

| + | The gene-centered view of evolution, gene selection theory, or selfish gene theory holds that [[natural selection]] acts through differential survival of competing genes, increasing the frequency of those alleles whose phenotypic effects successfully promote their own propagation. According to this theory, adaptations are the phenotypic effects through which genes achieve their propagation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The view of the gene as the unit of selection was mainly developed in the books ''Adaptation and Natural Selection'', by George C. Williams, and also in ''The Selfish Gene'' and ''The Extended Phenotype'', both by Richard Dawkins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Essentially, this view notes that the genes that exist today are those that have reproduced successfully in the past. Often, many individual organisms share a gene; thus, the death of an individual need not mean the extinction of the gene. Indeed, if the sacrifice of one individual enhances the survivability of other individuals with the same gene, the death of an individual may enhance the overall survival of the gene. This is the basis of the selfish gene view, popularized by Richard Dawkins. He points out in his book, ''The Selfish Gene'', that to be successful genes need have no other "purpose" than to propagate themselves, even at the expense of their host organism's welfare. A human that behaved in such a way would be described as "selfish," although ironically a selfish gene may promote altruistic behaviors. According to Dawkins, the possibly disappointing answer to the question "what is the meaning of life?" may be "the survival and perpetuation of ribonucleic acids and their associated proteins." | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, a number of prominent evolutionists, including Ernst Mayr and Stephen Jay Gould strongly reject the selfish gene theory. Mayr states: " | ||

==Chemistry and function of genes== | ==Chemistry and function of genes== | ||

| Line 143: | Line 152: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | Curtis, H, Barnes, N. S., 1989, Biology, Fifth Edition, Worth Publishers Inc., New York, | ||

| + | |||

Dawkins, Richard (1990). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192860925. [[http://print.google.com/print?id=WkHO9HI7koEC]] | Dawkins, Richard (1990). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192860925. [[http://print.google.com/print?id=WkHO9HI7koEC]] | ||

| Line 151: | Line 162: | ||

*[[RNA]] | *[[RNA]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{credit2|Gene|56592587|Gene-centered_view_of_evolution|66242281}} |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

Revision as of 18:42, 28 July 2006

Genes are the units of heredity in living organisms. They are encoded in the organism's genetic material—DNA or RNA—and control the physical aspects of the organism. During reproduction, the genetic material is passed on from the parent(s) to the offspring. Genetic material can also be passed between un-related individuals (e.g. via transfection, or on viruses). Genes encode the information necessary to construct the chemicals (proteins, etc.) needed for the organism to function.

The word "gene" was coined in 1909 by Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen for the fundamental physical and functional unit of heredity. The word gene was derived from Hugo De Vries' term pangen, itself a derivative of the word pangenesis, which Darwin (1868) had coined. The word pangenesis is made from the Greek words pan (a prefix meaning "whole", "encompassing") and genesis ("birth") or genos ("origin").

The term "gene" is shared by many disciplines, including classical genetics, molecular genetics, evolutionary biology, and population genetics. Because each discipline models the biology of life differently, the usage of the word gene varies between disciplines. It may refer to either material or conceptual entities.

Following the discovery that DNA is the genetic material, and with the growth of biotechnology and the project to sequence the human genome, the common usage of the word "gene" has increasingly reflected its meaning in molecular biology, namely the segments of DNA thatcells transcribe into RNA and translate, at least in part, into proteins. The Sequence Ontology project defines a gene as: "A locatable region of genomic sequence, corresponding to a unit of inheritance, which is associated with regulatory regions, transcribed regions and/or other functional sequence regions."

In common speech, "gene" is often used to refer to the hereditary cause of a trait, disease, or condition—as in "the gene for obesity." Speaking more precisely, a biologist might refer to an allele or a mutation that has been implicated in or is associated with obesity. This is because biologists know that many factors other than genes decide whether a person is obese or not: eating habits, exercise, prenatal environment, upbringing, culture, and the availability of food, for example.

Moreover, it is very unlikely that variations within a single gene, or single genetic locus,fully determine one's genetic predisposition for obesity. These aspects of inheritance —the interplay between genes and environment, the influence of many genes—appear to be the norm with regard to many and perhaps most ("complex" or "multi-factoral") traits. The term phenotype refers to the characteristics that result from this interplay.

Overview

In molecular biology, a gene is considered to be the region of DNA (or RNA, in the case of some viruses) that determines the structure of a protein (the coding sequence), together with the region of DNA that controls when and where the protein will be produced (the regulatory sequence). The genetic code determines how the coding DNA sequence is converted into a protein sequence (via transcription and translation). The genetic code is essentially the same for all known life, from bacteria to humans.

Through the proteins they encode, genes govern the cells in which they reside. In multicellular organisms, much of the development of the individual is tied to genes, as well as the day-to-day functions of the cells. The instrumental roles of their protein products range from mechanical support of the cell structure to the transportation and manufacture of other molecules, and to the regulation of other proteins' activities.

Types of genes

Due to rare, spontaneous errors (e.g. in DNA replication) mutations in the sequence of a gene may arise. If these mutations occur in the germ line cells, they may be passed on to the organism's offspring. Once propagated to the next generation, this mutation may lead to variations within a species' population. Variants of a single gene are known as alleles, and differences in alleles may give rise to differences in traits, for example eye color. A gene's most common allele is called the wild type allele, and rare alleles are called mutants.

In most cases, RNA is an intermediate product in the process of manufacturing proteins from genes. However, for some gene sequences, the RNA molecules are the actual functional products. For example, RNAs known as ribozymes are capable of enzymatic function, and small interfering RNAs have a regulatory role. The DNA sequences from which such RNAs are transcribed are known as non-coding RNA, or RNA genes.

Most living organisms carry their genes and transmit them to offspring as DNA, but some viruses carry only RNA. Because they use RNA, their cellular hosts may synthesize their proteins as soon as they are infected and without the delay in waiting for transcription. On the other hand, RNA retroviruses, such as HIV, require the reverse transcription of their genome from RNA into DNA before their proteins can be synthesized.

Typical numbers of genes in an organism

| organism | genes | base pairs |

|---|---|---|

| Plant | <50,000 | <1011 |

| Human, mouse or rat | 25,000 | 3×109 |

| Fruit Fly | 13,767 | 1.3×108 |

| Honey bee | 15,000 | 3×108 |

| Worm | 19,000 | 9.7×107 |

| Fungus | 6,000 | 1.3×107 |

| Bacterium | 500–6,000 | 5×105–107 |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 500 | 580,000 |

| DNA virus | 10–900 | 5,000–800,000 |

| RNA virus | 1–25 | 1,000–23,000 |

| Viroid | 0–1 | ~500 |

The attached table gives typical numbers of genes and genome size for some organisms. Estimates of the number of genes in an organism are somewhat controversial because they depend on the discovery of genes, and no techniques currently exist to prove that a DNA sequence contains no gene. (In early genetics, genes could be identified only if there were mutations, or alleles.) Nonetheless, estimates are made based on current knowledge.

Human gene nomenclature

For each known human gene, the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) approves a gene name and symbol (short-form abbreviation). All approved symbols are stored in the HGNC Database. Each symbol is unique and each gene is only given one approved gene symbol. It is necessary to provide a unique symbol for each gene so that people can precisely communicate. This also facilitates electronic data retrieval from publications. In preference, each symbol maintains parallel construction in different members of a gene family and can be used in other species, such as the mouse.

History

The existence of genes was first suggested by Gregor Mendel, who, in the 1860s, studied inheritance in pea plants and hypothesized a factor that conveys traits from parent to offspring. Although he did not use the term gene, he explained his results in terms of inherited characteristics. Mendel was also the first to hypothesize independent assortment (the idea that pairs of alleles separate independently during meiosis), the distinction between dominant and recessive traits, the distinction between a heterozygote and homozygote (an organism with different or the same (respectively) alleles of a certain gene on homologous chromosomes), and the difference between what would later be described as genotype (specific genetic make-up) and phenotype (physical manifestation of the genetic make-up). Mendel's concept was finally named when Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene in 1909.

In the early 1900s, Mendel's work received renewed attention from scientists. In 1910, Thomas Hunt Morgan showed that genes reside on specific chromosomes. He later showed that genes occupy specific locations on the chromosome. With this knowledge, Morgan and his students began the first chromosomal map of the fruit fly Drosophila. In 1928, Frederick Griffith showed that genes could be transferred. In what is now known as Griffith's experiment, injections into a mouse of a deadly strain of bacteria that had been heat-killed transferred genetic information to a safe strain of the same bacteria, killing the mouse.

In 1941, George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum showed that mutations in genes caused errors in certain steps in metabolic pathways. This showed that specific genes code for specific proteins, leading to the "one gene, one enzyme" hypothesis. Oswald Avery, Collin Macleod, and Maclyn McCarty showed in 1944 that DNA holds the gene's information. In 1953, James D. Watson and Francis Crick demonstrated the molecular structure of DNA. Together, these discoveries established the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that proteins are translated from RNA which is transcribed from DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription in retroviruses.

Evolution and genes

Broadly defined, evolution is any heritable change in a population of organisms over time. Evolutionary changes are those that are inheritable via the genetic material. As noted by Curtis & Barnes (1989) "The changes in populations that are considered evolutionary are those that are inheritable via the genetic material from one generation to another." As such, evolution can also be defined in terms of allele frequency, with allele being alternative forms of a gene, such as an allele for blue eye color versus brown eye color.

Two important and popular evolutionary theories that address the pattern and process of evolution are the Theory of descent with modification and the theory of natural selection." The theory of descent with modification, or the "theory of common descent" deals with the pattern of evolution and essentially postulates that all organisms have descended from common ancestors by a continuous process of branching. The "theory of modification through natural selection," or the "theory of natural selection," deals with mechanisms and causal relationships, and offers one explanation for how evolution might have occurred— the process by which evolution took place to arrive at the pattern.

According to the modern evolutionary synthesis, which integrated Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, Gregor Mendel's theory of genetics as the basis for biological inheritance, and mathematical population genetics, evolution consists primarily of changes in the frequencies of alleles between one generation and another as a result of natural selection. Natural selection has traditionally been viewed as acting on individual organisms, but has also been seen as working on groups of organisms. The gene-centered view of evolution, however, sees natural selection as working on the level of genes.

Gene-centered view of evolution

The gene-centered view of evolution, gene selection theory, or selfish gene theory holds that natural selection acts through differential survival of competing genes, increasing the frequency of those alleles whose phenotypic effects successfully promote their own propagation. According to this theory, adaptations are the phenotypic effects through which genes achieve their propagation.

The view of the gene as the unit of selection was mainly developed in the books Adaptation and Natural Selection, by George C. Williams, and also in The Selfish Gene and The Extended Phenotype, both by Richard Dawkins.

Essentially, this view notes that the genes that exist today are those that have reproduced successfully in the past. Often, many individual organisms share a gene; thus, the death of an individual need not mean the extinction of the gene. Indeed, if the sacrifice of one individual enhances the survivability of other individuals with the same gene, the death of an individual may enhance the overall survival of the gene. This is the basis of the selfish gene view, popularized by Richard Dawkins. He points out in his book, The Selfish Gene, that to be successful genes need have no other "purpose" than to propagate themselves, even at the expense of their host organism's welfare. A human that behaved in such a way would be described as "selfish," although ironically a selfish gene may promote altruistic behaviors. According to Dawkins, the possibly disappointing answer to the question "what is the meaning of life?" may be "the survival and perpetuation of ribonucleic acids and their associated proteins."

However, a number of prominent evolutionists, including Ernst Mayr and Stephen Jay Gould strongly reject the selfish gene theory. Mayr states: "

Chemistry and function of genes

Chemical structure of a gene

Four kinds of sequentially linked nucleotides compose a DNA molecule or strand (more at DNA). These four nucleotides constitute the genetic alphabet. A sequence of three consecutive nucleotides, called a codon, is the protein-coding vocabulary. The sequence of codons in a gene specifies the amino-acid sequence of the protein it encodes.

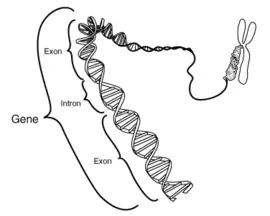

In most eukaryotic species, very little of the DNA in the genome encodes proteins, and the genes may be separated by vast sequences of so-called junk DNA. Moreover, the genes are often fragmented internally by non-coding sequences called introns, which can be many times longer than the coding sequence. Introns are removed on the heels of transcription by splicing. In the primary molecular sense, they represent parts of a gene, however.

All the genes and intervening DNA together make up the genome of an organism, which in many species is divided among several chromosomes and typically present in two or more copies. The location (or locus) of a gene and the chromosome on which it is situated is in a sense arbitrary. Genes that appear together on the chromosomes of one species, such as humans, may appear on separate chromosomes in another species, such as mice. Two genes positioned near one another on a chromosome may encode proteins that figure in the same cellular process or in completely unrelated processes. As an example of the former, many of the genes involved in spermatogenesis reside together on the Y chromosome.

Many species carry more than one copy of their genome within each of their somatic cells. These organisms are called diploid if they have two copies or polyploid if they have more than two copies. In such organisms, the copies are practically never identical. With respect to each gene, the copies that an individual possesses are liable to be distinct alleles, which may act synergistically or antagonistically to generate a trait or phenotype. The ways that gene copies interact are explained by chemical dominance relationships (more at allele).

Expression of molecular genes

For various reasons, the relationship between DNA strand and a phenotype trait is not direct. The same DNA strand in two different individuals may result in different traits because of the effect of other DNA strands or the environment.

- The DNA strand is expressed into a trait only if it is transcribed to RNA. Because the transcription starts from a specific base-pair sequence (a promoter) and stops at another (a terminator), our DNA strand needs to be correctly placed between the two. If not, it is considered as junk DNA, and is not expressed.

- Cells regulate the activity of genes in part by increasing or decreasing their rate of transcription. Over the short term, this regulation occurs through the binding or unbinding of proteins, known as transcription factors, to specific non-coding DNA sequences called regulatory elements. Therefore, to be expressed, our DNA strand needs to be properly regulated by other DNA strands.

- The DNA strand may also be silenced through DNA methylation or by chemical changes to the protein components of chromosomes (see histone).

- The RNA is often edited before its translation into a protein. Eukaryotic cells splice the transcripts of a gene, by keeping the exons and removing the introns. Therefore, the DNA strand needs to be in an exon to be expressed. Because of the complexity of the splicing process, one transcribed RNA may be spliced in alternate ways to produce not one but a variety of proteins (alternative splicing) from one pre-mRNA (mRNA transcript at pre-splicing stage). Prokaryotes produce a similar effect by shifting reading frames (the three ways the mRNA can be read by grouping the nucleotides into sets of three, as codons) during translation.

- The translation of RNA into a protein also starts with a specific start and stop sequence.

- Once produced, the protein interacts with the many other proteins in the cell, according to the cell metabolism. This interaction finally produces the trait.

This complex process helps explain the different meanings of "gene":

- a nucleotide sequence in a DNA strand;

- or the transcribed RNA, prior to splicing;

- or the transcribed RNA after splicing, i.e. without the introns

The latter meaning of gene is the result of more "material entity" than the first one.

Mutations and evolution

Just as there are many factors influencing the expression of a particular DNA strand, there are many ways to have genetic mutations.

For example, natural variations within regulatory sequences appear to underlie many of the heritable characteristics seen in organisms. The influence of such variations on the trajectory of evolution through natural selection may be as large as or larger than variation in sequences that encode proteins. Thus, though regulatory elements are often distinguished from genes in molecular biology, in effect they satisfy the shared and historical sense of the word. Indeed, a breeder or geneticist, in following the inheritance pattern of a trait, has no immediate way to know whether this pattern arises from coding sequences or regulatory sequences. Typically, he or she will simply attribute it to variations within a gene.

Errors during DNA replication may lead to the duplication of a gene, which may diverge over time. Though the two sequences may remain the same, or be only slightly altered, they are typically regarded as separate genes (i.e. not as alleles of the same gene). The same is true when duplicate sequences appear in different species. Yet, though the alleles of a gene differ in sequence, nevertheless they are regarded as a single gene (occupying a single locus).

Richard Dawkins' The Selfish Gene and The Extended Phenotype defended the idea that the gene is the only replicator in living systems. This means that only genes transmit their structure largely intact and are potentially immortal in the form of copies. So, genes should be the unit of selection.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Curtis, H, Barnes, N. S., 1989, Biology, Fifth Edition, Worth Publishers Inc., New York,

Dawkins, Richard (1990). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192860925. [[1]]

Williams, G.C. 1966. Adaptation and Natural Selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

See also

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.